Introduction

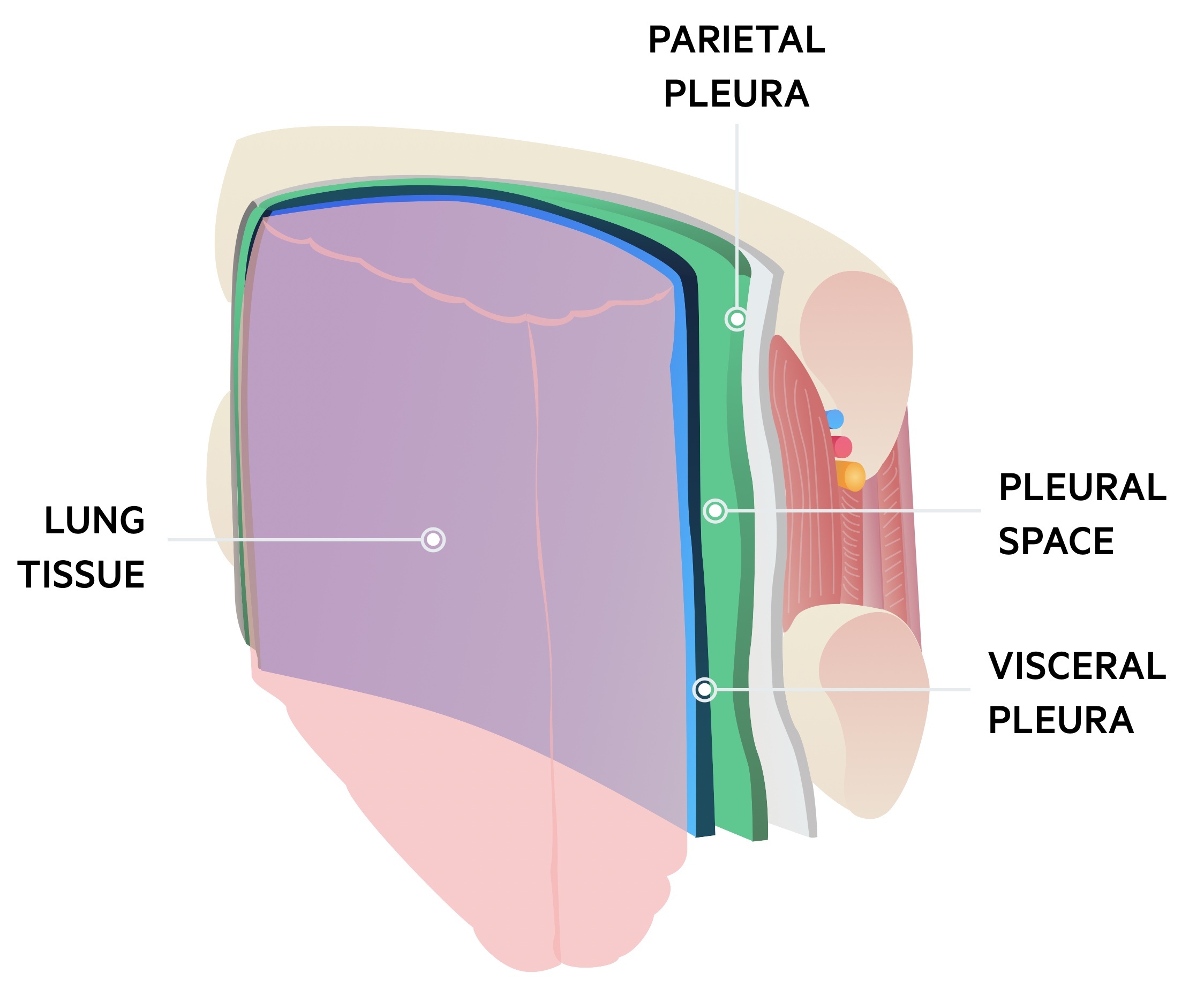

A pneumothorax is a collection of air within the pleural space.

