Overview

An acoustic neuroma is a benign Schwann-cell derived tumour, which commonly arises from the eight cranial nerve.

An acoustic neuroma, also known as a vestibular schwannoma, is a benign intracranial tumour that is derived from Schwann cells that are one of the major supporting nerve cells in the peripheral nervous system.

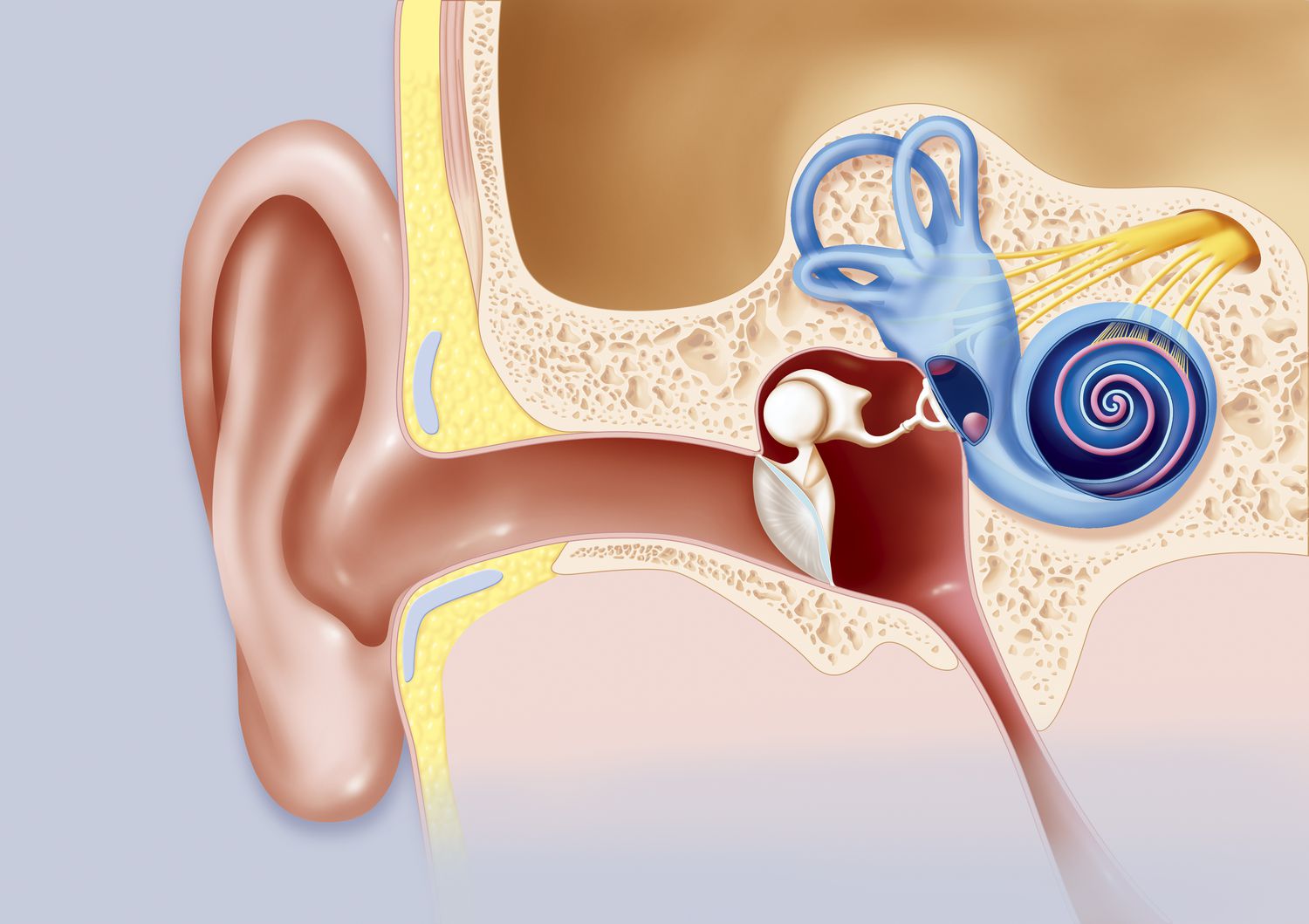

It is typically a slow growing tumour that arises from the eighth cranial nerve supplying the inner ear. This cranial nerve, also known as the vestibulocochlear nerve, has important functions in both hearing and balance. An acoustic neuroma is typically unilateral and leads to unilateral sensorineural hearing loss (bilateral may suggest an underlying genetic disorder).

Epidemiology

Acoustic neuromas account for approximately 8% of all intra-cranial tumours.

The median age of diagnosis of an acoustic neuromas is 50 years old and they are unilateral in >90% of cases. There is no major sex predominance, and the incidence is around 1 in 100,000 person-years.

