Overview

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is characterised by hyperplasia resulting in lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS).

In BPH, prostatic hyperplasia (increased cell proliferation leading to enlargement) leads to urinary frequency, incomplete emptying, dribbling, hesitancy and nocturia. It may also be complicated by acute or chronic urinary retention.

You may come across the term benign prostatic enlargement (BPE). This refers to a clinical finding on digital rectal examination (DRE), BPH refers to a histological diagnosis.

There is increasing recognition that LUTS in males are often not secondary to BPH. An open mind should be had with regards to the underlying aetiology in men presenting with LUTS.

Epidemiology

BPH is common with incidence increasing with advancing age.

Whilst rare before the age of 40, it affects 30-40% of men older than 50. It is seen in around 90% of men aged 90. Men of African origin are more commonly affected.

Aetiology

The aetiology of BPH is poorly understood.

BPH is common with increasing age. It is a hormone-dependent process involving testosterone and dihydrotestosterone production. A failure of normal apoptosis and abnormal epithelial and stromal proliferation have been implicated.

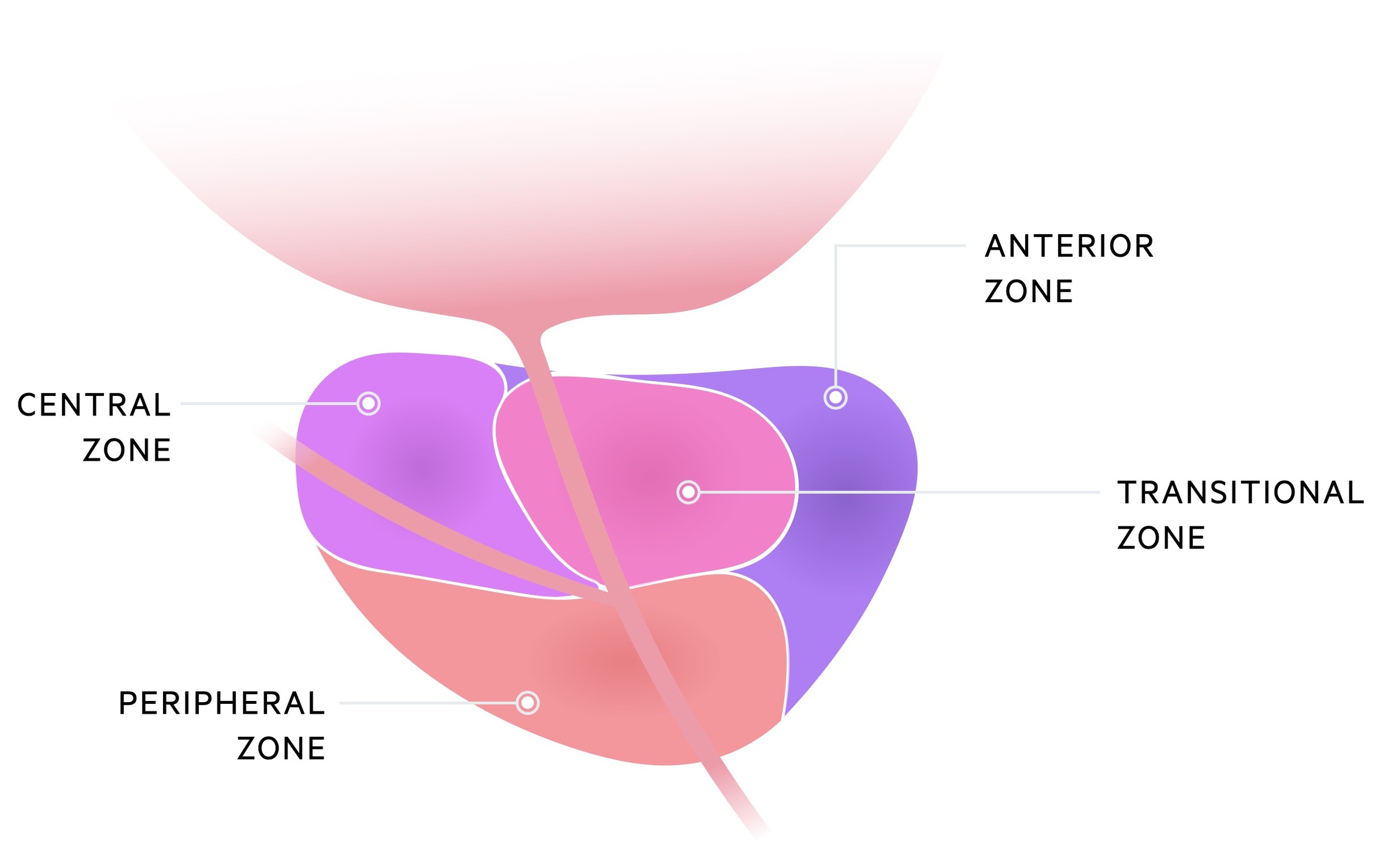

This proliferation occurs primarily in the transition zone of the prostate, this leads to restriction of the prostatic urethra and urinary flow.

Clinical features

Features tend to be those of increased urinary frequency, nocturia and incomplete emptying.

- Urinary frequency

- Nocturia

- Incomplete emptying

- Decreased urinary flow

- Dribbling

- Hesitancy

- Retention (acute or chronic)

