Overview

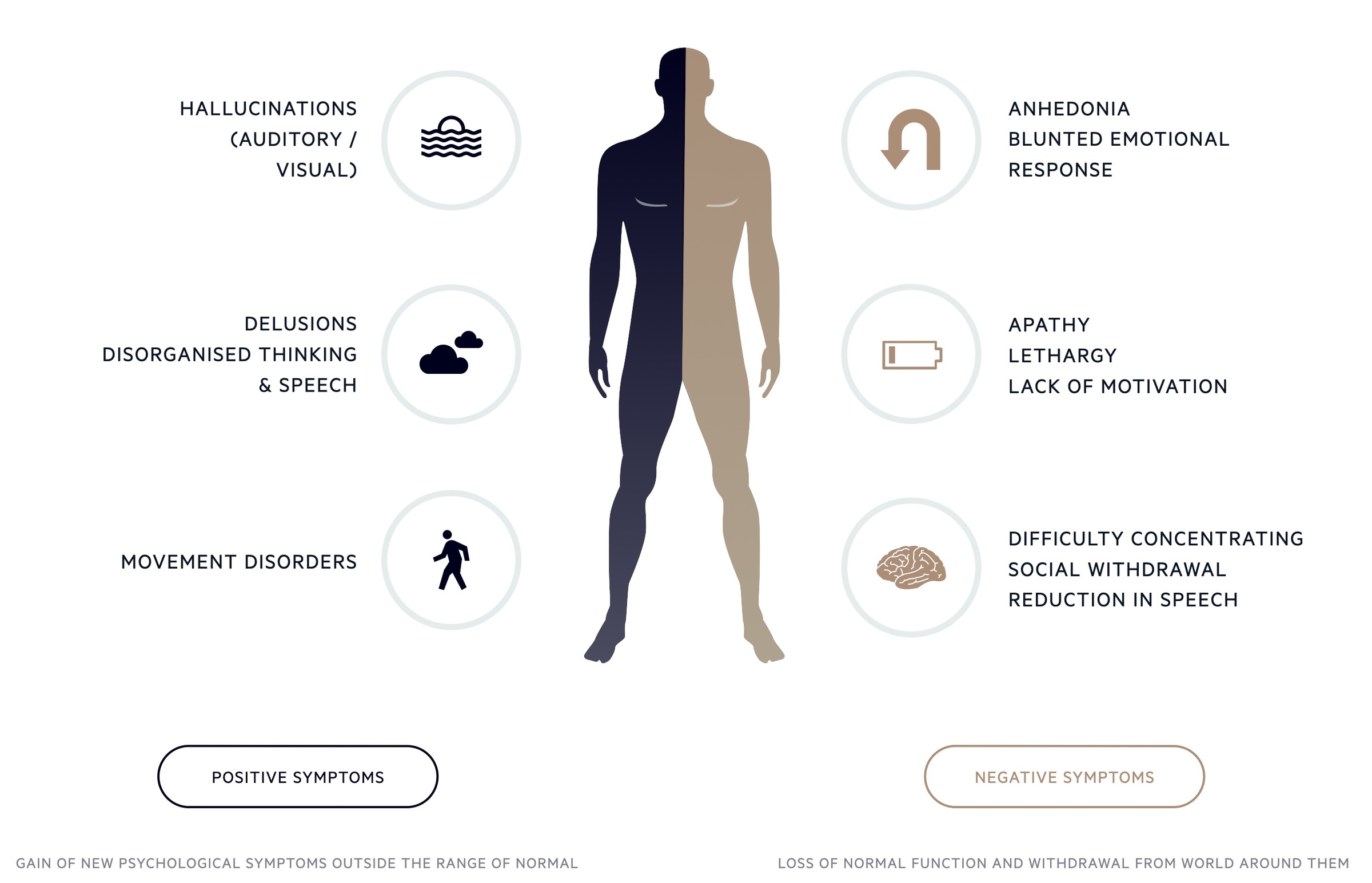

Schizophrenia, a form of psychosis, is characterised by distortion to thinking and perception and inappropriate or blunted affect.

Schizophrenia is the most common form of psychosis with an onset that is typically early in life (15 to 35). It is a chronic condition with a course characterised by episodes of acute psychosis.

Features that are common to psychoses are:

- Hallucinations: hallucinations can be defined as perceptions in the absence of stimuli. Most commonly auditory but may be visual or affect smell, taste, or tactile senses.

