Introduction

Glaucoma refers to a collection of disorders resulting in progressive optic neuropathy in which raised intraocular pressure is typically a key factor.

Glaucoma

Glaucoma is a common pathology affecting the eye that untreated can result in significant loss of vision. Worldwide it is the leading cause of irreversible blindness with 66 million affected, 12.5 million of whom are blind. In the UK it is responsible for around 10% of those registered blind. There are two major forms of glaucoma (and a related condition ocular hypertension):

- Open-angle glaucoma: characterised by a normal angle between the iris and cornea. It is divided into primary and secondary forms. Primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) is the most common form of glaucoma. Raised intraocular pressure (IOP) is normally but not invariably present, some with POAG have ‘normal pressure glaucoma’.

- Angle-closure glaucoma: characterised by closing or narrowing of the angle between the iris and cornea. Again can be split into primary and secondary forms, though primary is far more common. The closure of the anterior chamber angle results in reduced drainage of the aqueous humour and rising IOP.

- Ocular hypertension: refers to elevated IOP without the presence of other changes seen in glaucoma. May represent an opportunity to offer early treatment and prevent the development of visual loss. IOPs greater than 21 mmHg are generally said to be raised.

Angle-closure glaucoma

In this note we focus on angle-closure glaucoma. Though less common than open-angle glaucoma, it causes around 50% of cases of glaucoma-related blindness. It may be classified as acute or chronic with differing presentations:

- Acute angle-closure glaucoma: is an ophthalmic emergency that presents with severe eye pain, visual loss, redness, headache, nausea and vomiting.

- Chronic angle-closure glaucoma: onset is often insidious with visual loss only apparent in advanced disease. Normally picked up in otherwise asymptomatic patients on routine ophthalmic examination.

As described above angle-closure glaucoma can also be divided into primary angle-closure glaucoma (PACG) and secondary angle-closure glaucoma (when it occurs secondary to another eye condition). PACG is by far the more common form.