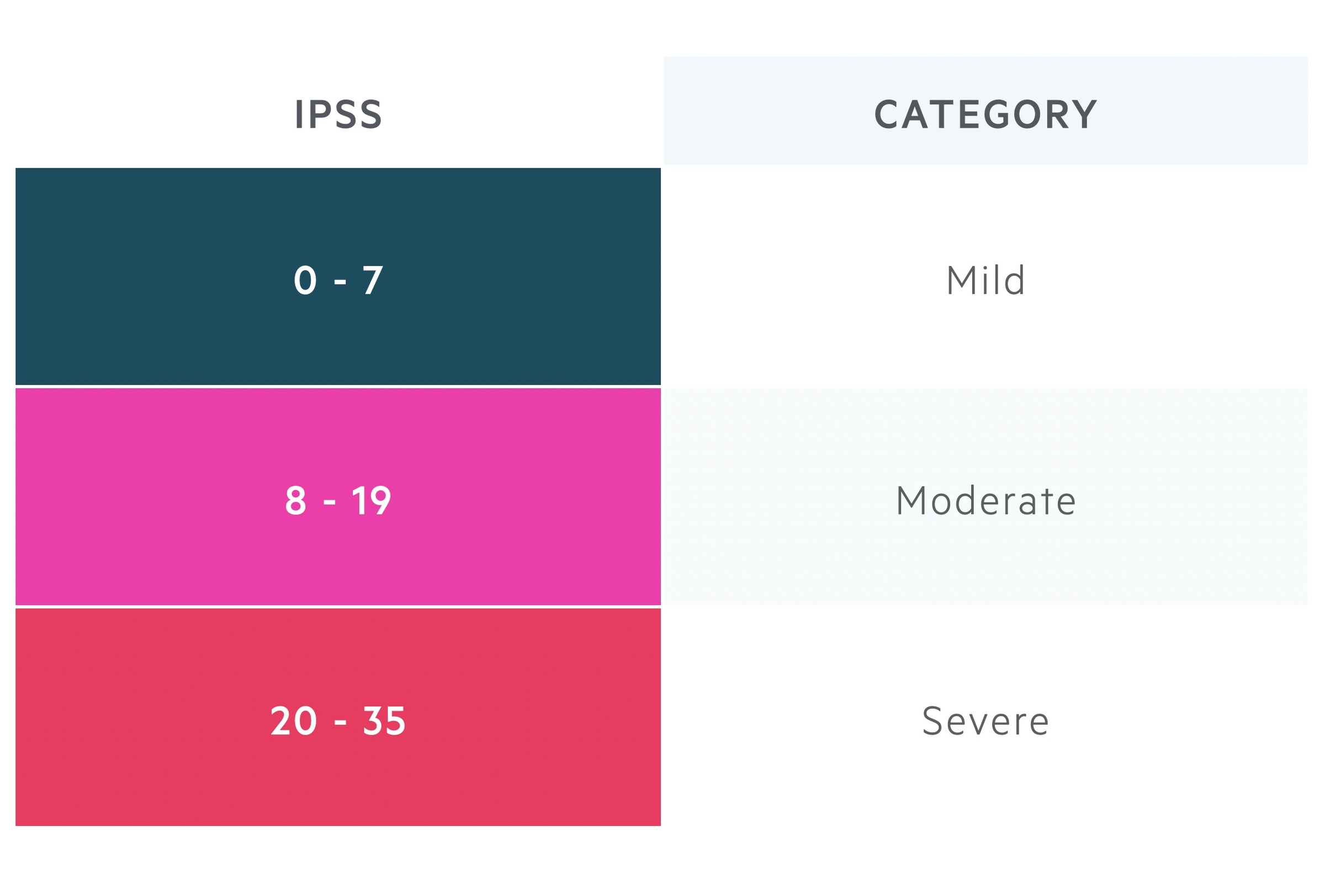

IPSS

The International Prostate Symptom Score is a questionnaire that categorises the impact of prostate symptoms.

It consists of seven questions about symptoms, each of which can be rated 0-5 depending on the frequency with which the symptoms are experienced. The scores of the seven symptomatic questions can be categorised as mild, moderate or severe.

A final (eighth) question asks about quality of life based upon the impact of the disease on a scale of 0-6. Full details of the questionnaire can be found here.

Investigations

Investigations are targeted at confirming the diagnosis, excluding malignancy and assessing for complications.

Digital rectal examination

This is a key component of the examination and allows for assessment of the rough size of the prostate.

Irregular enlargement should raise concerns and further investigation for cancer. Evidence of reduced anal tone may be indicative of neurogenic causes of LUTS.

Urinary

Dip & MSU: in patients with LUTS, infection must be considered. This can be evaluated with a urine dipstick and MSU.

Post-void residual: bladder USS can be used to quantify residual volume (post-void refers to scanning after the patient has passed urine).

Bloods

- FBC

- UEs

- LFTs (ALP may be elevated in prostatic cancer with bony metastasis)

PSA

Helps stratify the risk of prostate cancer. PSA is by no means a perfect test and may be elevated in the absence of malignancy.

Vigorous exercise and ejaculation should be avoided for 48hrs prior to the test. PSA may be elevated in (or following) urinary or prostatic infections or in the 6 weeks following a prostatic biopsy.

Imaging

USS: this can be abdominal or transrectal. It can evaluate the size of the prostate. Also used in patients with urinary retention to evaluate for hydronephrosis.

MRI prostate: typically reserved for evaluation and diagnosis of malignancy.

Uroflowmetry

Urinary flow assessment is a non-invasive test that evaluates urodynamics. Two parameters that you will likely hear mentioned are Qmax (the maximum flow rate) and flow pattern, calculated with a void volume > 150ml. Different threshold values may be used (giving different sensitivities and specificities) and within-subject variability is seen.

Additional investigations

Depending on the differentials and certainty of diagnosis, there are many other investigations that may be ordered. These include voiding cysto-urethrogram, urethrocystoscopy and urodynamics (e.g. filling cystometry and pressure-flow studies).

Management

Management is aimed at reducing symptoms and preventing complications (e.g. urinary retention and infection).

Conservative, medical and surgical methods may be used to treat BPH.

Conservative

Consider watchful waiting in those with mild disease and symptoms. Medical and surgical therapies have complications that may be avoided or delayed.