- Delusions: a fixed, false belief not in keeping with cultural and educational background.

- Thought and speech disorder: thought processes are altered and disordered. May manifest in a number of ways including word salad, neologism (creating new words), flight of thought, pressured speech, circumstantiality and Knight’s move thinking.

- Negative symptoms: these include alogia (poverty of speech), emotional blunting, social isolation, self-neglect and avolition (lack of self-will).

Management may include therapies (e.g. cognitive behavioural therapy) and medications (antipsychotics). There is an increased risk of suicide and cardiovascular disease in patients suffering from schizophrenia.

Epidemiology

In the UK, approximately 0.5%-1% will be diagnosed with a psychotic disorder during their lifetime.

Diagnosis is typically between the ages of 15 and 35. There have been some indications that those of south Asian or black heritage have an increased prevalence of schizophrenia. This is however disputed and may be related to cultural biases.

The prevalence is the same for men and women, though women tend to present when older (peak in the late twenties, compared to a peak in the early twenties in men).

Pathogenesis

The development of schizophrenia is complex, poorly understood and likely involves a myriad of factors and systems.

Studies using MRI scans of the brain have shown differences in the anatomy of some patients with schizophrenia compared to those without it. It appears these changes progress over time. Common findings include increased size of the ventricles and reduced whole-brain volume.

The function of antipsychotics as antidopaminergic is indicative of abnormalities in the action, production or breakdown of neurotransmitters. Increased activity of dopamine in the mesolimbic region is associated with symptoms of psychosis. It is likely numerous other neurotransmitters are involved in the pathogenesis.

Another area of research is the effect of abnormal immune function on the development of schizophrenia. Immune ‘triggers’ such as prenatal viral infections are being investigated as possible causes.

Risk factors

A number of risk factors have been associated with the development of schizophrenia.

It should be noted, it can be challenging to determine whether a factor is truly causative or just an association. Furthermore, it is difficult to say whether the association occurred prior to or because of the development of schizophrenia.

- Family history

- Pregnancy and birth complications (e.g. maternal malnutrition, intrauterine viral infection)

- Increased parental age

- Illicit substances

- Cannabis use

- City living

- Social isolation

Diagnosis

ICD-10 can be used to give a framework for diagnosis.

In patients suffering from a psychotic episode lasting for at least one month, schizophrenia may be diagnosed if one (or more) of the following is present:

- Thought echo, thought insertion or withdrawal, or thought broadcasting.

- Delusions of control, influence or passivity, clearly referred to body or limb movements or specific thoughts, actions, or sensations; delusional perception.

- Hallucinatory voices giving a running commentary on the patient’s behaviour, or discussing him between themselves, or other types of hallucinatory voices coming from some part of the body.

- Persistent delusions of other kinds that are culturally inappropriate and completely impossible (e.g. being able to control the weather, or being in communication with aliens from another world).

Or it may be diagnosed in patients suffering from a psychotic episode lasting for at least one month if two (or more) of the following are present:

- Persistent hallucinations in any modality, when occurring every day for at least one month, when accompanied by delusions (which may be fleeting or half-formed) without clear affective content, or when accompanied by persistent over-valued ideas.

- Neologisms, breaks or interpolations in the train of thought, resulting in incoherence or irrelevant speech.

- Catatonic behaviour, such as excitement, posturing or waxy flexibility, negativism, mutism and stupor.

- “Negative” symptoms such as marked apathy, paucity of speech, and blunting or incongruity of emotional responses (it must be clear that these are not due to depression or to neuroleptic medication).

There are a number of exclusions, and areas where the presentation may mimic other mental health illnesses.

The episode should not be attributable to organic brain conditions (e.g. encephalitis), or to substance misuse, intoxication, dependence or withdrawal.

Types

There are a number of subtypes differentiated by unique characteristics.

- Paranoid schizophrenia: Predominant symptom is that of what are stable, normally paranoid delusions. These are often accompanied by hallucinations (often auditory) but catatonic symptoms and those of abnormal affect, volition and speech are normally absent.

- Hebephrenic schizophrenia: Affective symptoms are prominent with abnormal behaviour. Negative symptoms are significant and social isolation may result.

- Catatonic schizophrenia: Predominant symptoms are those of psychomotor disturbance, and may exhibit both hyperkinesis and stupor as well as automatic obedience and negativism. Other features may include episodes of violent excitement.