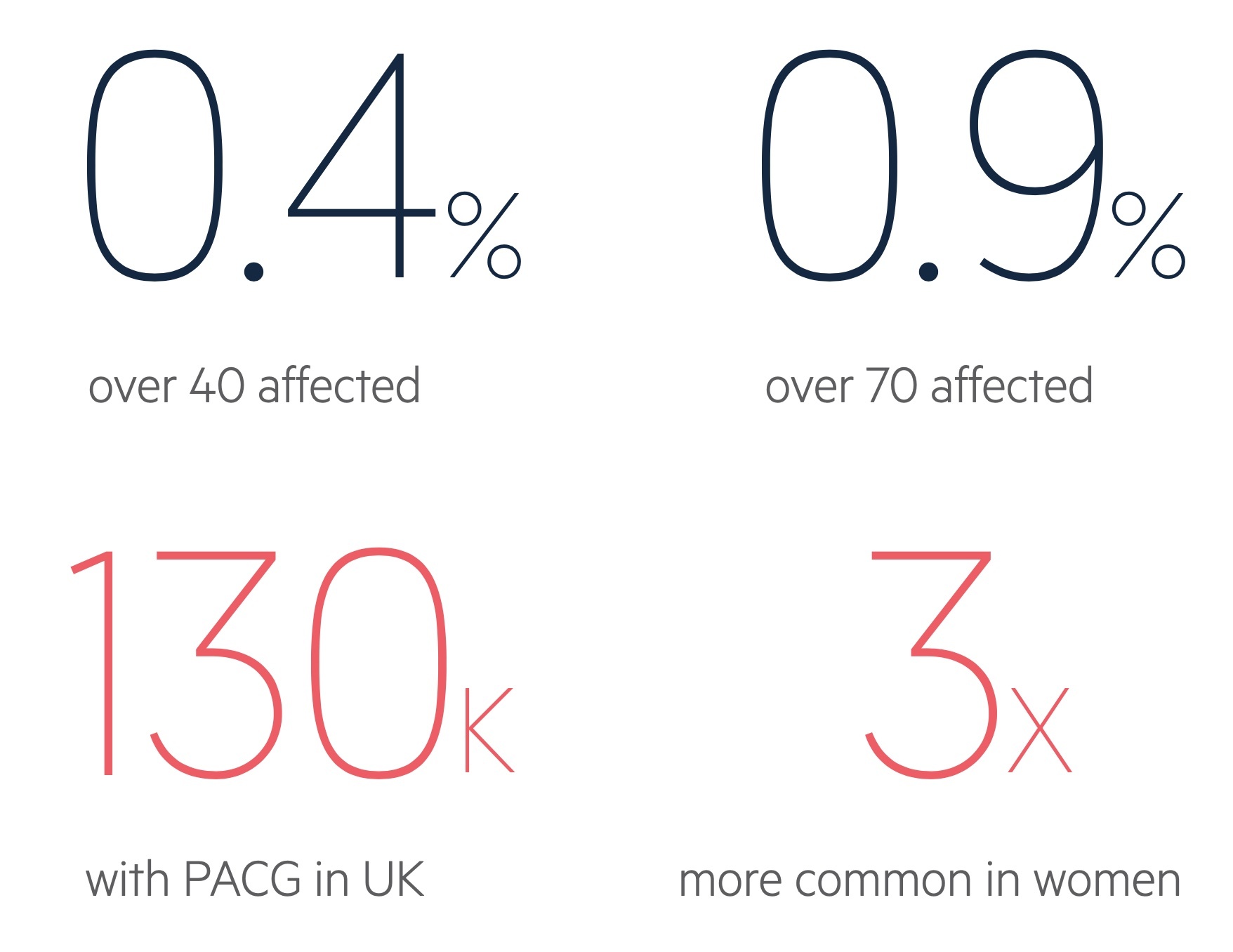

Figures from the diagram are for PACG, taken from NICE CKS (last accessed Nov 2021).

Epidemiology

Primary-angle closure glaucoma affects around 0.4% of those over the age of 40 in the UK.

It becomes increasingly common with advancing age. The condition is around 2-4 times more common in women.

Those of Asian and Inuit heritage are more commonly affected with prevalence highest in China.

Risk factors

Women are 2-4 times more likely to be affected than men.

There are a number of risk factors for angle-closure. Interestingly some differ to open-angle glaucoma with hyperopia (as opposed to myopia) and those of Asian and Inuit heritage (as opposed to Black African) more likely to be affected.

- Age

- Ethnicity (highest rate in people of Asian and Inuit heritage)

- Family history

- Gender (females are 2-4 times more affected)

- Hyperopia

- Anticholinergic topical drops (i.e. pupil dilators)

- Systemic medications (e.g. antimuscarinic or adrenergic medications)

Aqueous humour

Aqueous humour is produced by epithelium covering the ciliary bodies in the posterior chamber of the eye.