The pleural space (or cavity) refers to the space between the parietal (lines the inner wall of the lung) and visceral pleura (lines the surface of the lung). When air enters this space it is referred to as a pneumothorax.

There are two major types of pneumothorax:

- Spontaneous: occurring without prior trauma, normally in older patients with underlying lung disease or younger patients with apical blebs.

- Traumatic: occurring in the setting of trauma, may be open (direct communication between the outside air and pleural space) or closed.

Aetiology

Spontaneous pneumothoraces may be either primary or secondary

First described in the early nineteenth century, pneumothorax was most commonly seen in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis.

Today in the UK pulmonary TB is relatively rare, instead, other forms of lung disease are related to a pneumothorax (secondary). It may also be seen in patients with healthy lungs (primary):

- Primary spontaneous pneumothorax (PSP) – occur spontaneously in a previously non-pathological lung; typically seen in tall, thin young men.

- Secondary spontaneous pneumothorax (SSP) – occur in previously diseased lungs; common causes include COPD and asthma.

It is thought that in both types the underlying mechanism is due to the rupture of lung blebs and bullae. These are small pockets of air that form within the lung parenchyma.

Clinical features

Pneumothorax classically presents with sudden onset pleuritic chest pain and dyspnoea.

The clinical features of pneumothorax typically develop at rest but can occur during exercise, air travel, scuba diving, or with the use of illicit drugs. Symptoms are typically unilateral since the development of pneumothorax is most commonly unilateral. Bilateral pneumothorax is rare (particularly spontaneous).

Symptoms

- Dyspnoea: mild to severe

- Pleuritic chest pain: pain worse on deep inspiration. Usually unilateral

Signs

- Normal: particularly for small pneumothoraces

- Tracheal deviation: away from the side of the pneumothorax (late sign)

- Reduced chest expansion

- Reduced breath sounds

- Hyperresonant percussion

- Absent tactile fremitus (vibration intensity): detection of vibration with a hand placed over the thorax and the patient speaking

- Absent vocal resonance (sound intensity): transmission of sound when speaking with the stethoscope over the chest

Concerning features

Look out for patients with evidence of severe respiratory distress and/or haemodynamic instability (e.g. hypotension, marked tachycardia) because this indicates tension pneumothorax. See chapter on Tension pneumothorax below.

Diagnosis

If the patient presents with features of tension pneumothorax, imaging must not delay urgent decompression.

The diagnosis of a pneumothorax is made through imaging, typically with a chest radiograph. However, the use of imaging first depends on whether the patient is stable or unstable:

- Unstable: in a haemodynamically unstable patient, this likely represents tension pneumothorax and the priority is clinical assessment and urgent decompression.

- Stable: in a haemodynamically stable patient, there is time to request the appropriate imaging modality (e.g. x-ray or CT) before further intervention.