- Undifferentiated schizophrenia: Those that meet the diagnostic threshold but do not fit into one of the above categories.

Other types include post-schizophrenic depression, residual schizophrenia and simple schizophrenia. For more information see the full ICD 10 criteria.

Investigations

It is essential that other causes of similar presentations are excluded prior to final diagnosis.

Schizophrenia is a clinical diagnosis made in the presence of characteristic features. Other conditions may cause similar presentations and these need to be excluded. Attempts should be made to rule out infection, metabolic abnormalities and organic brain disease where suspected.

In particular, there is increased interest around autoimmune encephalitis (in particular anti–NMDA receptor encephalitis) and how its presentation can mimic psychosis and schizophrenia. Typically other neurological signs develop or accompany the presentation however these can be absent.

Not all of the below investigations may be necessary and instead, they would be guided by each individual presentation, history and examination.

Bedside

- Blood sugar

- Urine dipstick (+/- MSU)

- ECG (evaluate for long QT if considering antipsychotics)

Bloods

- FBC

- LFT

- Thyroid function tests

- Syphilis serology

- Bloodborne virus screen

- Autoimmune screen (e.g. ANA, anti-DS DNA for Lupus)

Illicit drugs and alcohol

Blood, hair or urinary screens may be used for illicit drugs and alcohol, particularly in those presenting with acute psychosis of unknown cause.

Additional investigations

Depending on the presentation CT, MRI head or EEG may be ordered. Serum markers of autoimmune encephalitis can be sent as well as lumbar puncture and CSF sampling if indicated

Preventing psychosis

NICE offer guidance on preventing and anticipating psychosis.

They advise referral to specialist services in patients who are distressed with declining social function and:

- Transient or attenuated psychotic symptoms or

- Other experiences or behaviour suggestive of possible psychosis or

- A first-degree relative with psychosis or schizophrenia

Any treatment is guided by an experienced specialist but can include cognitive behavioural therapy and family interventions. Treatment for anxiety, depression and other co-existing conditions should be considered.

Overview of care

In those presenting with a new episode of psychosis, early intervention in psychosis teams are often used to co-ordinate and direct care.

Assess risk

Adult patients should be asked about suicidal thoughts and ideation as well as self-harm. This is a key part of any assessment.

In addition risk to others must be assessed. Harm may be unintentional but result in neglect or intentional (in the context of their disease).

Any patient deemed to be at risk should be discussed immediately with the local specialist mental health services for further assessment and a management plan.

Race, culture and ethnicity

Schizophrenia affects people from all races, cultures and ethnicities. Different cultural norms may result in different presentations and experiences.

Healthcare professionals should be trained and able to understand and assess people from diverse backgrounds. Experience is needed in how this may impact the experience of symptoms and treatments.

Early intervention in psychosis (EIP)

EIP teams are often the first group to review patients with a new episode of psychosis or schizophrenia.

The teams consist of psychiatrists, psychologists, community psychiatric nurses, social workers and support workers. They may continue to see the patient for up to three years.

Assessment and care planning

A full mental health history and mental state examination should be taken. Careful medical history and examination are required to reveal alternative diagnoses like organic brain disorders.

Any history of drug use or trauma should be addressed. Social networks, family life may be discussed as well as support mechanisms. Assessment should include education, occupation and economic status domains.

A care plan is made in conjunction with the patient, who should be aware of the likely diagnosis and benefits of each management plan. The care plan should include a crisis plan, advanced statement (from the patient on how they want to be treated when acutely unwell) and key contacts.

Antipsychotics

Oral antipsychotics form a key component in the management of many patients with schizophrenia.

Antipsychotics should normally be started in secondary care. They may be used in conjunction with psychological therapies or alone.

Baseline investigations

Prior to starting an antipsychotic NICE recommend the following are recorded:

- Weight

- Height

- Waist circumference

- Pulse and blood pressure

The following assessments should be recorded:

- Assessment of any movement disorders

- Assessment of nutritional status, diet and level of physical activity

In addition, the following blood tests are advised:

- Fasting blood glucose

- HbA1c

- Blood lipid profile

- Prolactin levels

An ECG should be organised in patients depending on antipsychotic choice (some are associated with long QT), history or examination findings suggestive of cardiovascular disease or the patient is being admitted to hospital.

