Overview

Endometriosis refers to the extrauterine implantation and growth of endometrial tissue.

It is often a chronic and debilitating condition that is likely under-recognised and often diagnosed after repeated presentation. Like endometrial tissue in the uterus, endometriosis responds to cyclical hormones leading to inflammation, bleeding and scaring.

The deposits are most frequently on pelvic structures – with the ovaries most affected – though they may also occur on extra-pelvic structures (on rare occasions even in the pleural cavity or brain). It commonly causes pain but may also lead to reduced fertility and the formation of adhesions.

Two specific terms to be aware of are:

- Adenomyosis: Specifically refers to deposits of endometrial tissue in the myometrium of the uterus.

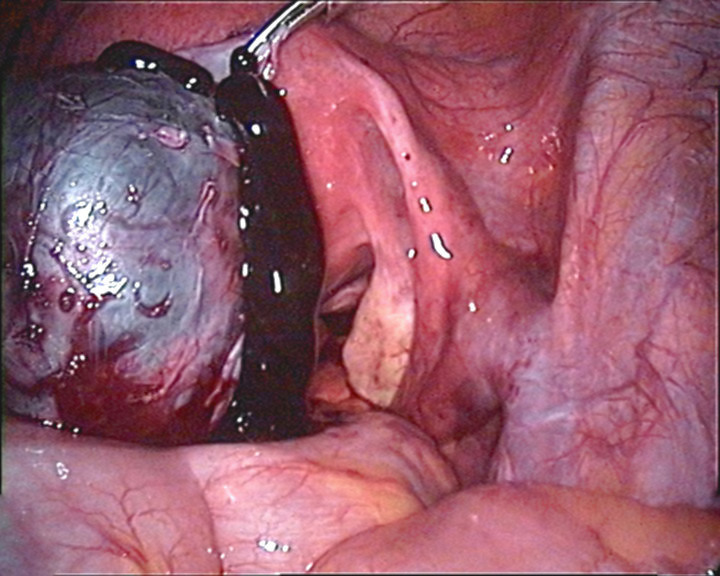

- Endometrioma: Cystic structures developing on the ovaries in endometriosis. They are frequently referred to as chocolate cysts due to the appearance of the contained, old and altered blood.

A perforated endometrioma seen on laparoscopy

Epidemiology

Exact incidence is difficult to ascertain as laparoscopy is considered the diagnostic standard and many may have sub-clinical or unrecognised disease.

Figures from Endometriosis UK estimates it affects 10% of women in their reproductive years. That correlates with an estimated 176 million women worldwide.

In women with infertility the prevalence is likely significantly higher, and may affect up to 50%.

Aetiology

The cause of endometriosis is unknown, though numerous theories exist.

One of the earliest theories involved retrograde menstruation. This was the idea that some endometrial tissue exited via the fallopian tubes during menstruation. Whilst this certainly appears to occur relatively commonly, it is not clear this causes endometriosis. This does not explain why endometriosis may occur following hysterectomy and in (very) rare cases men on prolonged hormonal therapy.

Metaplastic conversion of other tissues has been suggested and could explain why deposits may be seen in seemingly anatomically distinct positions.

Lymphatic or hematogenous spread has also been suggested for one of the means by which endometriosis may develop in remote regions of the body.

Risk factors

A number of factors have been identified as increasing the risk of endometriosis.

- Early menarche

- Late menopause

- Nulliparity

- Delayed childbearing

- Short menstrual cycle

- Family history

- White ethnicity

Clinical features

It is estimated the average time from presentation to formal diagnosis is 7.5 years.

- Chronic pelvic pain

- Dysmenorrhoea

- Irregular periods

- Dyspareunia

- Dyschezia (often cyclical)

- Bloating, nausea (often cyclical)

- LUTS (often cyclical)

- Infertility/sub-fertility

Rarely endometriosis may present with symptoms of distant deposits. These can be exceedingly rare (and under recognised) causing seemingly incongruous presentations including catamenial pneumothorax and catamenial epilepsy.

Referral

Management of endometriosis often relies on input from both primary and secondary care.

