Introduction

Potassium is an essential body cation, which has a normal plasma concentration of 3.5-5.5 mmol/L.

Hypokalaemia is one of the most common electrolyte abnormalities within the hospital setting. It is defined as a plasma potassium concentration < 3.5 mmol/L. Hypokalaemia can be a potentially life-threatening condition leading to dangerous cardiac arrhythmias, although most cases are mild and patients are asymptomatic.

Hypokalaemia can be further divided as follows:

- Mild: 3.0-3.4 mmol/L

- Moderate: 2.5-2.9 mmol/L

- Severe: < 2.5 mmol/L or symptomatic

Epidemiology

Hypokalaemia is a common electrolyte abnormality in secondary care affecting up to 20% of inpatients.

Potassium concentration is highly variable depending on age, sex, ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Low potassium levels are further affected by intercurrent illness, medications (e.g. non-potassium sparing diuretics), and co-morbidities (e.g. heart failure, nephrotic syndrome, alcoholism).

Often, patients with hypokalaemia have a number of medical problems making the identification of the exact cause(s) of hypokalaemia difficult.

Physiology

Potassium is primarily an intracellular cation. Approximately 98% of potassium within the body is found within cells.

An adult has approximately 3,500 mmol of potassium. In the normal individual, a daily intake of 90 mmol/day is recommended by the World Health Organisation.

Cellular uptake of potassium is controlled by sodium-potassium adenosine triphosphatase pumps (Na+/K+ATPase). Its action is stimulated by (amongst others) sympathetic stimulation and insulin. Acidosis results in decreased cellular uptake of potassium as it is released in exchange for hydrogen ions.

Potassium is excreted by renal and extrarenal methods. Renal excretion is most significant, accounting for up to 90% of excretion.