Typical and atypical

There are two generations of antipsychotics, often referred to as typical and atypical.

- Typical antipsychotics (first generation): Developed back in the 1950’s, they act via the blockade of dopamine receptors (D2). Commonly used examples include haloperidol and chlorpromazine. They can cause a number of significant side effects. Extrapyramidal side effects may occur resulting in dystonia and tremor. Tardive dyskinesia, which refers to uncontrolled repetitive movements such as smacking lips together, may develop with prolonged use. Agranulocytosis and bone marrow suppression may occur.

- Atypical antipsychotics (second generation): Block dopamine receptors (D2), and many act on serotonin receptors. Commonly used examples include clozapine and olanzapine. Extrapyramidal side-effects and tardive dyskinesia are less common, however, they are associated with significant weight gain and insulin resistance. Agranulocytosis and bone marrow suppression may occur.

Many prescription, over the counter and illicit drugs can interfere with antipsychotics and this should be reviewed. In particular, smoking can impact the efficacy of antipsychotics (particularly clozapine and olanzapine) and discussions regarding cessation should be had.

Choice

NICE advise that starting antipsychotics should be considered an ‘explicit individual therapeutic trial’. It does not determine that one drug or generation should be used in particular but instead, the individual merits and side effects should be discussed with each patient, and a collective decision reached.

Doses tend to be chosen from the lower end of the licensed range and gradually titrated upwards. Close monitoring is required to pick up developing side effects and the following monitoring is also advised:

- Weight: every week for 6 weeks, then every 12 weeks, then at 1 year, then annually (plot on graph).

- Waist circumference: measure yearly (plot on graph).

- Pulse and blood pressure: measure at twelve weeks, then at 1 year, then annually.

- Fasting glucose, HbA1c, blood lipids: at 12 weeks, then at 1 year, then annually.

NICE does advise the use of clozapine if the patient has failed to respond adequately to 2 different antipsychotics (one of which is an atypical antipsychotic that is not clozapine). The risk of neutropenia and agranulocytosis is high and close monitoring (and regular FBCs) is required.

Depot / long-acting injectable

Antipsychotics can be given as a depot or long-acting injectable. They may be used when it is the patient’s preference or where avoiding covert non-adherence is ‘a clinical priority within the treatment plan’.

Stopping medication

Once stabilised on an antipsychotic, treatment cessation is associated with an increased risk of relapse. In particular NICE advises there is a high risk of relapse if treatment is stopped in the first 1-2 years.

If the decision is made to stop the antipsychotic, this should be a supervised gradual withdrawal. Patients need to be followed up for signs of relapse for at least 2 years after stopping medication.

Psychological therapies

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and family interventions may help those suffering with schizophrenia.

CBT should be offered to all patients and can be commenced in the acute phase. Family interventions should be offered to all families who live with or are in close contact with the patient. In addition many find art therapies beneficial.

- Individual CBT: normally consists of at least 16 one-on-one sessions. CBT aims to help patients explore their conditions. It looks to help patients create links between their thoughts, feelings and actions with their experience of schizophrenia. Patients are encouraged to re-evaluate how their perceptions may relate to symptoms.

- Family intervention: should include the patient suffering from schizophrenia if possible as well as their main carer. Normally consists of 10 sessions over 3 months – 1 year.

Patients are normally advised to use psychological therapies in conjunction with an antipsychotic. Some may want to use them independently (CBT or family intervention), in this setting NICE advise:

- Review within one month, to discuss options including antipsychotics

- Regular monitoring of symptoms and well-being.

Prognosis

Schizophrenia is a chronic disease that has a fluctuating and varied course.

Following treatment of an acute psychotic episode, most will experience a significant improvement in their positive symptoms. However negative symptoms can be extremely troublesome and difficult to treat. The majority of patients will have further acute psychotic episodes, though treatment can reduce the frequency.

A number of factors are associated with a poor prognosis, including substance abuse, early-onset, poor treatment adherence, poor cognitive skills and certain genetics.

Around 10-15% have persistent psychotic features following on from an acute episode. They may require institutional care and those with schizophrenia die, on average, 9-15 years earlier than the general population. The lifetime risk of suicide is increased and estimated at 5%. In addition patients are more likely to suffer with T2DM, cardiovascular disease and have negative lifestyle factors like smoking and poor diet.