Overview

Necrotising soft tissue infections (NSTIs) are a collection of severe infections characterised by rapidly progressive soft tissue inflammation and necrosis.

Specific examples of NSTIs include:

- Necrotising fasciitis – a term popularized in the 1950s to emphasise the constant feature of necrotic fascia with spread of infection along fascial planes.

- Gas gangrene – soft tissue infection, typically caused by Clostridium perfringens, results in myonecrosis and gas formation within tissues.

- Fournier’s gangrene – refers specifically to necrotising fasciitis of the perineum and scrotum.

NSTIs are usually rapidly progressive, resulting in extensive tissue destruction. They are associated with high morbidity and mortality. Accordingly, prompt diagnosis and treatment are essential.

NSTIs may start as a local infection from an abrasion, laceration or bite. Patients may present with cellulitis, which rapidly progresses with pain disproportionate to the clinical picture. Remember, pain may precede skin changes by 24-48hrs.

Diagnosis of necrotising infections is clinical. Effective management necessitates early recognition, resuscitation and early initiation of antibiotics. Urgent surgical debridement remains the predominant factor affecting mortality. Post-operatively, patients are typically managed within an intensive care setting.

Gangrene

Gangrene refers to the localised death of bodily tissue (i.e. necrosis). This commonly occurs at the extremities (e.g. digits). It can be due to a lack of blood supply or a serious infection (usually bacterial). It can be broadly defined as:

- Dry: tissue is dry. Usually evidence of shrunken, black, necrotic tissue. Often from ischaemia (lack of blood supply).

- Wet: tissue is wet. Usually evidence of oedema, ulceration, and exudate. Often due to a necrotising infection.

Gangrene is a term that is often used synonymously with necrotising infection. ‘Gas gangrene’ is a specific type of necrotising infection, often due to the gas-producing bacteria Clostridium perfringens.