Basic anatomy

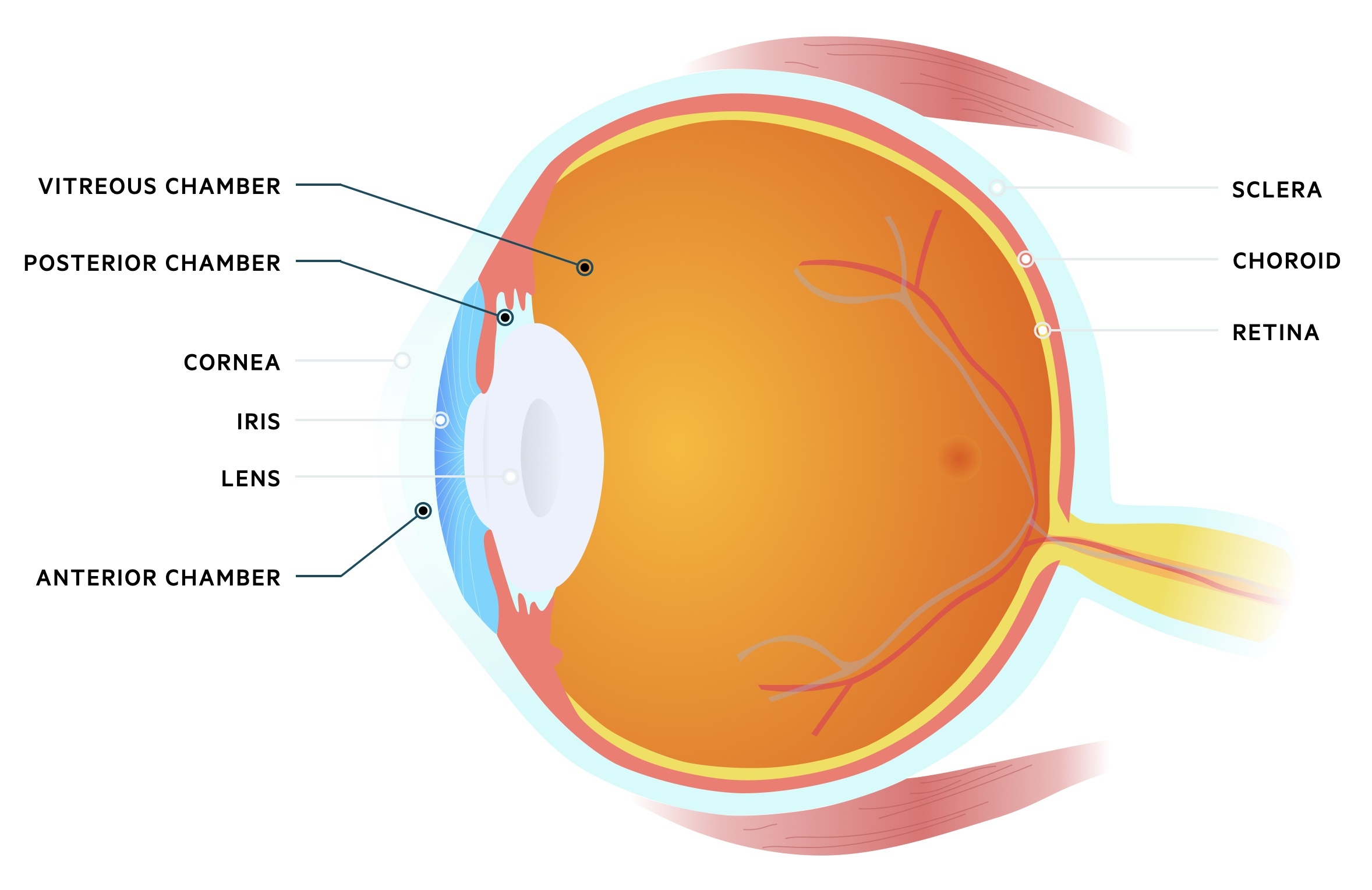

The eye may be divided into three chambers:

- Anterior chamber: located anteriorly between the cornea and iris. Filled with aqueous humour that flows from the posterior chamber.

- Posterior chamber: located behind the anterior chamber, between the iris and lens. Aqueous humour is produced here by the ciliary epithelium.

- Vitreous chamber: located behind the posterior chamber between the lens and back of the eye. Filled with vitreous humour, a fluid with a gel-like consistency.

Production & drainage

The aqueous humour is produced and actively secreted by the ciliary epithelium located in the posterior chamber of the eye. It is a watery fluid with a similar make-up to plasma though with a far lower protein content.

NOTE: Inflammation of the uvea can lead to increased membrane permeability and therefore protein content in the aqueous humour. This can scatter light resulting in flare.

