Introduction

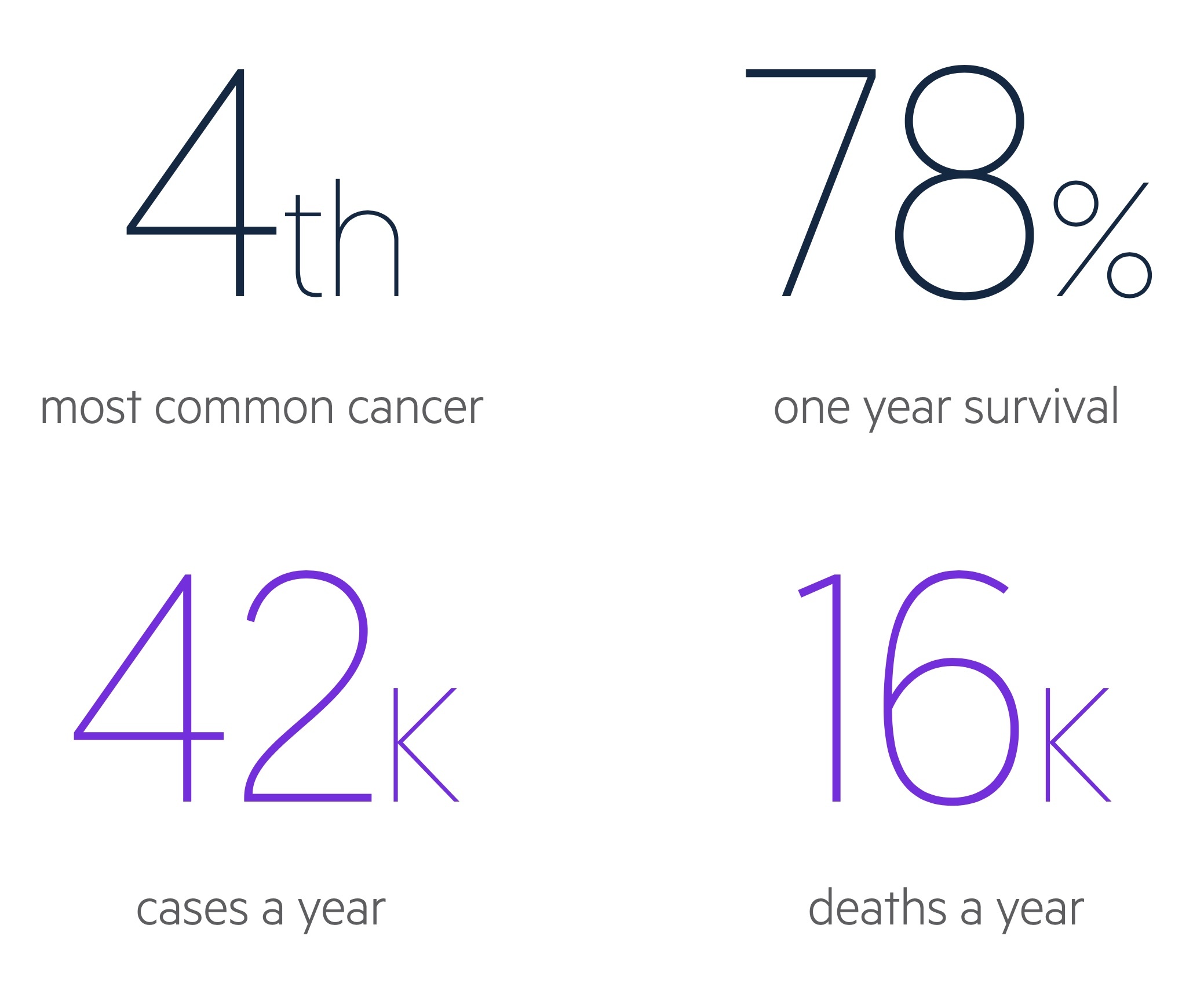

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the fourth most common malignancy in the UK and a major cause of morbidity and mortality.

It refers to malignancies that arise from the beginning of the colon, the caecum, through to the end of the rectum.

It may be found in a myriad of ways including with screening, incidentally on imaging or endoscopy, or following presentation with change in bowel habit, iron deficiency anaemia or bowel obstruction.

Management depends on staging, patient factors and patient wishes. Treatment modalities include surgical resection, metastasectomy, chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

Epidemiology

In the UK there are around 42,300 cases of colorectal cancer each year.