Epidemiology

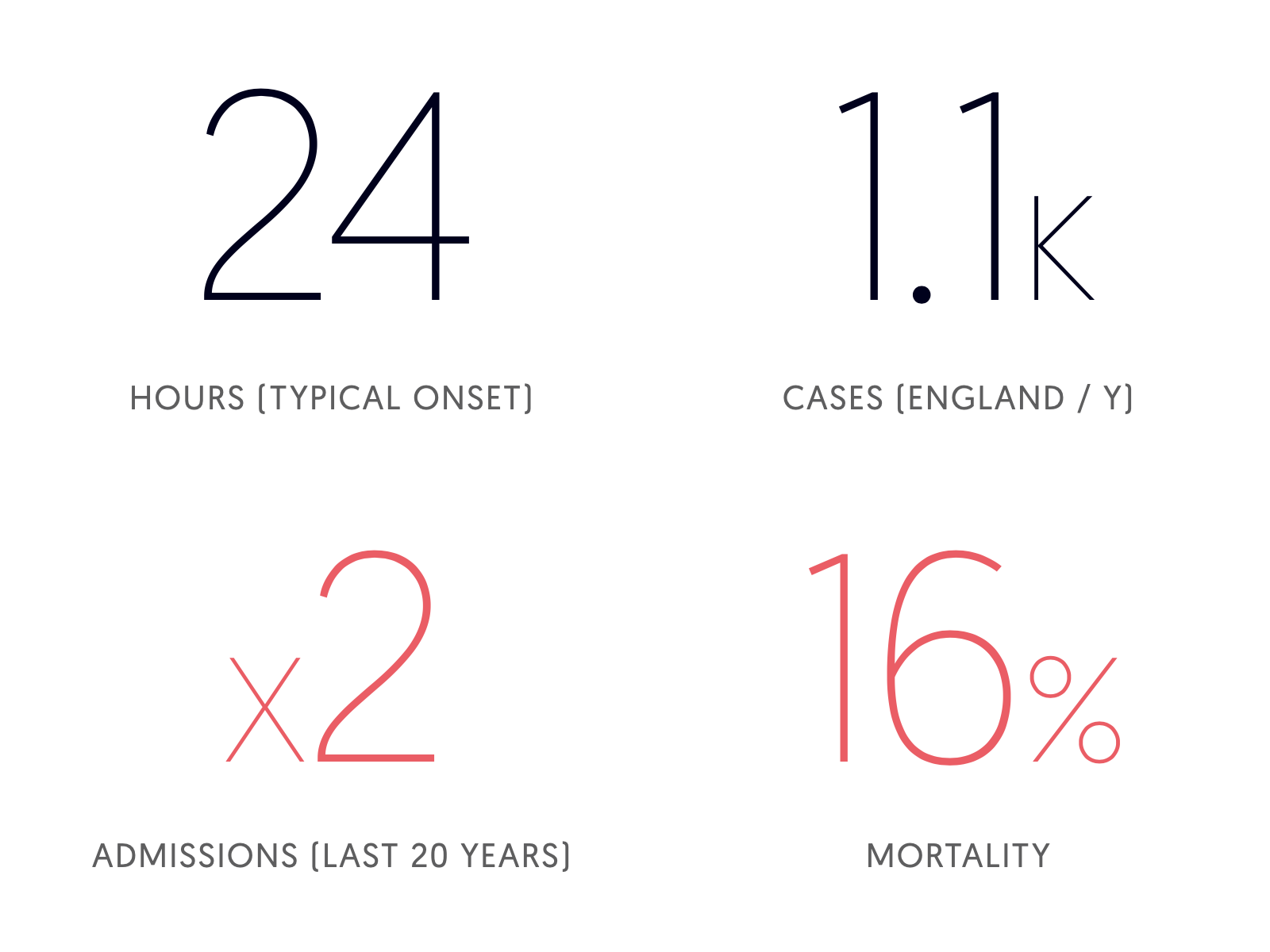

NSTIs are rare, but carry high morbidity and mortality rates.

Although rare, evidence suggests the incidence of NSTIs in England have doubled in the last 20 years and now sit around 1,100 cases per year. The cause for this increase is not clear, however may reflect greater awareness (and thereby increased reporting), increasing bacterial virulence and/or increased antimicrobial resistance. Despite this increase in incidence, age-standardised mortality remains at around 16%.

Statistics from Bodansky et al. (2020).

Aetiology

NSTIs typically occur in the lower extremities, trunk and perineum but rarely involve the face. Commonly there is an inciting cause, such as a laceration or pre-existing infection.

