Definition & classification

A hernia refers to an organ or part of an organ that protrudes outside the walls of its usual cavity.

Hernias may be described as:

- Reducible: the hernia may be completely returned into its original cavity.

- Irreducible: the hernia cannot be completely reduced, typically secondary to adhesions between the hernia and hernial sac (incarcerated).

- Strangulated: constriction of the hernia results in impaired circulation. These hernias represent a surgical emergency.

Inguinal hernias refer to protrusions in the inguinal or scrotal region. They are a common surgical pathology, responsible for over 60,000 procedures in England in 2011/12. Men are nine times more likely to be affected than women.

There are two types of inguinal hernia:

- Direct: the hernia protrudes through the posterior wall of the inguinal canal.

- Indirect: the hernia protrudes through the deep inguinal ring and into the inguinal canal (most common).

Aetiology & pathophysiology

The two most important factors for the development of a hernia is inherent or acquired weakness and increased pressure.

Inguinal hernias are more likely to occur at areas with an inherent or acquired weakness.

Raised intra-abdominal pressures promotes the formation of hernias through the abdominal wall. As such, they may be associated with constipation, chronic cough (e.g. COPD) and pregnancy.

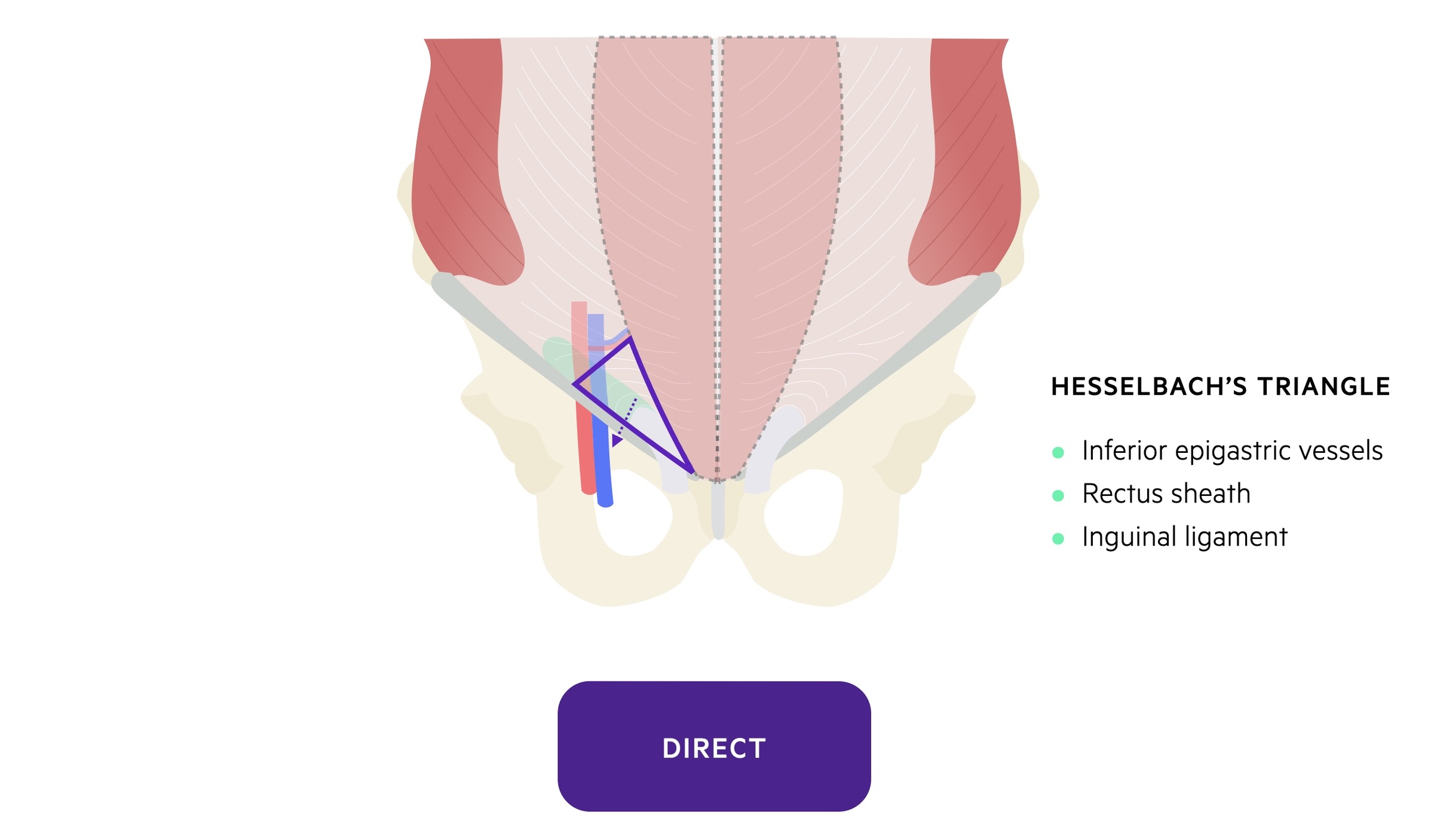

Direct inguinal hernias

Direct inguinal hernias rarely strangulate due to the wide neck through which they tend to protrude.

Direct inguinal hernias protrude through acquired defects in the posterior wall of the inguinal canal. This occurs in an area termed Hesselbach’s triangle.

Hesselbach’s triangle is found at the inferior aspect of the anterior abdominal wall. It is bounded by three structures:

- Laterally: inferior epigastric vessels.

- Inferiorly: inguinal ligament.

- Medially: lateral border of the rectus sheath.

