Summary

Basal-cell carcinoma (BCC) is a slow-growing, locally invasive, malignant epidermal (basal layer) skin tumour.

Typically, a slow-growing skin lesion (over months / years) which commonly occurs on sun-exposed areas of the body. Eighty percent occur on the head and neck.

BCC is the commonest form of skin cancer. It is 4-5x more common than squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). They generally affect middle-aged/elderly individuals, unless there is a genetic susceptibility.

BCCs are locally destructive and rarely metastasize. Clinical examination typically demonstrates a flesh- or pink-colored lesion with rolled edges, ulceration and telangiectasia (small blood vessels).

Treatment is usually by surgical excision, electrodesiccation and curettage (EDC), cryotherapy, or Moh’s micrographic surgery. Rarely, radiotherapy is used.

Risk factors

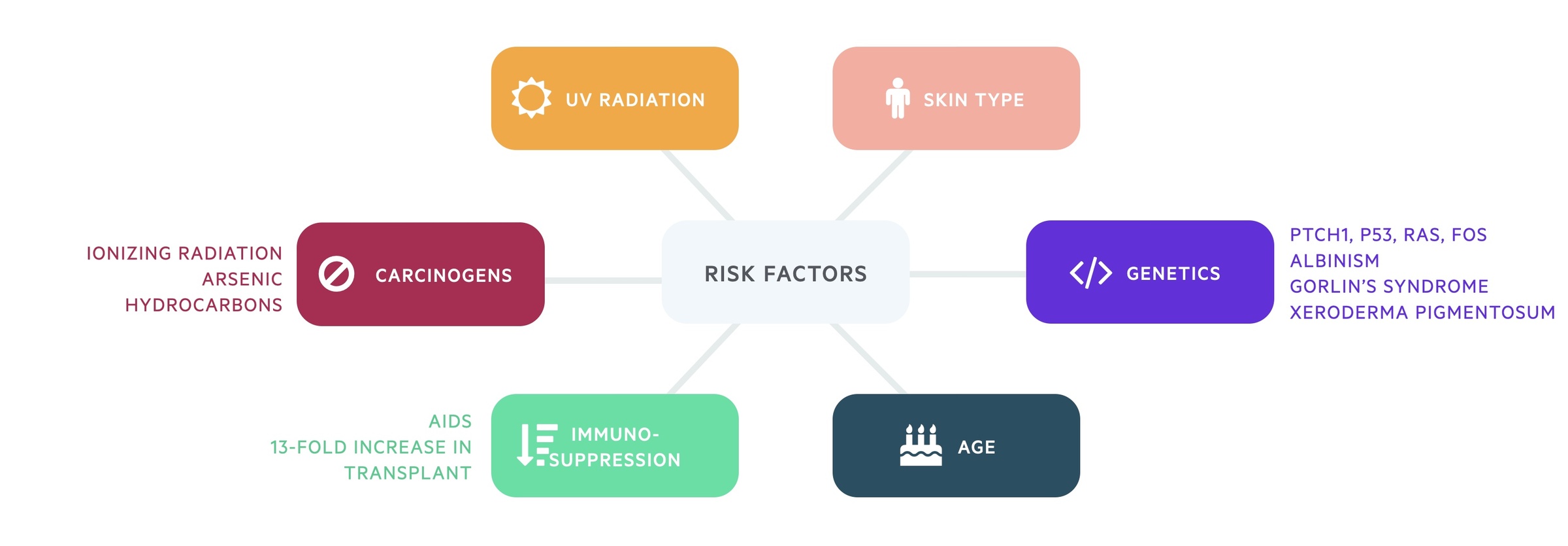

Exposure to UV light is the main aetiological factor.However, UV exposure is not the only risk factor, as roughly 1 in 5 BCCs arise on non–sun-exposed skin.