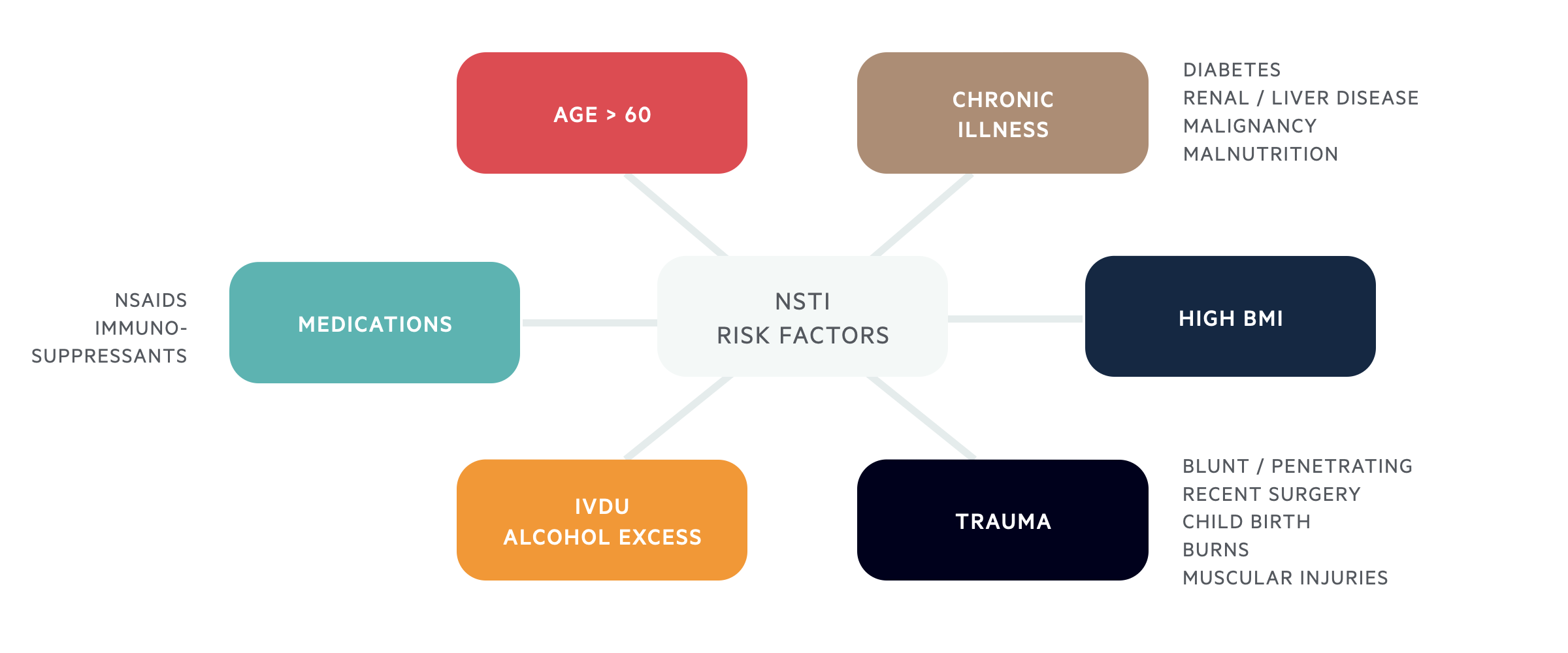

Patients presenting with NSTIs often have some predisposition to infection. Immunocompromise, increasing age, peripheral vascular disease, and obesity are some predisposing factors.

Classification

NSTIs are commonly classified according to the microbial source of the infection.

Types I and II are responsible for the majority of cases of NSTI in the UK. Types III and IV are extremely rare.

Type I (70-80%)

Constitute the majority of NSTIs in the UK, approximately 70-80%. These infections are polymicrobial (typically mixed anaerobes & aerobes, on average four or more organisms) and more frequently occur in the perineal region and trunk.

Patients are typically immunocompromised, diabetic and/or with multiple co-morbidities (peripheral vascular disease, obesity, chronic renal disease, chronic alcohol/drug abuse, HIV etc). Mortality is dependent on time to diagnosis and pre-existing comorbid state. Importantly, NSTIs in these patient groups may present somewhat more indolently and therefore diagnosis may require a higher degree of clinical suspicion.

Type II (20-30%)

Caused by group A streptococcus (Strep. pyogenes +/- Staph. aureus). More commonly affecting the limbs, but truncal involvement has also been reported. Type II infections are associated with toxic shock syndrome. Type II NSTIs can occur in healthy, young, immuno-competent individuals. Frequently, there is a history of recent trauma.

Type III (rare)

Gram-negative monomicrobial infection. Typically associated with Vibrio species infection from seafood ingestion or water contamination of wounds. Carries high mortality despite early recognition.

Type IV (rare)

Fungal infection (typically Candida species, zygomycetes). Typically occur in patients with large traumatic wounds or burns who are severely immunocompromised. Infections tend to be particularly aggressive with mortality of up to 50%.

Pathophysiology

Knowledge of skin and soft tissue anatomy is key.

Knowledge of the anatomy of the skin and fascial planes is key to understanding the pathogenesis of NSTIs and their clinical manifestations.

- Microbial invasion and enzyme release – Initially there is microbial invasion within the superficial fascia (e.g. from minor trauma). The release of enzymes and endo/exotoxins results in rapid spread through the fascial planes.

- Disruption to microcirculation – Thrombosis of the small veins and arteries which pass up through the fascia results in ischaemia to the overlying skin. Early on, these skin changes are NOT obvious, despite extensive infection below.

- Haemorrhagic bullae, ulceration & necrosis – As the infection progresses skin necrosis becomes more evident. In the later stages, signs of profound sepsis and multi-organ failure may appear.

Clinical features

Disproportionate pain compared with physical findings is typical. Pain often precedes skin changes by 24-48hrs.

NSTIs may be initially misdiagnosed as cellulitis or a superficial skin infection. The most distinctive symptom is disproportionate pain compared with physical findings.

Pain often precedes skin changes by 24-48hrs.

Skin changes of NSTIs typically occur in three stages:

- Stage I – Erythema, tenderness, swelling and warmth.

- Stage II – Bullae formation, blistering and fluctuation of the skin.