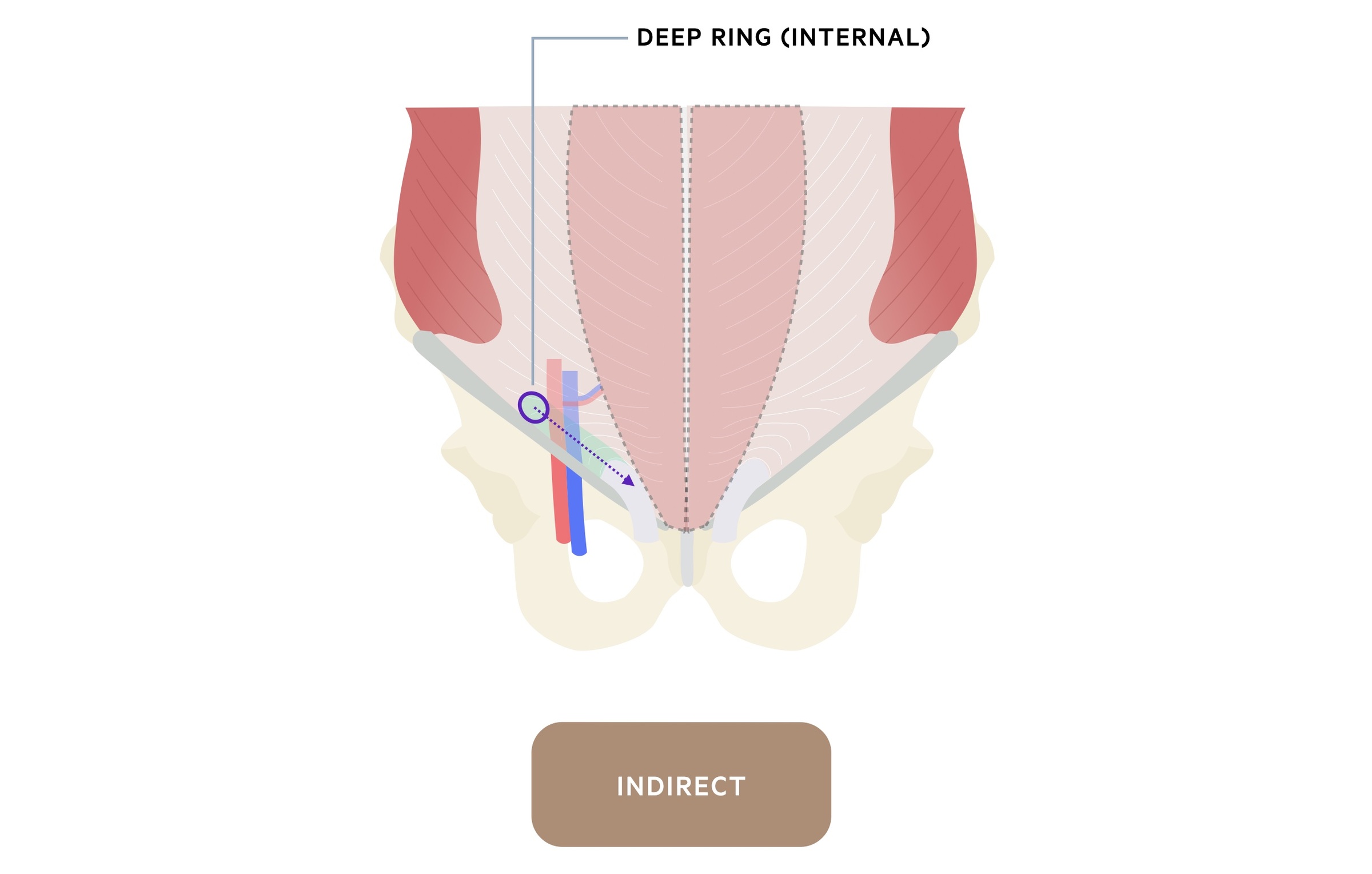

Indirect inguinal hernias

Indirect inguinal hernias are at greater risk of strangulation due to the narrow deep inguinal ring through which they protrude.

Indirect inguinal hernias exit the abdominal wall via the deep inguinal ring. They may pass through the entirety of the inguinal canal and protrude anywhere along its length or into the corresponding testicle.

A proportion of indirect inguinal hernias are congenital in nature. They develop due to a patent processus vaginalis and are more common in younger males.

The processus vaginalis is an out-pouching of parietal peritoneum that runs into the inguinal canal and normally closes naturally. A patent processus vaginalis predisposes patients to both indirect inguinal hernias and hydroceles.

Others may acquire an indirect inguinal hernia in the absence of a patent processus vaginalis.