It is the third most common cancer in both men and women, whilst it is fourth most common overall (as a result of prostate cancer not occurring in women and breast cancer being less common in men).

CRC account for approximately 11% of malignancies in the UK. Rates generally increase with age and incidence peaks in the 85-89 age group.

Risk factors

Numerous risk factors are associated with the development of CRC.

- Family history

- Hereditary syndromes (see below)

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Ethnicity*

- Radiotherapy

- Obesity

- Diabetes mellitus

- Smoking

Dietary factors have been identified – however as with much dietary research the data is conflicting. Red meats and processed foods have been associated with the development of CRC whilst fibre has been shown to be protective.

* Figures from Cancer Research UK indicate that CRC is more common in white people than those of black or asian heritage.

Hereditary syndromes

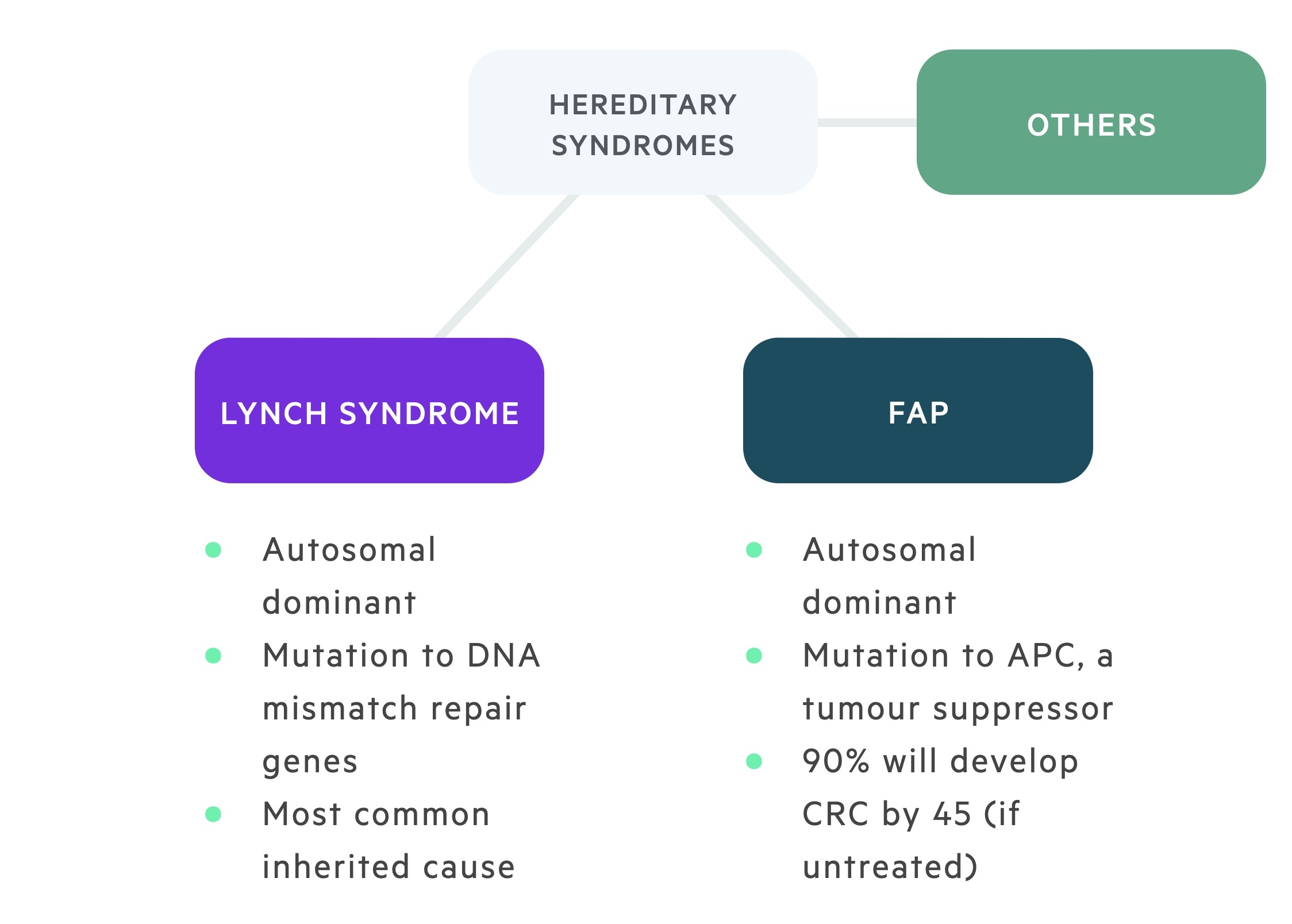

A number of hereditary syndromes increase the risk of CRC.

Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer

HNPCC, also known as Lynch syndrome, is an autosomal dominant condition responsible for around 3% of CRCs. Common mutations include MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2.

Mutations to DNA mismatch repair genes result in an increased incidence of CRC as well as a number of other malignancies including endometrial, ovarian, small bowel, gastric, gallbladder, liver, brain and renal tract.

For more on Lynch syndrome check out our notes!

Familial adenomatous polyposis

FAP is an autosomal dominant condition with penetrance approaching 100% caused by mutations to the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene – a tumour suppressor gene. It is characterised by the development of numerous adenomatous polyps in the colon and rectum, some of which undergo malignant change. 90% will develop CRC before the age of 45 if not treated. Screening is typically commenced at the age of 12-14 with an annual colonoscopy.

Prophylactic surgical resection may be offered at an appropriate time following discussion with the patient and their family. There are a number of other indications for surgery including high-grade dysplasia or a significant increase in the polyp number between colonoscopies.

Gardner syndrome is a form of FAP that also features desmoid tumours, osteomas, dental abnormalities, other lesions and an increased risk of a number of malignancies.

Others

MYH-associated polyposis: is an autosomal recessive condition characterised by colorectal adenomas and cancers caused by a mutation to MYH (MUT Y homologue) gene. MUTYH is a base excision repair gene and failure of its normal action increases the risk of colorectal cancer.

Serrated polyposis syndrome: is characterised by multiple serrated polyps. In some individuals, specific mutations have been identified but in the majority the underlying genetic cause is not understood.

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: is an autosomal dominant condition characterised by hamartomatous polyps in the gastrointestinal tract, pigmented mucocutaneous lesions and an increased risk of gastrointestinal and extragastrointestinal malignancies. Other complications include polyp-related intussusception and small bowel obstruction. There is an estimated 40% lifetime risk of colorectal cancer.

Juvenile polyposis syndrome: is an autosomal dominant condition with incomplete penetrance. It is characterised by hamartomatous polyps throughout the GI tract and an increased risk of CRC and gastric cancer.

Pathophysiology

CRC may develop via a number of pathways, the adenoma-carcinoma sequence is best described.

CRC may be considered sporadic (no clear link above the average population to family history and genetics) or inherited. Some texts and papers will also describe familial CRC – patients in whom there is family history of CRC without fitting one of the known hereditary syndromes. Sporadic CRC is responsible for around 70% of CRC, inherited 5-10% and familial 20%.

The majority of colorectal cancers are adenocarcinomas, accounting for 90-95% of cases. The colonic epithelium undergoes continuous loss and replacement and mutations may lead to abnormal developments. There are multiple pathway to malignancy though the adenoma – carcinoma sequence is common and well described.

Adenoma-carcinoma sequence

Mutations are accumulated over a number of years leading normal epithelium to develop adenomas, which become progressively more dysplastic and eventually develop into a carcinoma.

One of the earliest mutations is to the tumour suppressor adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) which leads to the hyperproliferative epithelium. One of the key mutations that follows is KRAS, a proto-oncogene, that becomes an oncogene following mutation. Further mutations to p53 (tumour suppressor and ‘guardian of the genome’) as well as SMAD4 and others leads to the development of a carcinoma from an adenoma.

This is of course a simplification of a much more complex process, but gives an idea of how multiple mutations are required to develop CRC. In inherited conditions, there are often existing mutations along this pathway (e.g. APC in FAP) that predispose individuals to CRC.

