Overview

Renal cell carcinoma is the most common kidney cancer in adults.

It accounts for around 80-85% of kidney cancers. They may be found incidentally on abdominal imaging, present symptomatically (e.g. haematuria, loin pain, loin mass, fever) or with features of paraneoplastic syndromes.

In those with disease spread it may be local, particularly involving invasion of the renal vein and inferior vena cava (IVC) or distant (commonly the lungs). Management is highly dependent on the stage at diagnosis and patient-based factors.

Epidemiology

In 2017, kidney cancers (overall) were the 7th most common cancer in the UK.

There are around 13,000 cases of kidney cancers in the UK each year with incidence increasing over the past decade.

In men, kidney cancer is the 6th most common cancer (8,100 cases), whilst in women it is the 10th most common (4,900 cases).

Types & spread

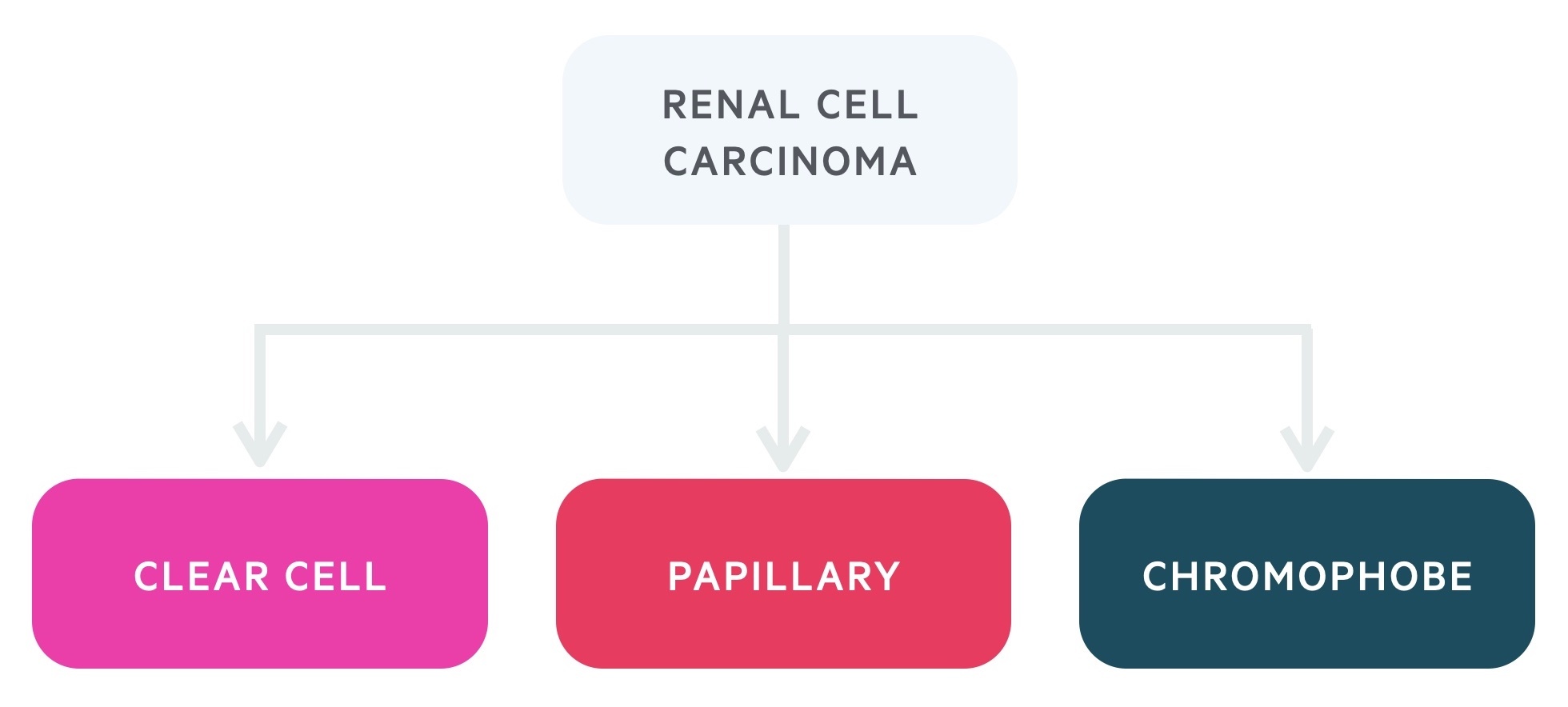

There are three main types of renal cell carcinoma: clear cell, papillary and chromophobe.

Clear cell is the most common type of renal cell carcinoma. It tends to have a worse prognosis than the papillary and chromophobe subtypes. Mutations to the von Hippel-Lindau gene are commonly seen.

Papillary is the next most common and is split into type 1 (associated with mutation to MET) and type 2.

Spread may be local to surrounding structures (e.g. adrenals, spleen or colon) including the renal vein and IVC. The lungs are the most common site of distant spread. Here the characteristic appearance is that of ‘cannon balls’ (large circular white opacifications). Spread to lymph nodes, liver, bones and brain may also occur.

