Overview

Septic arthritis is an infection of one or more joints.

Bacterial infection is by far the most common cause of septic arthritis with staphylococcus aureus most frequently isolated. It normally presents with pain and swelling of the affected joint with signs of systemic infection. The condition may be categorised as:

- Native joint infection: infection affecting a native joint, management typically requires joint drainage (where appropriate) and antimicrobial therapy.

- Prosthetic joint infection (PJI): a serious complication of prosthetic joint replacement. Surgical intervention in addition to antimicrobial therapy is commonly required.

Septic arthritis requires prompt recognition and management. Untreated it can lead to articular destruction and overwhelming sepsis. This note focuses on the condition in adult patients.

Epidemiology

Septic arthritis is rare, it has an estimated incidence of 4-10 per 100,000 patient-years in Western Europe.

It most commonly affects the extremes of age (children and the elderly). It is also more common in those with immunodeficiency or IV drug use.

The rate of prosthetic joint infection varies depending on the joint. The two most common joint replacements in the UK are the knee and hip. Knee arthroplasty (approx 0.5-2%) is more commonly affected by septic arthritis than the hip (approx 0.5-1%)

Microbiology

Identifying the underlying organism and resistance pattern is key to the management of septic arthritis.

Bacteria are by far the most common pathogen responsible for septic arthritis. The causative organisms vary depending on age, though staphylococcus aureus is the most common cause in all groups above the age of 2.

Gram-positive bacteria

Staphylococcus aureus is a gram-positive cocci and the most common cause of septic arthritis in adults (accounting for 35-56% of cases) and children above the age of 2. There is increasing incidence of methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), particularly in the intravenous drug user (IVDU) and elderly populations.

Streptococcal species (gram-positive cocci) are the second most commonly isolated organisms in most research series. This Includes streptococcus pyogenes and group B streptococci.

Gram-negative bacteria

Neisseria gonorrhoeae, a gram-negative diplococci, is a common cause of septic arthritis, particularly in young, sexually active individuals. Neisseria meningitidis another gram-negative diplococcus may also cause the disease.

Gram-negative rods including E.coli and Klebsiella may be isolated. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is most commonly seen in IVDU.

Pathophysiology

Septic arthritis arises when bacteria (or other pathogens) enter the synovium.

Mechanism of infection

Haematogenous spread is the most common mechanism by which bacteria infect the joint. Bacteria in the bloodstream seed into a joint and infection results.

Direct inoculation can occur during surgery, secondary to animal bites, wounds or rarely joint injection. Spread can also occur due to the spread from neighbouring infective foci.

Pathogenesis

The synovium is a specialised membrane that is well vascularised and lacks a basement membrane. The lack of a limiting basement membrane makes it susceptible to infection.

Bacteria colonise the synovial fluid and an inflammatory response is generated. In immunocompetent patients, the immune response may eliminate the pathogen and clear the infection. If the infection continues, inflammation leads to worsening joint effusion with a resulting rise in the intra-articular pressure impairing the vascular supply. Untreated, infection becomes systemic and joint destruction occurs.

Prosthetic joint infection

Prosthetic joint infection (PJI) represents an uncommon but serious complication of surgery.

PJI occurs in around 0.5-1% of hip replacements and 0.5-2% of knee replacements. If it occurs it commits the patient to long courses of antibiotics, further surgical intervention and often lengthy hospital stays.

The presence of foreign material enhances certain bacteria’s ability to form a biofilm. This protective layer causes a significant reduction in the chance of successful elimination of infection with antibiotics alone.

The timing of infection can give an indication to the causative pathogen and mechanism of infection:

- Early (< 3 months): normally acquired during surgery or following early wound breakdown. The presentation is typically acute with a warm, red, painful and swollen joint accompanied by signs of systemic infection. Staphylococcus aureus and gram-negative rods are often implicated.

- Delayed (3-12 / 24 months): often acquired during surgery, these infections tend to present with more insidious features of mild pain, joint swelling and malaise. Less virulent agents like coagulase-negative staphylococci and propionibacterium acnes are implicated.

- Late (> 12 / 24 months): these infections are more likely to be unrelated to the original operation, instead, arising from haematogenous spread. They often present acutely similar to the description of early infections above, signs of a central source of infection may be present (e.g. infective endocarditis). Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus spp., gram-negative rods and anaerobes are often implicated.

Risk factors

Septic arthritis is more frequently seen in elderly diabetic patients.

- Diabetes

- Advancing age

- Prosthesis

- Immunodeficiency / immunosuppression

- IV drug abuse (consider resistant organisms and pseudomonas)

Clinical features

A high index of suspicion should be had for any patient presenting with acute atraumatic joint pain.

Patients present with an acutely swollen, warm and painful joint – signs of systemic infection may be present. Septic arthritis is normally monoarticular, though polyarticular disease is seen.

Some will present with more subtle and insidious features – in these patients pain and swelling may be mild and signs of systemic infection absent.

Symptoms

- Pain

- Swelling

- Fevers

- Inability to weight bear

Signs

- Pain on active and passive movement

- Reduced ROM (range of motion)

- Erythema

- Warmth

- Joint effusion

Differential diagnosis

A number of conditions may present with a similar clinical picture. Excluding septic arthritis is essential.

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Osteoarthritis

- Crystal arthropathies (gout, pseudogout)

- Drug-induced arthritis

- Haemarthrosis

- Reactive arthritis

- Lyme disease

Investigations

Joint aspiration is key and should be obtained prior to antibiotics (whenever possible).

Blood tests will normally show an elevated CRP and white cell count indicative of inflammation and infection, though these are non-specific changes seen in other infections and inflammatory conditions (e.g. gout). Observations frequently show pyrexia that may be accompanied by tachycardia, on occasion haemodynamic instability is present.

Joint aspiration is the gold standard for diagnosis – where possible taken prior to antibiotic therapy. Imaging, particularly MRI, can be supportive for a diagnosis of septic arthritis.

Bedside

- Vital signs

- Blood sugar

- Urine dip / MSU

- Consider sexual health screen

Bloods

- FBC

- U&Es

- CRP

- LFTs

- ESR

- Urate (often sent but of little diagnostic value in acute gout or septic arthritis)

- Blood cultures

- Lyme serology (if indicated)

Imaging

- Plain radiograph: useful to exclude missed fracture. May show features consistent with septic arthritis such as evidence of joint swelling, soft tissue oedema and periarticular osteomyelitis. Evidence of other conditions such as chondrocalcinosis in pseudogout may be seen.

- USS: may be used, particularly to demonstrate joint effusions (perhaps more commonly in children). Can also be used to help to guide joint aspiration.

- CT/MRI: offers diagnostic information, can give evidence of complications such as osteomyelitis and periarticular abscesses.

Special

- Joint aspiration: the most important investigation. Joint fluid should be obtained prior to commencing antibiotics. It should be sent for WBC, gram stain, culture and crystal microscopy (to exclude gout/pseudogout).

- Synovial tissue culture: may be taken during arthroscopy, particularly useful when fungal infections or tuberculosis are suspected.

Sepsis six

All patients with suspected sepsis should be managed with the sepsis six care bundle.

Any patient with suspected sepsis should be managed with the SEPSIS-6 principles in mind. The sepsis six bundle is a protocol by which a patient may be investigated and treated for sepsis. It is by no means exhaustive but incorporates key investigation and treatment points. The bundle should be initiated and completed within one hour of recognition of the signs. All patients with significant infection should have a senior review. Further support may be required including vasopressors (e.g. noradrenaline) to maintain blood pressure, given in AE resus or ITU.

It is imperative, (where possible) in the case of suspected septic arthritis, that joint aspirations are obtained prior to antibiotics.

Three In

Patients should receive high flow oxygen to achieve appropriate target saturations. A target of 94-98% is appropriate for the majority of patients. Those at risk of carbon dioxide retention (COPD) should have a target of 88-92%. IV fluids should be started, often 500ml of crystalloid over 15 minutes with reference to the patient’s haemodynamic status and co-morbidities. Antibiotics are key and should be given without delay, refer to local guidelines/microbiology advice.

Three out

A minimum of two sets of blood cultures should be taken. Ideally, this should happen prior to administration of antibiotics though they should not be a cause for delay. Additionally, in cases of septic arthritis, joint fluid samples should be obtained wherever possible. A serum lactate should be obtained normally via a blood gas (arterial or venous) to help assess the patient’s status. Urine output should be measured ideally with a catheter with a careful fluid balance recorded.

Management

Patients with septic arthritis should be referred to and managed by orthopaedics.

