What is a brain tumour?

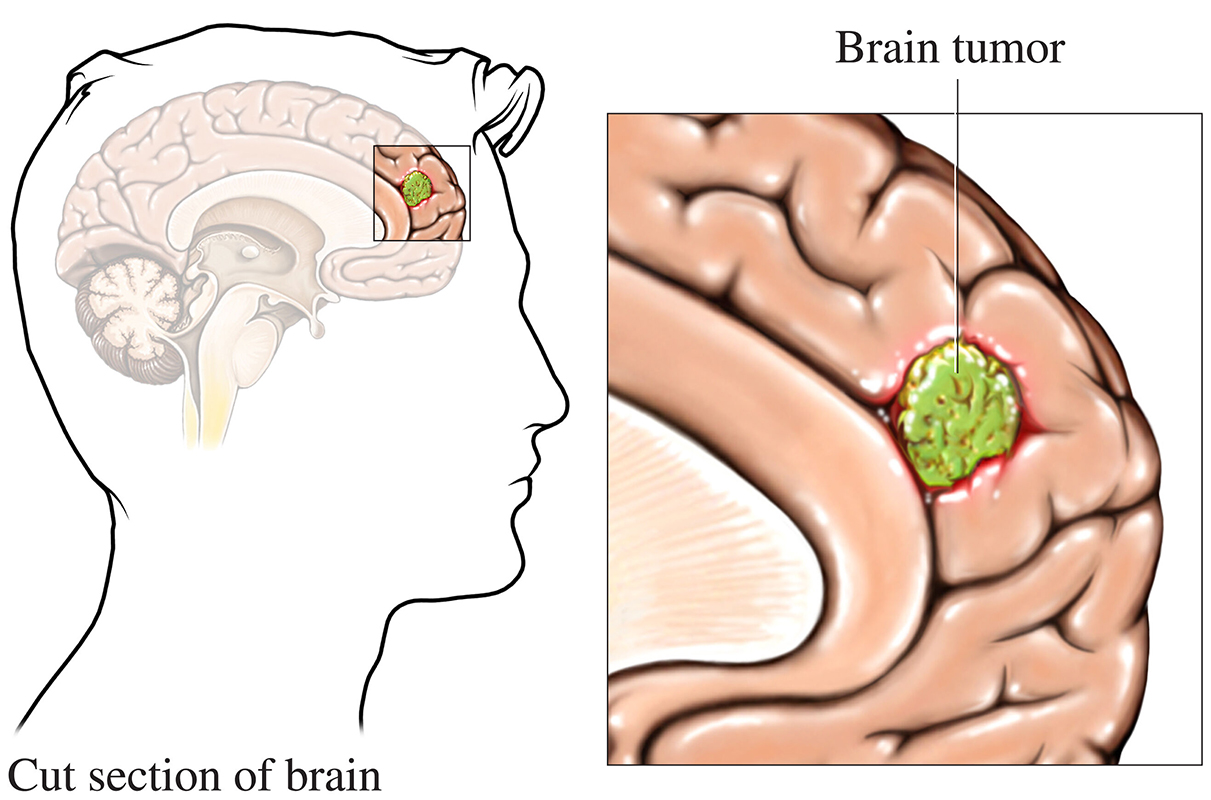

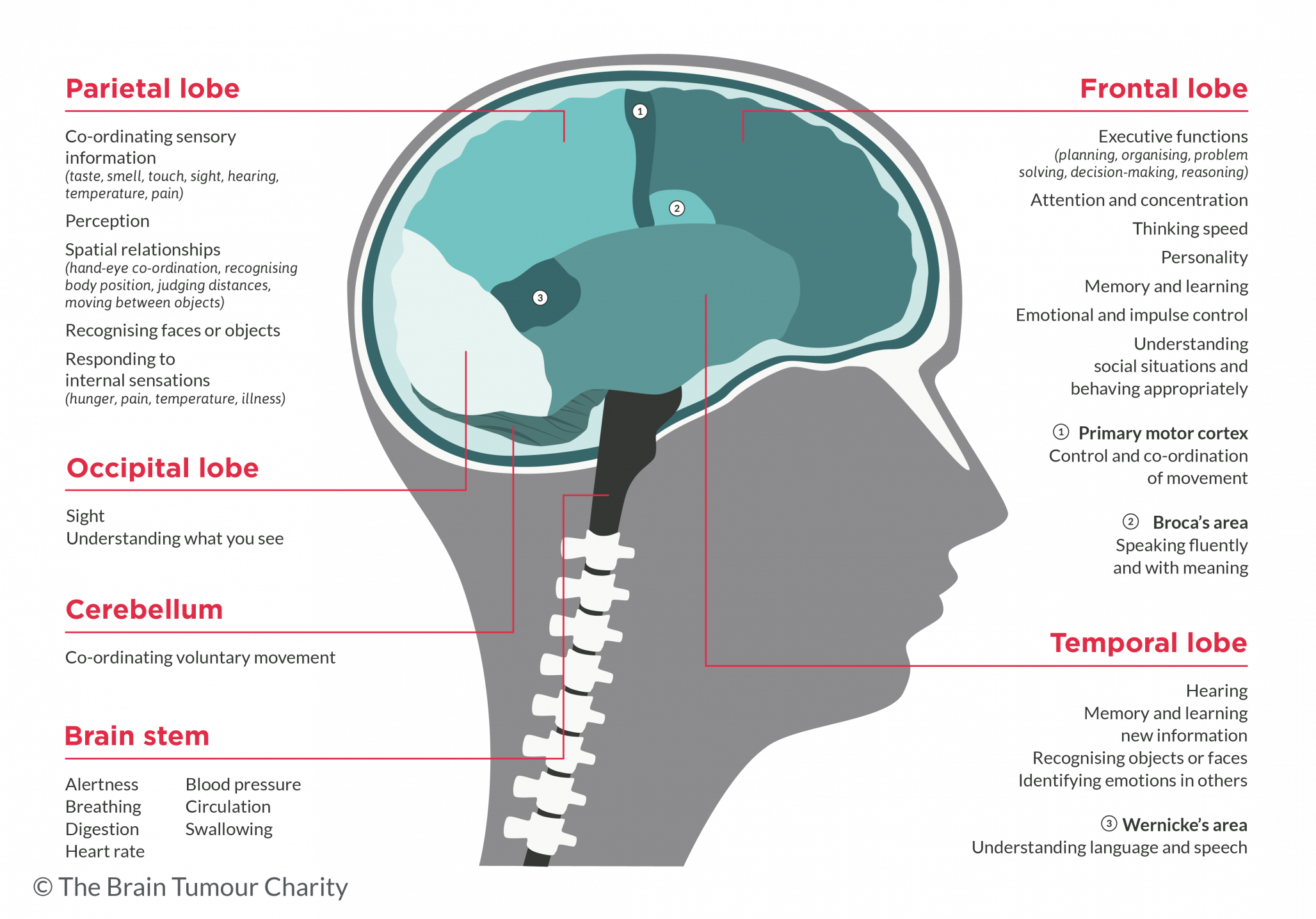

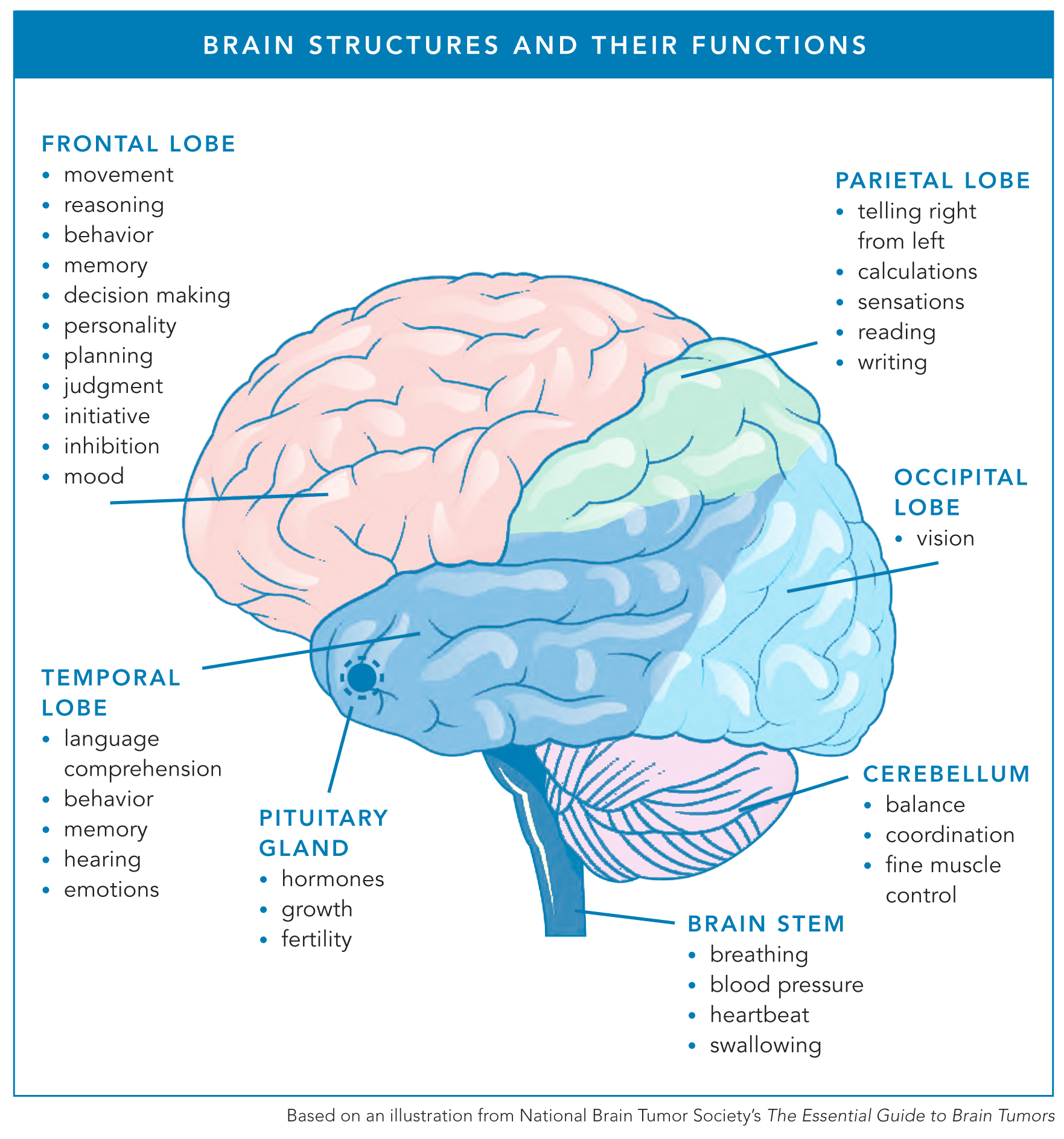

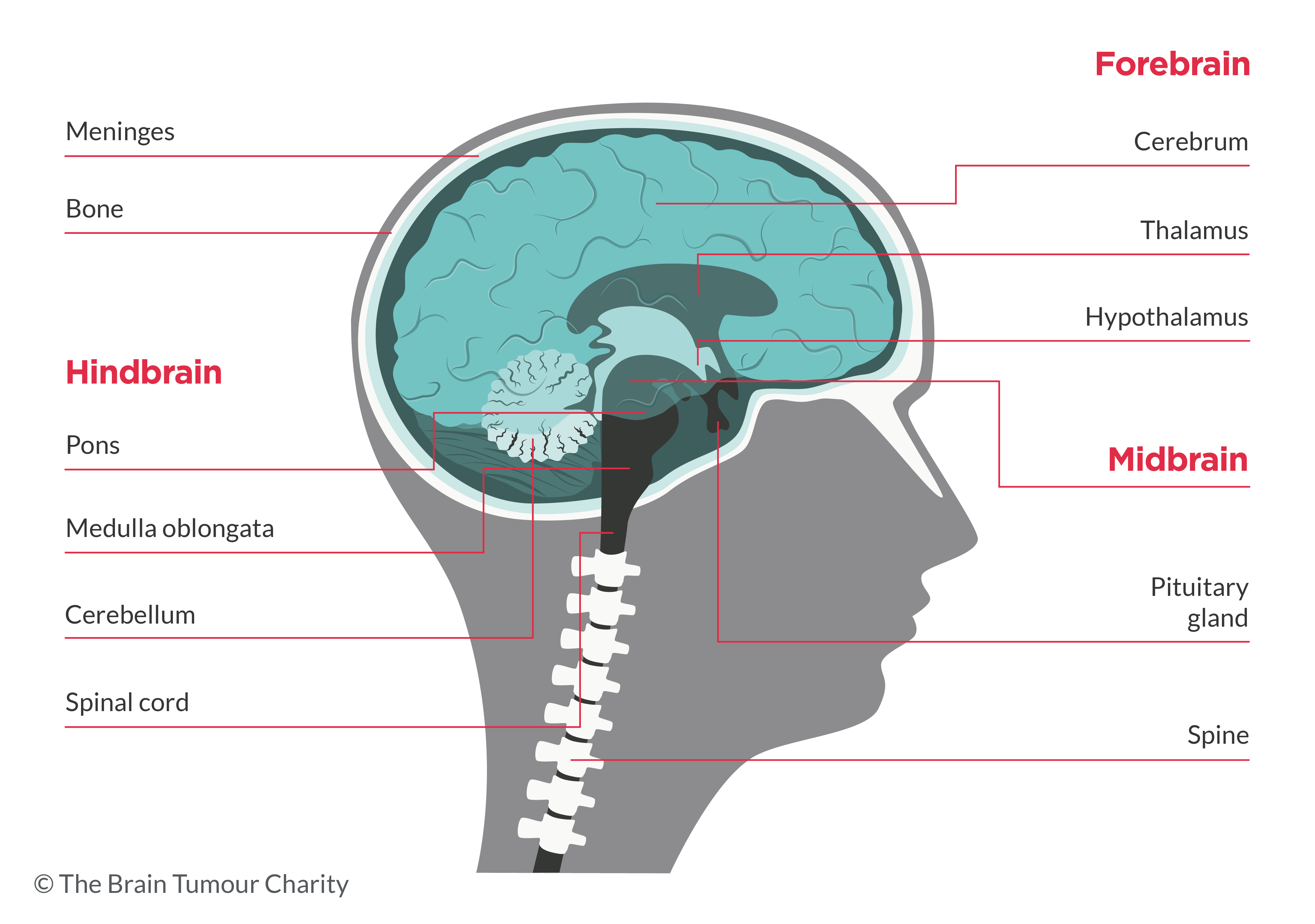

A brain tumour is a lump of abnormal cells growing in your brain. Your brain controls all the parts of your body and its functions and produces your thoughts. Depending on where it is, a tumour in your brain can affect these functions.