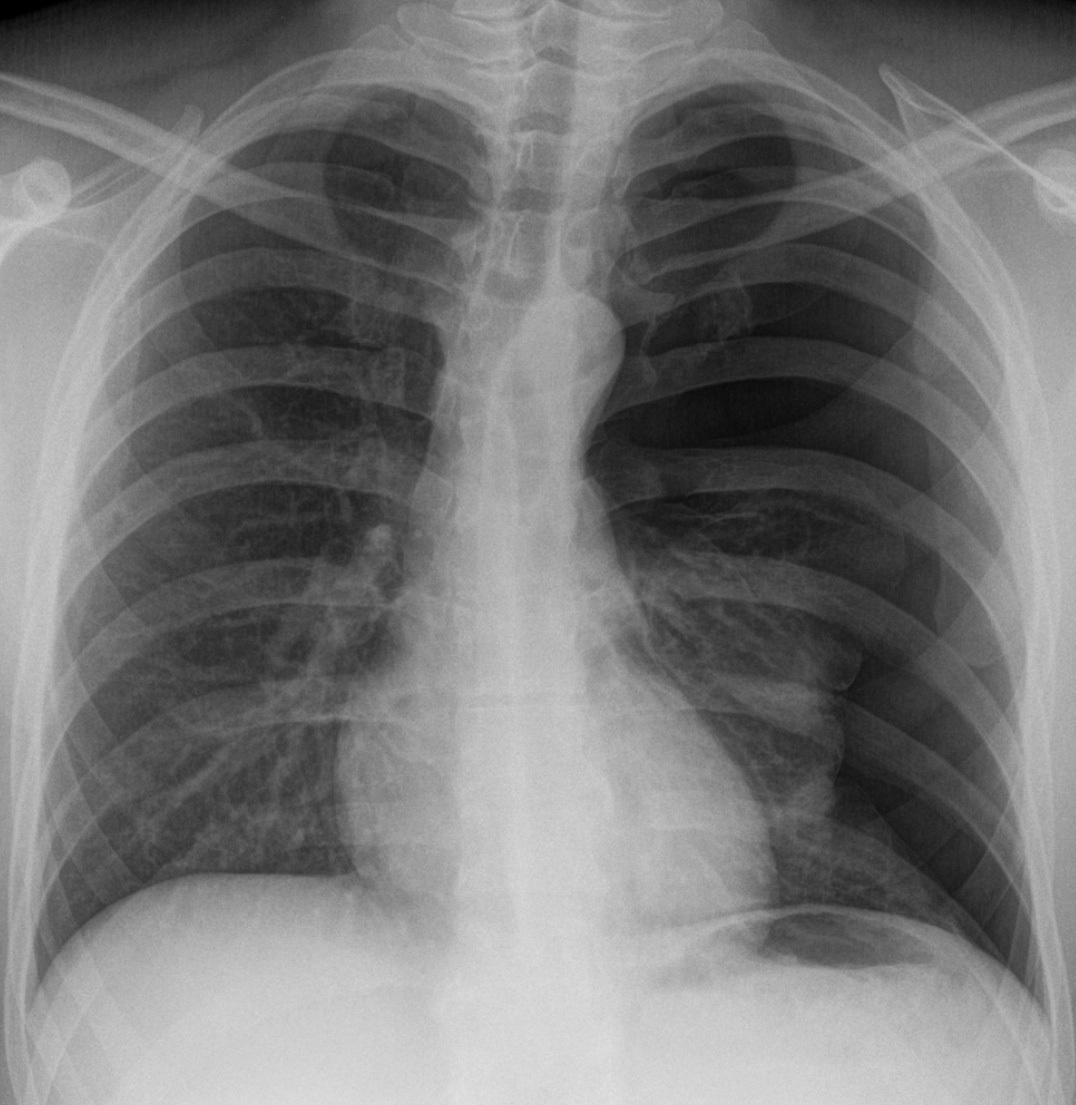

Chest radiograph

Erect chest x-ray is the standard first line imaging, allows size of pneumothorax to be estimated. A subtle pneumothorax may be missed and quantification of size may be inaccurate.

Of note supine radiographs are less sensitive, CT or USS should be considered in patients unable have an erect film.

Be aware, severe bullous lung may be mistaken as a pneumothorax. Placing a chest drain into a bullae has disastrous consequences. If diagnostic uncertainty exists review with a senior physician and consider a CT chest.

AP chest radiograph demonstrating a spontaneous left-sided pneumothorax

Image courtesy of Hellerhoff

USS

It may be of use in trained hands, however is typically used in the trauma setting to complete a FAST scan. Therapeutically may be used to aid drain placement.

CT Chest

Increasingly used and can be considered the gold-standard. Identifies subtle pneumothoraces and allows accurate estimation of the size.

Essential in cases with diagnostic uncertainty. May be used by interventional radiologist to place chest drains in the presence of significant bullae or surgical emphysema.