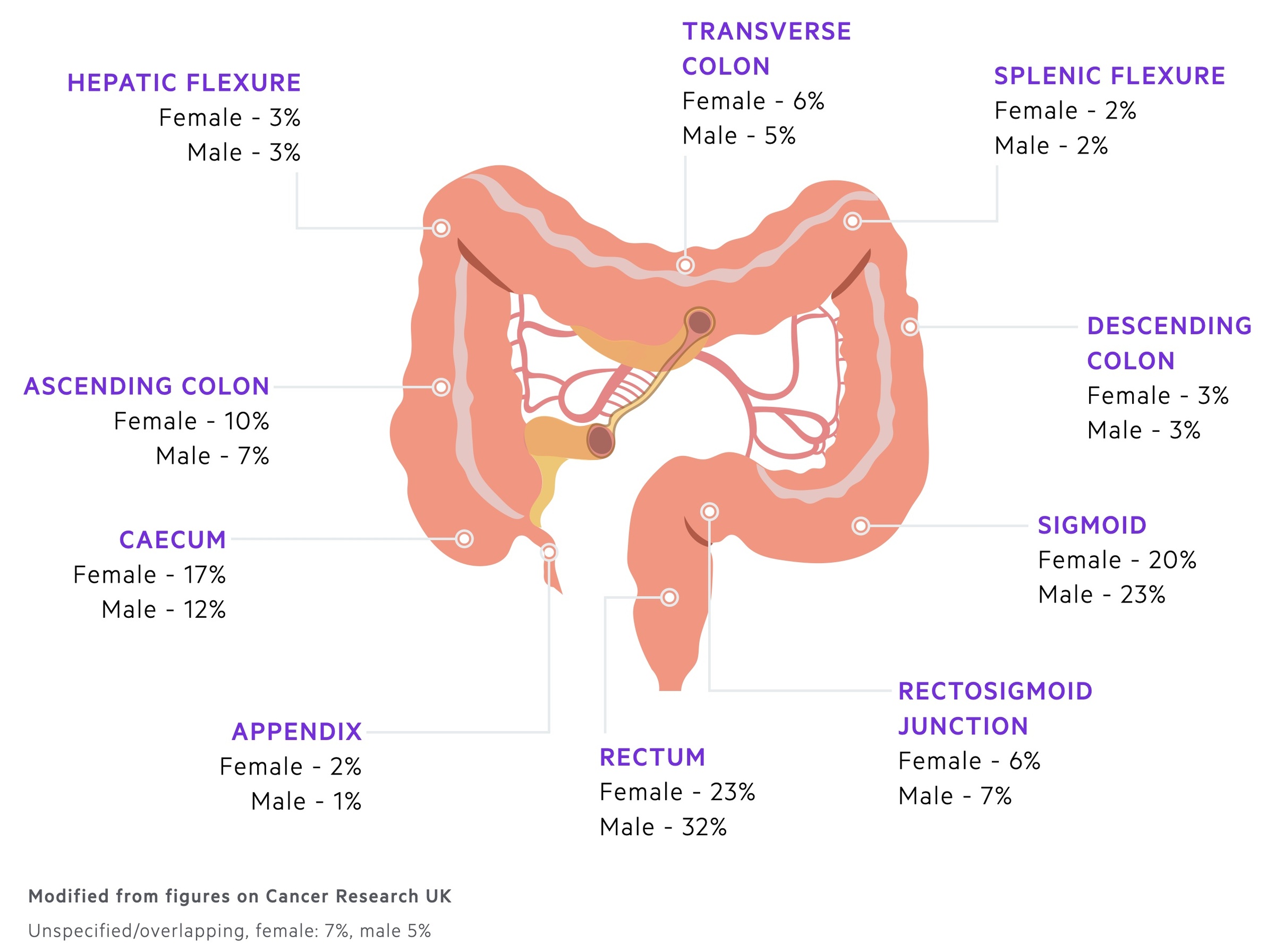

Primary sites and spread

CRC most commonly occurs in the rectum and sigmoid colon.

Primary sites

CRC may arise anywhere along the colon or rectum. Most commonly they affect the left side of the colon.

The disease develops gradually and is asymptomatic for much of its course. As such screening programmes have been introduced (see below) to try and catch the malignancy during this asymptomatic phase.

Features may be subtle and clinicians must be vigilant to pick up symptoms such as change in bowel habit and unexplained weight loss.

Disease spread

Approximately 23-26% of CRC have metastatic spread at diagnosis. The liver is the organ most commonly affected and symptoms of spread here may lead to diagnosis.

Rectal cancers are more commonly associated with lung metastasis (prior to liver metastasis) due to direct haematogenous spread via the inferior rectal vein and IVC. Other locations of metastatic spread includes the peritoneum brain and bone.

Appendiceal cancers

Appendiceal cancers are often considered separately. Most are carcinoids, though around 1 in 3 are adenocarcinoma. They may present with symptoms, be incidentally identified on imaging or be found on histology following appendicectomy.

Spread tends to be into the peritoneum. The appearance of pseudomyxoma peritonei (if mucin producing) may be seen.