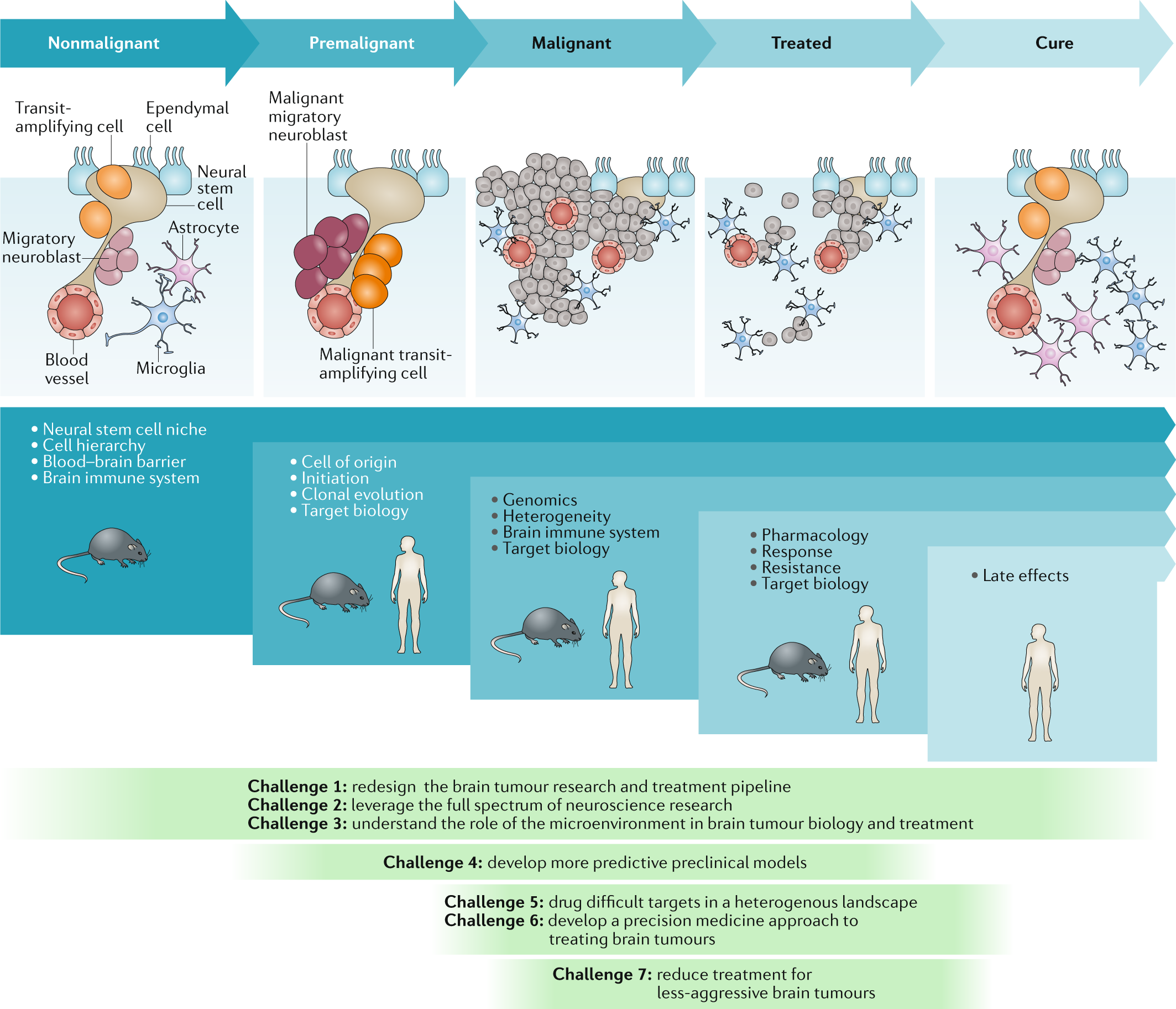

When cells grow abnormally they may form a lump called a tumour. Tumours can be benign or malignant.

A benign tumour grows slowly and stays in one place. It is unlikely to spread to another part of your body.

Benign tumours are not cancerous. But a benign brain tumour may cause damage just by being there and pressing on your brain or nearby structures. This can be life-threatening, or affect other parts of your body, and may need urgent treatment.

A malignant tumour is cancerous. It can spread to other areas of your brain, or your body. It can also be called brain cancer.

