Definition & classification

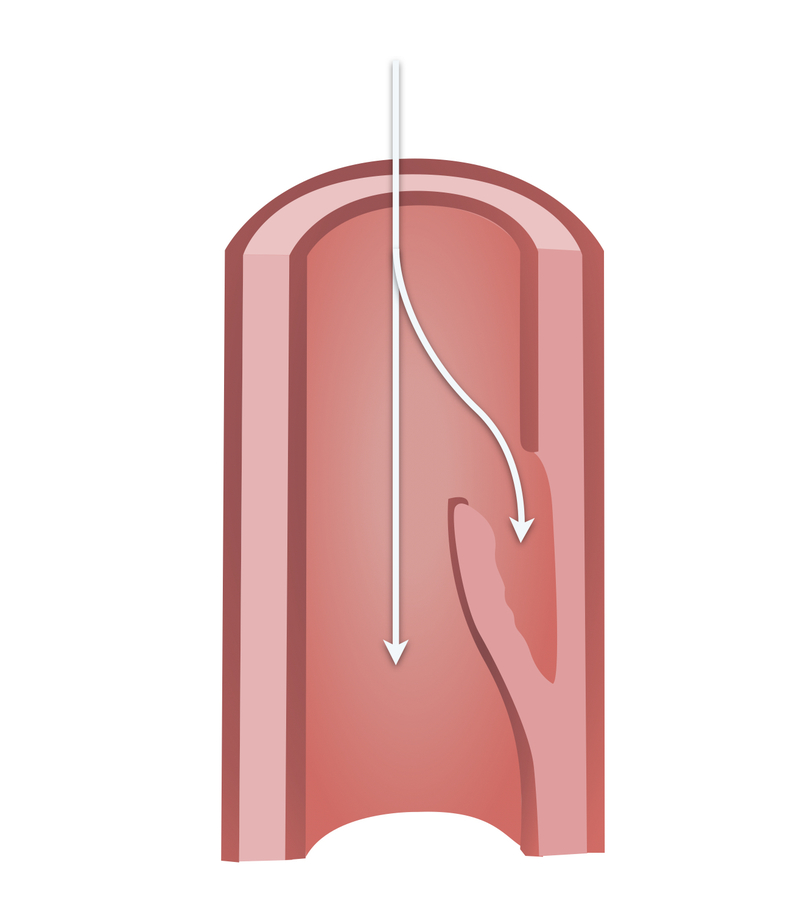

Aortic dissection refers to disruption of the medial layer of the aorta due to blood, leading to separation of the layers resulting in a true lumen and false lumen.

This most commonly results from an intimal tear allowing blood to enter the intima-media space. As this false lumen fills with blood, it may propagate proximally or distally. This results in either rupture through the adventitia or re-entry to the true lumen via a second intimal tear.