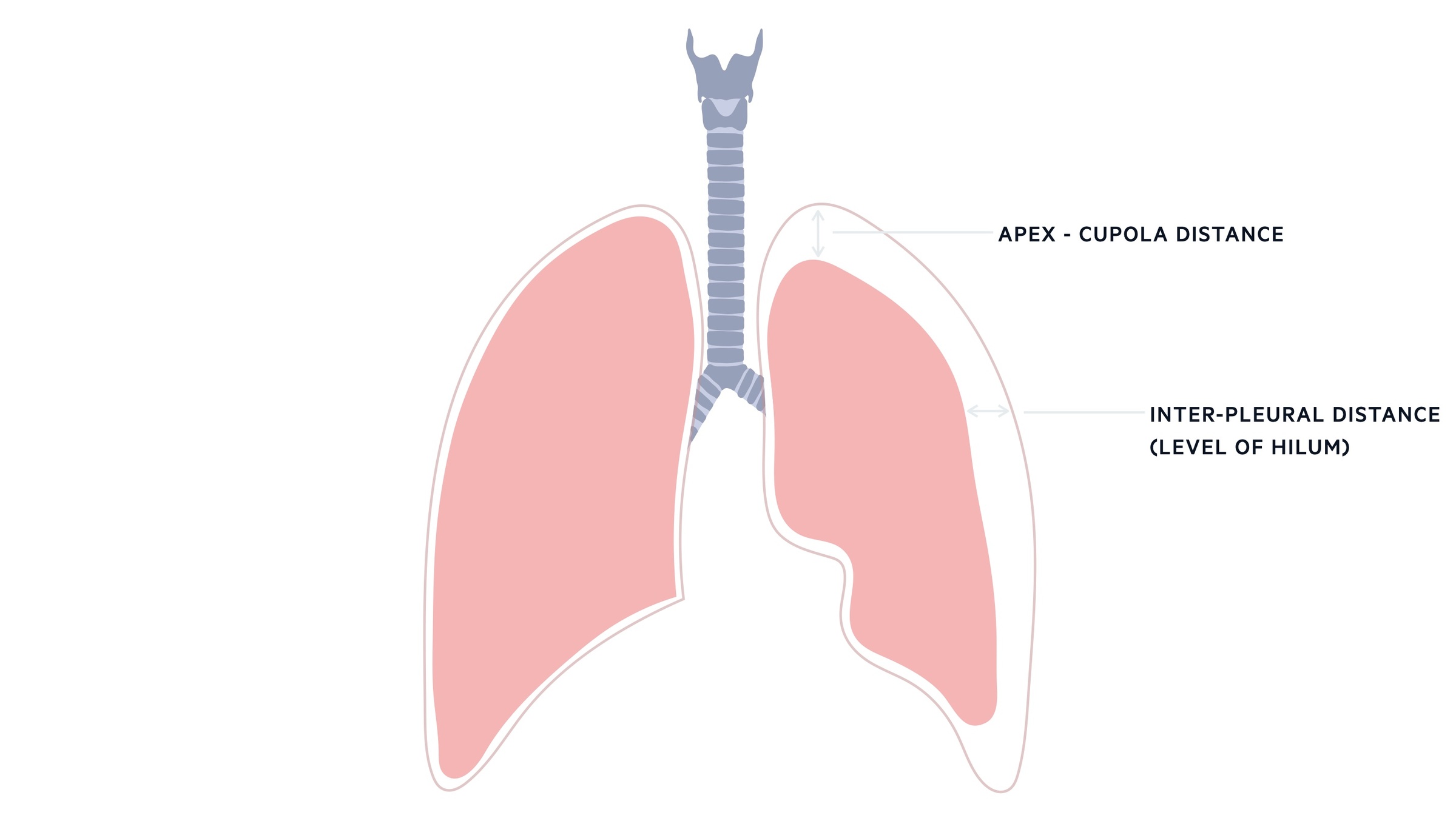

Size estimation

Size of a spontaneous pneumothorax helps to guide its management.