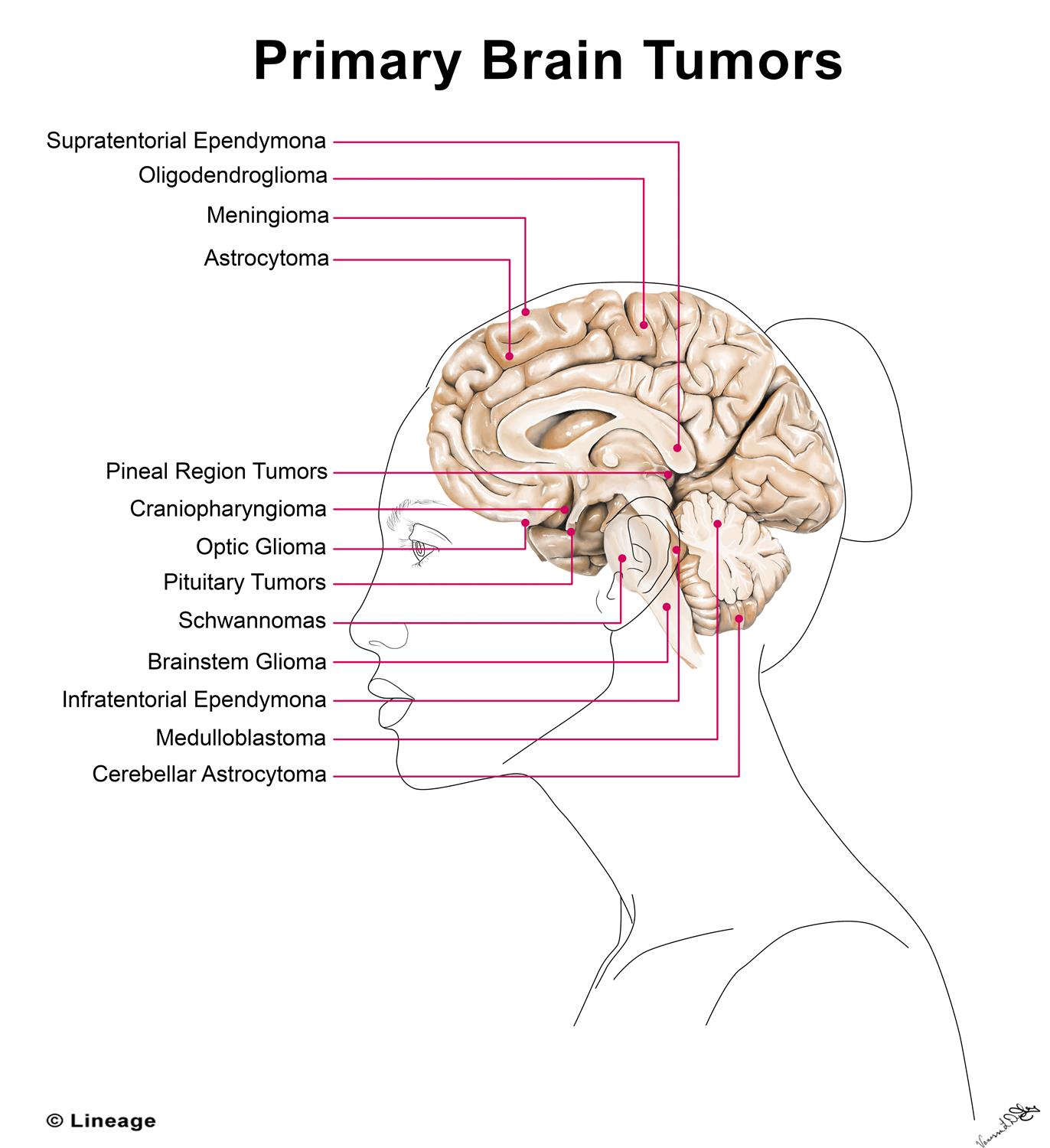

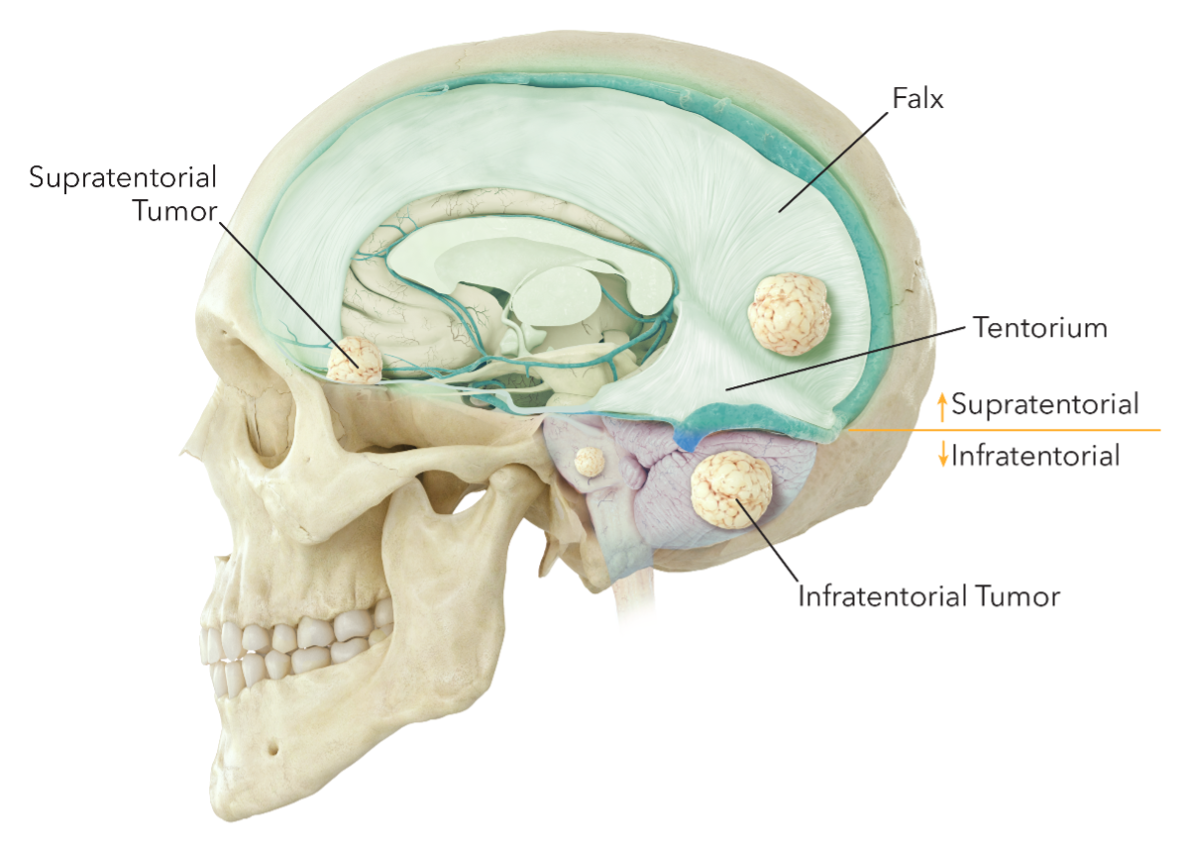

Types of brain tumours

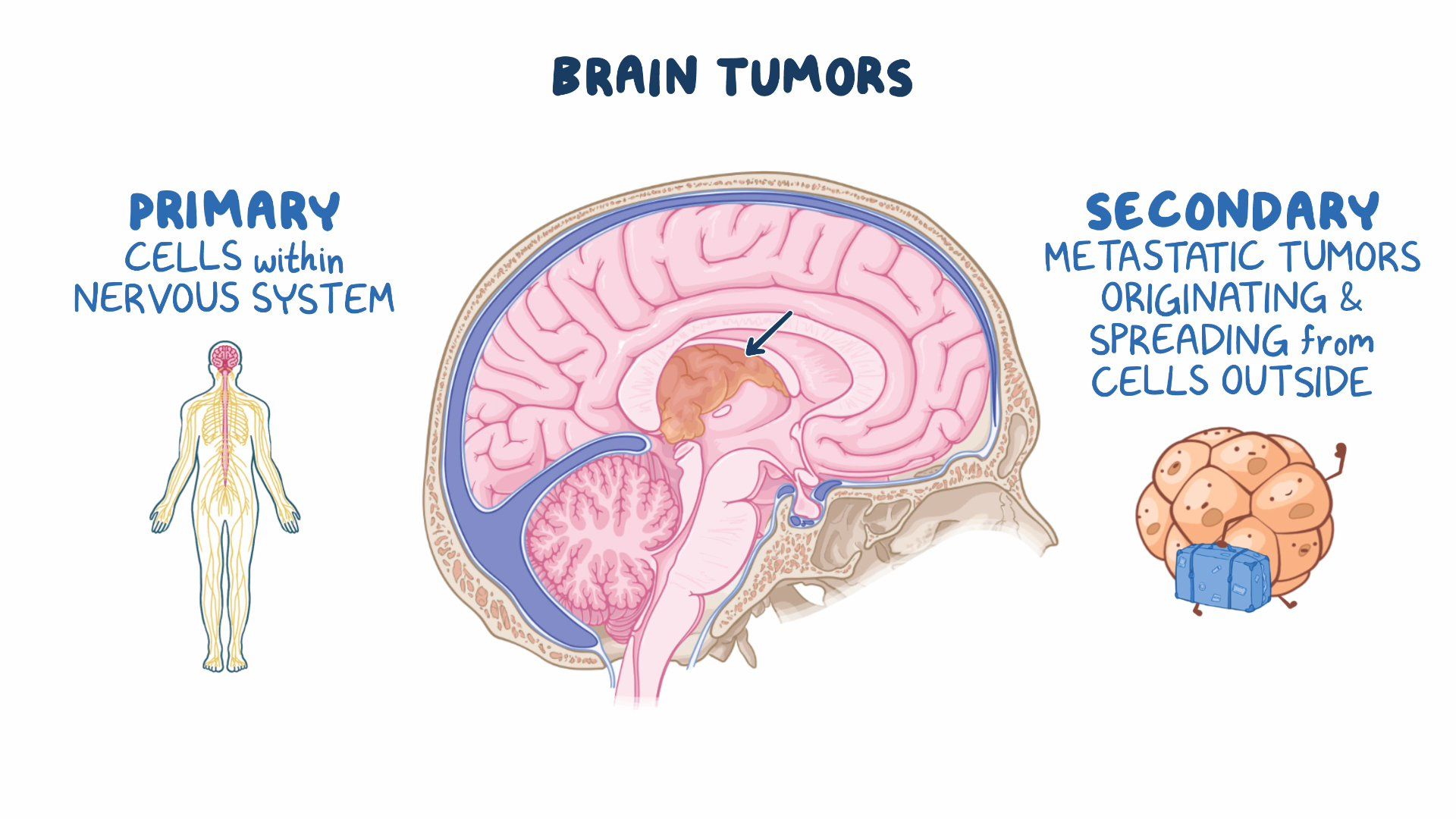

Brain tumours can either be ‘primary’ or ‘secondary’.

- A primary brain tumour is a tumour that has started in the brain.

- A secondary brain tumour is a cancer from elsewhere in the body that has spread or ‘metastasised’ to the brain.

