Overview

Prostate cancer is the most common malignancy affecting men in the UK.

Incidence increases with advancing age and men of Black ethnicity are more commonly affected. It can affect men, trans women, non-binary (assigned male sex at birth) and some intersex patients.

Localised disease is commonly asymptomatic but symptoms often develop in locally advanced and metastatic disease.

Management is dependent on a multitude of factors but may involve active surveillance, androgen deprivation therapies, radiotherapy, chemotherapy and surgical intervention.

Epidemiology

1 in 6 men in the UK will be diagnosed with prostate cancer in their lifetime.

In the UK it is the most common malignancy in men with around 52,000 diagnosed with prostate cancer each year. Approximately 12,000 men die each year from prostate cancer.

The prevalence increases with advancing age with incidence peaking between the ages of 75-79. Black men are at greater risk of developing prostate cancer and have a higher mortality when compared to White men.

Figures from Cancer Research UK.

Risk factors

The aetiology of prostate cancer is poorly understood though a number of risk factors have been identified.

- Age

- Black ethnicity

- Family history

- Obesity

Pathophysiology

Our understanding of the exact aetiology and pathophysiology of prostate cancer is still limited.

As with all malignancies, prostate cancer occurs when aberrant cells develop, divide and are not responsive to normal cellular control mechanisms.

The majority of prostate cancers (95%) are adenocarcinomas. Other, much rarer, forms include transitional cell, squamous cell and neuroendocrine cancers.

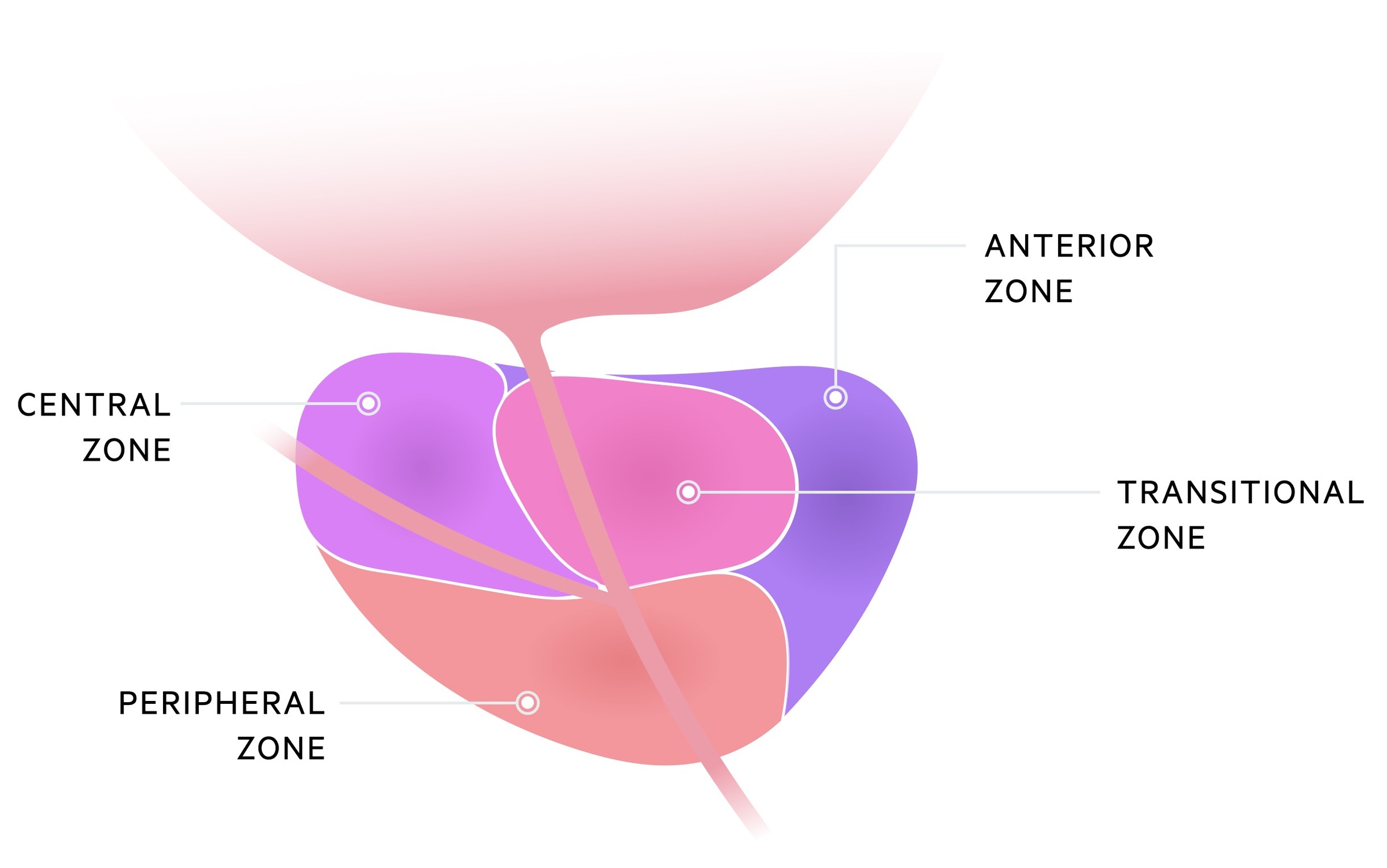

The majority of cancers arise in the peripheral zone of the prostate (around 70%) with 10-20% arising from the central zone and 10-20% arising from the transitional zone.

Clinical features

Prostate cancer is frequently asymptomatic, but as disease progresses a number of symptoms may be encountered.

- LUTS:

- Nocturia

- Frequency

- Hesitancy

- Urgency

- Dribbling

- Overactive bladder

- Retention

- Visible haematuria

- Abnormal DRE (hard, nodular, enlarged, asymmetrical)

- Symptoms of advanced disease (e.g haematuria, blood in semen, lower back pain/bone pain secondary to bony metastasis, weight loss, anorexia)

DRE

Digital rectal examination (DRE) may reveal a malignant feeling prostate.

Findings of cancer include enlargement, asymmetry, nodules and hardness of the prostate. It should be noted, many men with prostate cancer will have a normal DRE.

DRE should be considered in men with:

- Lower urinary tract symptoms (e.g. nocturia, frequency, hesitancy, urgency or retention)

- Haematuria

- Unexplained symptoms that may be explained by advanced prostate cancer (e.g lower back pain, bone pain, weight loss)

- Erectile dysfunction

- Other reasons to be concerned of prostate cancer (e.g. elevated PSA)

PSA testing

Prostate specific antigen is a protein produced by prostate epithelial cells.

PSA is produced by normal prostate tissue, however levels in the blood tend to increase in malignancy. As part of normal physiology it is released into prostatic fluid to help liquefy sperm. It may be used both in the diagnosis and surveillance of prostate cancer.

Before testing men should not have:

- Active or recent UTI (last 6 weeks)

- Recent ejaculation, anal sex or prostate stimulation

- Engaged vigorous exercise for 48 hours

- Had a urological intervention in the past 6 weeks

Asymptomatic testing

The indications for PSA are complicated. There have been a number of studies that have tried to establish if a screening programme would be an overall benefit to the population. Currently there are a number of situations where PSA testing would be recommended. A full discussion regarding the PSA test (including the fact there are other causes of an elevated PSA, and a normal PSA does not exclude cancer) should be had with the patient.

PSA testing can be discussed with men over 50, and should be offered to those men over 50 who request it. An information leaflet is available for patients. It makes clear there are both benefits and potential harms from having a PSA test when otherwise well.

Symptomatic testing

Specific clinical triggers to consider a PSA test include:

- Lower urinary tract symptoms (e.g. nocturia, frequency, hesitancy, urgency or retention)

- Visible haematuria

- Unexplained symptoms that may be explained by advanced prostate cancer (e.g lower back pain, bone pain, weight loss)

- Erectile dysfunction

Referral

All men with suspected prostate cancer should be referred on the urgent cancer (two week wait) pathway.

NICE guidance NG12, Suspected cancer: recognition and referral advise urgent referral on the suspected cancer pathway if the following is found:

- Abnormal prostate (‘feels malignant’) on DRE

- PSA level is elevated above age-specific range

Clinician discretion must be used, a normal PSA and normal DRE do not exclude prostate cancer. If the diagnosis is suspected the patient should be discussed/referred for further review.

Diagnosis

Multiparametric MRI is now commonly the first line investigation in the diagnosis of prostate cancer.

Multiparametric MRI

Recent NICE guidelines (NG 131) advise multiparametric MRI as the first-line investigation in those with suspected localised prostate cancer.

NICE also advise the use of the Likert score – a 5-point score based upon the radiologist’s impression of the scan (adapted from Shin et al):

- Clinically significant cancer highly unlikely to be present

- Clinically significant cancer is unlikely to be present

- Chance of clinically significant cancer is equivocal

- Clinically significant cancer is likely to be present

- Clinically significant cancer is highly likely to be present

Multiparametric MRI-influenced prostate biopsy

A guided biopsy is offered to patients with a Likert score of 3 or greater. NICE advise considering omitting biopsy in those with Likert score of 1 or 2 – after discussion of benefits and risks of each option and taking into account patient-based factors.