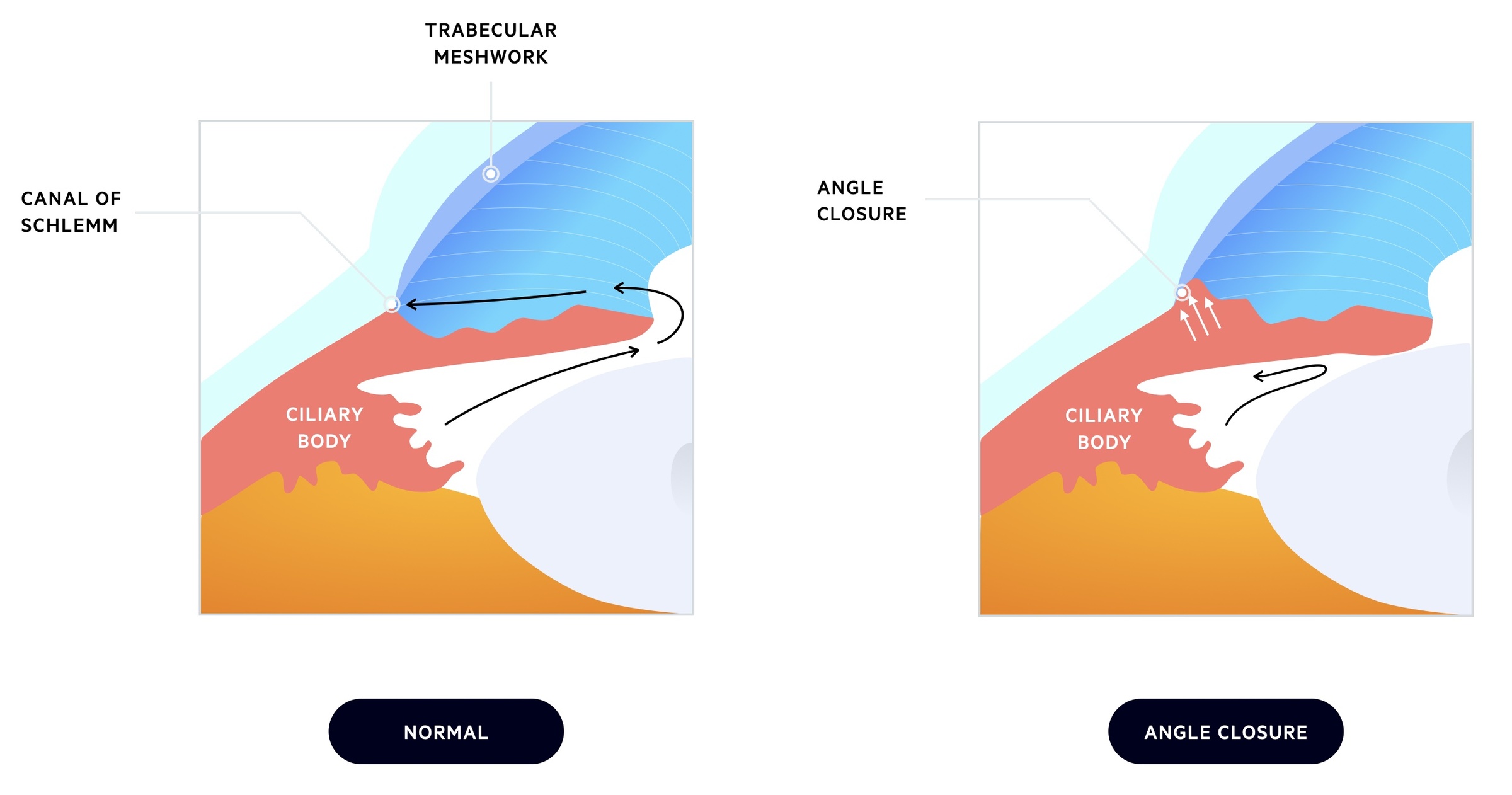

The aqueous humour passes through the pupil into the anterior chamber and drains at the anterior chamber angle (iridocorneal angle). There are two drainage pathways:

- Canal of Schlemm: the majority of aqueous humour drains via the trabecular meshwork into the canal of Schlemm.

- Uveoscleral pathway: some of the aqueous humour may drain via the ciliary muscle into the supraciliary and suprachoroidal spaces.

Pathophysiology

Angle-closure glaucoma may be primary (anatomical predisposition) or secondary (occurring due to another eye pathology).

Primary angle-closure glaucoma

In PACG patients are anatomically predisposed to the development of the condition. The lens is located anteriorly and presses against the iris. This interrupts normal flow through the chambers with pressure building in the posterior chamber behind the iris. As the iris pushes forward it closes the anterior chamber angle.

Contact with the iris leads to scar tissue formation within the trabecular meshwork further reducing drainage.

PACG may be acute, subacute or chronic:

- Acute: complete blockage of the anterior chamber angle resulting in a rapid rise in IOP. Results in acute symptoms of eye pain, vision loss, redness, headache and vomiting. This is an ophthalmological emergency requiring urgent treatment.

- Subacute: closure of the angle results in acute symptom development but follows a self-limiting and recurrent pattern.

- Chronic: incomplete closure or scarring reduces drainage of aqueous humour but does not cause as sudden and high rises in IOP. It is often asymptomatic and be picked up incidentally or in advanced disease when vision loss is noted.

Secondary angle-closure glaucoma

Secondary angle-closure glaucoma results from other pathology in the eye that result in angle-closure – they are far less common than PACG.

The causative pathologies can be divided into conditions that ‘push’ the iris/ciliary body (e.g. space-occupying lesion) or those that ‘pull’ the iris causing deformity (e.g. neovascularisation of iris).

Clinical features

Angle-closure glaucoma may present with acute severe eye symptoms or have a chronic and insidious onset.

The symptoms experienced by the patient depend on the degree of angle closure and the extent and speed with which IOP rise.

Acute

Patients with acute angle-closure glaucoma present with acute and severe symptoms. They may have a history of previous similar episodes that resolved.