Aetiology & pathophysiology

An acoustic neuroma is typically a slow-growing tumour that usually arises from branches of the vestibular nerve.

Acoustic neuromas usually occur sporadically from Schwann cells of the vestibular branch of the eighth cranial nerve. The actual cause of the tumour development is unknown but several risk factors have been suggested such as exposure low-dose radiation in childhood, cell phone use, and noise exposure. However, the data is conflicting.

Patients with an underlying genetic predisposition (e.g. variant in the NF2 gene) are at increased risk of developing acoustic neuromas and discussed in more detail below on neurofibromatosis. Malignant transformation of an acoustic neuroma is very rare.

Cerebellopontine angle (CPA)

The cerebellopontine angle (CPA) is located between the cerebellum and the pons of the brainstem. It is a triangular space in the posterior cranial fossa that contains the CPA cistern. A cistern (i.e. a reservoir) is essentially an opening of the subarachnoid space that is filled with cerebrospinal fluid. There are several cisterns within the central nervous system and these openings allow the passage of important structures (e.g. nerves and vessels).

The CPA cistern contains several key structures:

- Nerves: cranial nerves V, VI, VII and VIII

- Artery: anteroinferior cerebellar artery (AICA)

- Vein: petrosal vein

The CPA is important anatomically because it is may be the site of an intracranial tumour. In fact, up to 90% of tumours at the CPA are due to an acoustic neuroma. Other pathologies that can occur in this area include meningiomas, vascular malformations, epidermoid tumours, or even primary schwannomas of other cranial nerves (e.g. facial).

Due to the close association of the CPA with the vestibulocochlear nerve, patients with an acoustic neuroma are at risk of developing hearing loss, tinnitus, dizziness, vertigo, headaches, and gait dysfunction.

Neurofibromatosis

Neurofibromatosis (NF) is a genetic condition, which is divided into three main types based on the underlying genetic variant.

- Neurofibromatosis type 1 (autosomal dominant): variant in NF1 gene

- NF2-related schwannomatosis (autosomal dominant): variant in NF2 gene

- Schwannomatoses related to genetic variants other than NF2 (e.g. SMARCB1)

NF2-related schwannomatosis was formally known as neurofibromatosis type 2. However, the terminology changed to reflect that it is part of a spectrum of conditions that predispose to the formation of schwannomas with significant clinical overlap. The NF2 gene encodes the protein merlin, which acts as a tumour suppressor gene.

One of the hallmarks of this condition is the formation of bilateral vestibular schwannomas that develop in 90-95% of patients by the age of 30 years old. This can lead to early onset tinnitus, hearing loss, and balance dysfunction. The condition is associated with many other clinical features that are not explored further here.

Clinical features

The characteristic feature of an acoustic neuroma is unilateral sensorineural hearing loss.

Patients with an acoustic neuroma may present with a myriad of clinical features depending on the size of the lesion and how it impacts on the surrounding cranial nerves and cerebellum.

Symptoms

- Hearing loss (typically asymmetrical sensorineural): seen in up to 95% of patients (only two thirds may be aware of the limitation)

- Tinnitus

- Unsteadiness

- Facial numbness (involvement of V cranial nerve)

- Facial weakness (involvement of VII cranial nerve)

- Dry eyes/mouth or paroxysmal lacrimation (involvement of VII cranial nerve)

- Dysarthria/dysphagia (involvement of lower cranial nerves due to large tumours)

Signs

Overt neurological signs are usually only seen as late features in patients with a large acoustic neuroma.

- Cerebellar signs: nystagmus, ataxia

- Papilloedema: due to raised intracranial pressure

Features of NF2-related schwannomatosis

NF2-related schwannomatosis is characterised by the development of multiple neurological lesions including schwannomas (not just of the vestibulocochlear nerve), meningiomas, and spinal tumours. It can also lead to characteristic visual and cutaneous lesions. Key features that support this diagnosis include bilateral sensorineural hearing loss, early age of onset, and the following clinical features:

- Pigmented plaque-like cutaneous lesions

- Subcutaneous nodules

- Cataracts

- Peripheral neuropathy

- Seizures

Diagnosis & investigations

The principal investigations for an acoustic neuroma are audiometry and MRI imaging of the brain.

The diagnosis of acoustic neuroma is typically made by the presence of new-onset unilateral hearing loss. Patients are then referred for formal hearing testing that confirms sensorineural hearing loss, which leads to MRI imaging of the brain to look for a specific cause (i.e. acoustic neuroma). Alternatively, patients may present with a constellation of symptoms suggestive of a CPA tumour leading to urgent imaging of the brain.