For the most part, the biopsy will be guided by the MRI images previously acquired with the help of USS.

A negative biopsy does not completely exclude a diagnosis of prostate cancer. Many factors, including Likert score, PSA level, DRE findings and medical history may be considered. Cases may be discussed at MDT, if concern remains high they may require repeat biopsy. Others may have ongoing active surveillance.

Those who do not have a biopsy with Likert score 1/2 and a raised PSA should have ongoing active surveillance with repeat PSAs and review.

Further imaging

Bone isotope scan, CT and further MRI may all be considered to evaluate for distant spread.

Stage and grade

In prostate cancer the TNM classification is used for staging whilst the Gleason score gives the histological grade

TNM

The tumour, node and metastasis (TNM) classification is used for prostate cancer. It assigns a score for each of the primary tumour, nodal spread (if any) and distant metastasis. The full staging is beyond the scope of this note but can be found on the NICE CKS page .

Gleason score

The Gleason score is a histological grade assigned to prostate cancers. From the biopsy, the most common and second most common tumour pattern is assigned a score of 1 to 5 (5 being the highest grade) to give a combined score of 2 to 10.

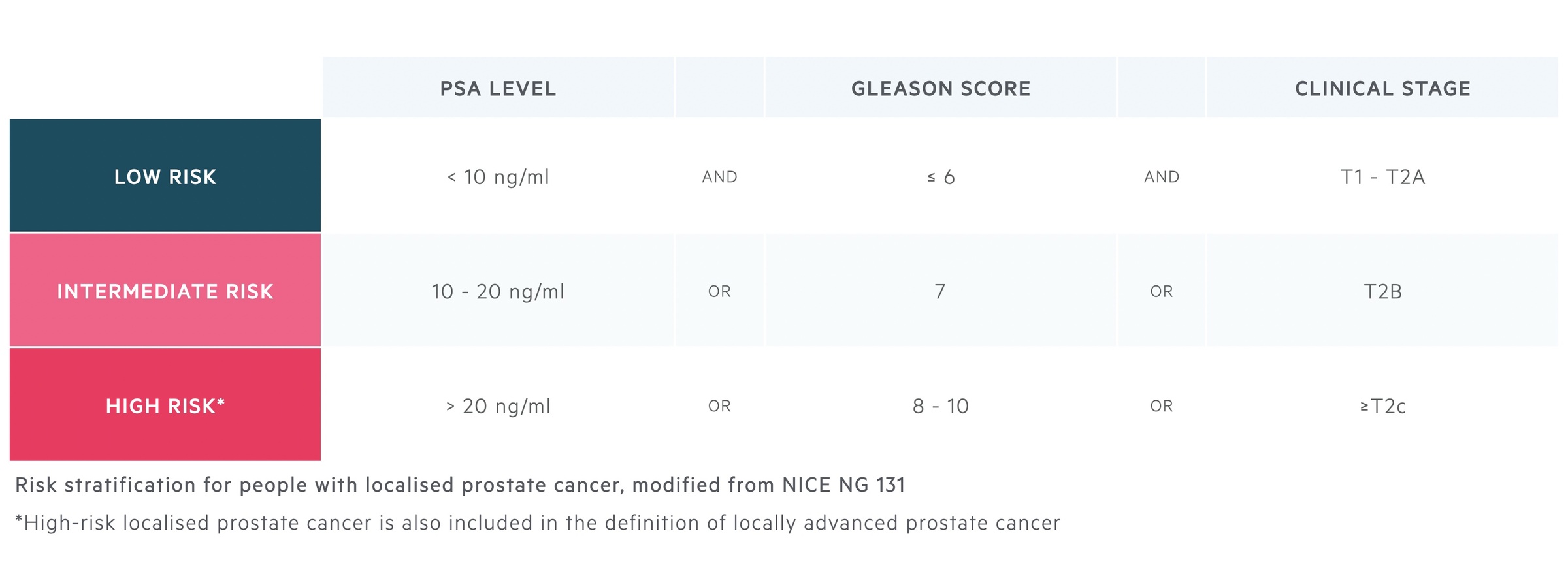

Risk stratification in localised disease

In men with localised prostate cancer, risk can be stratified as low, intermediate and high on the basis the PSA, Gleason score and clinical stage.

Management

Management of prostate cancer may involve multiple modalities including active surveillance, radiotherapy, androgen deprivation therapy, surgery and chemotherapy.

The full management of prostate cancer is well beyond the scope of this note. The goal of this section is to provide a general idea of the basic principles and options, using the NICE guidelines (NG 131) as a framework.

