Definition & classification

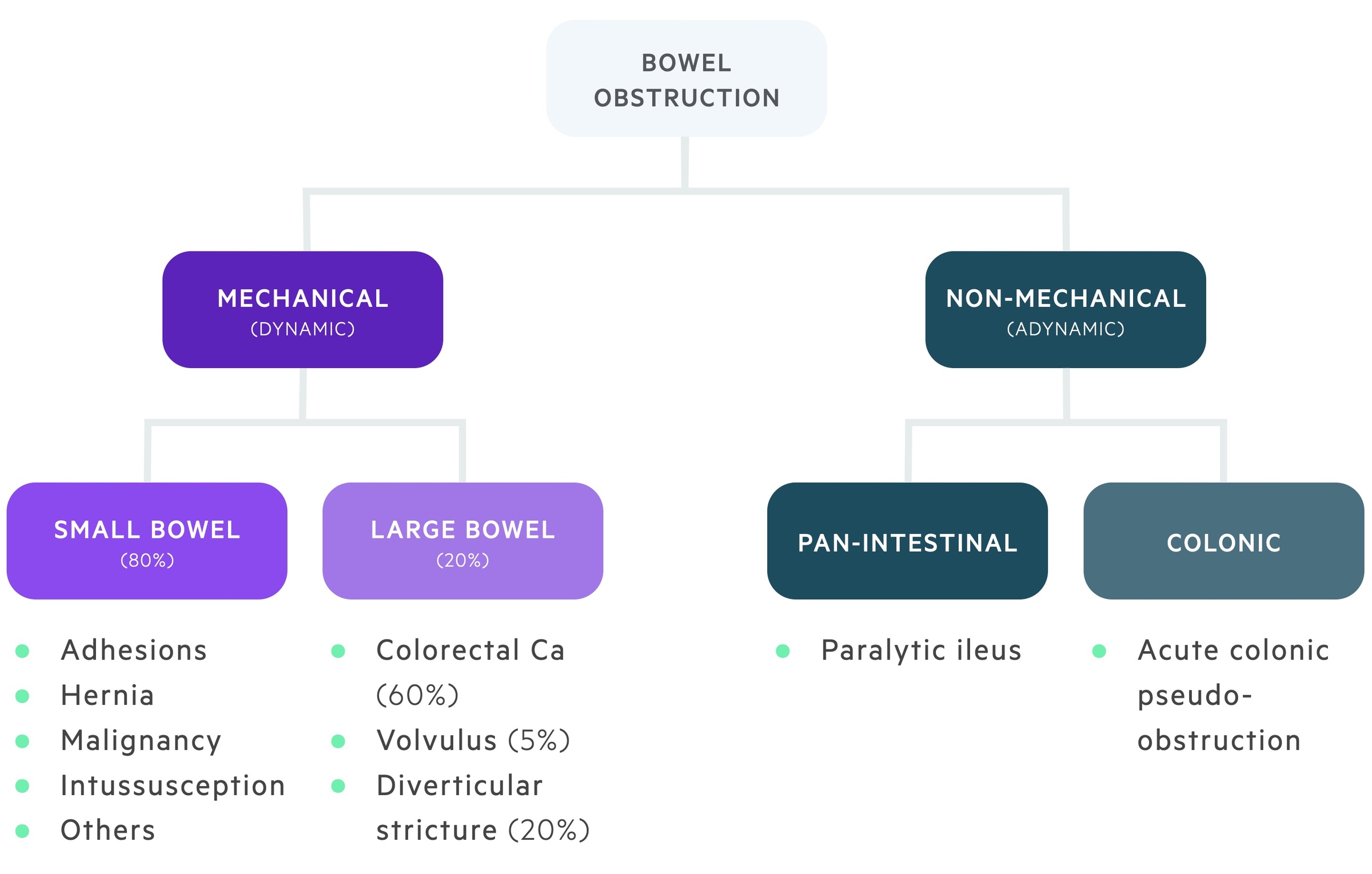

Bowel obstruction refers to complete or partial disruption of the normal flow of gastrointestinal content.

It may occur in the small or large intestines, and is secondary to mechanical obstruction and/or peristaltic failure (non-mechanical).

Classifying bowel obstruction depends on the location, segments of intestines involved, underlying aetiology and whether blood flow is compromised, which could lead to ischaemia and perforation.