Clinical features

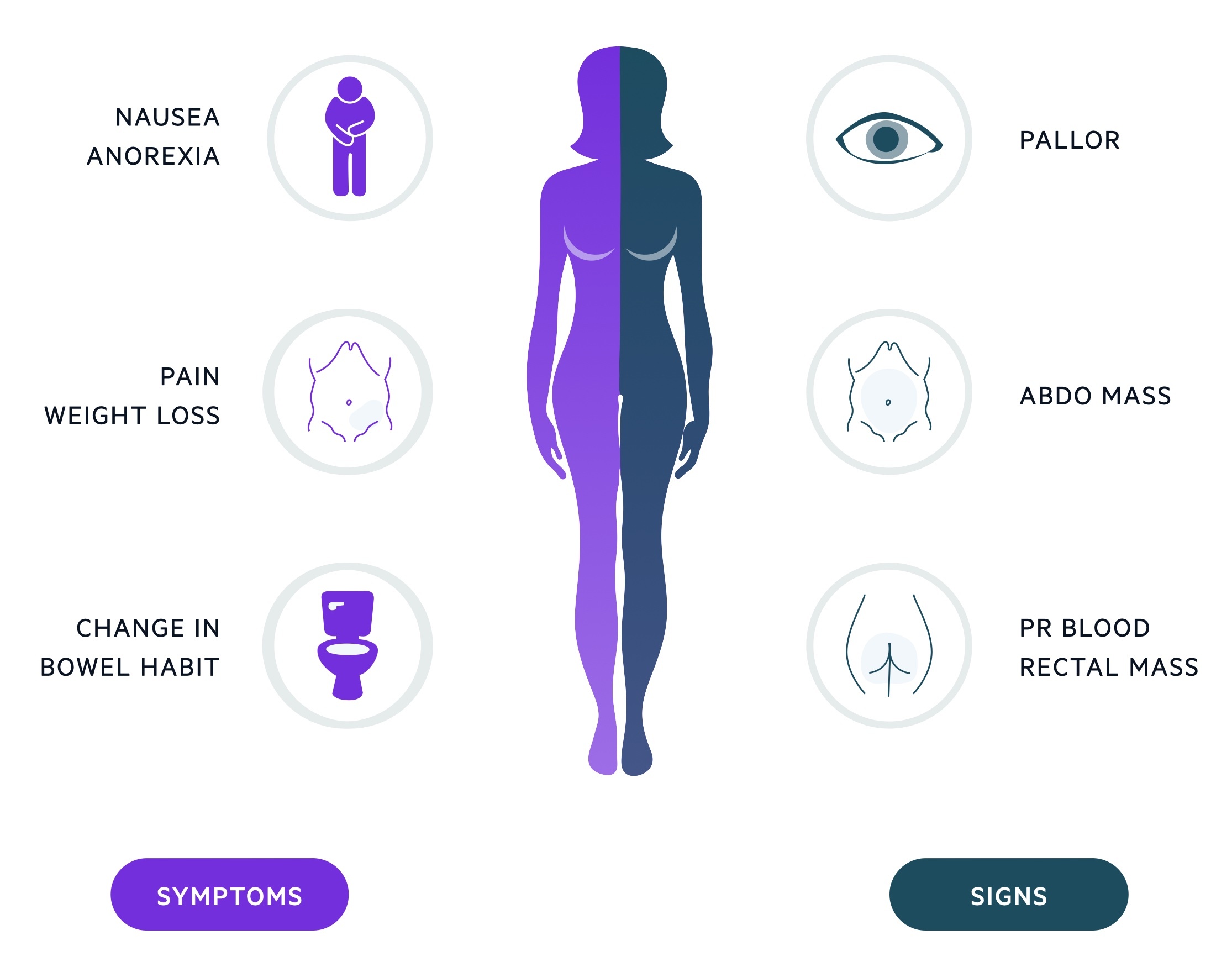

Colorectal cancer may present with change in bowel habit, anaemia and weight loss.

It is often asymptomatic and diagnosed through screening or incidentally during investigations ordered for other reasons. Diagnosis also frequently follows the recognition of an unexplained (and typically iron deficient) anaemia – a key indication for endoscopy.

Features are often non-specific, commonly change in bowel habit (either to constipation or diarrhoea) and weight loss are reported.

Up to 1/3 of cases present with bowel obstruction. See our notes on bowel obstruction for more on this presentation.

Symptoms

- Change in bowel habit

- Weight loss

- Malaise

- Tenesmus

- PR bleeding

- Abdominal pain

Signs

- Pallor

- Abnormal PR exam

- Abdominal mass

Metastatic disease

- Hepatomegaly

- Jaundice

- Abdominal pain

- Lymphadenopathy

A whole myriad of features may develop depending on the location of metastasis. Haematogenous spread leads to liver mets as a result of the portal system, though rectal disease may drain via the inferior rectal vein to the IVC and result in lung deposits. The bone and brain are also commonly affected.