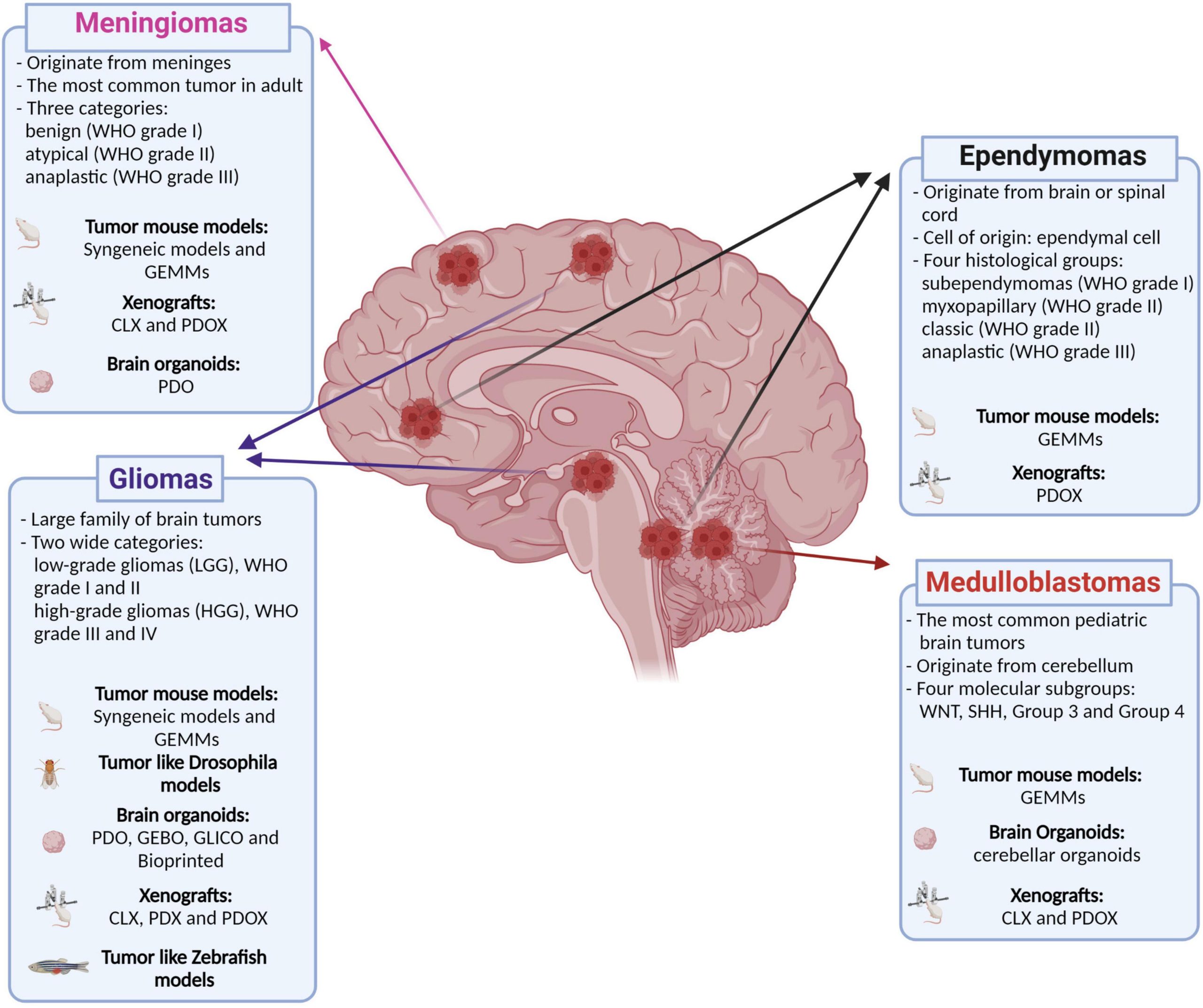

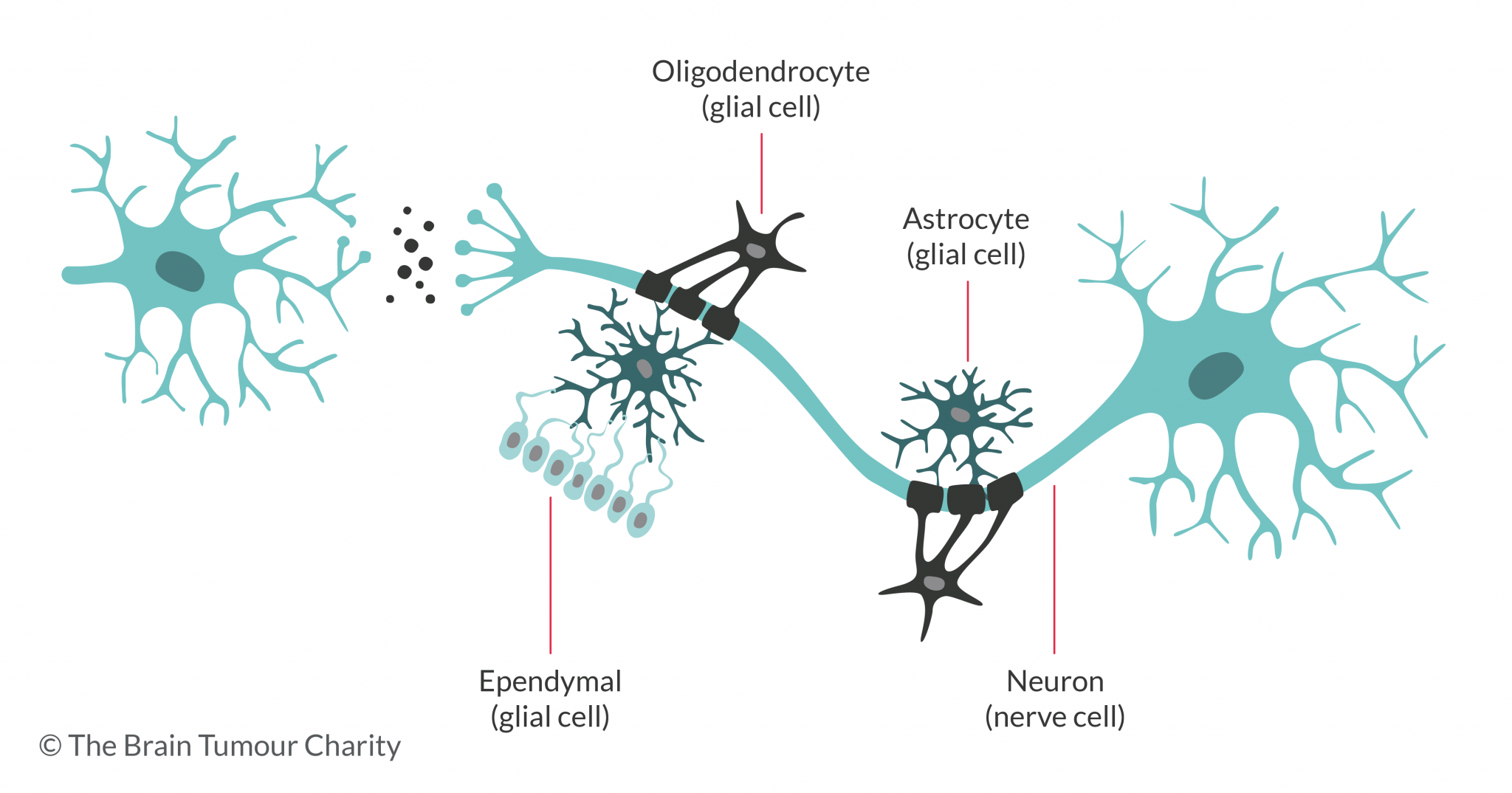

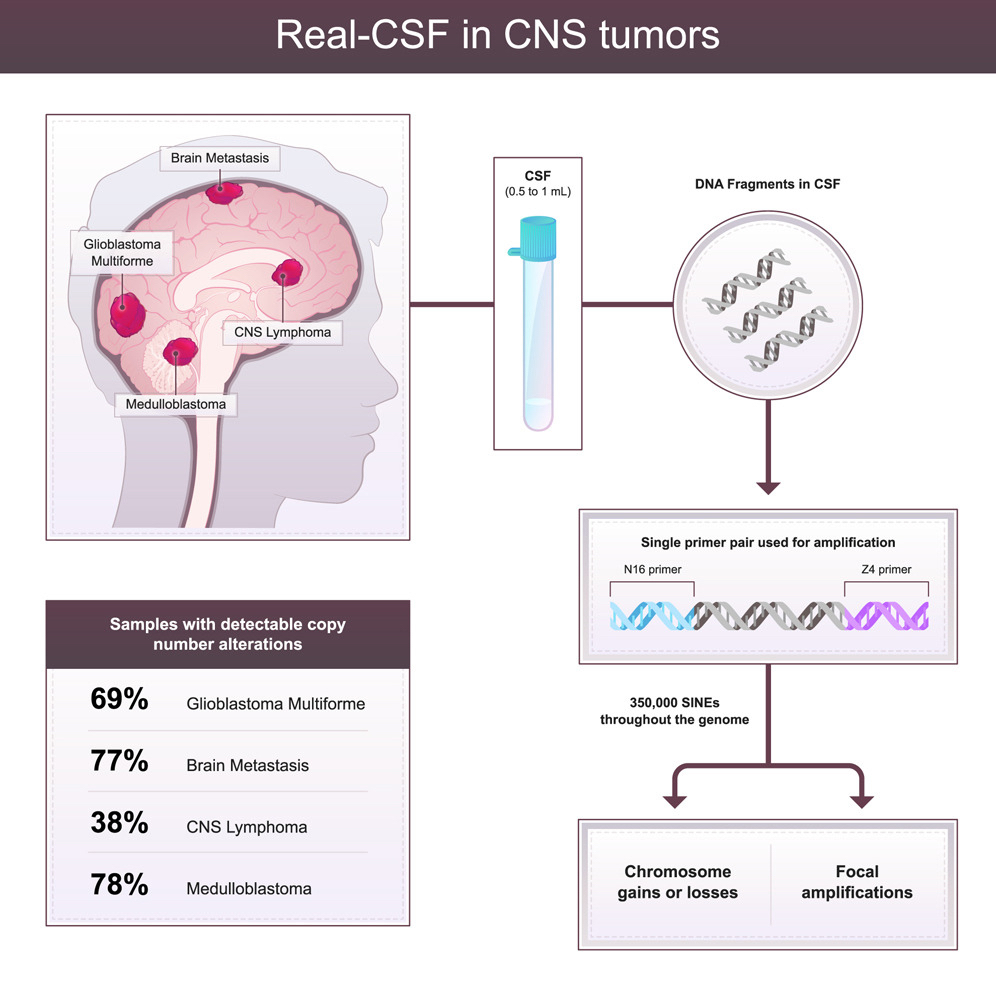

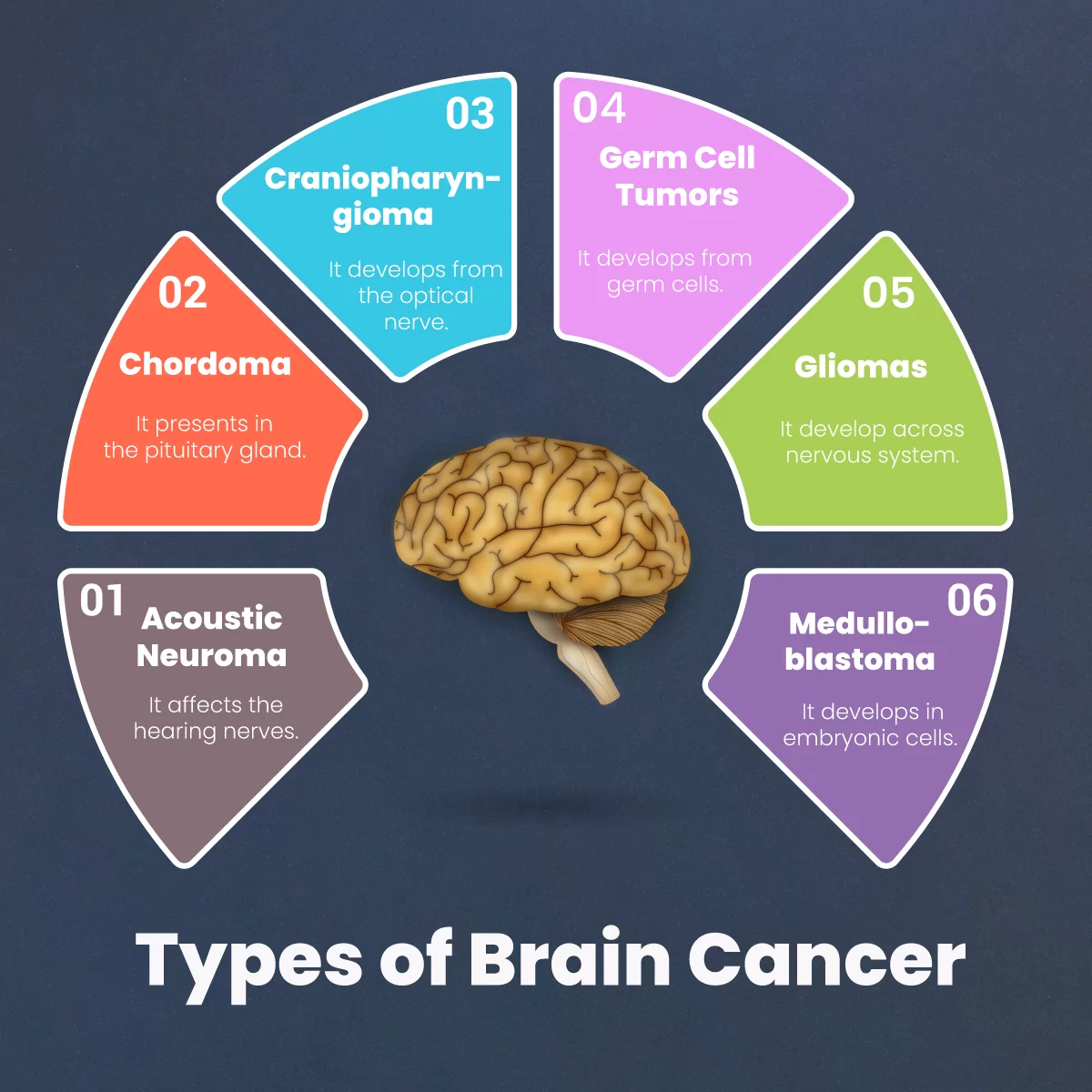

There are many types of brain tumours. Together with tumours of the spinal cord, they are collectively called central nervous system (CNS) tumours.

Primary brain tumours

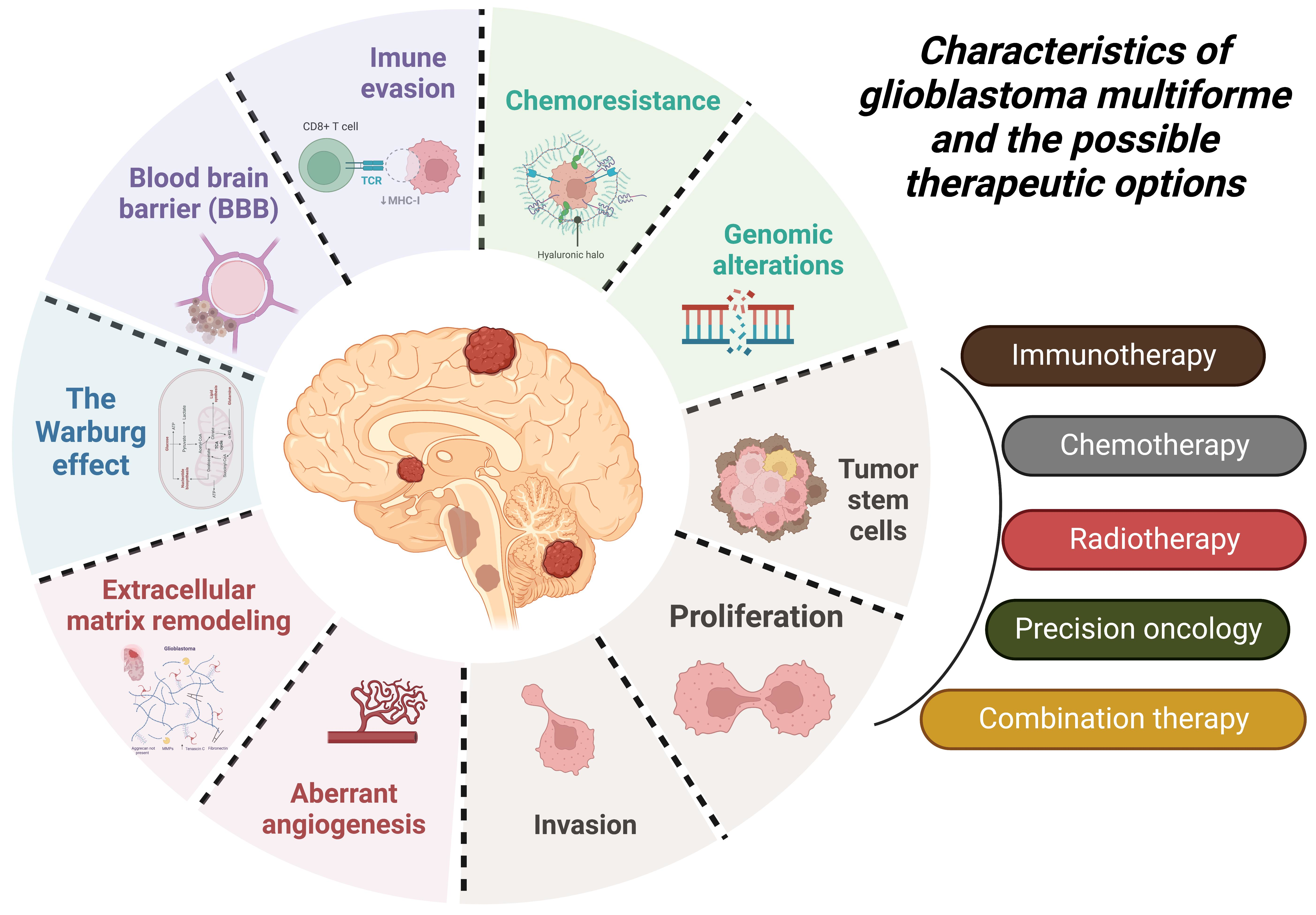

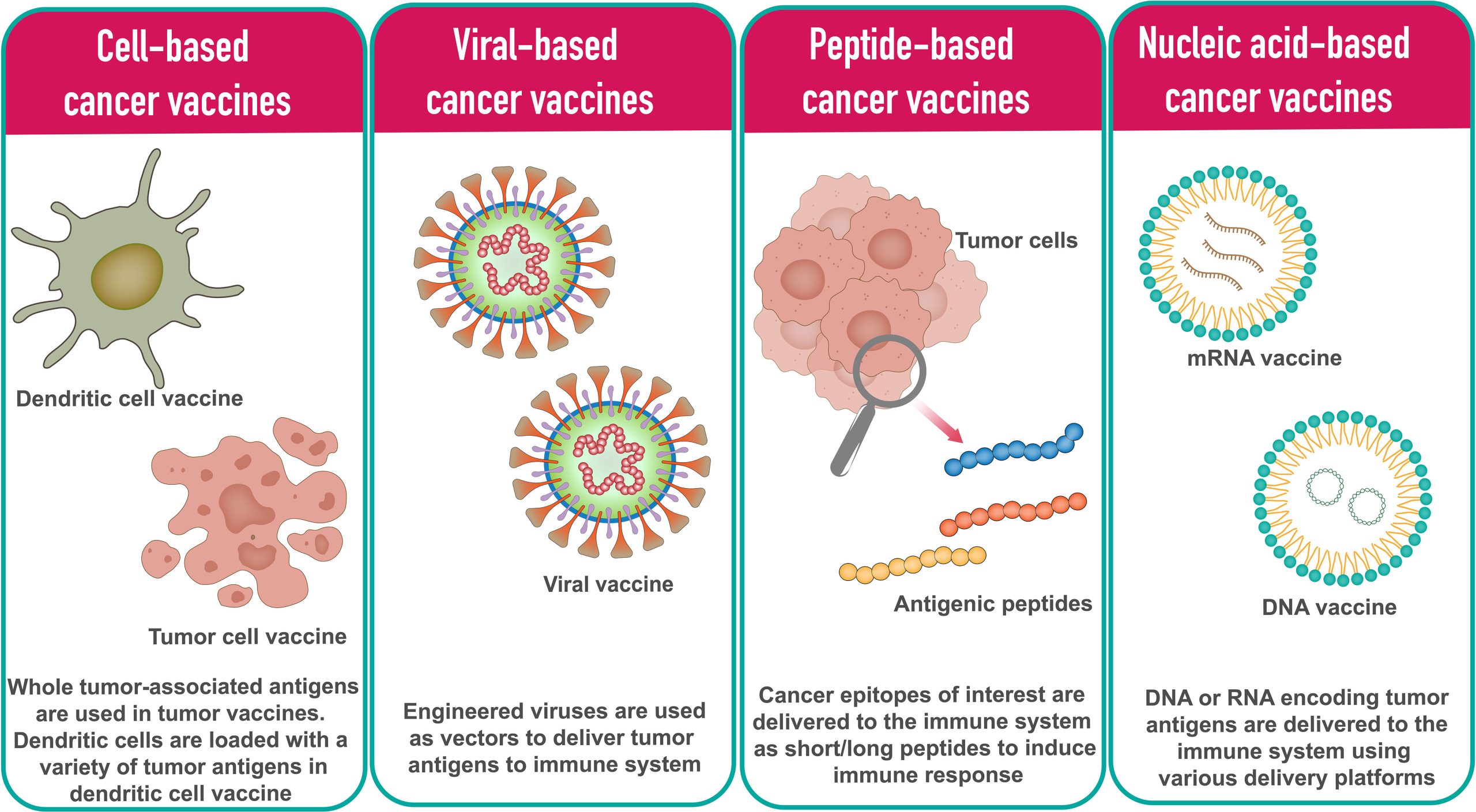

Brain tumours are usually named according to the type of cell they started in. Some common types of primary brain tumours are gliomas (including astrocytomas and glioblastomas) — which start in glial cells, meningiomas — which start in the meninges, and medulloblastomas — which start in the cerebellum.