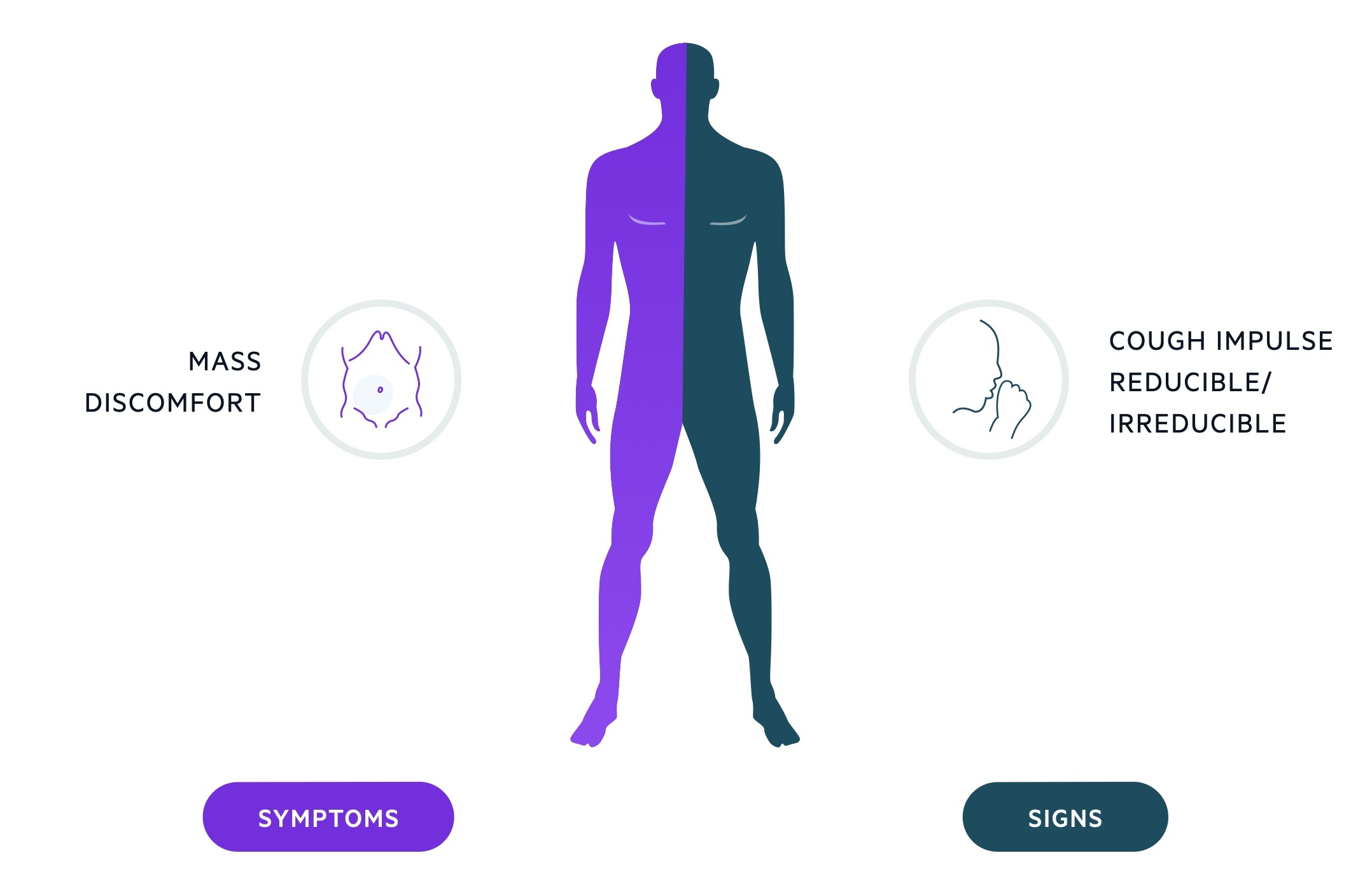

Clinical features

Patients present with a mass and discomfort in the groin .

The mass may only be present during activities that raise intra-abdominal pressures (e.g. coughing, heavy-lifting), positional or present at all times. Many patients will complain of discomfort or a dragging sensation in the groin area.

It is key that the physician establishes whether the hernia is reducible or irreducible and whether there are signs of strangulation or obstruction.