Right vs Left

Though lesions throughout the bowel follow the same pathogenesis, the pattern of growth shows some variability.

Lesions arising on the right side of the colon have a tendency to develop as masses arising from a dysplastic polyp. The classical presentation is that of iron-deficiency anaemia.

Lesions arising from the left side of the colon have a tendency to grow circumferentially often creating an ‘apple core’ appearance. This may lead to narrowing of the lumen and symptoms of change in bowel habit and eventual obstruction.

Screening

The NHS runs a national screening programme for CRC.

The NHS uses the Faecal Immunochemical Test (FIT) to screen for colorectal cancer. This tests for the presence of blood in the stool. People aged 60-74 (and expanding to 56 years-old from 2021) will be invited to complete a home test kit consisting of a FIT every two years. After the age of 75, people can request further tests every two years. Approximately 98% have a normal result. Those with abnormal results will be invited for colonoscopy.

A bowel scope screening (one-off flexible sigmoidoscopy) programme for people aged 55 has been suspended since the COVID-19 pandemic and difficulties with rolling out services across the country.

Additional screening programmes exist for those with familial history or genetic predispositions that are not covered here.

Referral

Patients with features suggestive of colorectal cancer should be referred for further review or investigation on an two-week wait basis.

The majority of cases can be sent ‘straight to test’ for a colonoscopy after review of the GP referral by a specialist nurse. Patients in whom colonoscopy may be complicated or who have a contraindication should be reviewed in colorectal clinic first. This may include patients with dementia, learning difficulties, physical impairments, on anticoagulation or with anal pathology.

NICE guidance NG 12: Suspected cancer: recognition and referral, advise patients should be referred on a target (two-week wait) pathway if:

- Aged 40 and over with unexplained weight loss and abdominal pain or

- Aged 50 and over with unexplained rectal bleeding or

- Aged 60 and over with:

- Iron-deficiency anaemia or

- Changes in their bowel habit or

- Tests show occult blood in their faeces or

- Consider in patients with a rectal or abdominal mass

It also advises to consider a target referral for colorectal cancer in adults younger than 50 with rectal bleeding and any of the following:

- Abdominal pain or

- Change in bowel habit or

- Weight loss or

- Iron-deficiency anaemia

The NICE guidelines are several years old. Many regions publish additional local guidelines that GPs may follow, some of which have additional criteria. Local guidance should always be checked. Scotland has its own referral guidelines.

NICE guidance NG 12: Suspected cancer: recognition and referral (Jan 2021 update) also advises on the use of FIT (Faecal Immunochemical Test). It helps assess the risk of CRC in those without rectal bleeding who meet the following criteria:

- Are aged 50 and over with unexplained

- Abdominal pain or

- Weight loss

- Are aged under 60 with:

- Changes in their bowel habit, or

- Iron-deficiency anaemia

- Adults without rectal bleeding who are aged 60 and over and have anaemia even in the absence of iron deficiency.

In the future, we may use FIT more frequently as the first test in certain patient groups prior to more invasive investigations. Outside of the guidance, if clinicians have concerns (e.g. family history) they should use their judgement and refer the patient where necessary.

Diagnosis

Colonoscopy is the gold-standard investigation for those with suspected CRC.

Endoscopy

Colonoscopy is the gold-standard investigation. It allows visualisation of the colon, identification of malignant lesions and pre-malignant or suspicious polyps.

Colonoscopy can be technically challenging in some individuals and a completion colonoscopy (reaching and visualising the terminal ileum) is not always possible. The procedure is typically done with conscious sedation and some patients cannot tolerate this. Here, options include colonoscopy under a general anaesthetic or a CT pneumocolon.

It is not without complication, in particular perforation of the colon – something patients with diverticular disease are at increased risk off. The patient must also be able to comply with the bowel preparation – where a specific diet is followed and agents like Moviprep are given. For some, in particular elderly patients, this may best be done as an inpatient.

Flexible sigmoidoscopy may also be used in individuals not able to undergo colonoscopy, with left sided lesions incidentally seen on axial imaging or as part of screening. It tends to allow visualisation up to the splenic flexure.

CT pneumocolon & CT abdomen/pelvis

In those not suitable for, or declining endoscopy a CT pneumocolon may be used to identify lesions. This has the clear disadvantage of not allowing removal of polyps or biopsy of lesions. In addition some lesions may be missed.