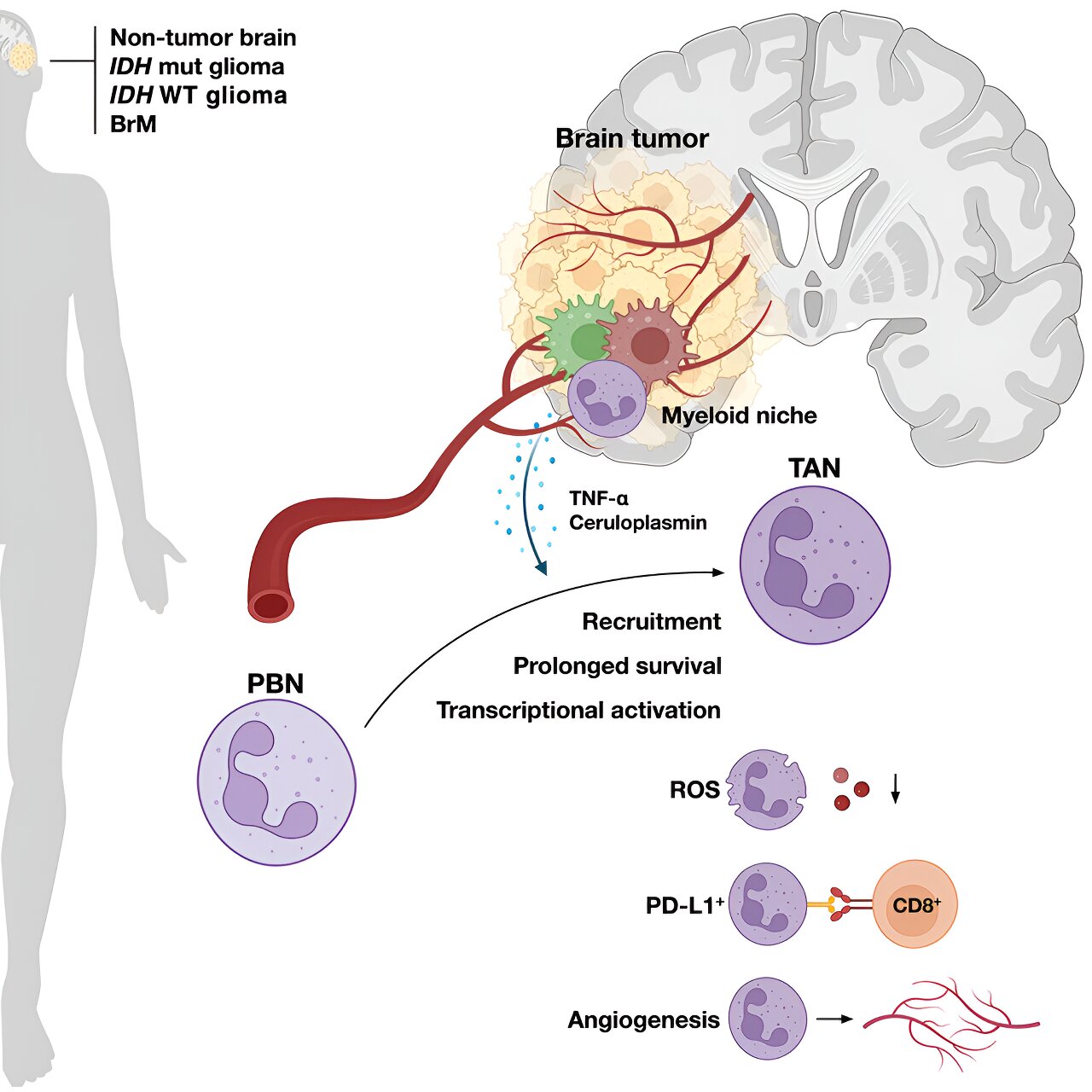

Secondary brain tumours

Most types of cancer can spread to the brain, forming a secondary brain tumour. The types of cancer that most commonly spread to the brain include melanoma, bowel, breast, kidney and lung cancers.