Symptoms

- Bulge or mass in groin

- Discomfort

- Dragging sensation

Signs

- Bulge or mass in groin

- Cough impulse

- Reducible or irreducible

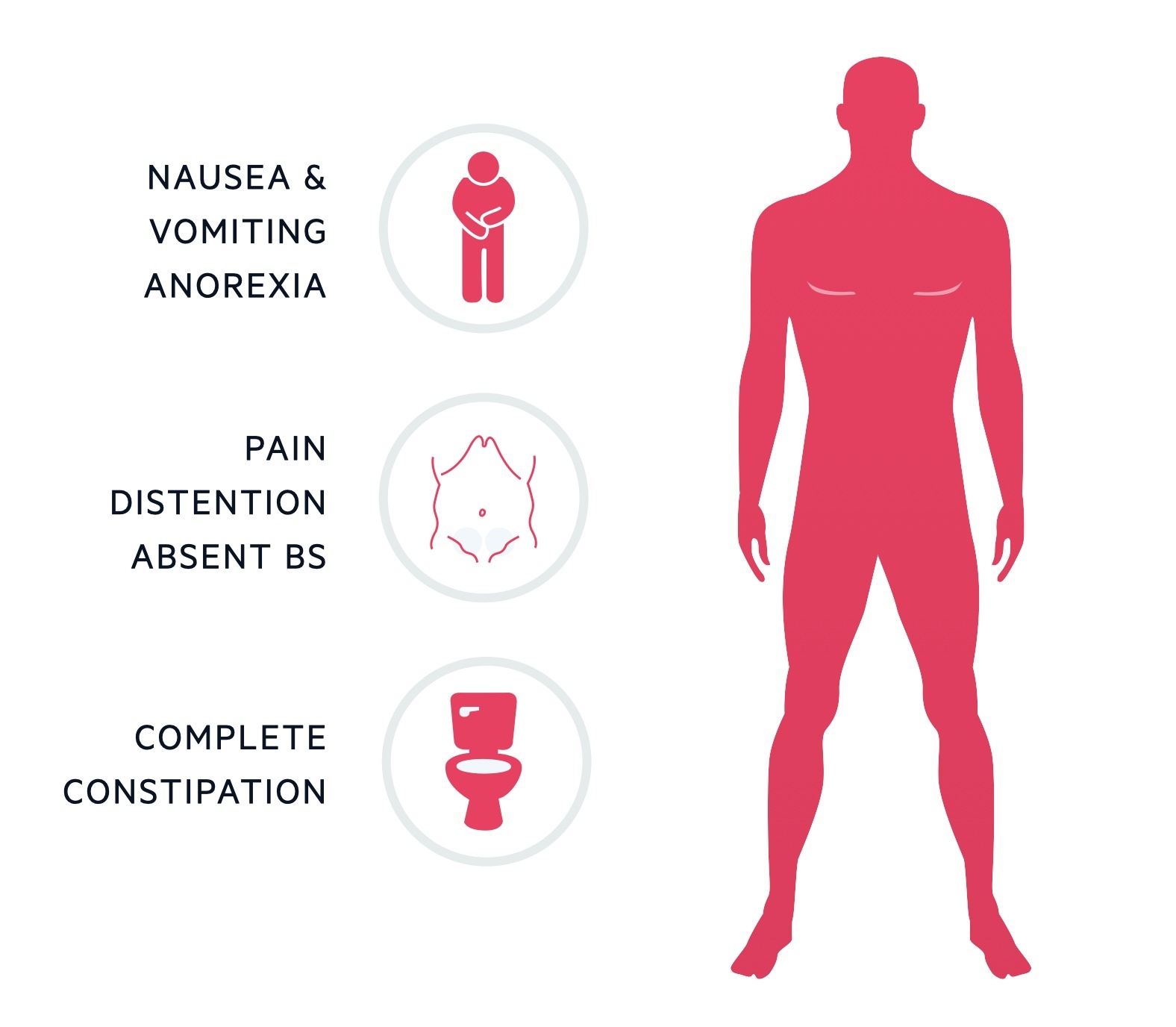

Intestinal obstruction

- Nausea and vomiting

- Abdominal pain

- Abdominal distentions

- Absent bowel sounds

- Complete constipation

Strangulation

- Above signs of obstruction

- Tender hernia

- Severe pain

- Gangrenous mass

Investigations

An inguinal hernia is traditionally a clinical diagnosis, although imaging can be used to aid the diagnosis and look for alternative pathology.

Bedside

- Observations

- ECG (pre-op work-up)

Bloods

- FBC

- UE

- CRP

- Clotting

- Group & Save

Imaging

- USS: if there is diagnostic uncertainty, USS normally confirms or excludes the presence of a hernia.

- CT: may be used for diagnosis, more commonly completed in patients presenting with complications (e.g. obstruction, strangulation).

- MRI: normally used to investigate for other causes of symptoms e.g. ‘sports hernia’.

