Overview

Radiculopathy refers to symptoms or impairments related to the involvement of a spinal nerve root.

The spinal nerve roots serve as the main communication between the central nervous system (i.e. the spinal cord) and the peripheral nerves. When a spinal nerve root is affected, it is known as radiculopathy.

Radiculopathies may be single or multiple. When multiple nerve roots are affected it is known as polyradiculopathy. The symptoms of radiculopathy are usually characteristic because each root supplies a specific area of cutaneous tissue, known as the dermatome, and a functional group of muscles, known as a myotome. Therefore, patients typically present with radicular pain and/or sensory changes in the distribution of the dermatome with or without impairment of muscle function within the myotome.

Radiculopathies can be categorised by the type of nerve roots affected within the spine:

- Cervical radiculopathies (C1-C8)

- Thoracic radiculopathies (T1-T12)

- Lumbosacral radiculopathies (L1-S3): by far the most common

Dermatomes and myotomes

Each spinal nerve root carries out important sensory/motor functions along a specific distribution.

The spinal nerve roots serve as the main communication between the central nervous system (i.e. the spinal cord) and the peripheral nerves. The spinal cord ends at the L1/L2 vertebrae and is divided into four main regions termed cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral. These regions are further divided into 31 spinal cord segments. Arising from the 31 spinal cord segments are the paired ventral and dorsal spinal nerve roots, which join to form the 31 paired spinal nerves (8 cervical, 12 thoracic, 5 lumbar, 5 sacral, 1 coccygeal).

Damage or impingement of a spinal nerve or root is known as radiculopathy. Each spinal nerve root carries out important sensory/motor functions along a specific distribution. These are known as myotomes and dermatomes:

- Myotome: a collection of muscles innervated by a single spinal nerve root

- Dermatome: an area of skin supplied by a single spinal nerve root

Dermatomes

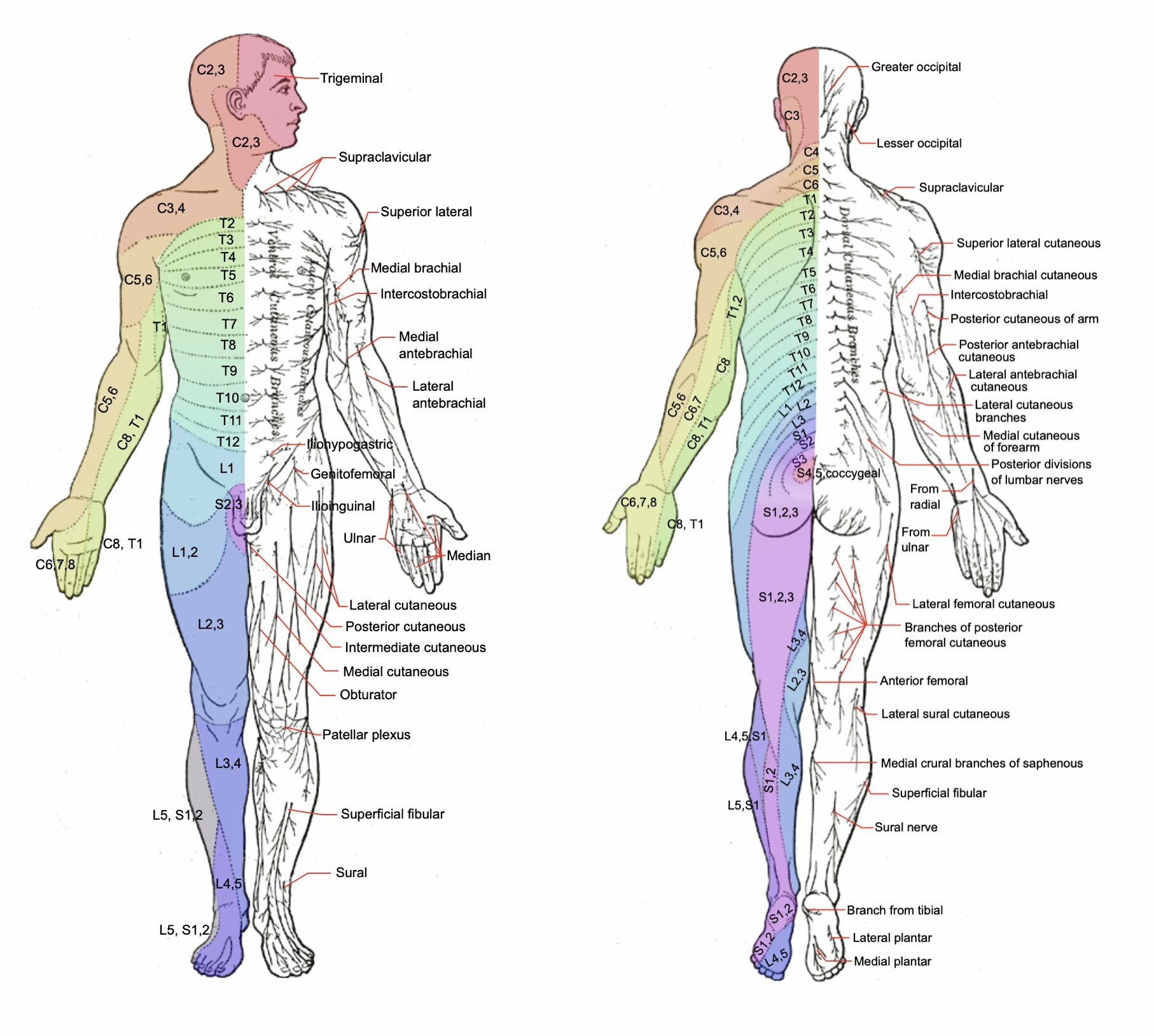

A dermatome simply refers to an area of skin supplied by sensory nerves that are derived from a single spinal nerve. They are essentially a cutaneous map of spinal nerve innervation that is broadly similar across individuals. Sensory symptoms within a particular dermatome help localise the suspected radiculopathy.

The dermatomes are best visualised through an image of the human body.

Dermatome map in posterior and anterior view (C2-S4/5)

Labels refer to cutaneous sensory branches of peripheral nerves

Myotomes

A myotome simply refers to a group of muscles supplied by a single spinal nerve. There are several important myotomes to remember of the upper and lower limb, which are listed below:

- C4: shoulder elevation

- C5: shoulder abduction

- C6: elbow flexion

- C7: elbow extension

- C8: thumb extension

- T1: finger adduction

- L1/L2: hip flexion

- L3: knee extension

- L4: ankle dorsiflexion

- L5: great toe extension

- S1: ankle plantar flexion

NOTE: this is an oversimplification of the myotomes and nerve roots may have overlapping functions (e.g. L2 assists in hip flexion, knee extension, and hip adduction).

Aetiology and pathophysiology

Degenerative spinal disease is commonly implicated in radiculopathies.

Degenerative changes in the spine are commonly the cause of impingement of the spinal nerve roots leading to clinical features consistent with radiculopathy. Changes to the intervertebral discs or zygapophyseal (facet) joints are the most likely structures involved.

Importantly, degenerative changes in the spine known as ‘spondylosis’ are common as people age. These may cause non-specific low back pain. This does not mean a patient has a radiculopathy or ‘sciatica’. When there are degenerative spondylotic changes affecting the nerve root(s) this is considered a radiculopathy and characterised by radicular pain that is often referred to as ‘sciatica’ (discussed more below).

There are two broad causes of radiculopathies:

- Skeletal: most commonly degenerative spondylotic changes in the intervertebral discs and facet joints

- Non-skeletal: a variety of causes including infection, vasculitis, inflammation, and neoplasia

Skeletal

The spine is formed by 33 vertebrae that are joined together by intervertebral joints. These include two major areas:

- Joints at the vertebral bodies: between each vertebral body is an intervertebral disc composed of a central nucleus pulposus and surrounding annulus fibrosus

- Joints at the arches: between superior and inferior articular processes of the vertebrae are facet joints. These are a type of synovial joint that provide stability and allow movement

The spine has several other joints depending on the location (e.g. Craniovertebral) and several important ligamentous structures to provided stability.

Damage to the facet joints (commonly due to arthritis) can lead to hypertrophy and the formation of small boney outgrowths known as osteophytes. These can lead to impingement of the spinal roots and subsequent radiculopathy. Alternatively, disruption of the facet joint by spondylosis can lead to misalignment of the spine and instability. If the misalignment affects the spinal nerves roots it will lead to radiculopathy and if it affects the spinal cord it will lead to myelopathy.

