Overview

Acute cholecystitis refers to inflammation of the gallbladder most commonly occurring due to impacted gallstones.

After biliary colic, acute cholecystitis is the second most common complication of gallstones (cholelithiasis) affecting an estimated 0.3-0.4% of patients with asymptomatic gallstones each year. Relatively rarely acute cholecystitis occurs in the absence of gallstones (acalculous cholecystitis).

Management aims to treat the infection and symptoms (antibiotics, fluids, analgesia) and prevent recurrence (laparoscopic cholecystectomy – ‘hot’ or interval).

See our Cholelithiasis notes for more about the aetiology, types and risk factors.

Calculous cholecystitis

Cholelithiasis (gallstones) are by far the most common cause of acute cholecystitis.

Cholelithiasis

Gallstones affect up to 20% of the population. The prevalence of gallstones increases with advancing age before levelling off in the sixth – seventh decade of life. They are more common in women and tend to affect those of Caucasian, Native American and Hispanic backgrounds more.

Outside of haemolytic anaemias, gallstones are rarely seen in childhood. The vast majority of people with gallstones will remain asymptomatic (80%). There are a number of risk factors are associated with the development of cholelithiasis:

- Age

- Female sex

- Genetic predisposition

- Obesity

- Rapid weight loss / prolonged fasting

- Diabetes

- Medications (e.g. oestrogen replacement therapy, ceftriaxone, octreotide)

- Crohn’s disease

- Diet (high in triglycerides, refined carbohydrates)

- Haemolytic anaemia

Acute calculous cholecystitis

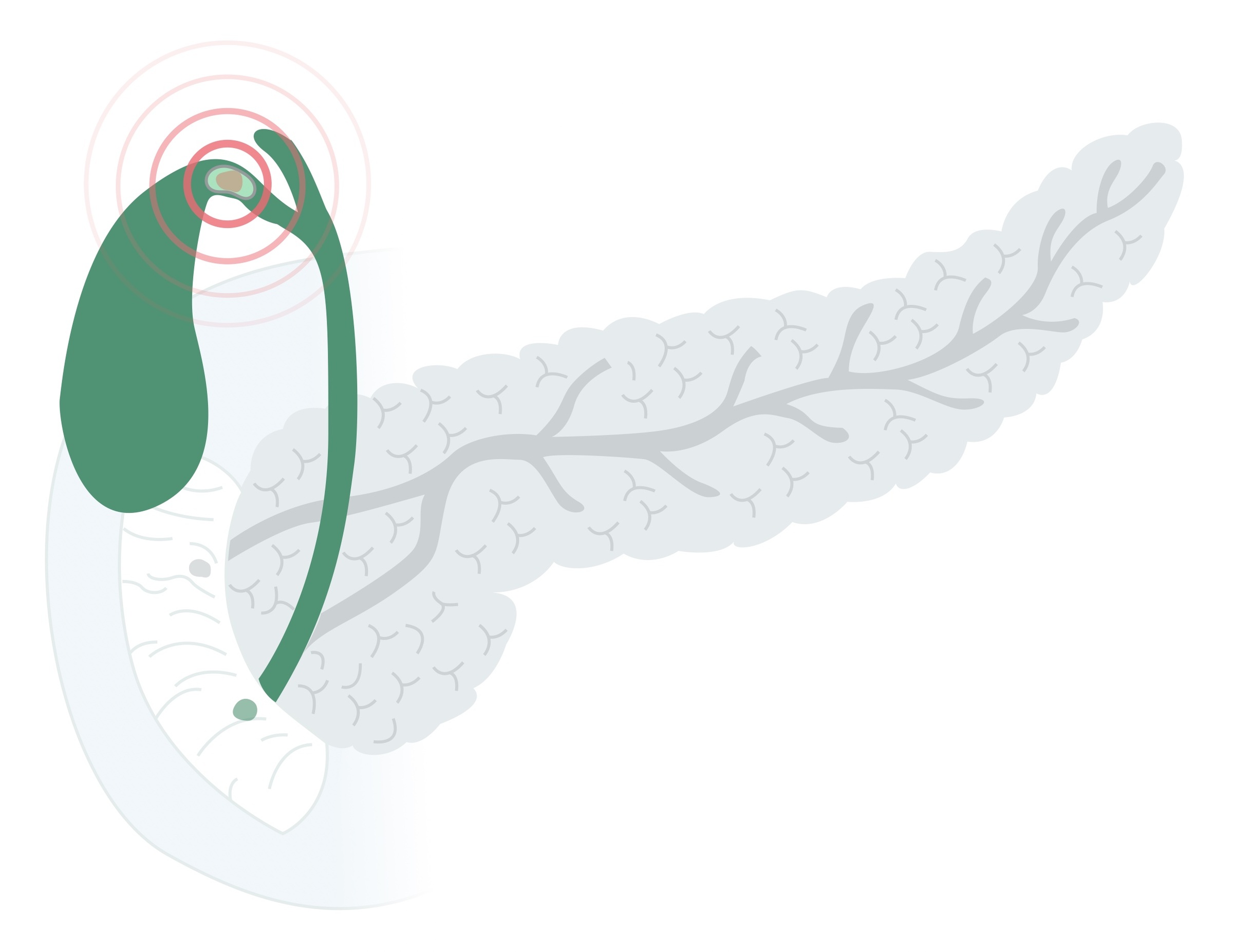

Inflammation and infection occur when a stone becomes impacted in the cystic duct (see Cholelithiasis notes to review the basic anatomy).

The exact pathogenesis is still not understood and it is thought the presence of additional mediators is required for cholecystitis to occur. An impacted stone leads to impaired drainage of gallbladder contents and the release of inflammatory mediators.

Though patients with acute cholecystitis are always treated with antibiotics some have posited that a significant proportion of patients have a sterile inflammation.

Acalculous cholecystitis

Acute acalculous cholecystitis refers to gallbladder inflammation in the absence of gallstones.

Acalculous cholecystitis is far less common than calculous cholecystitis and is normally seen in patients with significant systemic upset or following major surgery. Risk factors include:

- Diabetes

- Age

- Recent major surgery (e.g. cardiac surgery)

- Myocardial infarction

- Sepsis

- Major burn

- Major trauma

- Cancer

- Immunocompromised patients

- Vasculitis

- CKD

Again the pathogenesis is not fully understood but is thought to relate to biliary stasis and/or gallbladder ischaemia. In a proportion of cases, infection is the primary cause but it is thought infection is normally secondary to established inflammation.

Clinical features

Acute cholecystitis presents with abdominal pain, tenderness and signs of infection.

Symptoms

- RUQ / epigastric pain

- Nausea / vomiting

- Fevers

Signs

- RUQ / epigastric tenderness

- RUQ / epigastric guarding

- Pyrexia

- Tachycardia

- Hypotension (severe cases)

Murphy’s sign

Murphy’s sign is indicative of cholecystitis. As the patient breathes out, place your hand below the right costal margin. As the patient breathes in the inflamed gallbladder moves inferiorly to the hand causing the patient to catch their breath. To be considered positive, it should be absent on the left side.

Investigations

Acute cholecystitis is most commonly confirmed on USS or CT abdomen/pelvis.

Patients typically present with upper abdominal pain, tenderness and fever. Most patients are haemodynamically stable but the condition can present with significant sepsis. Blood tests reveal elevated inflammatory markers and mild derangement of the liver function tests is common.

Bedside

- Observations

- BM

- Urine dip

- Pregnancy test (any woman of child-bearing age)

Bloods

- Full blood count

- Urea & electrolytes

- CRP

- Liver function tests

- Amylase

Imaging

Ultrasound: in acute cholecystitis gallstones and a ‘radiological’ Murphy’s sign may be seen. Suggestive findings include a thickened gallbladder and pericholecystic fluid. It also allows for the assessment of the CBD.

Computed tomography: may be used to demonstrate cholecystitis and exclude alternative causes of symptoms. Again a thickened gallbladder and pericholecystic fluid may be seen. It has a poor sensitivity (around 60-70%) for picking up simple gallstones, only clearly demonstrating stones that are calcified.

MRCP: magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography offers excellent visualisation of the biliary tree. Arranged if there is suspicion of stones in the biliary tree.

Acute calculous cholecystitis on USS showing pericholecystic fluid and an oedematous wall

Image courtesy of Dr Maulik S Patel and Radiopaedia

Special

ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography involves the endoscopic intubation of the ampulla of Vater. It offers excellent views of the biliary tree whilst allowing therapeutic intervention such as drainage. ERCP is now generally a therapeutic rather than diagnostic intervention (due to the advent of MRCP), in this setting used when stones are retained in the CBD.

Management

Acute cholecystitis is managed with intravenous antibiotics, fluids and cholecystectomy.

Medical care

Initial management should follow an ABC approach in those who are acutely unwell. The sepsis 6 protocol should be implemented when indicated. Key components of management include:

- Antibiotics: IV Augmentin would be a standard initial agent. A stat dose of an aminoglycoside (e.g. Gentamicin) may also be given.

- Fluids: intravenous fluids should be commenced in most patients, both resuscitation and maintenance fluids are required. Where patients are able to maintain hydration with oral intake this should be encouraged.

- Analgesia: should be tailored to the patient’s needs, age and co-morbidities. An example regimen would include regular codeine and paracetamol with oramorph as required for breakthrough pain.

Gallbladder drainage

Some patients become very unwell with their cholecystitis, do not improve with medical management and may develop gallbladder empyemas. Often the patient is not suitable for a ‘hot’ laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

In these patients, a percutaneous cholecystostomy (drain into the gallbladder placed by interventional radiology) may be more appropriate. Once recovered, patients are often discharged with this drain in situ until definitive management can be arranged.

Cholecystectomy

In patients with simple cholecystitis, the definitive management is with laparoscopic cholecystectomy. There are two main options:

- ‘Hot’ laparoscopic cholecystectomy: surgery is arranged within 72 hours (or at some centres up to one week) of the onset of symptoms. After this, the operation becomes technically more difficult until the inflammation settles.

- Interval laparoscopic cholecystectomy: if the ‘hot’ operation is not available or appropriate interval surgery may be indicated after a period of recovery.

Prior to cholecystectomy, it is key that CBD stones are excluded. All patients will have had a USS and set of LFTs as a minimum. If there is suspicion of CBD stones (e.g. dilated CBD or CBD stone on USS, raised bilirubin on LFTs) then there are two main options:

- MRCP +/- ERCP: MRCP allows for confirmation of stones in the biliary tree (if confirmed on other imaging you may proceed straight to ERCP). When present, ERCP allows for therapeutic intervention with stone retrieval +/- sphincterotomy +/- stent placement prior to cholecystectomy.

- On-table cholangiogram: less commonly available and technically challenging. During the laparoscopic cholecystectomy, the bile duct is intubated to allow the injection of dye with fluoroscopy in theatre to diagnose stones in the biliary tree. Various techniques may then be used to retrieve/expel stones.

In patients with significant co-morbidities, a cholecystectomy may represent unacceptable risk and as such more conservative measures trialed.