As a student there are a few key management options to be aware of:

- Active surveillance: an option in low-risk localised prostate cancer. It involves regular PSA measurements, digital rectal examinations and multiparametric MRIs. It is used as many with low-risk localised disease will have years without disease progression. Its primary benefit is that it avoids the side effects involved with radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy.

- Radical prostatectomy: is a definitive treatment option for localised prostate cancer. It involves the removal of the entire prostate gland and surrounding tissues. It can be completed as an open, laparoscopic or robotic procedure. Adverse effects include urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction.

- Radical radiotherapy: is a definitive treatment option for localised prostate cancer. There are two main forms of radiotherapy for the prostate; external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) and brachytherapy. EBRT involves external beams of radiation being targeted at the prostate. EBRT may be combined with brachytherapy. Brachytherapy involves implanting radioactive seeds directly in the prostate. Adverse effects again include urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction (though less than radical prostatectomy) as well as bowel symptoms (e.g. faecal incontinence).

- Androgen-depravation therapy: this treatment aims to lower androgen levels – hormones that can stimulate progression in prostate cancer. It can be given to those with intermediate or high-risk localised disease (normally if receiving radical radiotherapy) or in metastatic disease to slow progression. Adverse effects include a loss of libido, erectile dysfunction, loss of ejaculation and osteoporosis. There are a number of options:

- Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist: cause a ‘chemical castration’. GnRH (also called luteinising hormone-releasing hormone or LHRH) is the hormone that stimulates LH/FSH release from the anterior pituitary. Initially it causes an increase in LH/FSH release. However, the persistent presence of an agonist causes downregulation of receptors on the pituitary gland leading to reduced LH/FSH release. Goserelin is a commonly used GnRH agonist (brand name Zoladex).

- Bicalutamide (an anti-androgen)

- Bilateral orchidectomy (castration)

- Docetaxel chemotherapy: is used in non-metastatic high-risk disease as well as locally advanced and metastatic prostate cancer. Docetaxel acts by inhibiting microtubular depolymerisation. Adverse effects include malaise, nausea & vomiting, pneumotoxicity and neutropenic sepsis.

Further management for situations like relapse are not covered here. If interested check out the further reading section.

Localised prostate cancer

Multiple modalities of treatment may be used for localised prostate cancer depending on patient wishes, their individual risk and patient factors. NICE advises three main options:

- Active surveillance

- Radical prostatectomy

- Radical radiotherapy

Each option has its own set of risks and benefits – and as such the patient’s own individual circumstances and wishes are key. The evidence does not show a significant difference in deaths from prostate cancer between each option, however, there is good evidence that both ‘radical’ options reduce the chance of disease progression and development of distant disease.

On the other hand, active surveillance may be associated with a reduced incidence of complications such as urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction.

Depending on the risk (see risk stratification in the ‘Stage and grade’ chapter) different options are advised:

- Low-risk disease: a choice of active surveillance, radical prostatectomy or radical radiotherapy can be offered.

- Intermediate risk disease: NICE advises offering radical prostatectomy or radical radiotherapy. They advise considering active surveillance in those declining radical therapy.

- High-risk disease: NICE advises offering radical prostatectomy or radical radiotherapy. They do not advise active surveillance in high-risk disease.

Androgen deprivation therapy may be combined with radical therapies, particularly those with intermediate or high-risk disease receiving radiotherapy. Brachytherapy may be used in combination with external beam radiotherapy.

Docetaxel chemotherapy may be used in patients with non-metastatic high-risk disease – the indications of which are complex and as always specialist-driven.

Locally advanced prostate cancer

Patients are typically managed with prostatectomy and radiotherapy. Docetaxel chemotherapy may be used.

Pelvic radiotherapy can be considered in patients who are to have neoadjuvant hormonal therapy and radical radiotherapy and have risk of pelvic wall involvement (>15% risk).

Metastatic disease

As with all cases, care should be centered on the patient’s wishes and needs. Input is required from urology, specialist nurses and palliative care.

Docetaxel chemotherapy and androgen deprivation therapy are often used. Bilateral orchidectomy can be offered as an alternative to androgen deprivation therapies.

Prognosis

Overall the prognosis is good, particularly when caught early.

The following figures are taken from Cancer Research UK. In the UK, overall:

- 96.6% survive one year or more after diagnosis

- 86.6% survive five years or more after diagnosis

In those aged 50-69, 95% of men survive for five or more years. Prognosis is however dependent on the staging at the time of diagnosis. Those diagnosed at stage 4 have a 49% survival at five years.