Damage to the intervertebral discs can lead to disc herniation and impingement of the spinal cord or spinal nerve roots. Herniation refers to the rupture of disc material (i.e. nucleus pulposus) beyond the annulus fibrosus. In fact, it is suggested that age-related change in the nucleus pulposus within the intervertebral disc is what precipitates major degenerative changes in the spine including disc herniation, disc collapse, spondylosis, and spinal instability.

Commonly there is an ‘inciting event’ such as a fall, bending over, vacuuming or trauma.

Non-skeletal

A variety of non-skeletal causes of radiculopathy exist, which can be divided into several broad categories:

- Diabetes mellitus

- Infections: Lyme disease, Epstein-Barr virus, Herpes simplex virus, Varicella Zoster virus

- Inflammatory conditions: Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (a variant of GBS also involving the spinal nerves), chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (a variant of CDIP also involving the spinal nerves)

- Vascular: arteriovenous malformation, vasculitis

- Mass lesion or neoplasia: epidural abscess, metastasis, intradural tumour (e.g. meningioma), myeloma, lymphoma

Lumbosacral radiculopathies

Lumbosacral radiculopathy refers to damage or dysfunction of one or more lumbosacral nerve roots.

In clinical practice, the most common radiculopathies are those affecting the lumbosacral nerves between L1-S4. It is thought to affect up to 5% of the general population with an equal sex prevalence. They typically cause radicular pain in the distribution of the spinal nerve root that occurs with or without myotome weakness. Diagnosis is confirmed on imaging (e.g. MRI).

Aetiology

The typical cause of lumbosacral radiculopathies is a degenerative disease of the spine (e.g. spondylosis of the facet joints, disc herniation). Other causes may include non-skeletal aetiologies including infection (e.g. Lyme disease), vascular disorders (e.g. vasculitis), and mass lesions (e.g. lymphoma, epidural abscess).

The presentation of radiculopathy may be acute in association with movement (e.g. bending, lifting) or trauma (e.g. falling). Up to 50% of lumbosacral radiculopathies are associated with an ‘inciting event’.

Clinical features

Patients with lumbosacral radiculopathy characteristically have radicular pain (i.e. pain in the distribution of the spinal nerve root dermatome) alongside other sensory symptoms including paraesthesia or anaesthesia (i.e. sensory loss). Muscle weakness may be present that corresponds to the affected myotome but this may only be apparent on clinical examination.

The classic presentation for each lumbosacral radiculopathy is as follows:

- L1 radiculopathy: a rare radiculopathy. Causes sensory changes in the inguinal region, but weakness is uncommon

- L2-4 radiculopathy: discussed together because of marked overlap in symptoms. Commonly causes acute back pain that radiates around the anterior thigh. Sensory changes may be present over the anterior thigh and medial lower leg. Weakness in hip flexion, knee extension, and hip adduction can be seen. There may be a loss of the knee reflex

- L5 radiculopathy: Most common radiculopathy in this region. Commonly causes acute back pain that radiates down the lateral aspect of the leg to the foot. Sensory changes may be present over the lateral aspect of the lower leg and dorsum of the foot. Weakness is seen in foot dorsiflexion, big toe extension, and foot inversion/eversion

- S1 radiculopathy: Commonly causes acute back pain that radiates down the posterior aspect of the leg into the foot. Sensory changes may be present over the posterior leg and lateral foot. Weakness may be present in hip extension and knee flexion. There may be a loss of the ankle reflex

Several manoeuvres can be completed to determine whether the pain is radicular in origin, which includes:

- Straight leg raise for L5/S1 radiculopathy: worsening radicular pain on raising the leg with the knee extended. Pain should be relieved if the knee is flexed

- Reverse straight leg raise for L2-4 radiculopathy: worsening radicular pain on extending the leg with the patient prone

Sciatica

Sciatica is a non-specific clinical description of pain affecting the back and/or leg.

Sciatica is a commonly used clinical term that is often confused with lumbosacral radiculopathy. Sciatica is a non-specific clinical description of pain affecting the back and/or leg.

It is typically used to describe a sharp or burning pain that radiates from the buttock along the course of the sciatic nerve down the posterior/lateral leg and usually to the foot or ankle. The sciatic nerve is formed by a combination of nerve roots L4, L5, S1, S2, and S3. Therefore, involvement of any of these nerve roots alone or in combination can cause a variety of sciatica-like symptoms otherwise known as ‘radicular pain’.