- Complete obstruction: no fluid or gas is able to pass beyond the site of obstruction.

- Partial/incomplete obstruction: some fluid or gas is able to pass beyond the site of obstruction.

- Mechanical obstruction: physical blockage to the flow of gastrointestinal content.

- Non-mechanical obstruction (ileus): obstruction to flow secondary to neuromuscular dysfunction (e.g. failure in peristaltic activity).

- Closed loop obstruction: the bowel is obstructed at two points, this prevents proximal or distal decompression of contents. High-risk of rapid necrosis and perforation.

Mechanical

Mechanical (or dynamic) bowel obstruction refers to physical obstruction to normal flow of bowel contents.

Small bowel

The most common cause of mechanical small bowel obstruction within the western world is post-operative adhesions. These refer to strands of fibrous tissue that form following surgery and can lead to the abnormal adhesion between intra-abdominal tissue.

Another major cause of mechanical small bowel obstruction are hernias (e.g. inguinal hernias). Loops of bowel can become trapped within the hernial sac leading to obstruction and potentially strangulation and infarction if not managed urgently.

Other causes of small bowel obstruction are listed below:

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Malignancy

- Radiation enteritis

- Intussusception

- Gallstone ileus

- Other

Large bowel

It is estimated that 60% of patients with mechanical large bowel obstruction occurs secondary to colorectal malignancy.

Other causes of mechanical large bowel obstruction are listed below:

- Diverticular stricture (approx. 20% of mechanical large bowel obstruction)

- Volvulus (approx. 5% of mechanical large bowel obstruction)

- Hernia

Non-mechanical

Non-mechanical (or adynamic) bowel obstruction refers to a dilatation of the bowel in the abscence of mechanical blockage through failure of normal peristalsis.

Non-mechanical bowel obstruction is caused by impairment of the muscles or nerves responsible for peristalsis. It may be divided into a number of clinically distinct conditions.

Terminology varies widely here and some texts would only consider paralytic ileus here. We will also discuss acute colonic pseudo-obstruction and toxic megacolon.

Paralytic ileus

Paralytic ileus is the general slow-down of the intestines and affects the entire intestinal tract (small and large bowel).

Its aetiology is poorly understood though it is commonly seen post-operatively. Other triggers include abnormal electrolytes and systemic upset.

Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction

Also termed Ogilvie syndrome, ACPO refers to the dilations of the colon in the absence of mechanical obstruction. Its aetiology is poorly understood and likely multifactorial. A combination of systemic illness, medications and biochemical abnormalities are implicated.

The condition is also often seen in the post-partum setting, particularly following caesarian section.

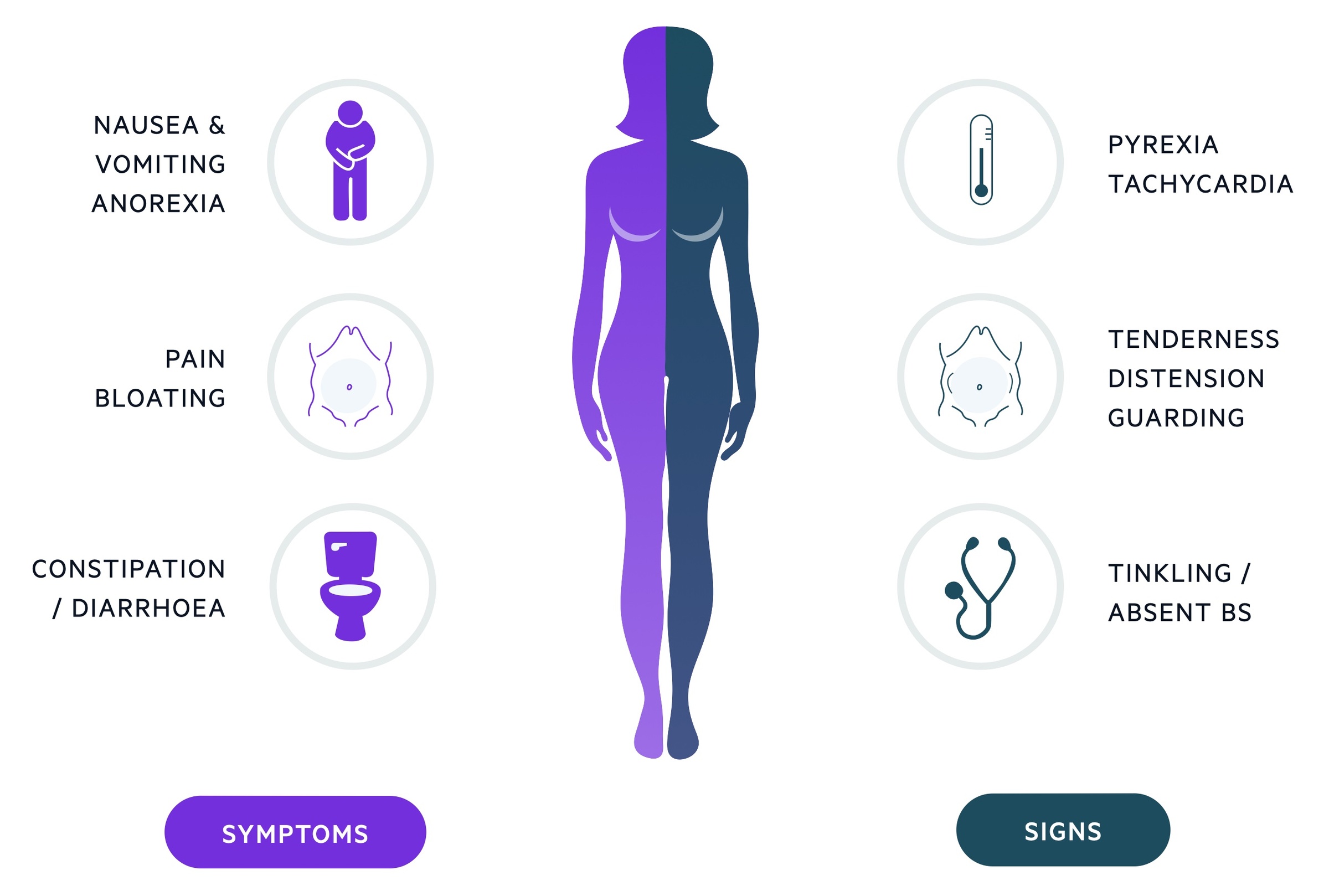

Clinical features

The classical features of bowel obstruction include abdominal pain, distension, vomiting & obstipation.

It is important to remember that each patient presents uniquely and no one feature is diagnostic. If the overall picture fits with a diagnosis of bowel obstruction arrange surgical review and consider imaging options.

Symptoms

- Abdominal pain

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Anorexia

- Small volume diarrhoea

- Obstipation

Signs

- Abdominal tenderness / peritonism

- Rebound

- Abdominal distention

- Abdominal mass (e.g. hernia)

- Dehydration

Signs of systemic upset may be present if significant dehydration or a complication (e.g. perforation, ischaemia) has occured.

Investigations

Biochemical abnormalities frequently seen in bowel obstruction include a raised lactate and inflammatory markers.

As bowel obstruction typically presents with acute abdominal pain it is important to investigate other potential causes. Furthermore, bowel obstruction can cause significant dehydration, electrolyte derangements and complications such as perforation. Therefore, investigations are essential to help exclude and treat these potential issues.

Bedside

- Observations

- ECG

- Fluid balance

- PR examination

- Pregnancy test

Bloods

- VBG/ABG

- FBC

- UE

- Magnesium

- Bone profile

- LFTs

- Amylase

- CRP

- Group and saves

Imaging

- Erect chest radiograph (check for free air)

- Abdominal radiograph

- CT abdomen/pelvis

Large amounts of subdiaphragmatic gas on CXR

Image courtesy of Dr Henry Knipe and Radiopaedia

NOTE: Lactate is a key biochemical marker in bowel obstruction, acting as an indicator for ischaemia. DO NOT however be deceived by a normal lactate which can be found despite significant ischaemia having occurred. As always it must be interpreted in the wider clinical context.

Imaging

In todays NHS, CT is (normally) a readily available investigation that can be arranged and completed in a relatively short period of time.

Plain film radiograph

At a basic level, being able to differentiate between dilatation of the small or large bowel is essential for all medical practitioners.