Other risk factors include:

- Fitzpatrick skin types I & II (light skin, tans poorly)

- Male sex

- Genetics:

- Mutations in PTCH, p53, ras, fos

- Albinism

- Gorlin’s syndrome

- Xeroderma pigmentosum

- Increasing age

- Previous skin cancers

- Immunosuppression (e.g. AIDS / transplantation)

- 13-fold increase in 10-year incidence of non metastatic skin cancer in transplant population vs. general population

- Carcinogens:

- Ionizing radiation, arsenic, hydrocarbons

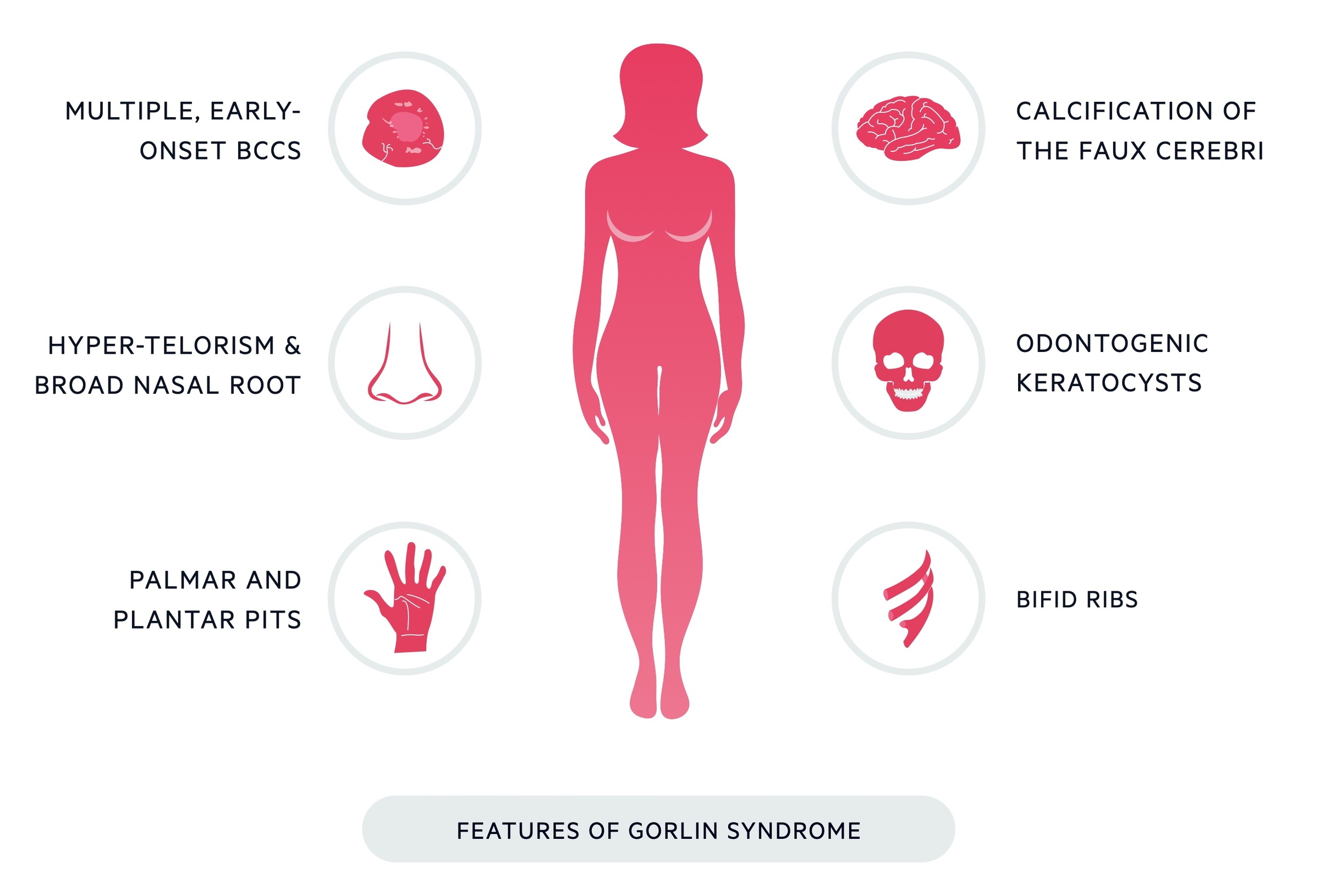

Gorlin-Goltz syndrome

Gorlin-Goltz syndrome or nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (NBCCS) is a genetic condition which greatly increases the risk of developing BCCs.

A rare autosomal dominant condition that occurs as a result of gene mutation, specifically the PTCH1 gene. Individuals with Gorlin syndrome typically begin to develop BCCs during adolescence or early adulthood.

Other clinical features include:

- Broad nasal root

- Hypertelorism (wide-spaced eyes)

- Other:

- Bifid ribs

- Odontogenic keratocysts

- Palmar and plantar pits in the hands

- Calcification of the faux celebri (may be demonstrated on CT)

Clinical features

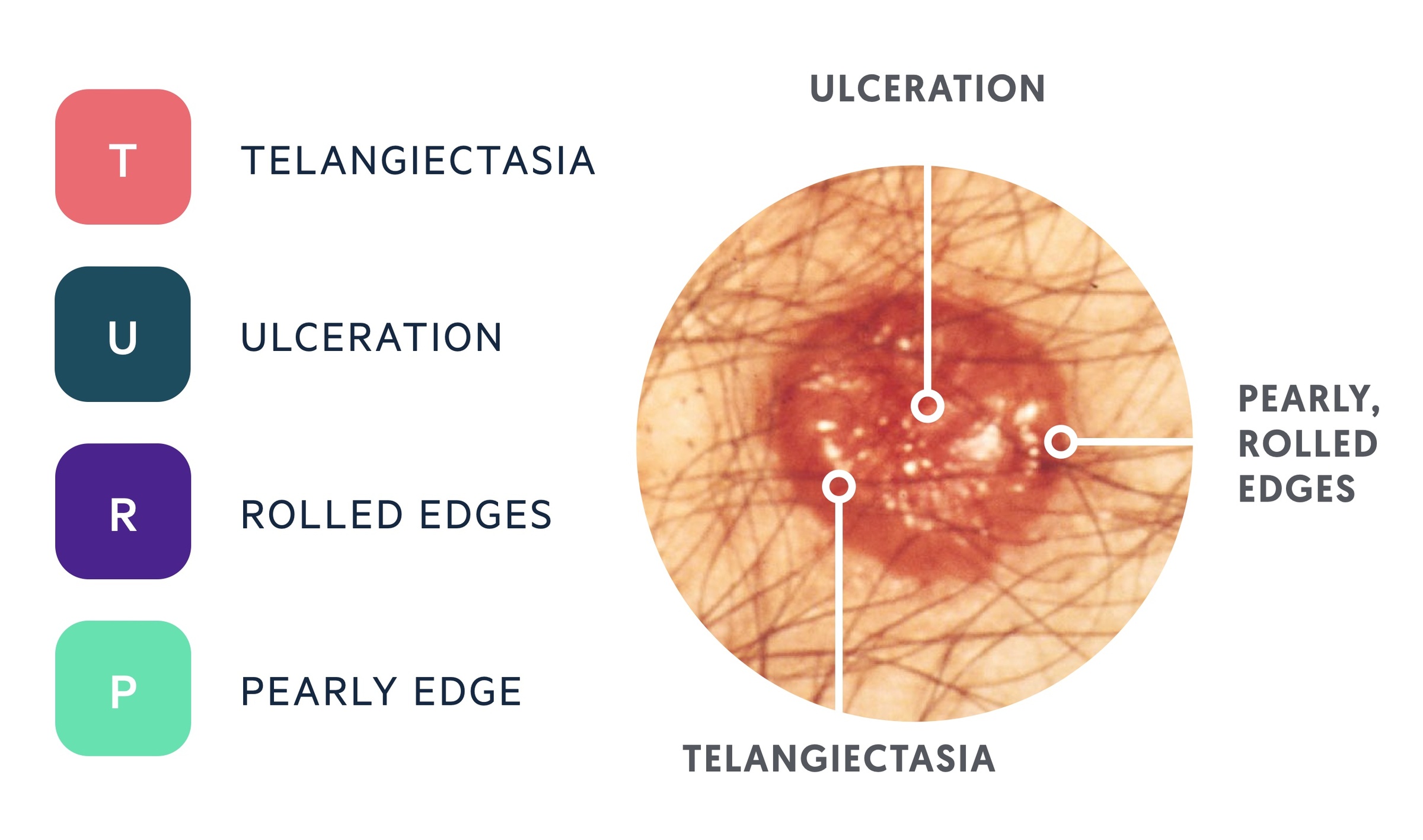

Clinical features of a typical nodular BCC can be remembered with the mnemonic ‘TURP’.

The presence of an irregular pink / skin-coloured lesion; commonly on the face or neck.

- T – Telangiectasia

- U – Ulceration

- R – Rolled edges

- P – Pearly edge

Clinical sub-types

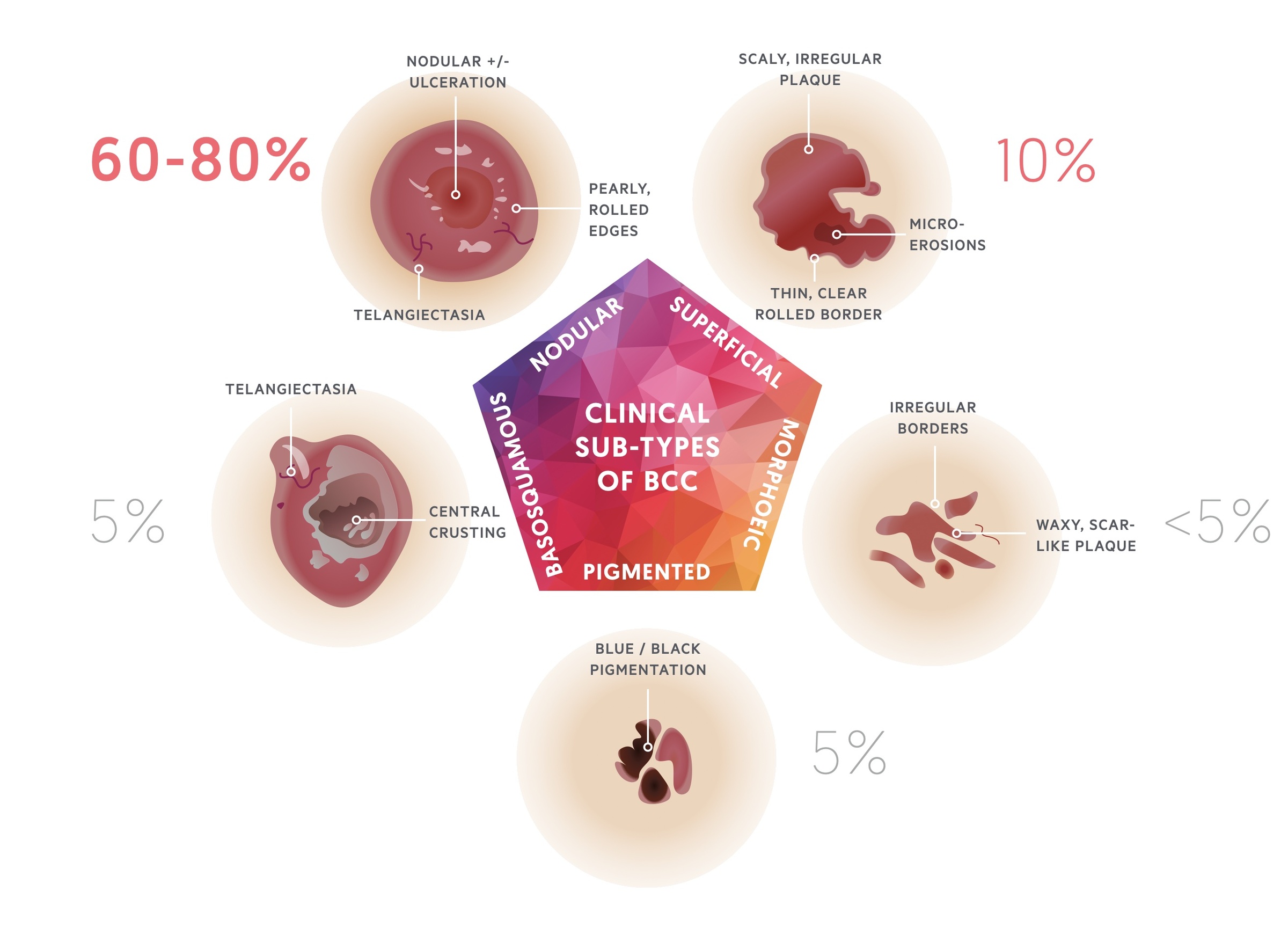

There are several clinical sub-types of BCC, including: nodular, superficial, morphoeic, pigmented & basosquamous.

There are multiple clinical sub-types of BCC described in literature, with some variation between sources. Below are listed five common variants.

1. Nodular BCC

Nodular BCCs comprise about 60-80% of cases and occur most commonly on the head.

Nodular BCCs are red / flesh-coloured and have well-defined borders with overlying telangiectasias. As they grow, they may develop central ulceration (Rodent ulcer).

They commonly arise on the face, particularly on the forehead, temples, nose and upper lip. However, they rarely develop on mucosal surfaces.

A nodular BCC on the face

Image courtesy of Wikipedia Commons

A nodulocystic BCC

Image courtesy of DermNet NZ

2. Superficial BCC

Superficial BCCs present as an erythematous plaque, most commonly on the trunk and limbs.

Superfical BCCs present as slow-growing erythematous plaques that may be dry or crusted or have a slight bluish tinge. They represent approximately 10-30% of BCCs and are often difficult to distinguish from dermatitis or SCC. Occasionally, nodular BCCs can emerge within these lesions. Areas of spontaneous regression areas often present as pale sections with fibrosis. Numerous superficial BCCs may be indictive of arsenic exposure.

A superficial BCC

Image courtesy of Kelly Nelson via Wikipedia Commons

A superficial BCC

Image courtesy of DermNet NZ

3. Morphoeic (Infiltrative) BCC

Morphoeic BCCs present as a scar-like lesion or indentation; they commonly occur on the upper trunk or face.

Morphoeic BCCs are typically difficult to distinguish. They present as a whitish, compact, poorly-defined plaque or scar. They are often deeply invasive.

A morphoeic (infiltrative) BCC

Image courtesy of Kelly Nelson via Wikipedia Commons

4. Pigmented BCC

Pigmented BCCs may be difficult to distinguish from melanoma.

These represent approximately 5% of BCCs. Pigmentation is caused by melanin production, hence why these lesions are often mistaken for melaonomas. In clinical practice, these lesions are often excised with a narrow (2mm) margin in the same manner as any pigmented lesion suspicous of melanoma.

A pigmented BCC

Image courtesy of M. Sand via Wikipedia Commons

5. Basosquamous

A rare, but aggressive form of BCC with increased risk of recurrance and even metastasis.

A contraversial sub-type. Essentially a BCC with differentiation towards SCC. Hence, why it possesses macro- and histopathological features of both. A potentially aggressive skin cancer with metastatic potential.

A basosquamous lesion on the face

Image courtesy of PD. Klaus via Wikipedia Commons

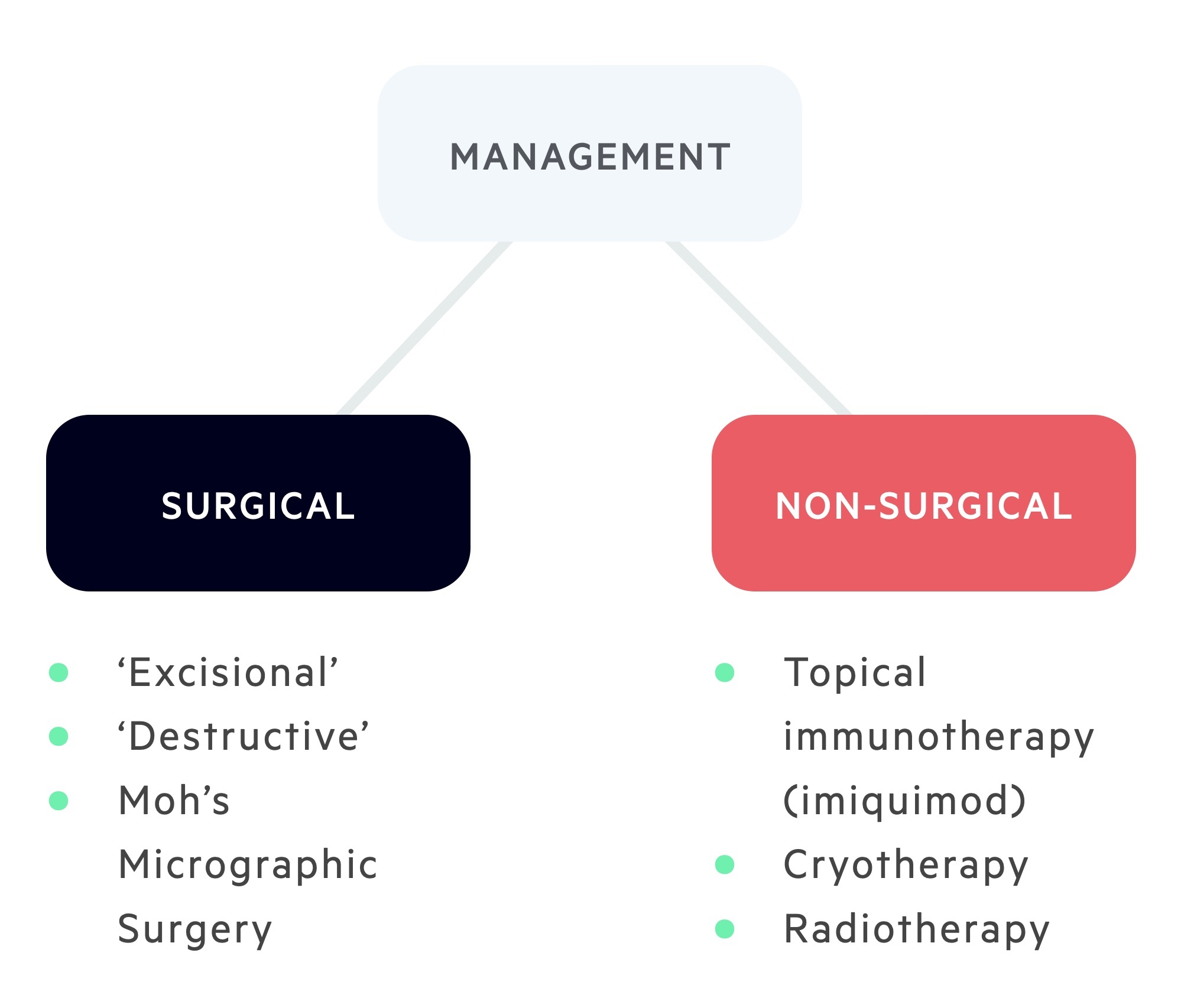

Management

Management may be surgical or non-surgical and based upon a clinical-suspicion (e.g. what the lesion looks like) or upon a biopsy result (tissue diagnosis).

Surgical treatment may be ‘Excisional’ or ‘Destructive’:

- ‘Excisional’ – e.g, wide-local excision (common treatment modality) or Moh’s Micrographic Surgery (typically reserved for high-risk lesions)

- ‘Destructive’ – e.g. curettage and cautery, cryotherapy or carbon dioxide laser. NB – these methods do not provide a histological sample, therefore they are typically reserved for low-risk lesions only.

Non-surgical treatment:

- Radiotherapy, may be used in:

- Adjuvant therapy

- Prevention of reoccurrence (e.g. incompletely excised margins)

- Recurrent BCCs

- High-risks BCCs (where surgery is not appropriate)

- NB – there is a risk of radiation-induced BCC development in patients with Gorlin’s syndrome!

- Topical immunotherapy (Imiquimod)

- PDT (Methyl aminoevulinate MAL-PDT)

High vs. Low-risk lesions

A high-risk BCC is determined by ANY of the below:

- Size > 2 cm

- Site (around eyes, nose, lips and ears)

- Poorly-defined margins

- Histological sub-type (morpoeic, infiltrative, micronodular, basosquamous)

- Histological features (e.g. perineural / perivascular invasion)

- Previous treatment failure

- Immunosuppression

Treatment selection

Generally speaking, treatments that do not permit histological confirmation (tissue diagnosis) are only used for LOW RISK lesions.

Consider patient, tumour and practitioner factors:

- Patient – choice, co-morbidities, anti-coagulants etc.

- Tumour – high vs. low risk

- Practitioner – preference, experience, availability

Surgical excision margins

Surgical excision margins are based upon the British Association of Dermatologists (BAD) guidelines for BCC.

Lesions should be excised down to subcutaneous fat to ensure that the entirely of skin (epidermis and dermis) has been included in the excision sample.

- Low-risk lesions (small <2 cm, well-defined) – 4-5 mm margin provides 95% clearance.

- High-risk lesions (large >2cm, poorly-defined) – 5 mm margin provides 82% clearance; consider referral for Moh’s Surgery.

- Recurrent lesions – referral to Skin MDT; re-excision of scar (5-10 mm margins) or Moh’s Surgery +/- Radiotherapy.