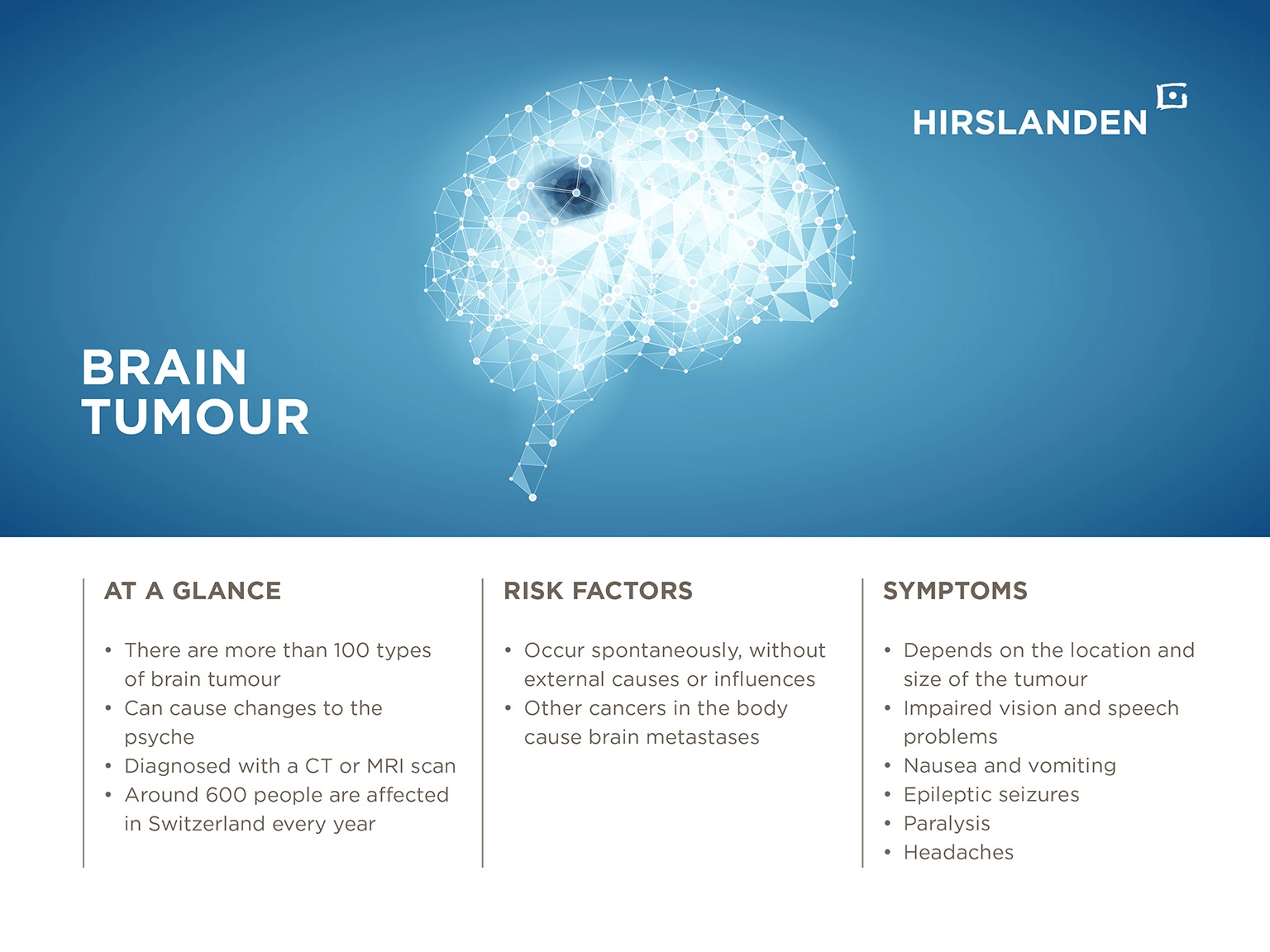

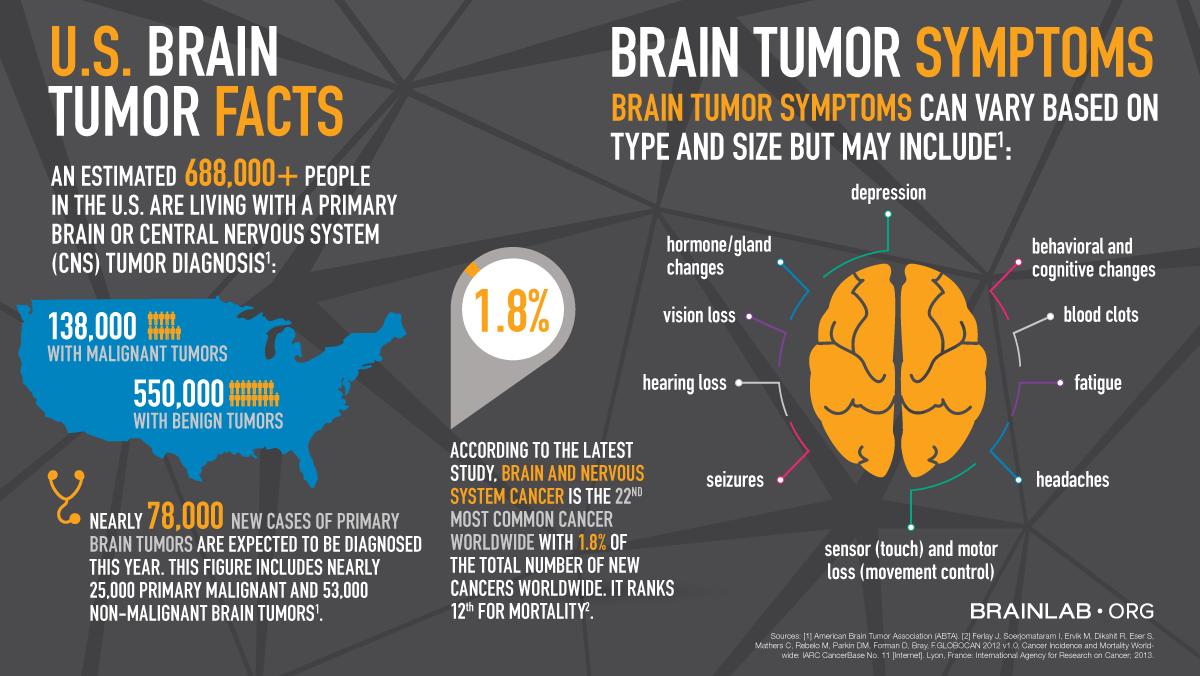

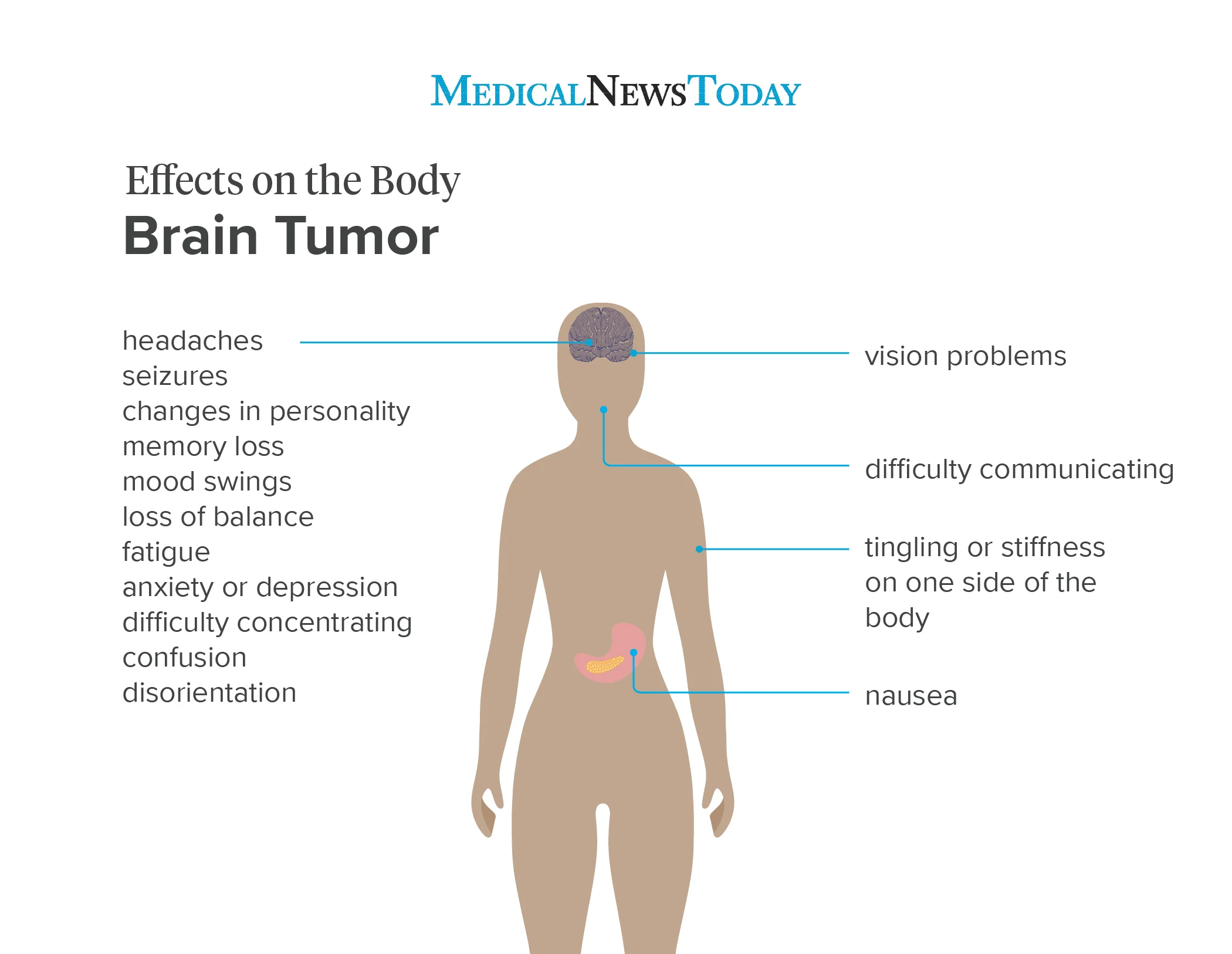

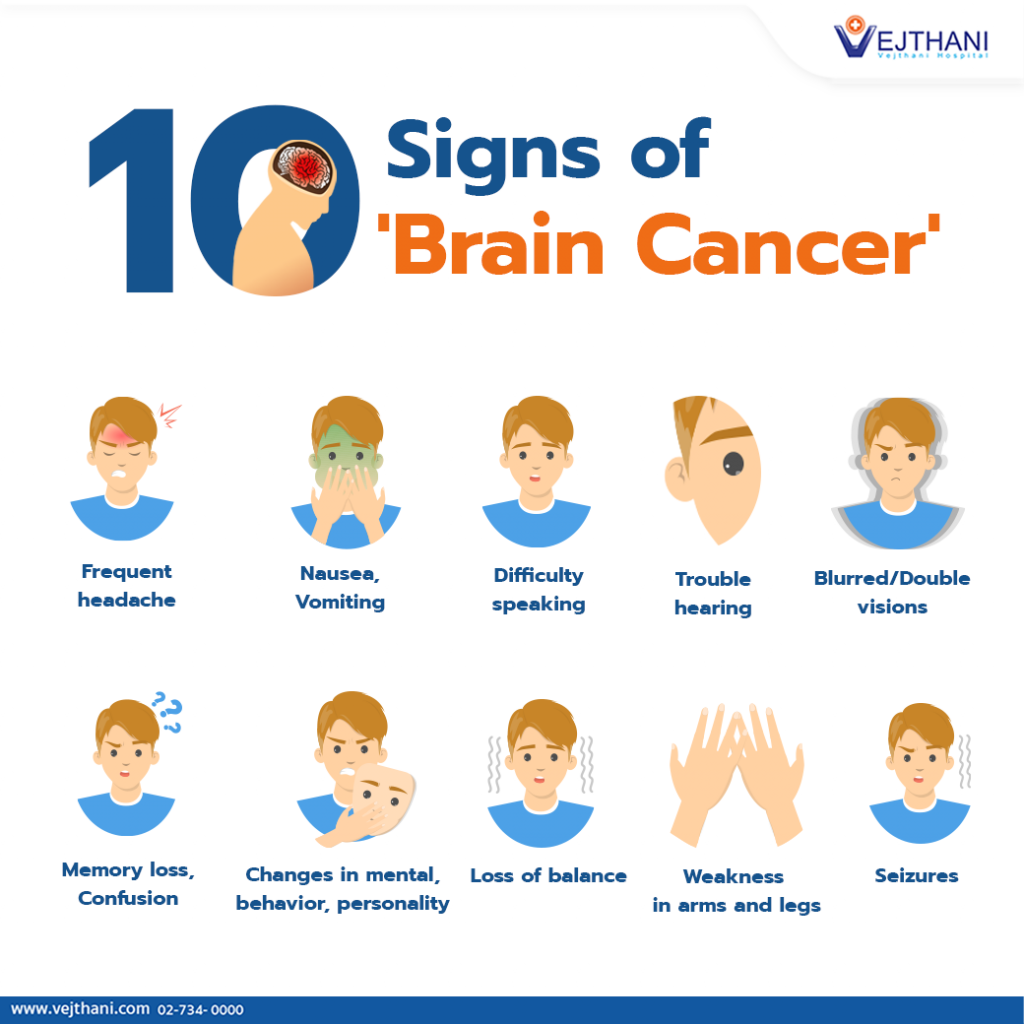

What are the symptoms of a brain tumour?

Brain tumours have a range of symptoms, depending on where the tumour is, how big it is and what type of tumour it is. Some symptoms may also be caused by the treatments used to manage the tumour. Slow growing brain tumours may not have any symptoms to start with.

Many brain tumour symptoms and brain cancer symptoms are similar to those of other diseases and conditions.

Symptoms include:

- headaches — these are often the first symptom of a brain tumour

- seizures

- problems with balance and coordination

- weakness on one side or part of the body

- nausea and vomiting

- confusion

- disturbance

- vision loss

- impaired sense of smell or taste

- drowsiness and fatigue

- dizziness or loss of consciousness

- changes to your personality and how you behave, e.g. irritability

- changes to how you think

- endocrine dysfunction (hormone/gland changes)

You may notice other signs, like memory problems or difficulty speaking or remembering words.

Read more about brain tumours, including symptoms, in the Cancer Council’s guide ‘Understanding brain tumours’.

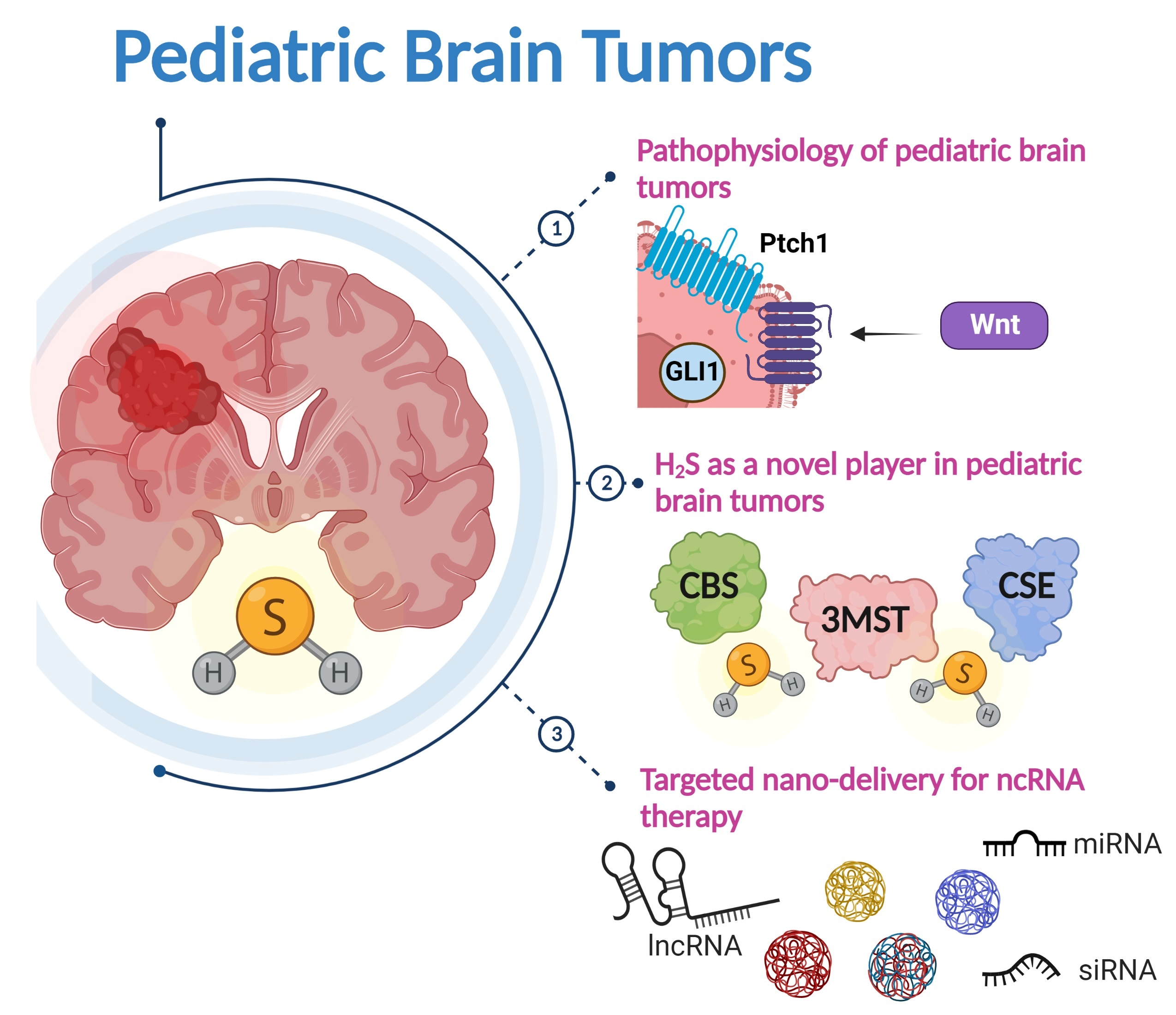

Brain tumour symptoms in children

The symptoms of brain tumours in children include persistent headaches, recurrent vomiting, behavioural changes, abnormal eye movements and balance/coordination problems. There may be blurred or double vision or a child may hold their head in an abnormal position.

If you are worried that your child is not behaving in the normal way, or has other symptoms that concern you, see your doctor straight away.

Seizures (also called ‘fits’) are also a common symptom in children with a brain tumour. If your child is having a seizure, you should call an ambulance on triple zero (000).

What causes brain tumours?

It’s not known what causes brain tumours.

Occasionally people develop brain tumours because of genetic factors, or because they’ve been exposed to very high doses of radiation to the head.

There is no definite link between mobile phones and brain tumours. Researchers continue to investigate the potential causes of brain tumours, including whether certain genes are important riskfactors. Read more about brain tumour research at Cure Brain Cancer Foundation.

How common is brain cancer?

Each year, about 1,900 people are diagnosed with malignant brain tumours (brain cancer) in Australia, including 100-200 children. About 1,500 Australians die of brain cancer each year.

How is a brain tumour diagnosed?

Many people with a brain tumour see their doctor because they don’t feel well or are worried about their symptoms. If your doctor suspects a brain tumour, they may talk to you, examine you and organise other tests. If the results confirm a tumour, your doctor will advise if further tests are required and will discuss treatment options with you.

Physical examination

To investigate the possibility of a brain tumour, your doctor may do a physical examination, which may include:

- checking your reflexes

- testing the strength in your arm and leg muscles

- walking in a line to show your balance and coordination

- testing whether you can feel a pinprick

- brain and memory exercises

- examining your eyes and your eye movements with an ophthalmoscope

If this examination suggests that you may have a tumour, or if your doctor wants to rule out a tumour as the cause for your symptoms, tests may be suggested.