Studies comparing it as a first line investigation to colonoscopy are ongoing. It is feasible in the future it will be used as a screen prior to endoscopy.

It is not non-invasive – air insufflation via the rectum is needed to attain the images. In addition bowel preparation is needed although there is normally a less intensive preparation option.

In those unable to tolerate a CT pneumocolon, a plain CT abdomen/pelvis (with or without contrast) can be arranged.

Further investigations

Further investigations allow assessment of distant spread and key-organ function to help guide management.

Bloods

- FBC

- Serum iron, transferrin saturation, TIBC

- Renal function

- LFT

- Clotting screen

Tumour markers

Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA): A serum marker indicative of colorectal cancer. It is not used to screen for colorectal cancer but may be measured at time of diagnosis and used to monitor as a marker of recurrence.

Imaging

CT chest abdomen/pelvis: The majority of patients will undergo CT scanning pre-operatively to characterise disease burden and sites of possible metastatic spread.

MRI liver: Offers better identification and characterisation of suspected liver metastasis.

MRI rectum: May be used to better stage rectal tumours.

Endoanal USS: May be used to better stage rectal tumours.

PET/CT: Does not tend to be routine but may be used to help with staging, prior to pelvic exenteration or in the setting of recurrence.

Staging

Colorectal cancer is staged using the TNM classification.

Tumour

- TX: Primary tumour cannot be assessed.

- T0: No evidence of primary tumor

- Tis: Carcinoma in situ, intramucosal carcinoma (involvement of lamina propria with no extension through muscularis mucosae)

- T1: Tumor invades submucosa (through the muscularis mucosa but not into the muscularis propria)

- T2: Tumor invades muscularis propria

- T3: Tumor invades through the muscularis propria into the pericolorectal tissues

- T4:

- T4a: Tumor invades through the visceral peritoneum (including gross perforation of the bowel through tumor and continuous invasion of tumor through areas of inflammation to the surface of the visceral peritoneum)

- T4b: Tumor directly invades or adheres to other adjacent organs or structures

Node

- NX: Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed

- N0: No regional lymph node metastasis

- N1: Metastasis in 1 – 3 regional lymph nodes

- N1a: Metastasis in 1 regional lymph node

- N1b: Metastasis in 2 – 3 regional lymph nodes

- N1c: No regional lymph nodes are positive but there are tumor deposits in the subserosa, mesentery or nonperitonealized pericolic or perirectal / mesorectal tissues

- N2: Metastasis in 4 or more regional lymph nodes

- N2a: Metastasis in 4 – 6 regional lymph nodes

- N2b: Metastasis in 7 or more regional lymph nodes

Metastasis

- M0: No distant metastasis by imaging; no evidence of tumor in other sites or organs (this category is NOT assigned by pathologists)

- M1: Nistant metastasis

- M1a: Metastasis confined to 1 organ or site without peritoneal metastasis

- M1b: Metastasis to 2 or more sites or organs is identified without peritoneal metastasis

- M1c: Metastasis to the peritoneal surface is identified alone or with other site or organ metastases

NOTE: Non-regional lymph node spread is considered M1a disease.

Management

Management of colorectal cancer may involve surgery, endoscopic techniques, radiotherapy, systemic anti-cancer therapy and palliative care.

The management of colorectal cancer is complex and dependent on a myriad of factors. This includes the patients wishes, stage and grade, co-morbidities and services available. Patients should be counselled on the condition and its management options.

Surgery

In appropriate patients, surgery is the mainstay of treatment. Traditionally procedures were open, however there is now a drive toward laparoscopic surgery which appears to be associated with reduced short term complications and length of stay.

Stoma

Many patients will require a stoma following their operation. This is normally formed to protect the anastomosis between the proximal and distal segments of remaining bowel – this is particularly true of operations with low anastomosis (e.g. low anterior resection) when anastomotic leak is more common.

The stoma will typically be temporary with a plan to reverse it during a second procedure, normally several months after their primary operation. The surgeon and specialist nurse should discuss the potential need and complications of a stoma. The stoma site should be marked pre-operatively.

Nutrition

Patients nutritional status should be assessed pre and post-operatively. Prepared pre-operative carbohydrate drinks are now commonly given and are thought to aid recovery.