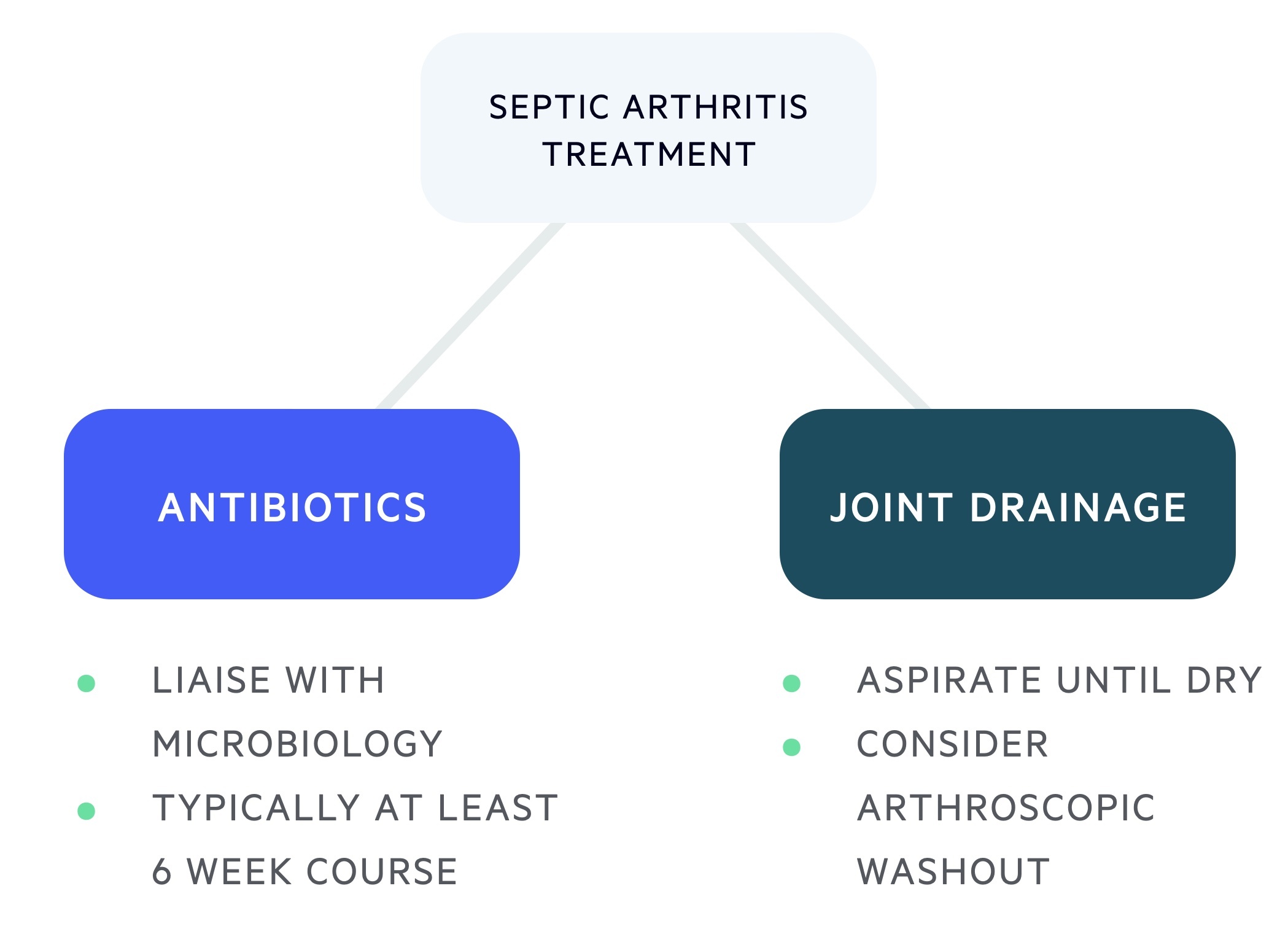

Antibiotics

Antibiotic management should be guided by patient factors, the suspected organism and culture results. Liaise with microbiology early. Typical courses last six weeks, with at least two weeks of intravenous therapy.

Gram-negative bacteria are more common in the elderly and those suffering with recurrent UTIs. MRSA should be considered in patients with risk factors such as known MRSA colonisation or long lines (e.g. CVC).

There is no single set of antimicrobial guidelines, clinicians should refer to their local protocols. Flucloxacillin is frequently first-line therapy (clindamycin if penicillin-allergic). Vancomycin or teicoplanin are used in cases of suspected MRSA and ceftriaxone for gonococcal arthritis or suspected gram-negative infections.

Patients with PJI require joint specialist input from orthopaedic surgery and microbiology. IVDU, immunosuppressed and ITU patients should be treated with close coordination with the microbiology team.

Joint drainage

The septic joint should be aspirated to dryness, this may be repeated if required.

Arthroscopic drainage and washout should be considered. Complex interventions may be required for patients with a prosthesis, this should be determined by senior orthopaedic surgeons.

Prognosis

The mortality from septic arthritis is estimated to be around 11%.

Joint destruction is thought to result in loss of function in around 40% of patients – this is dependent on the pathogen and the period between onset and treatment.

As a relatively rare condition, a great deal of variety is seen in the published figures. Mortality is higher in IV drug users and those with significant co-morbidities.