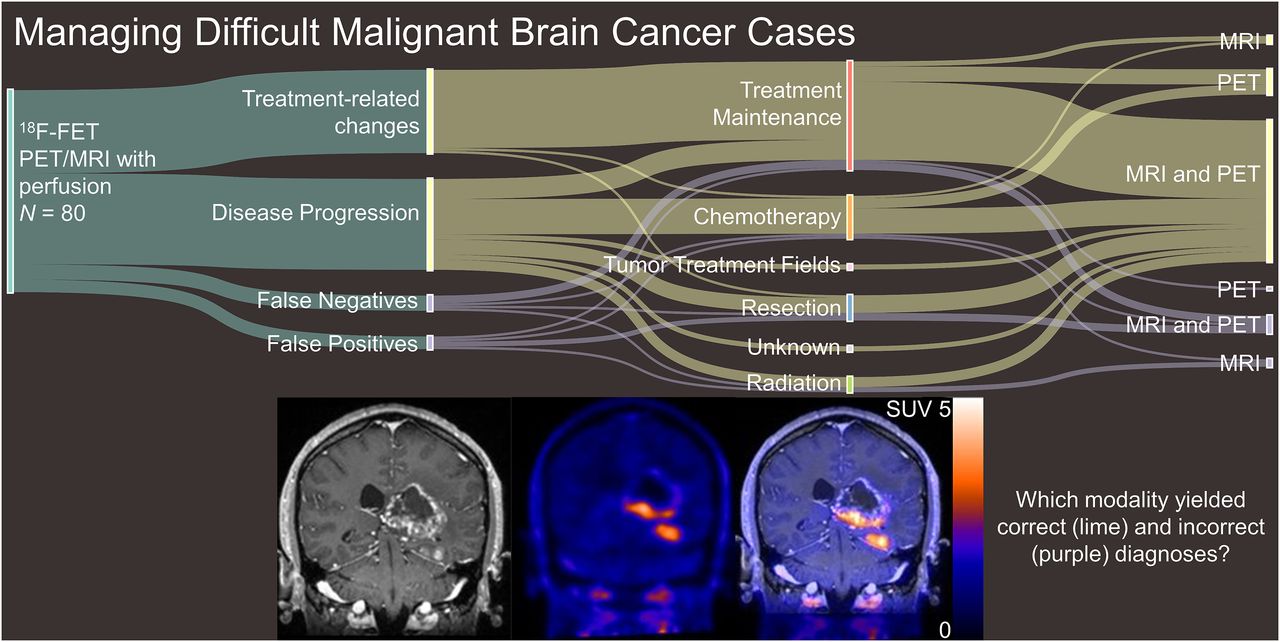

Imaging and diagnostic tests

Tests to diagnose brain tumours may include:

- CT (computerised tomography) scan — this uses x-ray beams to take multiple pictures of the inside of your body

- MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan — this uses magnetism and radio waves to create detailed cross-sectional pictures of your body

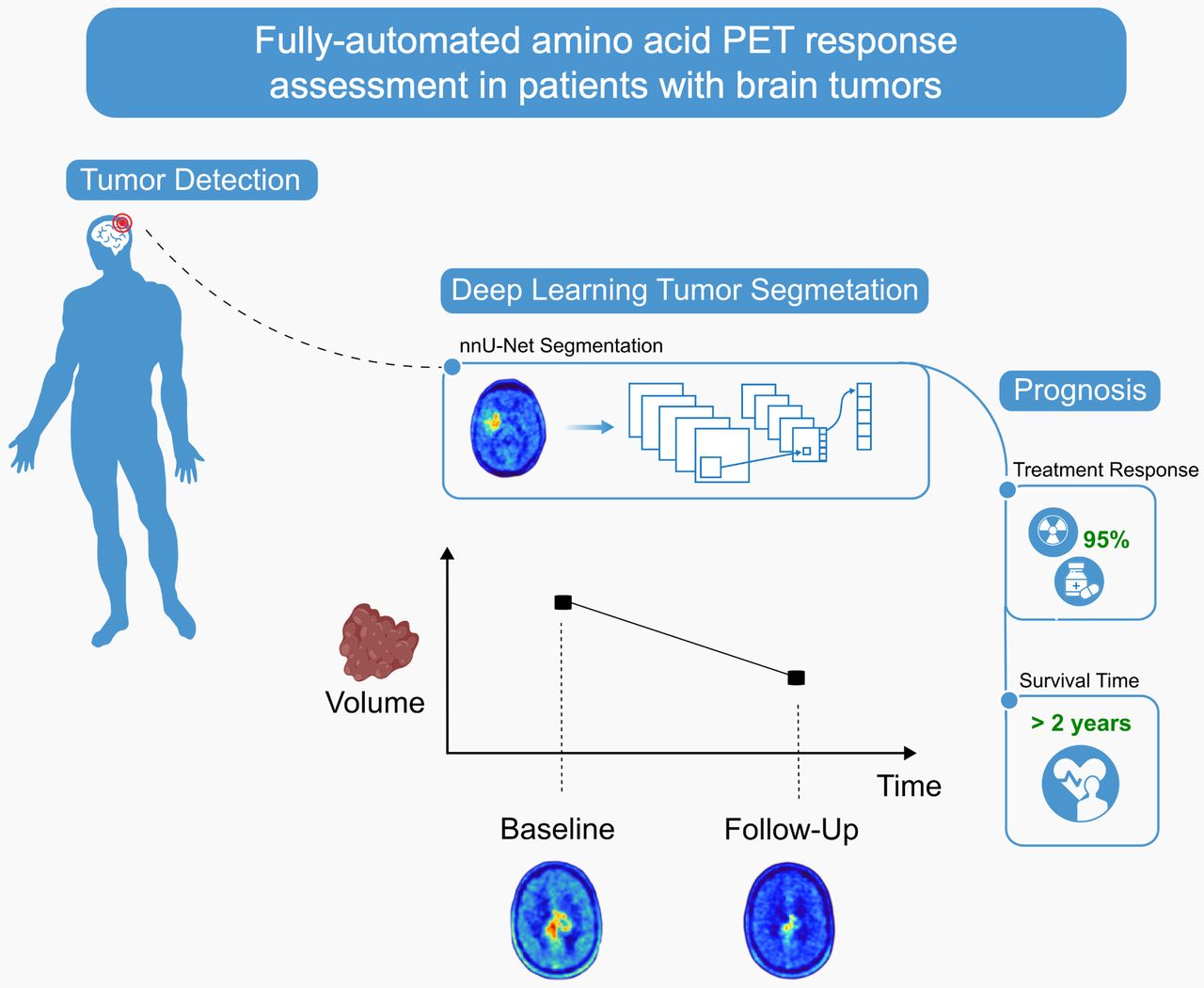

- PET (positron emission tomography) scan — this test requires a small amount of radioactive solution to be injected. The cancer cells show up brighter on this scan as they absorb the solution more quickly than other cells

- lumbar puncture (spinal tap) — to collect a sample of cerebrospinal fluid (fluid around your brain and spinal cord)

- surgical biopsy — where a small piece of tumour tissue is removed under anaesthetic, to be examined

You may also have blood tests to check hormone levels and your overall health.

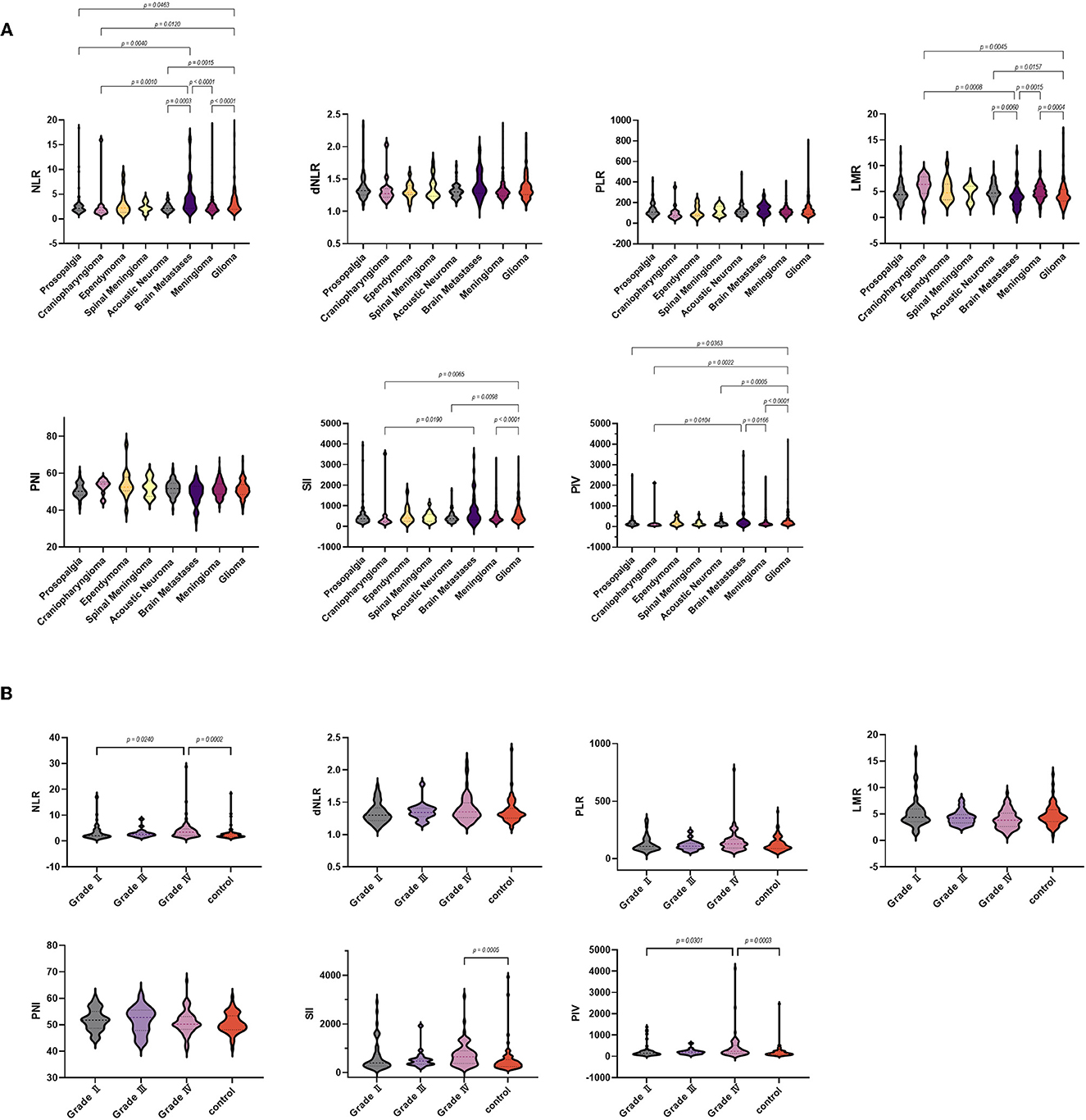

Some of these tests are also used to show how serious your tumour is or how quickly it’s growing. This is called the ‘grade’ of your tumour.

These tests include:

- cerebral angiogram — to examine the blood supply to the area being scanned, especially when a tumour may be deep inside the brain

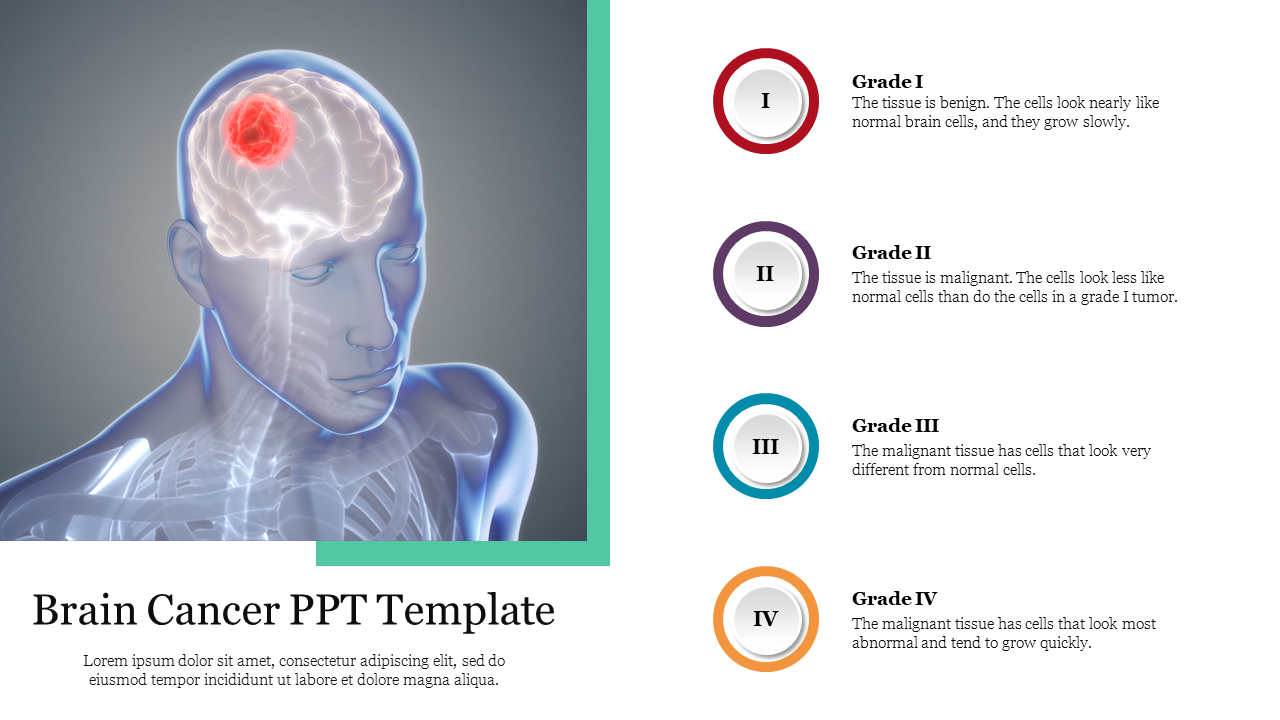

Grading brain tumours

Brain tumours are not ‘staged’ like other tumours/cancers because most don’t spread to other parts of the body — only to other parts of the brain and spinal cord. However, brain tumours are graded.