History may reveal a precipitating factor such as a topical pupil dilator or watching television in a darkened room. Features include:

- Severe eye pain

- Red eye

- Semi-dilated and fixed pupil

- Visual loss

- Halos

- Headache

- Nausea & vomiting

Image showing red right eye with semi-dilated pupil

Image courtesy of J.Heilman

Chronic

Patients with chronic disease are normally asymptomatic. Similar to POAG it may be picked up on routine ophthalmic examination.

Others may present with advanced disease when visual loss becomes noticeable to the patient.

Investigations

Acute angle-closure glaucoma should be suspected in patients presenting with a painful red eye and visual disturbance.

Investigations are dependent on the presentation. Acute angle-closure glaucoma is normally suspected based upon the clinical presentation. Diagnosis may be made with:

- Tonometry: this enables measurement of intraocular pressure (IOP). Normal pressure is 8-21 mmHg. In AACG pressures are often very high (e.g. ≥ 30 mmHg).

- Gonioscopy: should be performed in all patients with suspected angle-closure glaucoma. Allows assessment of the anterior chamber and the internal drainage system.

- Ophthalmoscopy/slit lamp: may show changes consistent with glaucoma such as ‘cupping’. This refers to an increase in the optic disc that is taken up by the central ‘cup’.

Further investigations may include ultrasound biomicroscopy and optical coherence tomography.

Opportunistic testing

There is no formal screening programme for glaucoma.

Despite this there are a number of ways signs indicative of glaucoma can be picked up in otherwise asymptomatic patients. This is of course not relevant for patients with acute symptomatic presentations. NICE CKS advise the following groups are considered for review by optometrists:

- Elderly: from the age of 60 eye exams every two years until 70, then yearly after that. Free exams are available on the NHS for this group.

- Family history: those over the age of 40 with an affected first-degree relative should have yearly eye exams. Free exams are available on the NHS for this group.

- Ethnicity: those of black African heritage over the age of 40. Free exams are not available on the NHS for this group. An ophthalmologist may however state an individual is at risk of glaucoma, thereby entitling them to free eye examinations.

Acute angle-closure

Acute angle-closure glaucoma is an ophthalmic emergency requiring immediate ophthalmology input and management.

Initial management

The aim of initial therapy is to reduce the IOP, improve symptoms and preserve sight. In addition to the medication that reduces IOP, antiemetics and analgesics may be required.

A number of medical therapies can be used:

- Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (e.g oral – Acetazolamide, topical – Brinzolamide): cause a reduction in the secretion of the aqueous humour and therefore reduction in IOP.

- Topical beta-blocker (e.g Timolol): these reduce IOP by lowering the production of aqueous humour.

- Topical sympathomimetics (e.g Brimonidine tartrate): these reduce IOP by lowering the production of aqueous humour and increasing uveoscleral outflow.

- Topical pilocarpine: cause pupillary constriction, that thins the iris and pulls it away from the trabecular meshwork. Darker pigmented eyes may need higher dosing.

- Hyperosmotic agents (e.g. Mannitol): reduce IOP through the extraction of fluid from the aqueous humour. Typically only used in the setting of failure of other agents.

If medical management fails, anterior chamber paracentesis (direct fluid removal) may be performed to ensure resolution.

Definitive management

After the initial presentation has been managed a definitive treatment, aimed at creating a persistent open-angle is required.

Laser peripheral iridotomy involves creating an opening in the iris. This allow equalisation between the posterior and anterior chambers thereby preventing a build-up of pressure in the posterior chamber. Typically treatment will also be advised in the contralateral eye which is also at risk of angle-closure.

Chronic angle-closure

Chronic angle-closure glaucoma is often treated with laser peripheral iridotomy.

Laser peripheral iridotomy can be used in patients with chronic angle-closure glaucoma. Again it resolves ‘pupillary block’ as it allows equalisation between the posterior and anterior chambers thereby preventing a build-up of pressure in the posterior chamber.

Treatment failure can occur, especially if there is significant scarring of the trabecular meshwork from the previous apposition with the iris. Treatment is then similar to that of open-angle glaucoma.

Prognosis

Angle-closure glaucoma is responsible for 50% of the glaucoma-related blindness in the world.

This translates to around 6.25 million people, despite being less common than the open-angle form. If recognised and promptly treated the prognosis is good but the insidious nature of the chronic form and lack of access to advanced healthcare often leads to poor outcomes.

40-80% of patients with an acute angle-closure glaucoma will have an episode in the contralateral eye in the following 5-10 years. As such after an acute episode in one eye, definitive treatment is advised in the other.