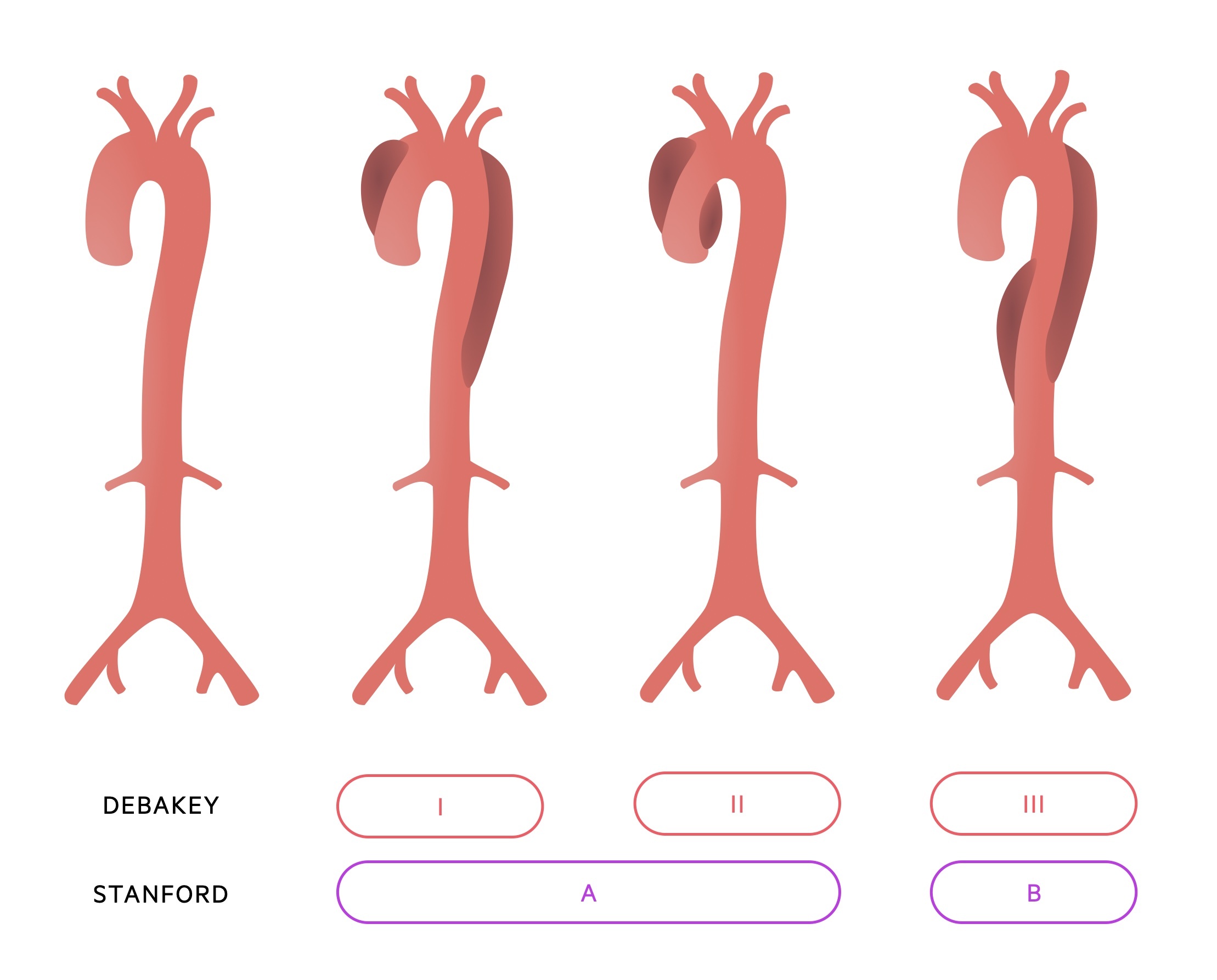

Classification is anatomical with two systems most commonly used, Stanford and DeBakey.

Stanford:

- Type A: Ascending aorta is involved

- Type B: Ascending aorta is not involved

DeBakey:

- Type I: Involves the ascending aorta, dissection extends into arch and beyond

- Type II: Limited to the ascending aorta (proximal to brachiocephalic artery)

- Type IIIa: Involves the descending thoracic aorta (distal to left subclavian artery, proximal to coeliac artery)

- Type IIIb: Involves descending thoracic aorta and abdominal aorta

Aetiology & pathophysiology

The risk factors for aortic dissection may be divided into congenital and acquired factors.

The aorta is composed of three well-defined layers:

- Tunica intima: Inner-most layer composed of endothelium and a subendothelial layer of connective tissue.

- Tunica media: Middle layer, provides strength and elasticity. Composed of smooth muscle, elastic fibres and collagen.

- Tunica adventitia: Outer layer, composed mainly of collagen as well as the vasa vasorum and lymphatics.

Aortic dissection most commonly occurs when an intimal tear allows blood to enter the intima-media space. This leads to the formation of a false lumen. Blood may propagate proximally or distally to the intimal tear.

The pathophysiology of aortic dissection remains poorly understood. Cystic medial degeneration, atherosclerotic ulceration and intramural haematoma have all been implicated. A number of congenital and acquired factors are associated with an increased incidence of aortic dissection.

Congenital:

- Connective tissue disorders (Marfan’s syndrome, Ehlers Danlos syndrome, Osteogenesis imperfecta)

- Turner’s syndrome

- Noonan’s syndrome

- Bicuspid aortic valve

- Metabolic disorders

Acquired:

- Arterial hypertension

- Syphilitic aortitis

- Pregnancy

- Trauma

- Iatrogenic (surgical; aortic cannulation, aortic cross-clamp)