Risk factors

There are a number of risk factors and hereditary syndromes associated with renal cell carcinoma.

- Advancing age

- Smoking

- Obesity

- Family history

- Hypertension

Renal cell carcinoma may also be associated with a number of hereditary syndromes:

- Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome

- Tuberous sclerosis

- Birt–Hogg–Dubé syndrome

- Hereditary papillary renal carcinoma

Clinical features

Renal cell carcinoma may be asymptomatic for much of its development, the ‘classic’ triad of haematuria, flank pain and flank mass is uncommon in practice.

Many renal cell carcinomas are found incidentally on abdominal imaging obtained for other indications. Others may present with symptoms of haematuria, tumour mass effect, tumour burden or paraneoplastic syndromes.

- Haematuria

- Flank pain

- Flank mass

- Fever

- Night sweats

- Malaise

- Weight loss

- Varicocele (classically left-sided)

- Hypertension

- Hypercalcaemia

- Bone pain

Varicoceles may be a sign of renal cancer. The majority of all varicoceles occur on the left side as the left gonadal vein tends to drain at a sharp angle into the left renal vein and is longer than the right draining into the IVC. The vast majority of varicoceles will not indicate cancer, however, tumours that compress venous return (classically left-sided, but the right side may also be affected) can be a cause. As such conduct a close examination and routine investigations and consider referral, particularly in older patients with unexplained new varicocele. Additionally NICE advise urgent referral in those with varicocele which appear suddenly and are painful, do not drain when lying down or a solitary right-sided varicocele.

Paraneoplastic syndromes

A significant number of patients exhibit features of paraneoplastic syndromes at diagnosis.

Paraneoplastic syndromes are relatively rare disorders occurring in patients with cancer typically said to be triggered by an immune response to the malignancy.

According to figures from the European Association of Urology (EAU), up to 30% of patients with symptomatic renal cell carcinoma have paraneoplastic syndromes.

In renal cell carcinoma this may result in (amongst many others):

- Fever

- Hypercalcaemia

- Hypertension

- Neuromyopathies

- Polycythaemia

- Cushing’s syndrome

Referral

All patients with suspected renal cancer should be referred via an urgent (two-week wait) cancer pathway.

NICE guidance NG12, Suspected cancer: recognition and referral advise urgent referral on the suspected cancer pathway if aged 45 and over and have:

- Unexplained visible haematuria without urinary tract infection or

- Visible haematuria that persists or recurs after successful treatment of urinary tract infection

There are other triggers for referral for unexplained symptoms (e.g. weight loss, anorexia), and clinical judgment must be used.

Investigations

CT, USS and MRI may be used to make a diagnosis of renal cancer.

Urine

- Urine dip and MSU

- Urine cytology

Blood

- FBC

- U&Es

- LFTs

- ESR

- Bone profile

A rise in the WCC and ESR is often seen. Hypercalcaemia may be present (and cause clinical presentation).

Imaging

- CT: generally the modality of choice. Though different set-ups and phases may be used to identify primary lesions and metastasis, a triple-phase (renal mass) CT is typically ordered. The thorax should be included if a suspicious renal lesion is identified in the abdomen. CT venogram may be used if renal vein/IVC involvement is suspected.

- MRI: offers excellent diagnostic capabilities and may help identify the likely histology. MRI is often preferred in young patients, pregnant women or those with a contrast allergy. Also used where the diagnosis is unclear.

- USS: renal cell carcinomas are often picked up ‘incidentally’ on abdominal USS. However not as sensitive as CT or MRI so typically not the investigation of choice.

- Bone scan: may be used if bony metastasis is suspected.

Biopsy

A biopsy is not normally required and the decision to undertake one should be made by an appropriate MDT.

Reasons for biopsy include diagnostic uncertainty (e.g possibility lesion is lymphoma or metastasis) or prior to ablative or systemic therapy or lesion surveillance.