Aetiology

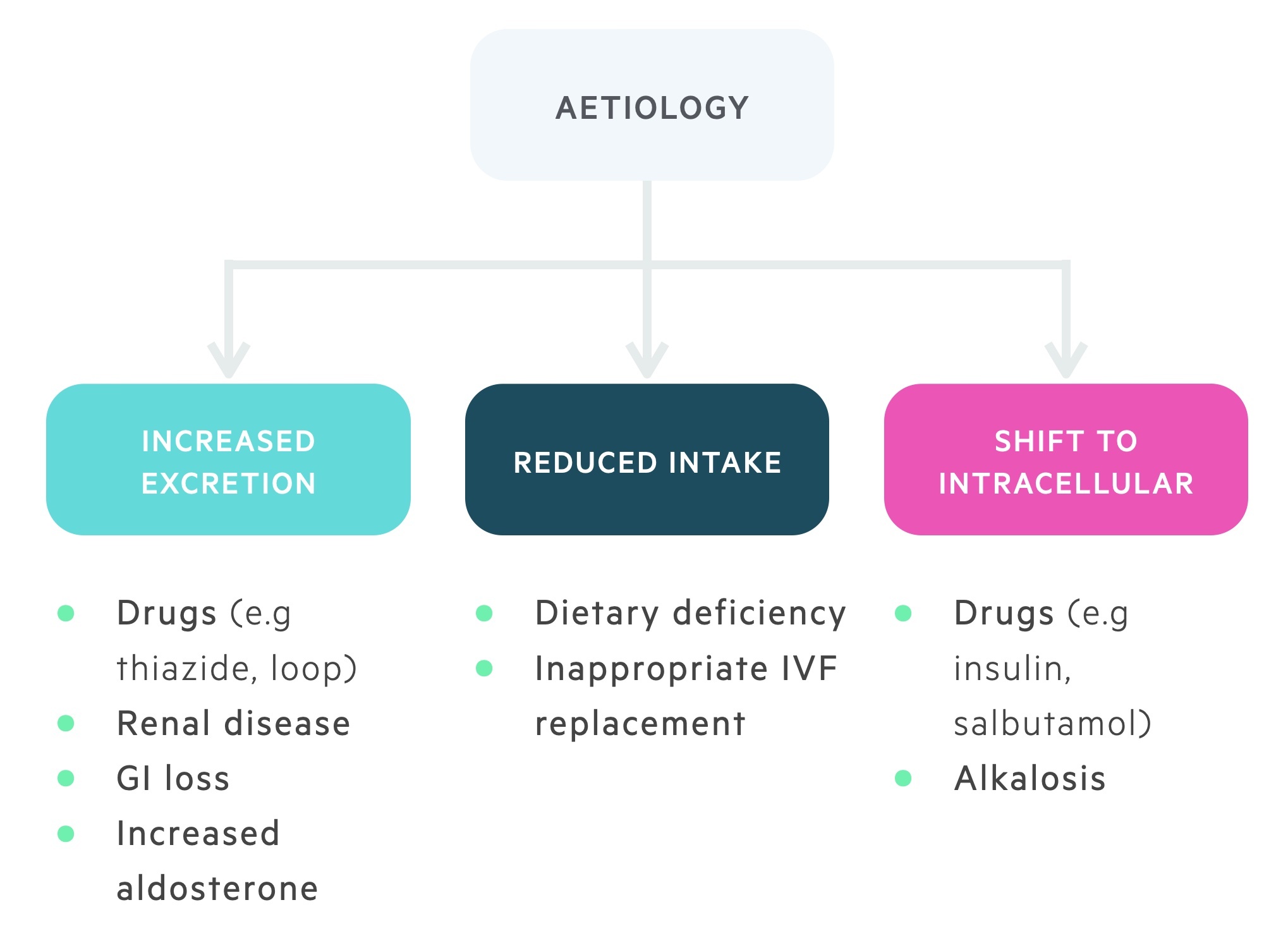

Hypokalaemia may be caused by inadequate intake, increased excretion or transcellular shift.

Inadequate potassium intake

Poor intake of potassium by itself is an uncommon cause of hypokalaemia. It normally contributes in combination with other mechanisms (as detailed below)

The main causes of inadequate potassium intake include:

- Eating disorders: bulimia, anorexia nervosa, alcoholism

- Poor diet

- Systemic illness and dental problems

- Inadequate potassium in feed or fluid replacement (IVF, NG feed, TPN)

Increased potassium excretion

Increased excretion of potassium can occur via the renal system, gastrointestinal tract or skin:

- Renal: diuretics (thiazide-like & loop), other drugs, mineralocorticoid excess, genetic

- Gastrointestinal: diarrhoea, vomiting, villous adenoma, laxative abuse

- Skin: burns, erythroderma, hyperhidrosis

In clinical practice, hypokalaemia is frequently seen secondary to diuretics (e.g. loop, thiazide) or gastrointestinal losses (e.g. diarrhoea and/or vomiting).

Genetic causes of increased renal excretion of potassium are uncommon, however, a basic appreciation of these conditions is useful.

Bartter’s syndrome: Refers to a group of autosomal recessive conditions characterized by hypokalaemia, alkalosis, and hypotension or normotension, related to genetic variants in genes encoding proteins in the loop of Henle.

Gitelman’s syndrome: Is an autosomal recessive condition characterised by hypokalaemia, hypomagnesaemia, alkalosis, and hypotension or normotension, related to a genetic variant in a gene encoding the thiazide-sensitive sodium chloride transporter.

Liddle’s syndrome: Is an autosomal recessive condition characterised by hypokalaemia and hypertension, related to genetic variants in genes encoding the subunits of the epithelial sodium channel.

Transcellular shift in potassium

Potassium is predominantly an intracellular cation, but certain conditions increase the chance of potassium shifting from the extracellular to intracellular space.

Alkalosis, the glycoregulatory hormone insulin and activation of beta-adrenergic receptors (e.g. salbutamol) enhance the intracellular movement of potassium.

Clinical features

Most cases of hypokalaemia are mild and asymptomatic.

If symptoms do develop the most common are non-specific weakness and fatigue.

Symptoms

- Fatigue

- Generalised weakness

- Muscle cramps & pain

- Palpitations

- Constipation

Signs

- Arrhythmias

- Muscle paralysis & rhabdomyolysis (severe)

NOTE: It is important to evaluate for features of the underlying aetiology.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of hypokalaemia is based on a laboratory sample of plasma potassium <3.5 mmol/L.

The severity can be divided as follows:

- Mild: 3.0-3.4 mmol/L

- Moderate: 2.5-2.9 mmol/L

- Severe: < 2.5 mmol/L or symptomatic

In addition, attention should be given to the velocity and extent of any decline (if serial measurements are available). Other investigations that may be important in the workup of hypokalaemia are as follows.

- ECG (see below)

- Urine osmolality

- Urinary electrolytes (sodium & potassium)

- Full blood count

- U&Es, bone profile, magnesium

- VBG/ABG (can assess acid/base, bicarbonate & chloride, also gives a rapid potassium result)