The size of a pneumothorax can be measured on conventional x-ray using two methods:

- Apex measurement

- Hilum measurement

The 2010 British Thoracic Society guidelines advise measurement at the level of the hilum. A cut-off of 2cm, between the chest wall and margin of the lung at this level, differentiates radiographically between ‘small’ and ‘large’ pneumothoraces.

CT scanning may be used to obtain truly accurate measurements. One important point to mention is that pneumothorax size does not always correlate well with the degree of symptoms and clinical compromise.

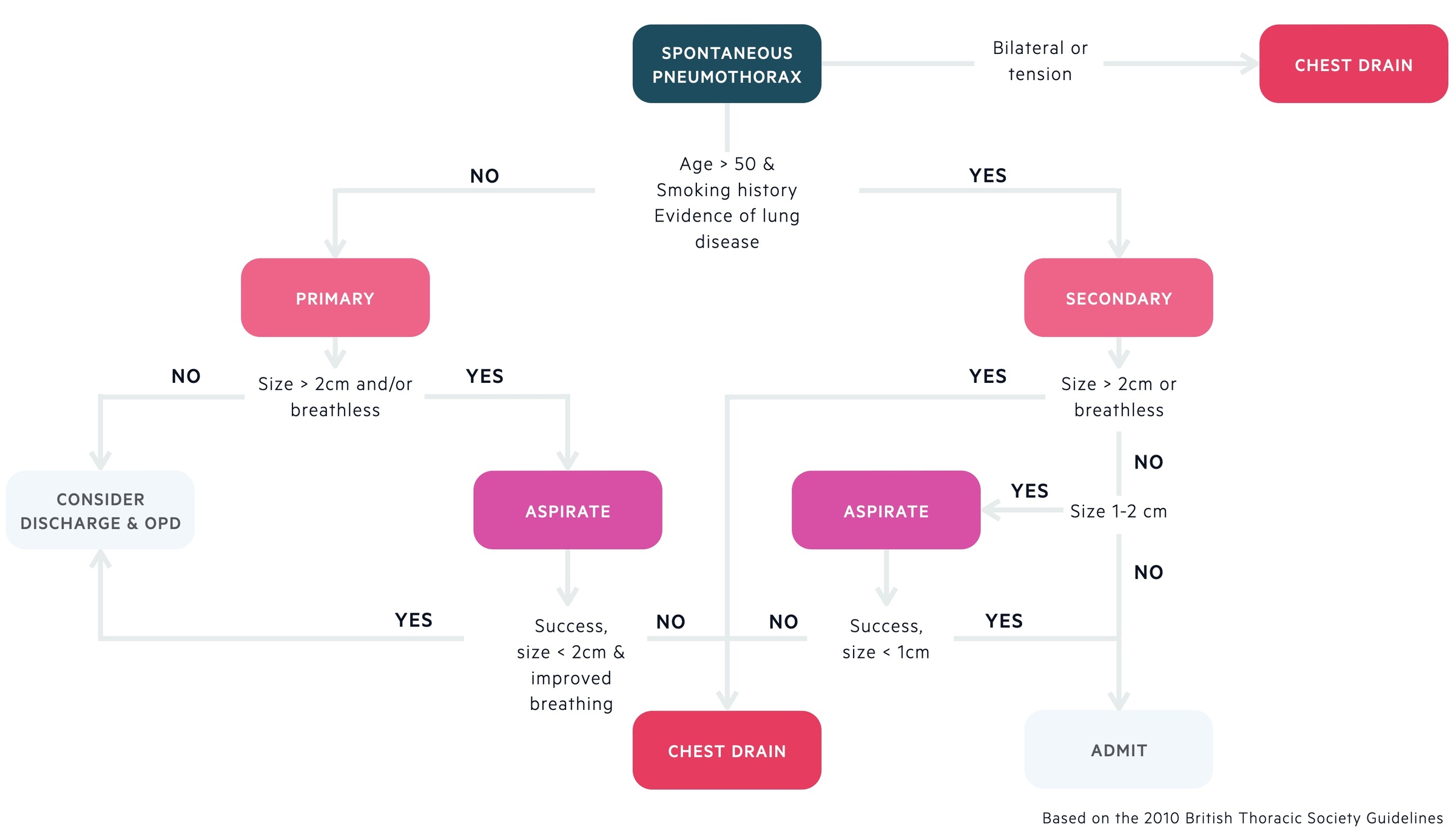

Management

Treatment should be guided by the patients symptoms and radiological findings.