Bosniak classification

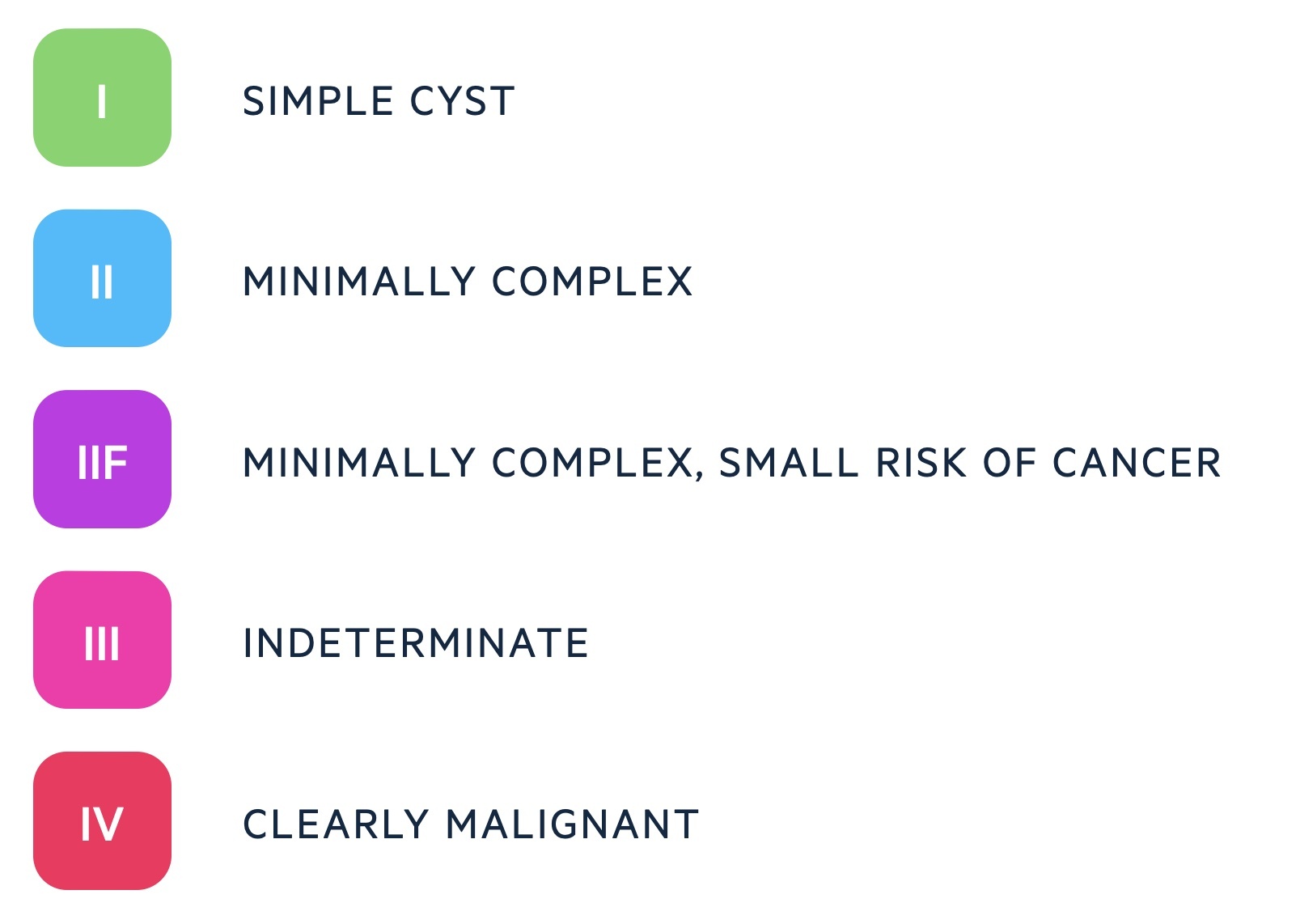

The Bosniak classification may be used to describe renal cysts.

It is a 5-point system based on findings from CT. Bosniak I are never malignant, and malignancy in Bosniak II is very rare.

Bosniak IIF have approximately 5% risk of cancer, III are 31-100% malignant and IV are almost always malignant. All Bosniak IIF, III, and IV are typically discussed at specialist MDT.

Normally Bosniak IIF will be monitored with further imaging. If interested see this paper from Harvard Medical School.

Staging

Renal cell carcinomas are staged using the TNM classification system.

The tumour, node and metastasis (TNM) classification is used for renal cell carcinoma. It assigns a score for each of the primary tumour, nodal spread (if any) and distant metastasis (if any).

A key distinction is made between localised disease as to whether or not the tumour is < 7cm. T1 lesions are less than 7cm whilst T2 are > 7cm – this is one factor that guides the decision to opt for radical or partial nephrectomy. T3/4 involve local spread of disease.

Management

Management is guided by patient wishes, staging and patient-based factors.

The goal of management is to cure or prolong life whilst retaining as much renal function as possible.

Localised disease

As discussed above management is guided by staging. Currently for those with lesions < 7cm (i.e. T1a and T1b) – partial nephrectomy is preferred where possible.

Some with T1a lesions may opt for surveillance and ablation therapy may be used – typically in those who are not good surgical candidates.

In those with T2 tumours radical nephrectomy is typically preferred. However, in certain circumstances, partial nephrectomy may be considered including:

- Solitary kidney or diseased contralateral kidney

- Those with congenital disease at risk of further tumours

When possible laparoscopic +/- robotic assistance is preferred.

Advanced disease

In appropriate patients, nephrectomy may be considered, even in the presence of metastatic spread – and may offer a survival benefit. Selective metastasectomy (surgical removal of metastasis) can also be considered.

There are a number of systemic therapies are available:

- Sunitinib: inhibitor of tyrosine kinase receptors

- Pazopanib: inhibitor of tyrosine kinase receptors

- Temsirolimus: inhibitor of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)

- Everolimus: inhibitor of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)

Radiotherapy may be used – typically for symptomatic relief (e.g. brain metastasis).

Care involves specialist urology, radiology, specialist nurses and palliative care.

Prognosis

Prognosis is dependent on staging and histological grade of the renal cell carcinoma.

According to the European Association of Urology, the overall 5-year survival is 49%.

Figures from Cancer Research UK (accessed Nov 2021) indicate a 1-year survival of 96% in stage 1 disease which falls to 39% in stage 4 disease.