Brain tumours are usually given a grade from 1 to 4, based on how the cells look. This can also suggest how quickly the tumour may grow. A pathologist works out the grade by looking at the cells under a microscope.

- grade 1 — low-grade tumours, benign, grow slowly

- grade 2 — low-grade tumours, benign, growing at a slow rate. May come back after treatment

- grade 3 — high-grade tumours, malignant (cancerous), growing at a moderate rate, can spread to other parts of brain

- grade 4 — fastest growing, malignant (cancerous), also called high-grade tumours, can spread to other parts of the brain and tend to come back

How are brain tumours treated?

If you are diagnosed with a brain tumour, your doctor will discuss your treatment options with you. Treatment aims to either remove the tumour completely, slow its growth or relieve symptoms by shrinking the tumour.

Suggestions for treatment will be based on:

- your age, health and medical history

- the type, location and size of the tumour

- how fast the tumour is growing, and how likely it is to spread or come back

- your symptoms

- how you may react to different therapies

You may be referred to specialists including:

- oncologist (cancer specialist)

- neurologist (brain specialist)

- neurosurgeon (brain surgeon)

The main treatments for brain tumours are:

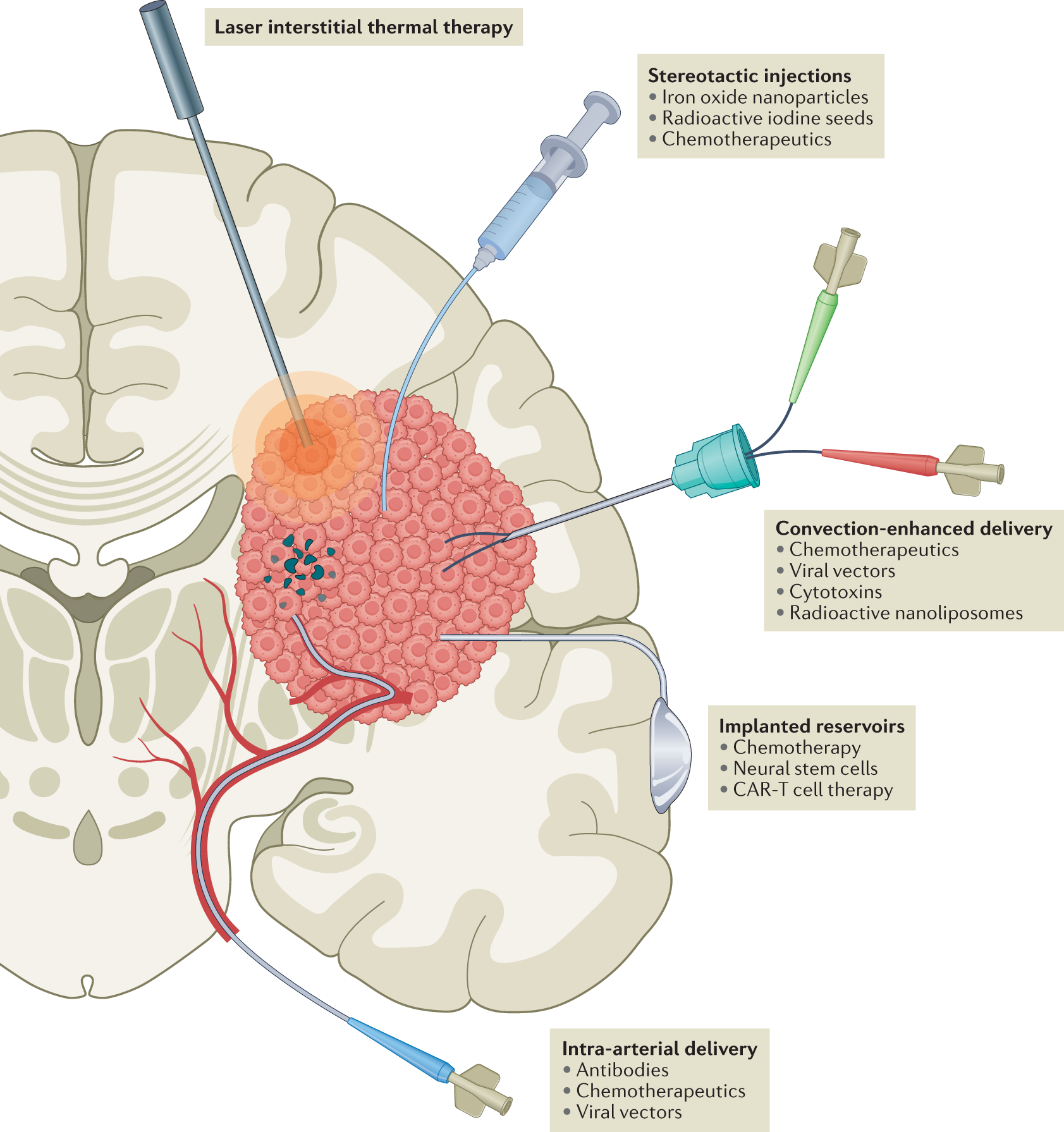

- surgery

- radiotherapy

- chemotherapy

- medications to control symptoms

In addition to standard treatments, doctors may suggest you consider taking part in a clinical trial. Clinical trials are research studies to test new treatments. Read more about clinical trials on the Cure Brain Cancer website.

Talk to your doctor about all options, their side effects and how to manage them.

For information about support options for you, your family and your carers,

Surgery

Surgery for brain tumours aims to remove as much of the tumour as possible, ideally the entire tumour, while minimising damage to healthy parts of the brain.

Sometimes the tumour may not be able to be removed, or some of it may be left behind, because it’s too close to important areas of your brain.

Surgery may also be necessary to:

- relieve pressure on your brain

- reduce the size of the tumour to make it easier to be treated with chemotherapy or radiotherapy

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy (radiation therapy) involves treatment with x-rays to destroy the cancer or delay its growth. Radiotherapy is often given after surgery. It is aimed carefully so that healthy tissue near the cancer is protected. Sometimes radiotherapy is combined with chemotherapy.

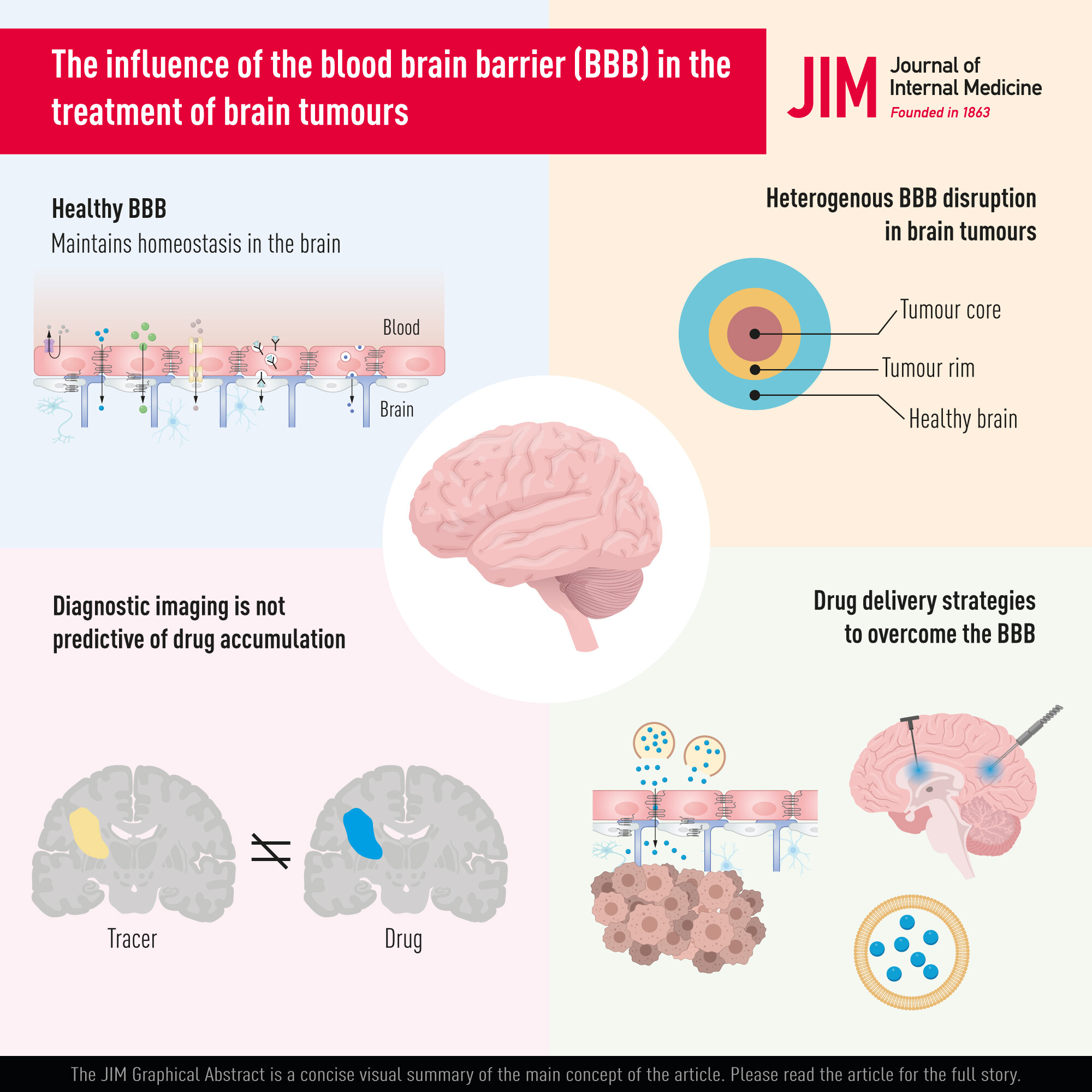

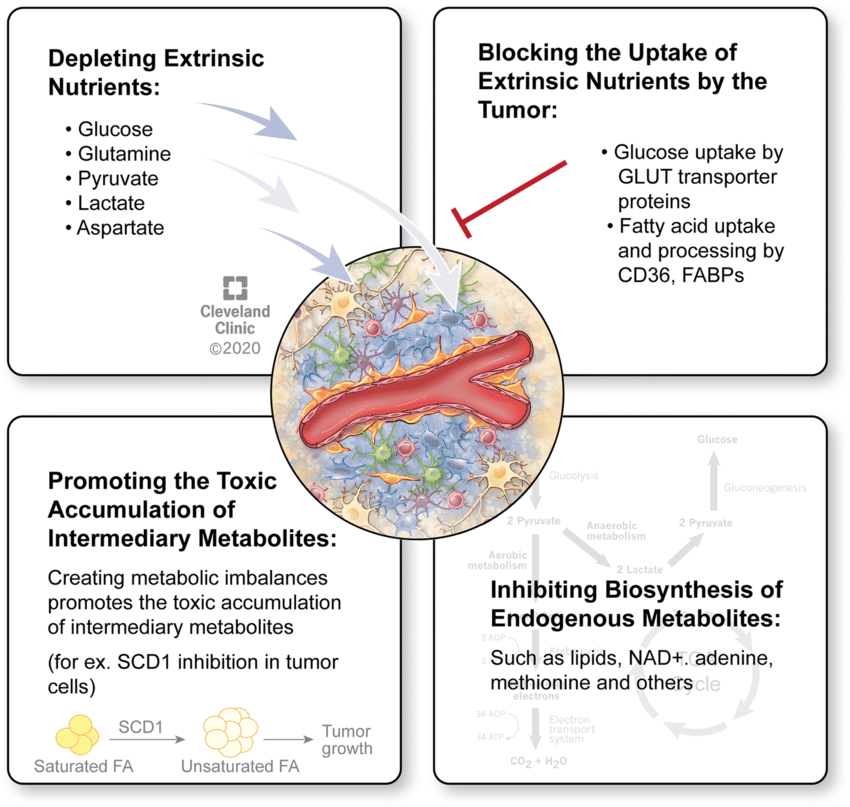

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill cancer cells, while causing as little damage as possible to healthy cells.

Chemotherapy drugs for brain cancer are usually either swallowed, or given through a drip inserted into your vein (intravenously). They travel through the bloodstream killing cells that grow quickly, such as cancer cells.

Chemotherapy may be used to kill cells remaining after surgery, to slow your tumour’s growth, or to minimise your symptoms.

It is often given following surgery and can be given in combination with radiotherapy.

Medications to control symptoms

If you have headaches or seizures you may be given anticonvulsant medication to manage them. Steroids are sometimes given to reduce inflammation around a brain tumour.

Palliative care

Palliative care is the name given to treatment that aims to manage your symptoms and make you as comfortable as possible, without trying to cure your cancer. Palliative care is often given when cancer has reached an advanced stage, but it can also be used at other stages of the illness.

Symptoms caused by treatment for brain tumours

Surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and other treatments can produce symptoms themselves, while they work to reduce the impact of the tumour.

For example, radiotherapy has side effects including nausea and headaches and chemotherapy has side effects that include vomiting and fatigue.