- Cocaine use

Clinical features

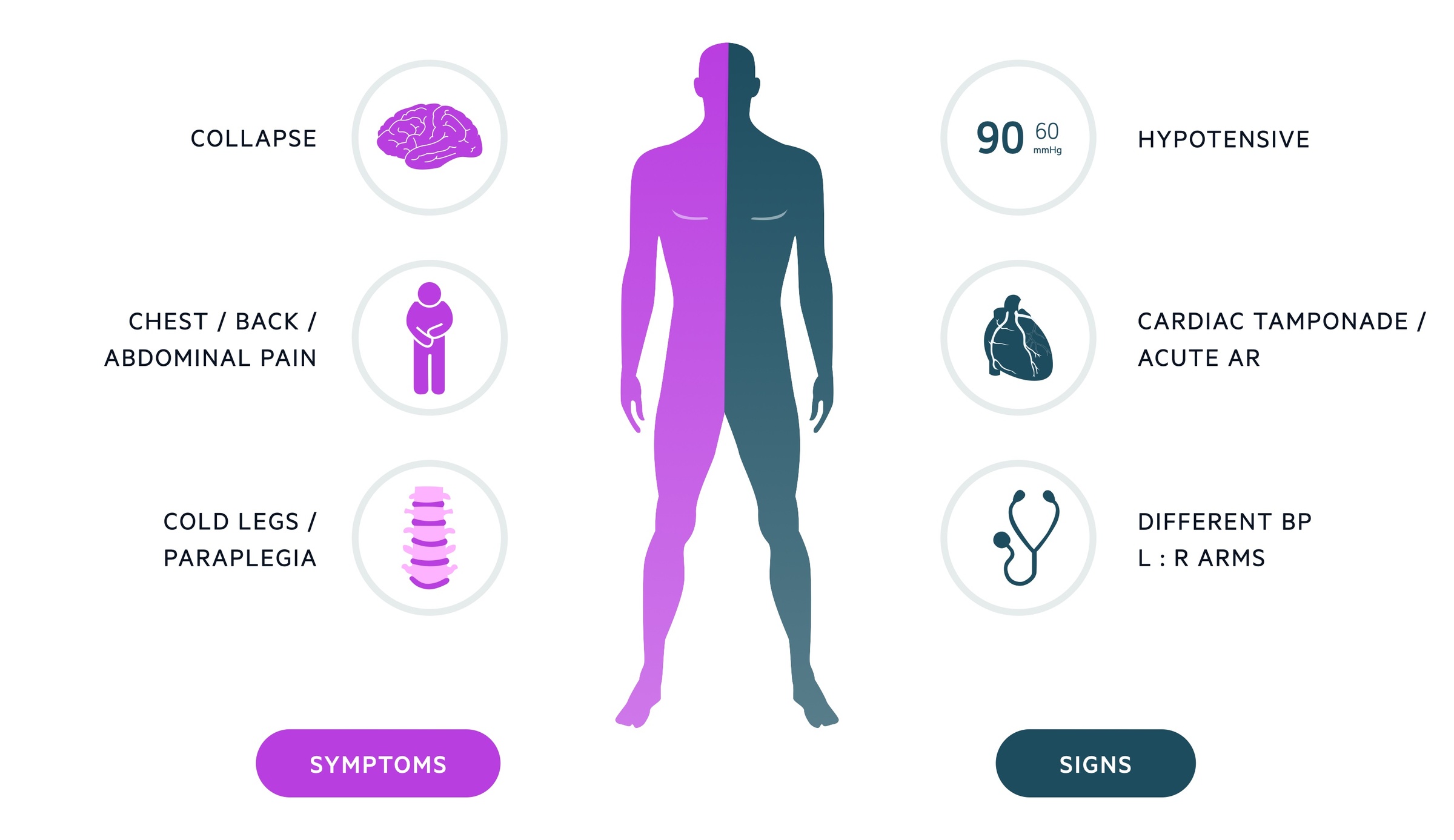

Aortic dissection may present acutely with severe chest pain or the initial dissection may be entirely asymptomatic.

Clinical features may also reflect the development of acute complications of aortic dissection such as cardiac tamponade and aortic regurgitation.

Symptoms

- Chest pain (classically tearing and maximal at onset, though frequently this is not seen)

- Back pain

- Abdominal pain

- Dyspnea

- Syncope / collapse

Signs

- Intra-arm blood pressure differential

- Neurological deficit

- Horners syndrome

- Absent peripheral pulses

Cardiac tamponade

Beck’s triad:

- Raised JVP

- Muffled heart sounds

- Hypotension

Acute aortic regurgitation

- Diastolic murmur

- Wide pulse pressure

- Signs of heart failure

Investigations

A combination of clinical acumen, bedside and laboratory investigations, and imaging may be used to diagnose an acute dissection.

Bedside

- Observations

- ECG (ischaemic changes may be present if the dissection interferes with coronary blood flow)

Bloods

- FBC (leucocytosis may be present)

- U&E

- LFT

- Clotting screen

- D-DIMER (may be elevated)

- Troponin (may be elevated in dissection or indicate the involvement of coronary vessels)

- ABG / VBG

- Group & Save / Cross-match

Imaging

- CXR: May demonstrate a widened mediastinum and left-sided pleural effusion (leaking dissection). Not definitive imaging and may appear normal in a patient with dissection.

- CT Angiogram: Considered definitive imaging in suspected dissection. Requires the patient to be stable enough for transfer and imaging.

- MRI: May be used in renal failure or those with iodine allergies. Disadvantages include it being less available and images take longer to acquire. Often used in the follow-up of patients with chronic dissections or following repair.

- Echocardiogram: Transthoracic echocardiogram may be useful in the assessment of dissections of the ascending aorta. Additionally may be used to evaluate for aortic regurgitation and cardiac tamponade.

Management

Management of aortic dissection depends on the timing of the presentation and the anatomical location.

Stanford Type A

In acute Stanford A aortic dissection emergency surgery is indicated in suitable patients. It carries a mortality of 50% in the first 48 hours in those not undergoing surgical intervention. Despite advances in acute medical and surgical management preoperative mortality remains 10-25 %.

Endovascular repair has been used but is not yet validated in the management of acute type A aortic dissection.

Stanford Type B

In patients with uncomplicated Stanford B dissections, medical management remains the treatment of choice. This involves blood pressure management and appropriate analgesia.

The role of endovascular techniques is still evolving. Thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) may be used in patients with Stanford B dissections with suitable anatomy.

Emergency or urgent surgery may also be indicated in Stanford type B dissections with:

- Intractable pain

- Rupture or evidence of impending rupture

- End-organ damage or limb ischaemia

- Rapid progression

- Marfan’s syndrome

Further Reading: Aortic dissection is a complex condition and its management involves a wealth of nuance. For further information see the ‘2014 European Soceity of Cardiology (ESC) Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases’.