Sciatica is therefore the clinical manifestation of lumbosacral radiculopathies. However, the difficulty arises in the fact that the term is used more generally as a reference to lower back pain that may be non-radicular in origin (i.e. not caused by radiculopathy). Therefore, when a patient has ‘sciatica’ it is important to determine exactly what is meant by the term and whether there is ‘radicular’ quality to the pain.

Thoracic radiculopathies

Thoracic radiculopathy refers to damage or dysfunction of one or more thoracic nerve roots.

Thoracic radiculopathies are uncommon because the movement of the thoracic vertebrae is limited by the rib cage. This means the thoracic spine is less prone to the degenerative changes of the lumbar and cervical spine that lead to radiculopathies.

Aetiology

A variety of causes may lead to thoracic radiculopathy including diabetes mellitus, disc herniation, infections, tumours, or metastatic deposits. The development of thoracic back pain is a red flag sign and should always be taken seriously. Beware of older patients with new-onset back pain that may indicate myeloma, prostate cancer, breast cancer, and lung cancer.

Clinical features

Thoracic radiculopathy is characterised by radicular pain that starts in the back and radiates around the chest in a linear pattern. Other sensory symptoms including paraesthesia and anaesthesia (i.e. sensory loss) may be experienced in the same dermatomal distribution. Muscular weakness is less noticeable with thoracic radiculopathies. Sudden back movements or increases in thoracic pressure (e.g. Valsalva maneuvers) may precipitate radicular pain.

Cervical radiculopathies

Cervical radiculopathy refers to damage or dysfunction of one or more cervical nerve roots.

Cervical radiculopathies are characterised by neck, shoulder, and arm pain with sensory changes and weakness in the distribution of the spinal nerve. The mean age of diagnosis is the 5th decade of life and there is a slightly higher prevalence in men.

The lower cervical nerve roots are more commonly affected with up to 70% of cases due to C7 nerve root involvement and 20% C6 nerve root involvement.

Aetiology

Similar to lumbosacral radiculopathies, the majority of cervical radiculopathies are due to compressive aetiologies especially spondylosis (i.e degenerative spinal changes) and disc herniation.

Nondegenerative causes can occur including infection (e.g. varicella zoster virus), tumour infiltration, or vascular causes (e.g. vasculitis).

Clinical features

Patients with cervical radiculopathy typically present with neck, shoulder and/or arm pain in association with sensory changes and muscle weakness. Disc herniation often leads to acute symptoms whereas spondylosis causes slowly progressive features.

The classic presentation for each cervical radiculopathy is as follows:

- C5 radiculopathy: associated with pain in the neck, shoulder, and scapula. Sensory loss is usually seen in the lateral aspect of the upper arm with weakness in shoulder abduction. Biceps and brachioradialis reflexes may be affected

- C6 radiculopathy: associated with pain in the neck, shoulder, scapula, and lateral arm, forearm, and hand. Sensory loss in the lateral forearm, thumb, and finger (pointing a gun). Weakness may be seen in elbow flexion and supination/pronation. Biceps and brachioradialis reflexes may be affected

- C7 radiculopathy: associated with pain in the neck, shoulder, hand, and middle finger. Sensory loss in the palm, middle, and index finger. Weakness is usually seen in elbow and wrist extension. Triceps reflex may be affected

- C8 radiculopathy: associated with pain in the neck, shoulder, medial forearm, hand, and 4th/5th fingers. Sensory loss in the medial forearm, hand, and 4th/5th digits and weak finger movements

NOTE: T1 radiculopathy is often discussed alongside cervical radiculopathies. This is because it provides innervation through the brachial plexus and contributes to sensation and movement in the upper limb. It typically causes neck pain in association with anterior arm and medial forearm sensory loss. Weakness is usually seen with thumb abduction and finger abduction/adduction.