In certain circumstances, a long-term catheter (changed every 3 months) is used for management.

Medical

Alpha-blockers (e.g. Tamsulosin): these inhibit the action of noradrenaline on the smooth muscle in the prostate resulting in reduced tone. This mechanism does not appear to explain the effect seen and other actions are likely relevant. It is relatively fast-acting, with improvements seen in the first few days of use. Problematic postural hypotension may limit its use. They are known to cause ejaculatory dysfunction but there is some data indicating improved erectile function. Intra-operative floppy iris syndrome (IFIS) may occur with alpha-blockers and the risk appears highest with tamsulosin. Ophthalmologists should be aware of the medication and avoid alpha-blockers in those awaiting cataract surgery. Though they help with LUTS, alpha-blockers do not appear to prevent urinary retention or reduce the proportion that eventually needs surgery.

5-alpha reductase inhibitors (e.g. Finasteride): these reduce the production of dihydrotestosterone (DHT) which mediate androgen effects on the prostate. Finasteride does this via selective inhibition of 5α-reductase type 2. This leads to apoptosis of prostatic epithelial cells and reduction in prostate volume. They take up to 6 months to start having a clinically apparent effect. Medications like finasteride can result in reduced libido, erectile dysfunction and less commonly ejaculatory dysfunction. It should be noted they cause a fall in serum PSA levels – this should be considered when testing for suspected prostate cancer. They have been shown to reduce the rate of acute urinary retention and the need for surgery.

Surgical

Transurethral Resection of the Prostate (TURP): is a common procedure in which a resectoscope is used to resect obstructing tissue. There are a number of complications that can occur. Retrograde ejaculation (up to 75%), urinary infection, need for urinary catheter are all relatively common. Occasionally clot retention, urinary incontinence, urethral stricture and erectile dysfunction may occur. A rare but serious early complication is TURP syndrome.

Transurethral Incision of the Prostate (TUIP): similar to TURP, but just involves incision of the outlet as opposed to resection. Normally only suitable for small prostates (< 30ml). Far lower risk of retrograde ejaculations (20%)

Holmium Laser Enucleation of the Prostate (HoLEP): utilises a holmium laser, a pulsed solid-state laser, to remove prostatic tissue and can be suitable for large prostates. The laser also results in reduced blood loss and often shorter post-operative catheter times and hospital stays. Complications are similar to the ones described above for TURP.

Greenlight laser Photoselective Vapourisation of the Prostate (Greenlight laser PVP): a laser is used to achieve tissue photovapourisation. Initial studies indicate comparable results to other minimally invasive techniques. There may be a higher re-operation rate.

Prostatic urethral lift: a minimally invasive transurethral technique that uses the Urolift device and can be performed under local anaesthetic. Two implants, each with two ‘tabs’ bridged by a suture are used to compress the lateral lobes and open up the obstruction. It has little or no impact on erectile dysfunction or retrograde ejaculation. It is ineffective if there is an obstructing middle lobe and long-term trial data is awaited.

Open prostatectomy: tends to be reserved for very large prostates (> 80-100ml) following discussion of more conservative options. No ejaculate can be produced following prostatectomy and most experience symptoms of urinary urgency, frequency and nocturia. Erectile dysfunction may occur. Prostatic tissue remains and cancer can still occur.

Urinary retention

Urinary retention may complicate BPH

Acute retention

Men presenting with acute urinary retention require catheterisation. Ensure you evaluate for infection and renal impairment that may complicate urinary retention.

Patients require urology review and work-up (particularly if they do not have an existing diagnosis). Typically on the first occasion, a patient may be started on an alpha-blocker and discharged with TWOC (trial without catheter) clinic follow-up. Recurrent retention typically indicates a need for surgical intervention.

Chronic retention

Men with chronic retention should be catheterised particularly where there is renal impairment or hydronephrosis. Often surgery will be advised, though intermittent self-catheterisation or a long-term catheter can be used.