Imaging

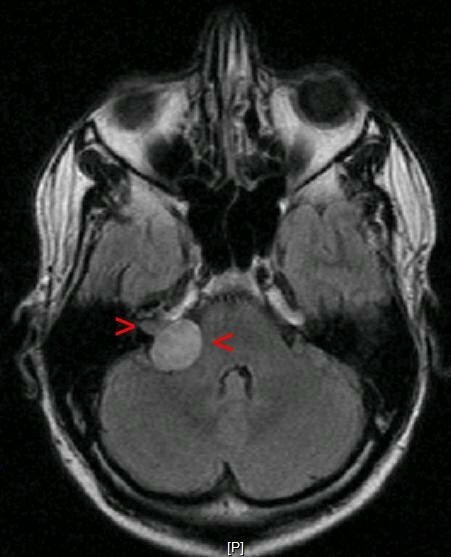

MRI is the most sensitive modality for the diagnosis of acoustic neuroma, which can detect tumours as small as 1-2 mm in size. In those who cannot tolerate an MRI, CT with and without contrast can be used but this is less sensitive at detecting small lesions.

Right-sided acoustic neuroma (right arrow heads) on MRI

Audiometry

Audiometry can be used to confirm the diagnosis of hearing loss. This type of assessment involves a detailed evaluation of a patient’s hearing ability. Audiometry may involves several discrete assessments including:

- Audiogram (i.e. pure tone testing): assesses the ability to detect pure tone stimuli at different frequencies. This is completed with both air conduction (via headphones) and bone conduction (via an oscillator). Testing both types of conduction helps to determine the aetiology of hearing loss

- Speech audiometry: assesses your ability to hear and comprehend spoken words. It is divided into two parts known as speech reception threshold (i.e. the softest level at which 50% of two-syllable words can be repeated) and word discrimination score (i.e. the percentage of specific words that can be repeated at different sensation levels)

- Tympanometry: assesses the middle ear in response to changes in air pressure. Essentially, it measures how the eardrum moves to draw conclusions on how the middle ear system is working

Management

Acoustic neuromas may be treated with surgery or radiotherapy.

Acoustic neuromas are generally slow-growing tumours. Therefore, the choice of treatment depends on multiple factors such as the size of the tumour, patient co-morbidities, clinical features, and overall patient preference. The three options for patients include:

- Surgery

- Radiotherapy

- Close observation

Koos classification

The Koos classification is used to grade acoustic neuromas as I-IV based on its size and location. Alongside a patients’ clinical features this helps in the decision making process. For example, large grade IV tumours usually require surgery, whereas smaller grade I-II tumours may be observed or referred for stereotactic radiosurgery.

Surgery

A variety of surgical techniques can be used and typically performed by both a neurosurgeon and ENT surgeon. The choice of technique depends on the size of the tumour and need for preservation of hearing function. Options can include:

- Suboccipital retrosigmoid (retromastoid) approach: typically performed by neurosurgeon

- Translabyrinthine approach: typically performed by ENT surgeon

- Middle fossa approach: particularly useful for preserving hearing function

Complete resection is achievable in most patients with a low recurrence rate. However, curative resection may be more difficult when there is an attempt to preserve anatomical structures. Up to 20% of patients may have recurrence if the initial resection is incomplete. Important complications associated with surgery including hearing loss, facial weakness, vestibular disturbance (i.e. balance issues), persistent headaches, bleeding, infection and cerebrospinal fluid leaks.

Radiotherapy

A variety of different radiotherapy techniques have been used to treat acoustic neuromas including stereotactic radiosurgery, stereotactic radiotherapy, or conventional radiotherapy. Stereotactic radiotherapy and radiosurgery are highly specialised forms of radiotherapy that precisely target the tumour. Radiosurgery is carried out in a single day, whereas radiotherapy requires frequent clinic visits and treatment over several weeks. Radiotherapy is more appropriate for smaller tumours (i.e. < 3 cm) or among patients who are not suitable for surgery.

Close observation

Instead of offering treatment, some acoustic neuromas may be closely monitored by serial imaging. Generally, MRI may be offered at 6-12 months intervals. Observation is a good option in small, asymptomatic acoustic neuromas. The aim of observation is to monitor for tumour growth and hearing function. In those with complete hearing loss, observation may be a valid option since other forms of treatment are associated with a small, but significant risk of facial nerve damage.

Complications

Progressive enlargement of an acoustic neuroma may lead to damage and compression of surrounding structures.

The complications of acoustic neuromas generally depend on the size of the tumour and the nerves that are involved. These may include cranial nerve palsies (e.g. facial, vestibulocochlear), hydrocephalus, and cerebellar dysfunction.

Serious complications may also arise from treatment of acoustic neuromas with radiotherapy or surgery. These can include:

- Bleeding

- Infection

- Facial nerve damage

- Hearing loss

- Cerebrospinal fluid leak (surgery)

- Secondary malignancy (radiotherapy)

- Hydrocephalus (radiotherapy)

- Headaches