- Stage III – Haemorrhagic bullae, crepitus and tissue necrosis.

Systemic features include fever, shock and acute kidney injury (indicated by reduced / no urine output).

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of NSTIs is essentially clinical.

The gold standard is surgical exploration and tissue biopsy.

The presence of fascial necrosis with loss of natural tissue planes is diagnostic. IF SUSPECTED DO NOT DELAY SURGICAL EXPLORATION.

LRINEC score

Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotising Fasciitis (LRINEC) score.

A scoring system designed to distinguish between necrotising infections and other soft tissue infections (e.g. cellulitis). A score greater than 6 is highly suggestive of an NSTI (positive predictive value: 92%; negative predictive value: 96%).

The score is based upon:

- CRP

- WCC

- Hb

- Na+

- Creatinine

- Glucose

Management

Prompt resuscitation, broad-spectrum antibiotics, aggressive surgical dedribement & supportive care are essential.

Patients should be managed by an experienced multidisciplinary team – critical care, surgeons (plastics, orthopaedics, general surgeons), anaesthetists and microbiologists.

Resuscitation

Patients’ should be optimised with the aim of establishing adequate tissue perfusion and oxygenation. Resuscitation should be commenced early and be ‘goal-directed’; invasive monitoring and central venous access may be warranted. Given the significant risk of multiorgan failure, patients should be managed in an intensive care facility.

Antibiotics

Antibiotics should be perceived as an adjunct to surgical debridement. Broad-spectrum antibiotics should be initiated without delay according to Trust guidelines. Commonly used agents include:

- Tazocin (piperacillin & tazobactam)

- Meropenem

- Clindamycin – particularly useful at ‘switching off’ exotoxin production.

- Linezolid – similarly inhibits exotoxin production.

Due to the complex microbiology of NSTIs, early discussion with a senior microbiologist is crucial.

Surgical debridement

Timing and adequacy of the initial surgical debridement are key.

Due to the thrombogenic nature of NSTIs, early and aggressive surgical debridement remains the priority. Antibiotics are unable to penetrate infected tissue effectively – thus all necrotic tissue must be excised. Deeper tissues (e.g. muscle) should be inserted thoroughly and excised if needed. Timing and adequacy of the initial debridement is a major determinant of mortality. Debridement may need to be so radical that limb amputation is warranted – with this in mind, it is always wise to coordinate with the appropriate surgical teams early (e.g. Orthopaedics).

Surgical debridement physically removes the nidus of infection and associated toxins. Multiple tissue and fluid samples are often taken at the time of surgery and sent to the microbiologists for analysis. This allows for subsequent refinement of the antibiotic regimen.

Infection is rarely eradicated after a single procedure and serial debridements are often needed (wounds are commonly re-explored in theatre at 24-48 hours time). Further debridement of devitalised tissue may be undertaken at this time.

Supportive care

Effective management of NSTIs necessitates aggressive surgical debridement followed by prolonged supportive care and eventual reconstruction.

Additional considerations include:

- Peri-operative – Anaesthesia is these patients may be particularly challenging. Patient’s may demonstrate considerable haemodynamic instability. During surgery, large blood loss and dramatic fluid shifts should be anticipated.

- Post-operative – Post-operative care is crucial and patients should be monitored in an intensive care facility. Adequate analgesia is essential; patients are commonly sedated or if conscious, initiated on patient-controlled analgesia.

- Ongoing nutritional support – Nutritional support is recognised as an essential component of achieving successful patient outcomes. It is common to initiate early enteral feeding regimens.

Reconstruction

Reconstructive procedures should only be considered when the infection is completely eradicated.

Reconstruction should be delayed until the infection has clinically (and microbiologically) resolved. Multiple swabs and tissue samples are often sent over a prolonged period for culture and subsequent analysis.

Following multiple debridements, patients can often represent a reconstructive challenge. Methods of reconstruction typically follow the reconstructive ladder, with methods employed including:

- Delayed primary closure

- Skin grafting

- Local/regional flaps

- Free tissue transfer

Selection of the most appropriate reconstructive technique typically depends not only on the site and nature of the defect but also on the viability of the underlying and surrounding tissues.

Further reading

Check out the links below for more information on NSTIs.

- Adjunctive hyperbaric oxygen for necrotizing fasciitis (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews).