Introduction

Appendicitis may be defined as inflammation of the appendix.

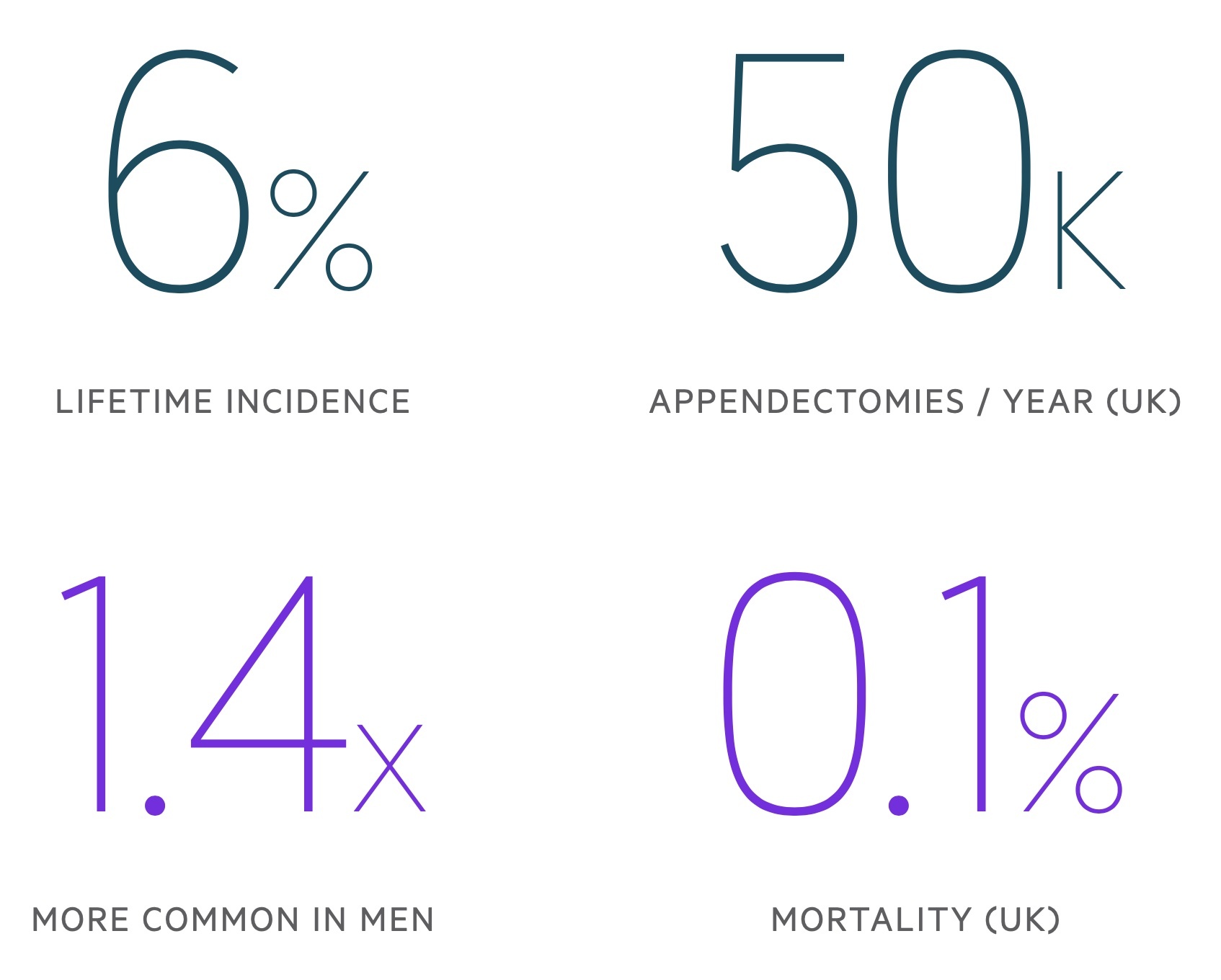

Acute appendicitis is a common surgical pathology that typically presents with acute abdominal pain. There are upwards of 50,000 cases in the UK each year.

Appendicitis has a slight male preponderance and is uncommon at the extremes of age. The majority of cases occur in those aged 15-59 years old.

Anatomy

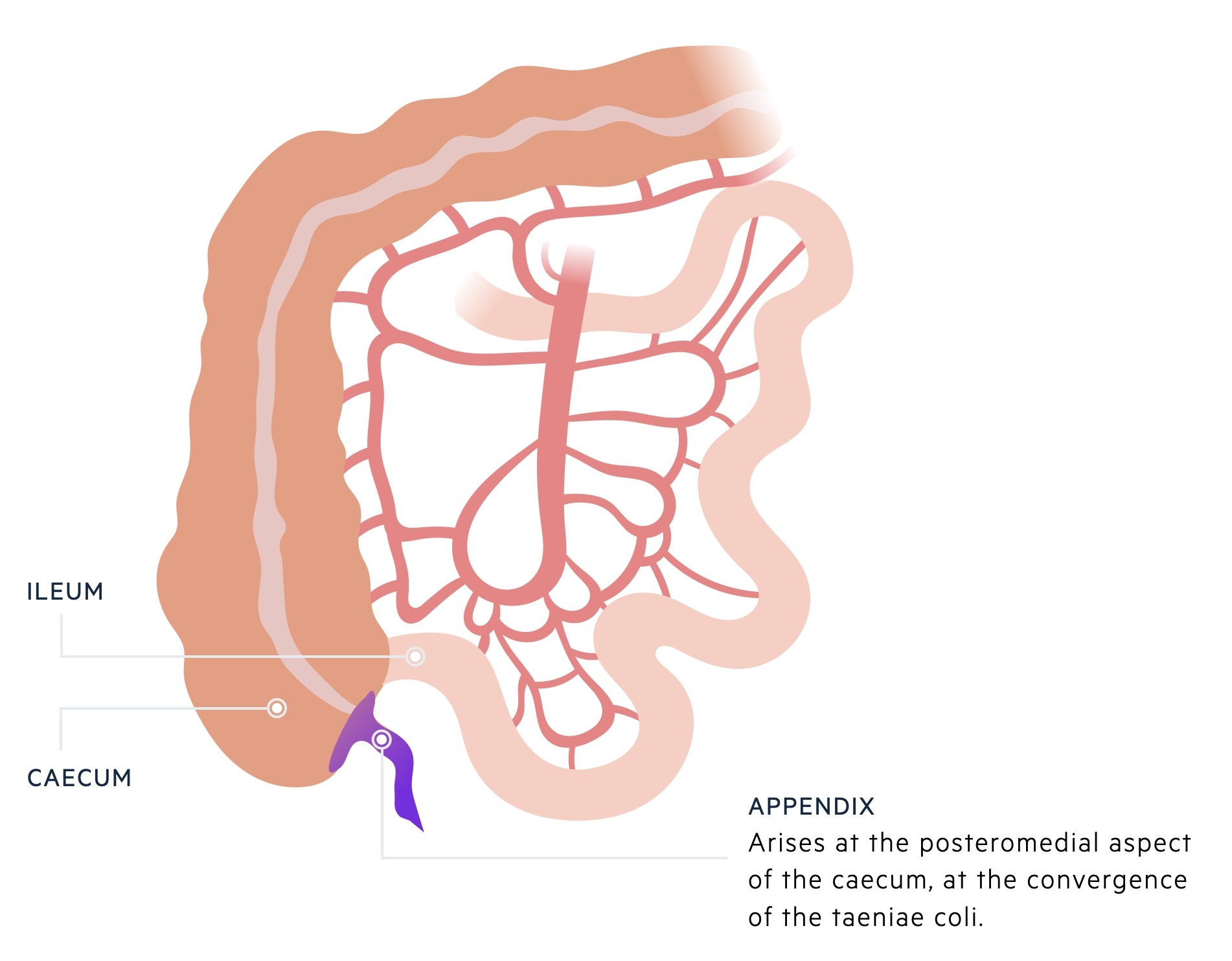

The appendix is a short appendage, normally 5-10 cm long, that opens onto the caecum.

The appendix may also be referred to as the vermiform (to resemble a worm) appendix. It is a blind-ended tube that arises at the posteromedial aspect of the caecum at the convergence of the taeniae coli.

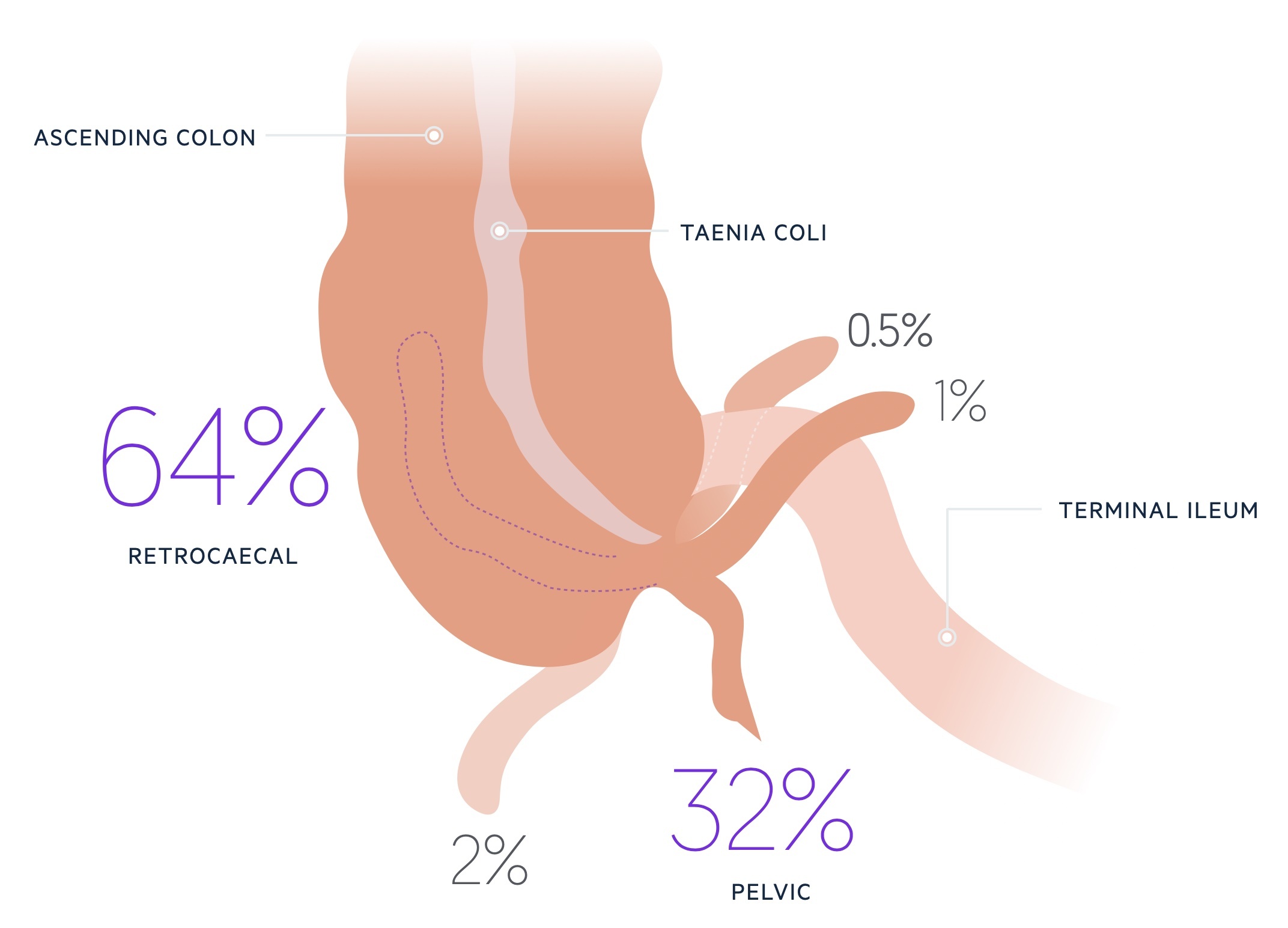

Whilst the base is consistent the appendix itself has a variable position. The majority are either retrocaecal (around 60%) or pelvic (around 20-30%) – it should be noted these figures vary substantially from study to study. The remaining are preileal, postileal, subcaecal or paracaecal.

The appendiceal mesentery hangs from the terminal ileum and contains the appendiceal branch of the ileocolic artery (from the superior mesenteric artery).

Aetiology & pathophysiology

Appendicitis is normally caused by obstruction of the lumen of the appendix.

Appendiceal obstruction may result from a variety of causes. One of the most common causes are faecoliths. These are hard collections of stool that form and block the appendiceal lumen. Other causes include lymphoid hyperplasia, fibrous stricture or carcinoid tumours.

Appendicitis is uncommon at the extremes of age. The young have a relatively wide appendiceal lumen, whilst in the elderly, it is almost entirely obliterated.

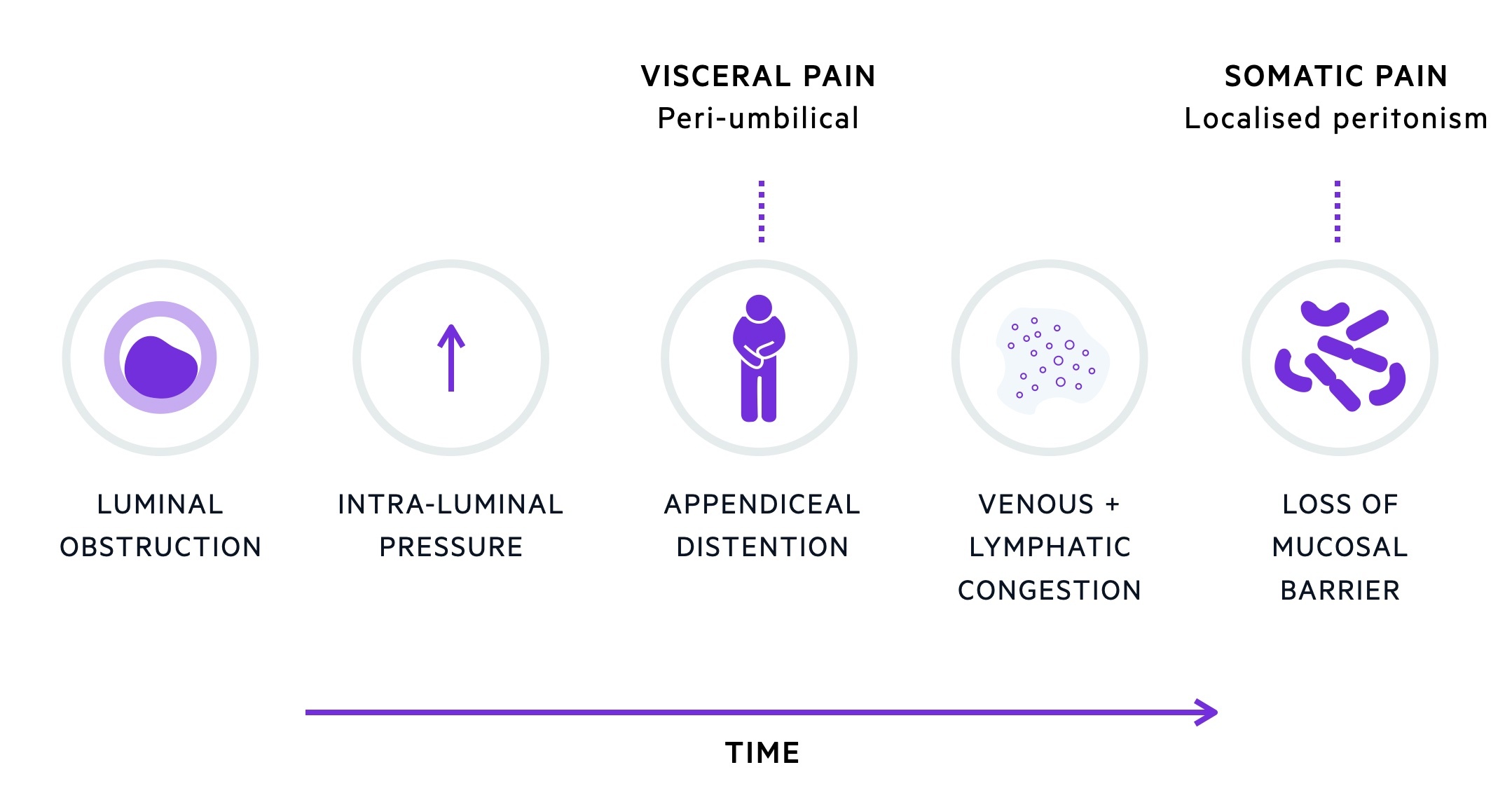

Obstruction of the appendiceal lumen causes stasis and resultant bacterial overgrowth. The proliferation of bacteria leads to an increase in intraluminal pressure. As the pressure rises in the appendix it causes venous and lymphatic congestion. As the pressure rises further, the arterial supply to the appendix becomes compromised leading to gangrene, perforation and generalised peritonitis.

The risk of perforation increases with time though varies between individuals. One study showed the risk of perforation to be 20% at 24 hours whilst another estimated it to be 15-35% at 72 hours.

Clinical features

Patients classically complain of a colicky, peri-umbilical pain which migrates to the right iliac fossa (RIF) and becomes constant.

Common clinical features associated with acute appendicitis include nausea, anorexia and constipation. Diarrhoea may be seen but is typically mild when present.

Acute appendicitis is uncommon at the extremes of age where it also tends to have an atypical presentation. Pregnant women may have a displaced appendix resulting in flank pain. A high degree of clinical suspicion is required as delayed treatment results in high morbidity and mortality in both the mother and foetus.

Symptoms

- Classical migratory abdominal pain

- RIF pain

- Nausea

- Anorexia

- Constipation

Signs

- RIF tenderness

- Percussion tenderness

- Localised guarding

- Tachycardia

- Pyrexia

Additional signs

Rovsing sign: pain in the RIF on palpation of the LIF.

Psoas sign: the patient lies on their left side with knees flexed, positive when there is pain in the RIF on passive extension of the right hip.

Obturator sign: pain in the RIF on passive internal rotation of a flexed right hip.

Investigations & diagnosis

Appendicitis is normally suspected based on the history and examination and may be confirmed with imaging.

Bedside

- Observations

- Urine dip

- Pregnancy test

Bloods

- FBC

- U&Es

- CRP

- LFTs

- Amylase

- Group & save

- Clotting screen

At least one of the inflammatory markers – either WCC or CRP – is normally elevated with the exception of those presenting early in the disease process.

Imaging

Ultrasound: may identify appendicitis, though sensitivity is operator-dependent. Pelvic ultrasound is often used in female patients where the differential includes gynaecological pathology.

Computed tomography: the use of CT to confirm the diagnosis of appendicitis is becoming increasingly commonplace particularly in older patients or if there is diagnostic uncertainty.

Alvarado score

The Alvarado score gives an estimate of the likelihood of appendicitis based upon two major and six minor criteria.

Management

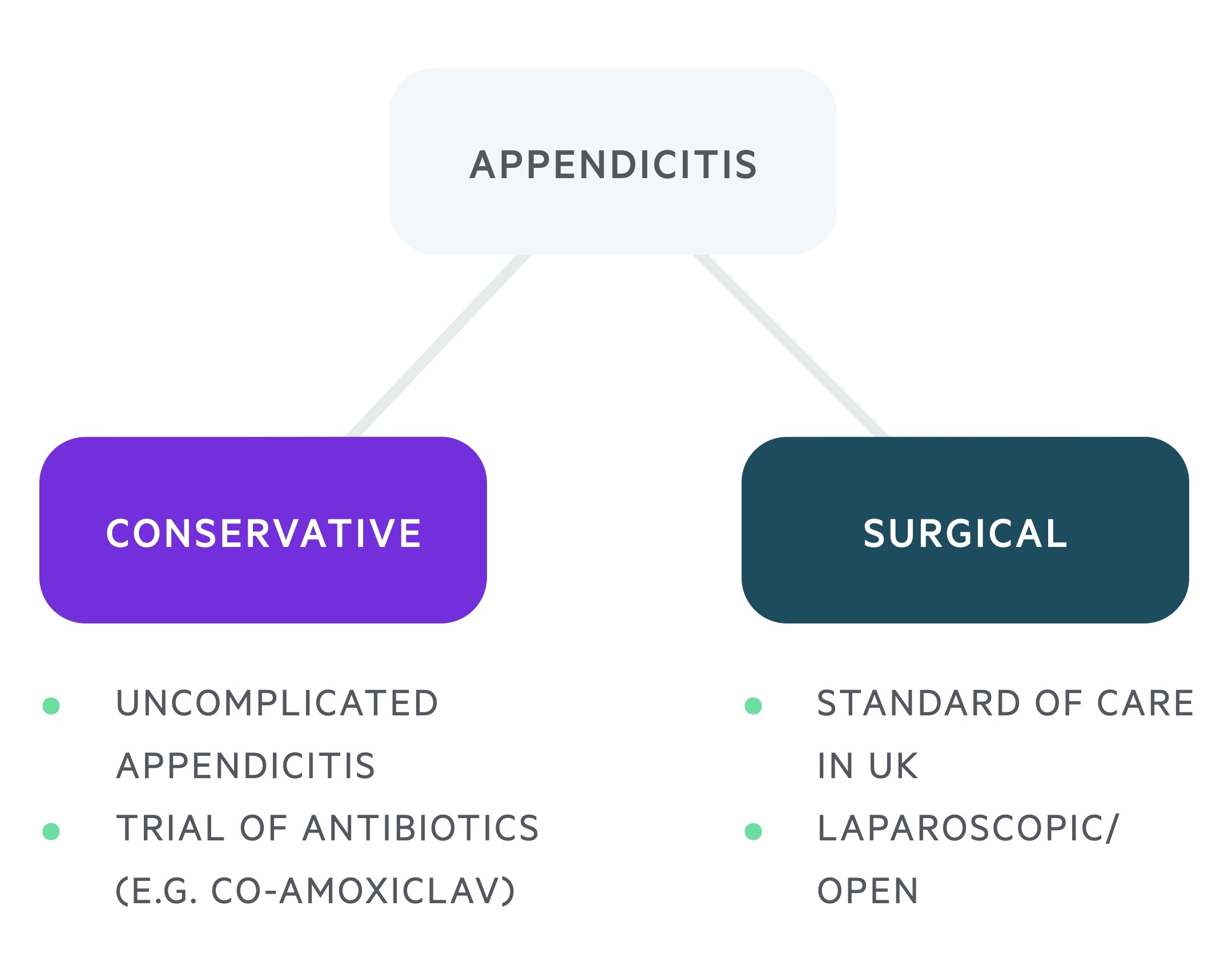

Appendicitis may be managed in a conservative or surgical manner.

Conservative

A number of studies (BMJ, JAMA) have shown that uncomplicated acute appendicitis may be treated initially with antibiotics (co-amoxiclav is commonly used in the absence of a penicillin allergy). A proportion of these patients, 27% in one study, required surgery within one year. Beyond this, there would likely continue to be a risk of re-developing appendicitis.

Surgical

In the UK, the majority of patients with suspected appendicitis receive surgical management in the form of a laparoscopic appendicectomy (with conversion to open surgery when necessary). This is a ‘keyhole’ procedure with high success and low complication rates.

Pre-operatively, antibiotic therapy should be commenced (co-amoxiclav is commonly used in the absence of a penicillin allergy) and normally continued for 7 days only if pus or perforation is noted intra-operatively. Depending on the operative findings a temporary drain may be inserted.

Surgical management in those with an appendiceal mass (a collection of pus and stuck bowel) would likely be complicated by inflammation and adhesions. As such simple localised cases may be treated with antibiotics alone. Larger abscesses may benefit from a percutaneous drain and complicated loculated disease may necessitate surgical intervention.