Primary spontaneous pneumothorax

- Large (>2cm) or breathless:

- It is advised that people with large pneumothoraces or are breathless undergo active intervention. Needle aspiration (14-16G needle) is typically advised first as it has been shown to be effective and is associated with a decreased length of stay when compared to a chest drain. Stop after 2.5L has been aspirated.

- If needle aspiration fails a small bore (<14 F) Seldinger chest drain can be inserted. All patients with a chest drain must be admitted and referred to local specialists.

- Some patients with large pneumothoraces whom are asymptomatic may be managed conservatively. This should be decided with specialist input.

- Small (<2cm) and asymptomatic:

- Observation with outpatient follow-up is appropriate for small (<2cm) pneumothoraces with minimal symptoms.

- Patients should be advised to return if they develop breathlessness. Admit for observation if unable to comply with such advice.

All patients should be referred to respiratory specialists and have specialist follow-up. Many will advise routine supplemental oxygen.

Secondary spontaneous pneumothorax

- Large (>2cm) or breathless: Place a small bore (<14 F) Seldinger chest drain.

- Size 1-2cm: Needle aspiration (14-16G needle) is typically advised first as it has been shown to be effective and is associated with a decreased length of stay when compared to a chest drain. Stop after 2.5L has been aspirated.

- Size < 1cm: Admit and observe for at least 24h, consider supplemental oxygen.

Consider drain placement under CT guidance if technically challenging. All patients should be referred to respiratory specialists. If air leak is persistent beyond 48 hours discuss with thoracic surgery.

Referral to thoracic surgery

Patients with persistent air leak should be referred to thoracic surgeons for an opinion. It should however be noted that it may take 14 days for air leak from primary pneumothoraces to resolve with chest drain management.

Other reasons to refer to thoracic surgeons include:

- Ipsilateral recurrence

- Bilateral (synchronous) pneumothoraces

- Contralateral non-synchronous pneumothoraces

- Pregnancy

- At risk occupations (e.g. pilots)

Tension pneumothorax

Tension pneumothorax represents a medical emergency requiring prompt recognition and treatment.

Tension occurs when a ‘one way valve’ system allows air into the inter-pleural space but does not let it escape. This results in increasing pressures, which impair venous return to the heart, compromising cardiac output.