Rectal cancer

NICE recommends offering one of the following procedures to patients with early rectal cancer (cT1-T2, cN0, M0):

- Transanal excision

- Endoscopic submucosal dissection

- Total mesorectal excision

Surgical management with total mesorectal excision in conjunction with anterior resection or AP resection is often used in more advanced rectal cancers. Patients with cT1-T2, cN1-N2, M0, or cT3-T4, any cN, M0 should be offered pre-operative (neoadjuvant) radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy

Those with locally advanced or recurrent rectal cancer should be managed at a specialist centre as the may need multi-visceral or beyond-TME surgery.

Colonic cancer

NICE recommend systemic pre-operative (neoadjuvant) chemotherapy is considered prior to surgery in those with cT4 disease. There is evidence this improves rate of clear surgical margins and survival.

There are many operations that can be carried out depending on the location of the tumour or an associated hereditary syndrome:

- Sigmoid colectomy

- Right hemicolectomy

- Left hemicolectomy

- Subtotal colectomy

- Total abdominal colectomy

Complications

Operations to resect colorectal tumours are major procedures and as such are associated with a number of complications. As with many operations there is a risk of infection (intra-abdominal, wound, urinary, chest), bleeding/haematoma and blood clots (DVT/PE) amongst others. During the procedure itself damage may occur to other structures – the ureters are of particular concern.

Anastomotic leak is a significant and feared complication. It most commonly affects operations with a low rectal anastomosis – as such these are often protected with a loop ileostomy. In the medium to long term patients may experience troubling change in their bowel habit. Sexual dysfunction is also relatively common.

There is a risk of death and an estimate may be obtained using the SORT score.

Neoadjuvant therapy

In patients undergoing surgical management, neoadjuvant therapy refers to those that are given prior to a patients operation. The decision to offer neoadjuvant therapies is guided by a specialist MDT with input from oncologists, radiologists, surgeons and specialist nurses.

Two examples where nice advise considering neoadjuvant treatments are:

- Rectal cancer cT1-T2, cN1-N2, M0, or cT3-T4, any cN, M0 should be offered neoadjuvant radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy.

- Colonic cancer with cT4 disease. Consider the use of chemotherapy. There is evidence this improves rate of clear surgical margins and survival.

Adjuvant therapy

In patients undergoing surgical management, adjuvant therapy refers to those that are given after a patients operation.

Again adjuvant therapy is guided by specialist MDTs. Some of the chemotherapy options used are:

- FOLFOX (FOLinic acid, Fluorouracil and OXaliplatin)

- CAPOX (CAPecitabine and OXaliplatin)

Metastatic disease

Patients with metastatic disease may be appropriate for metastasectomy or other local therapies to target metastatic deposits as well as systemic anti-cancer therapy.

Even in patients with incurable disease there may be merit in removing primary tumours. This can reduce the risk of local complications (e.g. fistula, obstruction) and may offer a survival advantage.

As always, management should be discussed and guided by an appropriate specialist MDT.

Liver metastasis

Patients with liver metastasis may be appropriate for aggressive treatment. Depending on the size, location and number of lesions they may be resectable:

- Simultaneously: Removed at the same time as the primary tumour

- Sequentially: Removed in a separate procedure either before or after the primary tumour.

For those that are not resectable, local ablative techniques and chemotherapy may be considered.

Lung metastasis

A number of techniques may be offer to treat disease affecting the lungs. NICE recommend considering metastasectomy, ablation and stereotactic body radiation therapy.

Peritoneal metastasis

NICE recommend offering systemic anti-cancer therapy to those with peritoneal disease. In addition at specialist centres cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) may be considered.

Prevention

Prevention is better than cure!

Modifiable risk factors

Patients should be encouraged to maintain a healthy balanced diet. The general advice of 5 fruits and vegetables a day applies to almost all.

It is unclear exactly what dietary components may increase the risk of CRC. There appears to be a link processed meats, in particular red meats. This is an area of ongoing research.

Smoking cessation services and help maintaining a health weight should be provided where necessary.

Medication

There is some evidence that aspirin may reduce the risk of CRC in patients with Lynch syndrome. Specifically daily aspirin taken for more than two years.

Prognosis

CRC is responsible for over 16,000 deaths each year in the UK.

Following diagnosis with CRC:

- 78% survive one year

- 58% survive five years or more

Prognosis is related to both stage and age at diagnosis. Around 70% of those 15-39 survive 5 years compared to around 40% of those aged over 80. Interestingly survival is also higher in those aged 60-69 – this may be related to the screening programme.

One year survival is around 98% if diagnosed at stage 1, compared to 44% in those with stage 4 disease.