- CK

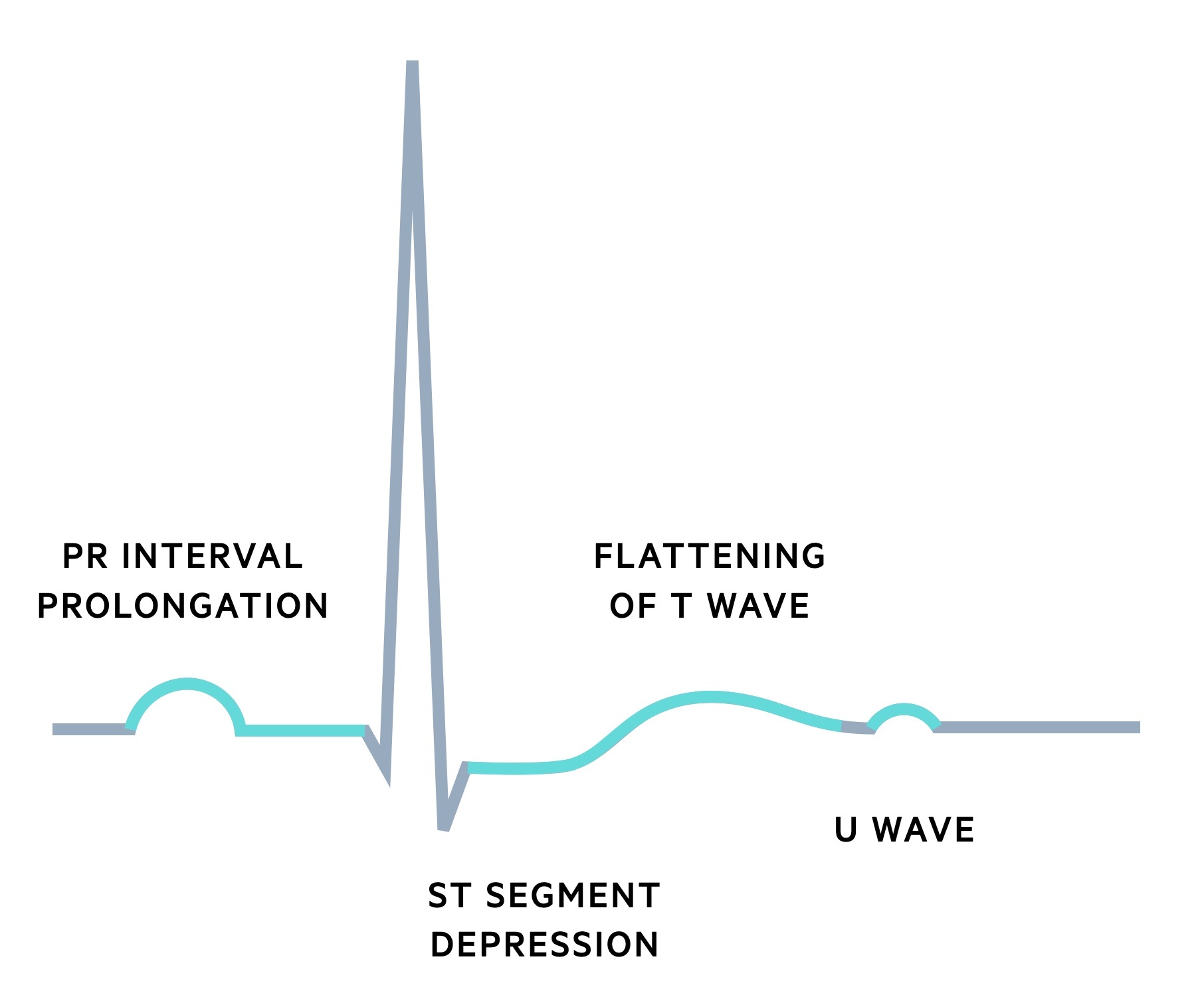

ECG

Hypokalaemia can lead to potentially dangerous cardiac arrhythmias.

All patients with moderate-to-severe hypokalaemia should have an ECG. The ECG may be entirely normal.

High-risk patients should also have an ECG regardless of potassium level. In patients on digoxin, hypokalaemia increases the risk of toxicity and related changes may be evidenced on an ECG.

Typical ECG changes associated with hypokalaemia include:

- Flat T waves

- ST depression

- Prominent U waves

- Prolonged PR

A U wave is a small deflection that occurs following the T wave, typically in the same direction.