Several important signs may be present that are suggestive of the involvement of the cervical cord (i.e. cervical myelopathy):

- Lhermitte phenomenon: shock-like paraesthesia radiating down the spine and towards the legs that occur on neck flexion

- Gait disturbance

- Upper motor neuron signs in the lower limbs (e.g. increased tone, weakness, clonus, upgoing plantar)

- Bladder/bowel dysfunction

Several manoeuvres can be completed to determine whether the pain is radicular in origin, which includes:

- Spurling manoeuvre: positive if worsening radicular pain or paraesthesia when downward pressure is applied to the head when it is extended and rotated to the affected side. This promotes posterior disc bulging and narrows the ipsilateral neural foramina thus provoking symptoms

- Shoulder abduction relief test: positive if a decrease or disappearance of symptoms when the arm of the affected side is raised and then the hand placed on the head

Diagnosis & investigations

Neuroimaging is critical to establish the diagnosis of radiculopathy.

The principal investigations for the diagnosis of radiculopathy is neuroimaging of the spine that allows assessment of the spinal nerve roots as they leave the spinal canal and electrodiagnostic studies (e.g. electromyography and nerve conduction studies).

Neuroimaging

Neuroimaging includes both magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) of the spine. It allows assessment of the spine, intervertebral discs, spinal cord, and nerve roots. CT is excellent at looking at bones and has relatively good sensitivity for detecting disc herniation that is similar to MRI. However, MRI is much better at assessing soft tissue structures and allows the assessment of nerve roots. In addition, it does not expose the patient to ionising radiation.

Given the above, MRI is typically used in the routine assessment of radiculopathies unless the patient has a contraindication. In the context of acute trauma, CT is often completed first due to it being quick and easily accessible. If the diagnosis is not clear, an MRI can be subsequently requested.

Electrodiagnostic studies

Electrodiagnostic studies include both electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction studies (NCS).

- EMG (evaluates muscle units): this refers to an assessment of the electrical activity of muscles. It can assess activity during rest and voluntary contraction. Records the electrical potentials generated in a muscle belly through the insertion of a needle

- NCS (evaluates peripheral nerves): this refers to an assessment of individual peripheral nerve function. It essentially involves activating nerves electrically over several points on the skin of the upper/lower limbs and measuring the response. The test involves assessing both the size (i.e. amplitude) and speed (i.e. velocity) of signals through motor and sensory fibres

These tests are most useful in patients with more long-standing radiculopathy (at least > 3 weeks) with evidence of weakness. This enables localisation of the weakness to a spinal nerve root.

Management

The treatment of radiculopathies is highly specialised and depends on the underlying cause.

The management of radiculopathies depends on the location (e.g. lumbar versus cervical), acuity (e.g. acute versus chronic), underlying aetiology (e.g. degenerative spine disease versus vasculitis), and co-morbidities of the patient (e.g. young versus frail). It is a highly complex area, but we discuss some of the common principles below.

Non-surgical

Radiculopathies can be disabling, limiting a patient’s functional abilities, and associated with significant pain. Therefore, analgesia including neuropathic pain medications and input from the physiotherapists is essential. In patients who do not need surgery, radiculopathies may improve spontaneously with conservative measures.

Non-surgical options to consider include:

- Optimise simple analgesia: paracetamol and NSAIDs (if no contraindications) form the cornerstone of initial analgesic management. Should be offered to all patients with pain, particularly with acute radiculopathy. Opioids should be avoided where possible

- Neuropathic agents: neuropathic pain medications may be used, particularly with patients who have chronic disabling symptoms not responsive to simple analgesia. Options may include gabapentin or pregabalin

- Glucocorticoids: occasionally used in acute or severe radiculopathy as a short-term treatment to improve pain

- Activity modification: avoid activities that exacerbate pain and modify normal daily activities as appropriate

- Physiotherapy: often tried in patients with persistent mild-to-moderate symptoms. A range of exercises may be employed. The exact timing to offer therapy depends on the location and acuity. In addition, patients with severe symptoms are often unable to participate

In patients with non-compressive aetiologies (e.g. infection, vasculitis) it is important to treat the underlying cause that may involve pharmacological agents.

Surgical

Surgery in degenerative spinal disease leading to radiculopathy may be offered to patients with progressive neurological impairment or persistent severe symptoms despite non-surgical treatments. The exact timing and type of surgery are beyond the scope of these notes, but options may include:

- Open discectomy or microdiscectomy

- Disc fusion

- Laminectomy

Surgery may be indicated for other aetiologies such as epidural abscess, tumour infiltration, or metastasis.