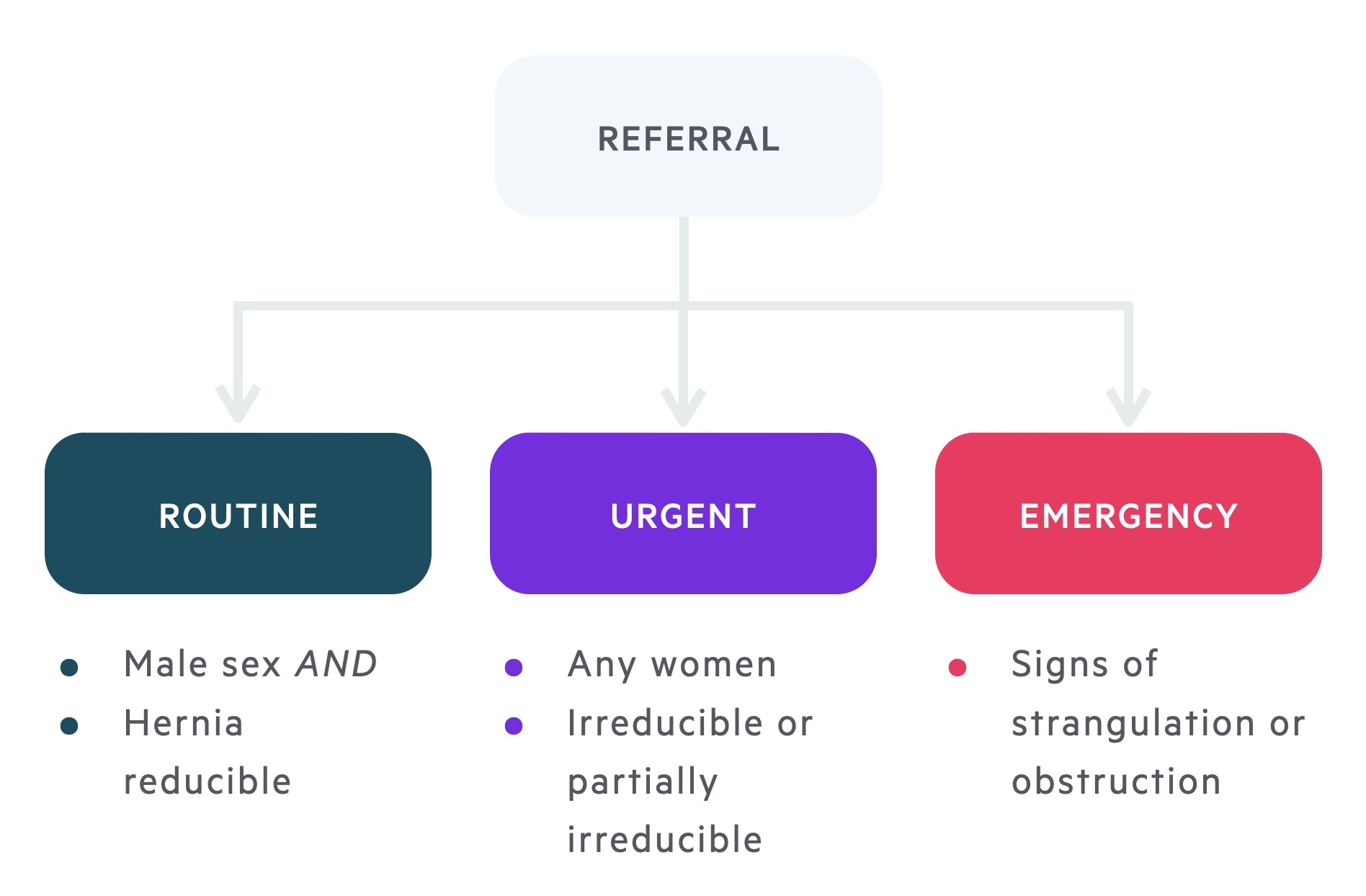

Referral

All patients with symptomatic inguinal hernias should be referred for operative management.

Non-operative management

Asymptomatic inguinal hernias can be managed conservatively with watchful waiting.

In asymptomatic cases a discussion should be had regarding elective surgery and watchful waiting. All patients, including those with symptomatic or incarcerated hernias can decline surgery if it is their wish – appropriate explanation of the risks must be given.

If the decision is made to observe, the need for surgery in the future should be explained. They should also be educated on the signs and symptoms of an irreducible hernia, bowel obstruction and strangulation.

Operative management

Operative management may be via open or laparoscopic surgery.

Hernia repairs may take one of three forms:

- Herniotomy: contents reduced and hernial sac removed. Typically used in children with congenital patent processus vaginalis.

- Herniorrhaphy: combines a herniotomy with repair of the posterior inguinal wall.

- Hernioplasty: combines a herniotomy with the insertion of a mesh to reinforce the posterior inguinal wall.

Open repair

There are several options for open surgical repair. These include the Lichtenstein tension free mesh, Shouldice and McVay repair.

The open approach offers a number of advantages over a laparoscopic approach such as reduced operative time, lower costs and the ability to be completed under local anaesthetic.

As a general rule, those presenting with a complicated hernia are operated on via an open inguinal incision – this may be supplemented by laparoscopy or laparotomy when needed.

Laparoscopic repair

Laparoscopic surgery takes the form of a total extra-peritoneal (TEP) or transabdominal pre-peritoneal (TAPP) repair.

Studies indicate the incidence of post-operative acute and chronic pain is reduced with laparoscopic repair. It is preferred in bilateral cases as well as patients at high risk of chronic pain (e.g. young, active patients).

It is also advised in female patients who have increased risk of occult femoral hernia or contralateral inguinal hernia.

In general, in the event of recurrence the approach should be different to that of the primary procedure i.e. if primary operation was open, laparoscopic should be used for recurrence.