- Small bowel: Identification of the small bowel is based on the presence of the valvulae conniventes. These are circular folds, which help increase the surface area of the small intestines. On radiograph, these are seen as white lines which cross the lumen of the small bowel.

- Large bowel: Identification of the large bowel is based on the presence of haustra. These give the large intestines its sacculated appearance. On radiograph, these are seen as white lines, which do not cross the lumen of the large bowel.

- 3, 6, 9 rule: As a general rule of thumb, dilatation of the small bowel > 3cm, the large bowel > 6cm or the caecum > 9 cm, is suggestive of abnormal dilatation.

- Sigmoid volvulus: typical ‘coffee bean’ sign is described. Arises from left lower quadrant, haustra cannot be identified. Multiple air-fluid levels may be seen. Classical appearances often not present and a simple x-ray may not be diagnostic.

- Caecal volvulus: arises from the right lower quadrant, haustral pattern tends to be maintained. One air-fluid level seen. Classical appearances often not present and a simple x-ray may not be diagnostic.

It is important to note that if bowel obstruction is still suspected in patients with an equivocal X-ray, they may require further imaging in the form of computed tomography (CT).

Computed tomography

CT imaging of the abdomen provides a more comprehensive assessment of the specific site, severity, underlying aetiology and complications in bowel obstruction.

The additional benefit of CT imaging is that it helps to differentiate from the many other causes of acute abdominal pain, which present through the emergency department.

The finer details of CT imaging in patients with bowel obstruction is beyond the scope of these notes.

NOTE: Patients undergoing emergency laparotomies based on CT findings should, where possible, have these reported by a consultant radiologist.

NELA

The National Emergency Laparotomy Audit records and reviews emergency laparotomies and identifies ways in which practice can improve.

All emergency laparotomies should be recorded with data submitted to NELA. Based on data gathered thus far they have outlined a number of surgical and anaesthetic standards that should be followed, for those that are interested .

The NELA risk calculator can be used to give an estimate of a patient’s 30-day mortality. This also helps guide decisions such as the level of post-operative and the need for consultant anaesthetic support (though increasingly evidence shows the presence of a consultant anaesthetist and post-operative ITU/HDU care improves outcomes in all patient groups). Most importantly it helps us to explain risks of the operation to the patient and their family.

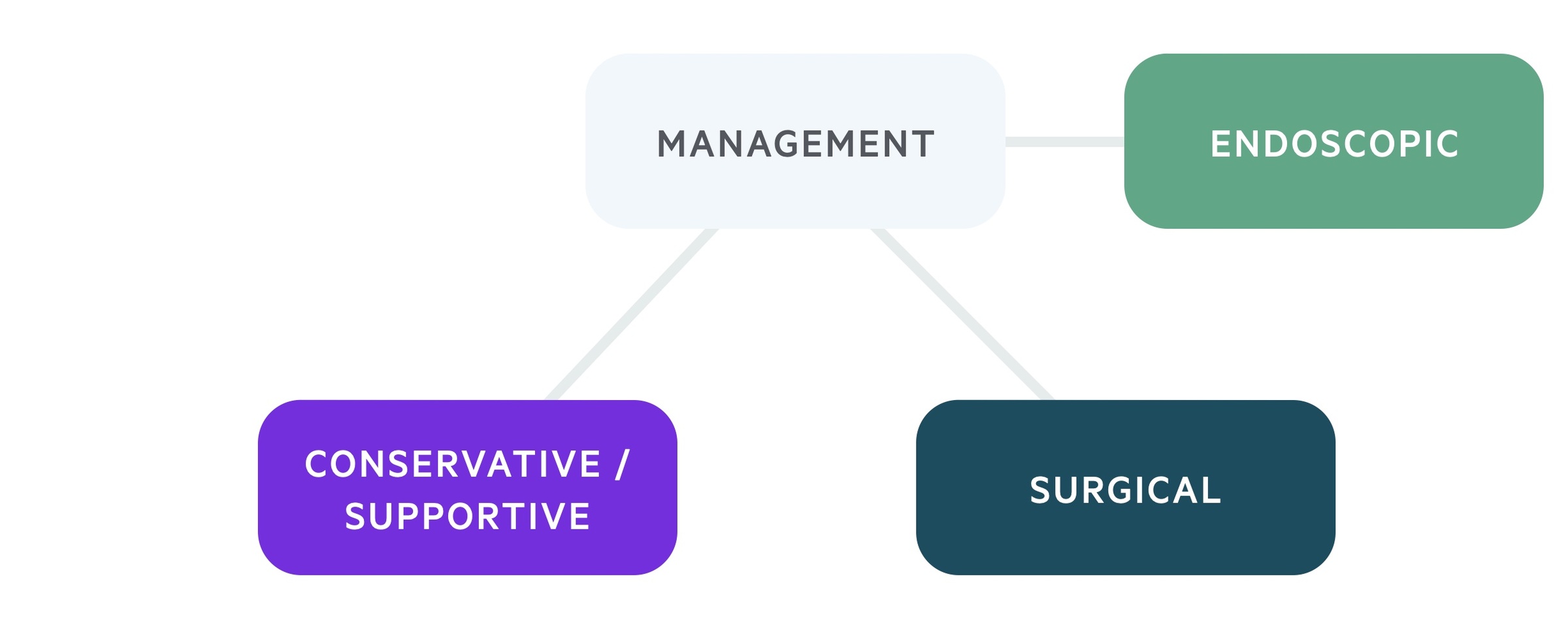

Management

The management of bowel obstruction largely depends on the underlying aetiology and whether there is any evidence of complications (e.g. ischaemia, perforation).

Surgical management is dependent on numerous factors including the underlying aetiology, patient factors and the presence of complications. It should be noted emergency surgery for bowel obstruction carries significant morbidity and mortality which must be conveyed to the patient and next of kin.

Supportive

Supportive therapy should be employed in all patients presenting with bowel obstruction, which involves bowel decompression and fluid resuscitation.

‘Drip and suck’: this commonly used phrase refers to the administration of IV fluid (drip) and the placement of an NG tube (suck). The use of a nasogastric tube (with regular aspirations) helps decompress the stomach and prevent aspiration. Fluid resuscitation is essential due to the inability to maintain oral hydration and the large amount of third spacing that occurs in bowel obstruction.

Other essential aspects in the management of patients with bowel obstruction include:

- Analgesia

- Urethral catheter and fluid balance monitoring

- Anti-emetics

- Antibiotics as needed

- Cardiac monitoring (esp. in patients with multiple co-morbidities due to the fluctuations in intravascular status)

- Correction of electrolytes

Large bowel obstruction

- Malignant obstruction: Surgical options (almost always via laparotomy) include defunctioning stoma and resection with primary anastomosis. Non-surgical options include endoscopic stenting. In non-surgical candidates this may represent the ‘definitive’ therapy, otherwise elective intervention should be planned.

- Benign stricture: Typically require surgical intervention.

- Volvulus: A sigmoid volvulus may resolve with a promptly placed flatus tube. Following this the patient should be considered for a definitive surgical procedure particularly if recurrent. Caecal volvulus more commonly requires immediate surgical intervention. Immediate surgical intervention is also indicated if there is evidence of perforation or ischaemia.

Small bowel obstruction

- Obstructing lesions/complications: An obstructing lesion, evidence of ischaemia or perforation, or a closed-loop are all indications for surgical management. Options include resection and primary anastomosis or resection with a defunctioning stoma. Surgery may be laparoscopic or via a laparotomy.

- Uncomplicated adhesional obstruction: Most will trial conservative management, with early administration of an oral contrast agent (such as gastrografin). If the gastrografin passes to the colon, there is evidence of resolving obstruction, and the patient should be closely monitored. If there is deterioration or no resolution of the obstruction then surgical management with adhesiolysis (+/- bowel resection) is indicated.

Paralytic ileus

Reversible causes should be considered and treated. Any electrolyte abnormality should be corrected and adequate IVF administered. NG tube decompression is often indicated. Exacerbating agents such as opiate analgesia should be reviewed.

Commonly seen in the postoperative setting, it tends to settle with conservative management.

Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction

The treatment of ACPO involves the identification and treatment of any underlying cause.

Neostigmine, a cholinesterase inhibitor, may be given to encourage motility. Endoscopic colonic decompression can be used in those failing to respond.

Those at increasing risk of or who have developed complications (e.g. necrosis, perforation) will typically need surgical management if they are appropriate candidates.