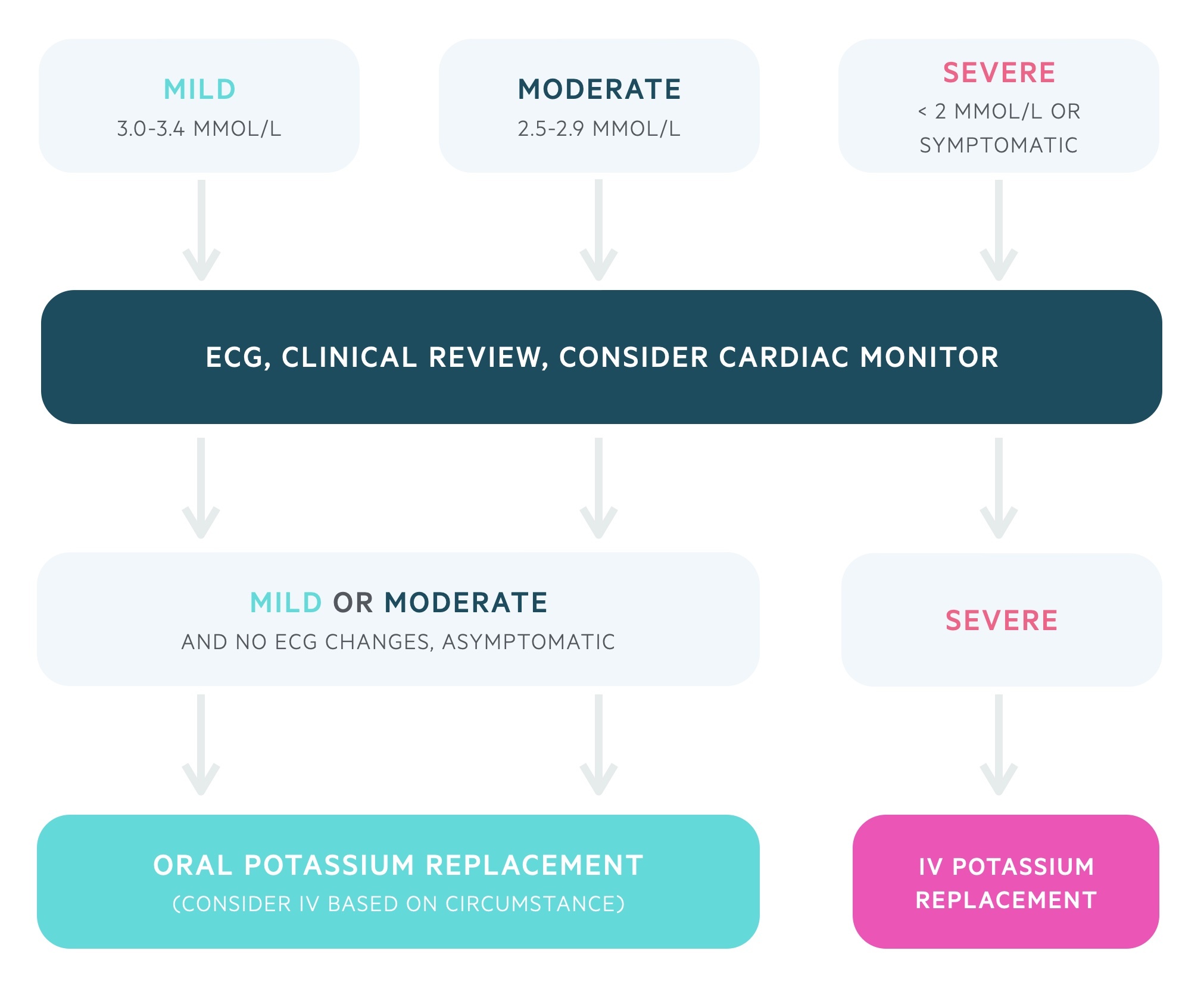

Management

Potassium may be replaced via oral or intravenous routes.

Patients with hypokalaemia require a clinical (including a thorough fluid status assessment) and prescription chart review to help identify the underlying aetiology. Other electrolyte abnormalities, magnesium in particular, should be identified and replaced.

All patients with moderate or severe hypokalaemia should have a 12 lead ECG. An ECG should also be ordered in those with co-morbidities and those with a rapid or large drop in their potassium levels. Patients with ECG changes require senior review, a peri-arrest or arrest call should be made for those with unstable arrhythmias.

Mild to moderate hypokalaemia

In patients with mild to moderate hypokalaemia the oral replacement route is generally preferred. Refer to local guidelines for dosages. Intravenous replacement may be used with appropriate caution depending on the circumstances (e.g. a patient who is nil by mouth).

An example would be SANDO-K (potassium chloride with potassium bicarbonate), two tablets, three times a day. Each SANDO-K tablet contains 12 mmol of K+ and 8 mmol of Cl–. Patients should have regular repeat blood tests.

Severe hypokalaemia

Patients with severe hypokalaemia or who are symptomatic require intravenous replacement typically with 40 mmol of KCL in 1 litre of normal saline. The maximal rate on a normal ward is 10 mmol of potassium an hour. A repeat blood test should be sent after each bag of replacement.

It may be necessary to give more concentrated replacement (e.g. 40 mmol KCL in 500ml of normal saline or 10 mmol KCL in 100 mls of normal saline) or more rapid replacement. This should only be done under the guidance of a senior physician in compliance with local guidelines, normally in an HDU/ITU setting.