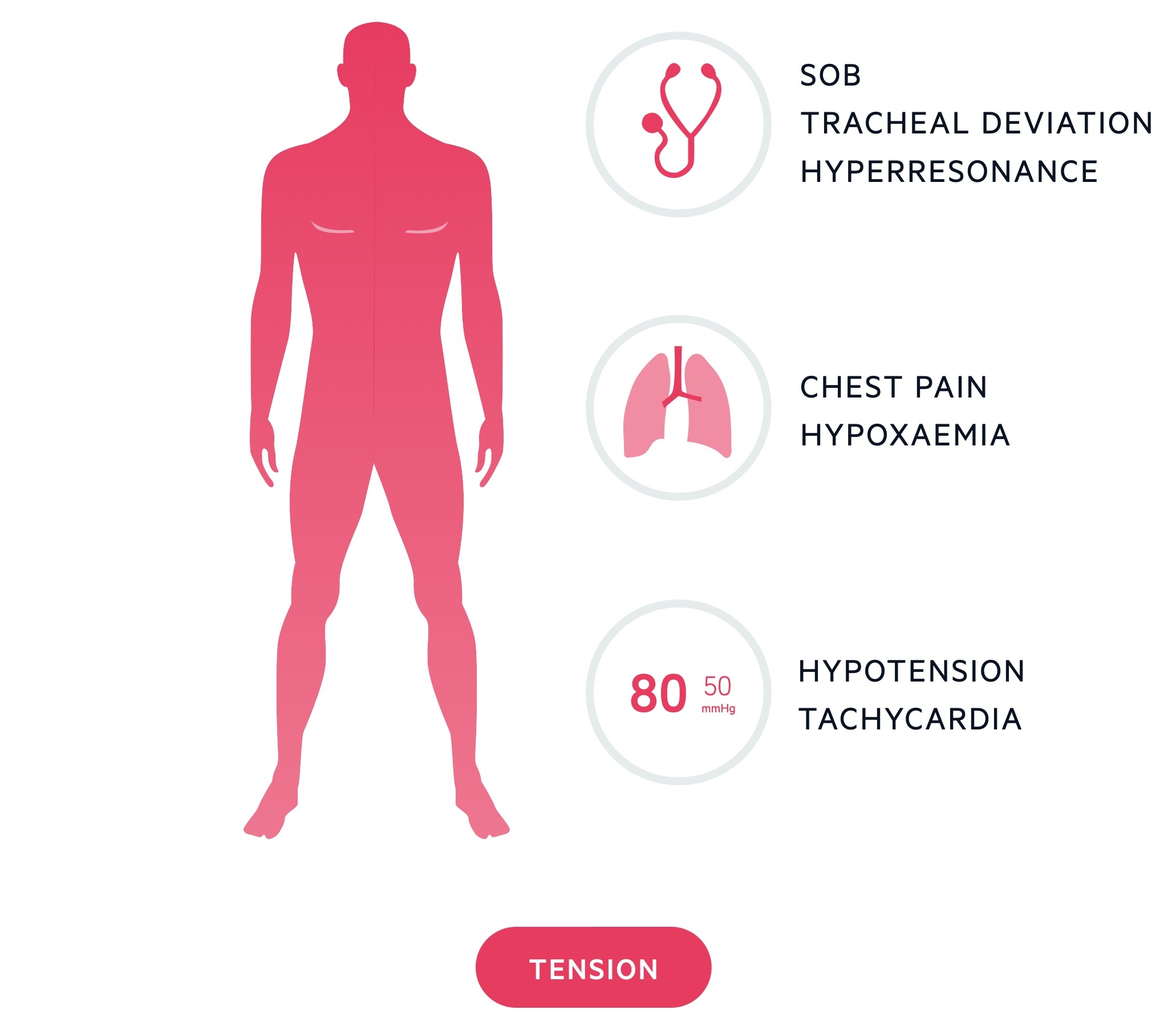

Clinical features

Patients with a tension pneumothorax will show signs of respiratory distress and shock (e.g hypotension, tachycardia). Once diagnosed, do not delay treatment. Remember, tension pneumothorax may present in a range of clinical settings including the inpatient population. Patients receiving non-invasive ventilation and mechanical ventilation are at risk. It may also occur due to blocked or malpositioned chest drains.

Management

If the diagnosis is made, administer high flow oxygen and carry out urgent needle decompression, imaging should not be awaited. Decompression can be achieved by placing a large-bore cannula in the 2nd intercostal space midclavicular line on the side of the pneumothorax. This cannula should be left in place until a formal chest drain is correctly placed.

Further advice

At discharge, clear advice to return if they develop breathlessness or chest pain should be given.

Patients should be booked respiratory follow-up at discharge. All should be followed up until full resolution. Smoking is associated with recurrence and cessation support should be offered.

Flights must be avoided until complete resolution. Most would advise at least two weeks after successful treatment and re-expansion.

Patients are advised to permanently avoid diving. Diving may be possible after successful surgical intervention with normal post-operative tests. This should be guided by respiratory specialist.