Referral is normally advised for USS (if not already completed) and gynaecological review for women with:

- Severe, persistent, or recurrent symptoms of endometriosis.

- Pelvic signs off endometriosis.

- Management in primary care is not effective.

- Fertility issues

Referral to specialist endometriosis service is recommended in patients with confirmed or suspected deep endometriosis affecting the bowel, bladder or ureter.

Secondary care follow-up is advised in those declining surgery with confirmed deep endometriosis or an endometrioma > 3cm.

Investigations

Laparoscopy is considered the gold-standard in the diagnosis of endometriosis.

USS, MRI and laparoscopy may all be used in the investigation and diagnosis of endometriosis. Additional investigation to exclude urinary and sexually transmitted infections may also be organised.

USS

USS may be carried out as an initial investigations and is capable of identifying likely endometriosis as well as excluding other causes of presentation.

The preferred approach is transvaginal, though transabdominal can be used when not appropriate. Endorectal USS may also be used.

MRI

MRI is not typically the first line investigation. It may be used in those with suspected deep endometriosis, particularly affecting the bowel, bladder or ureter.

Laparoscopy

Laparoscopy is an invasive procedure, requiring a general anaesthetic. When indicated, it is considered the primary diagnostic modality. It may diagnose disease not seen on USS.

During surgery a systematic review of pelvic structures is conducted. Histology samples are taken from suspected endometriosis deposits.

Conservative care

Pain relief and hormonal therapies may help with the symptoms of endometriosis.

Pain management

Analgesia, as a limited trial may be given. Paracetamol and/or NSAIDs (in absence of relevant contraindications) can be used.

Hormonal therapies can significantly reduce the pain experienced by some women. Options include combined oral contraceptive pill, progesterone only pill, the implant and the Mirena coil. These are of course not an option if the women is trying to conceive.

Supporting individual needs

Each patient will have different experiences and healthcare needs. Depression and anxiety may be caused or exacerbated by the features and diagnosis of endometriosis. This should be recognised and treated as is appropriate.

Surgical management

Surgery may be indicated in those with endometriosis.

Often the diagnostic laparoscopy will also be used for therapeutic intervention following appropriate discussion with the patient. In particular peritoneal endometriosis and uncomplicated endometriomas may be treated. Excision or ablation can be used. Hormonal treatment may be advised to sustain the benefit from surgery or help with persistent symptoms.

For those with endometriosis affecting the bowel, bladder or ureter, 3 months of gonadotrophin-releasing hormone agonists may be given pre-operatively.

Hysterectomy may be performed in combination with surgical management, normally in patients with significant menorrhagia or adenomyosis that have not responded to more conservative measures.

Fertility

Infertility/sub-fertility is common in women suffering with endometriosis. Management should involve a relevant MDT with input from fertility specialists. This may involve the standard infertility work-up and fertility treatments. In endometriosis a number of surgical procedures may improve chances of spontaneous pregnancy.

NICE guidelines advise ‘offer excision or ablation of endometriosis plus adhesiolysis for endometriosis not involving the bowel, bladder or ureter, because this improves the chance of spontaneous pregnancy.’

Endometriomas are known to affect fertility and NICE advise ovarian cystectomy with excision of the cyst wall. This has been shown to increase the chance of spontaneous pregnancy and reduce recurrence of an endometrioma. Prior to this a women ovarian reserve should be considered.

In women with deep endometriosis involving the bowel, bladder or ureter – a discussion between the specialist and a patient may be had. Each case should be looked at independently with discussion of non-operative options, possible benefits of surgery and the impact of potential complications.

Prognosis

Endometriosis takes a varied and unpredictable course.

It may remain a debilitating condition throughout a women’s reproductive years, progress and worsen or spontaneously regress.

Most women find hormonal therapies help them manage their symptoms. Some require surgery – though it is important to note recurrence is relatively common (estimated at 10-50% at one year) and can even occur after hysterectomy.

After menopause endometriosis is very rare as oestrogen levels fall, but may be seen on certain hormone treatments (e.g. HRT).