Overview

Sarcoidosis is a rare multisystem granulomatous disorder of unknown aetiology.

Sarcoidosis is considered a multi-system disorder that most commonly affects the lungs. The aetiology, though poorly understood, is thought to involve immune dysfunction and T-cell overactivity.

Sarcoidosis can have a wide range of clinical manifestations and is able to affect most organ systems within the body. Nonetheless, sarcoidosis most frequently affects the lungs causing a form of interstitial lung disease.

Epidemiology

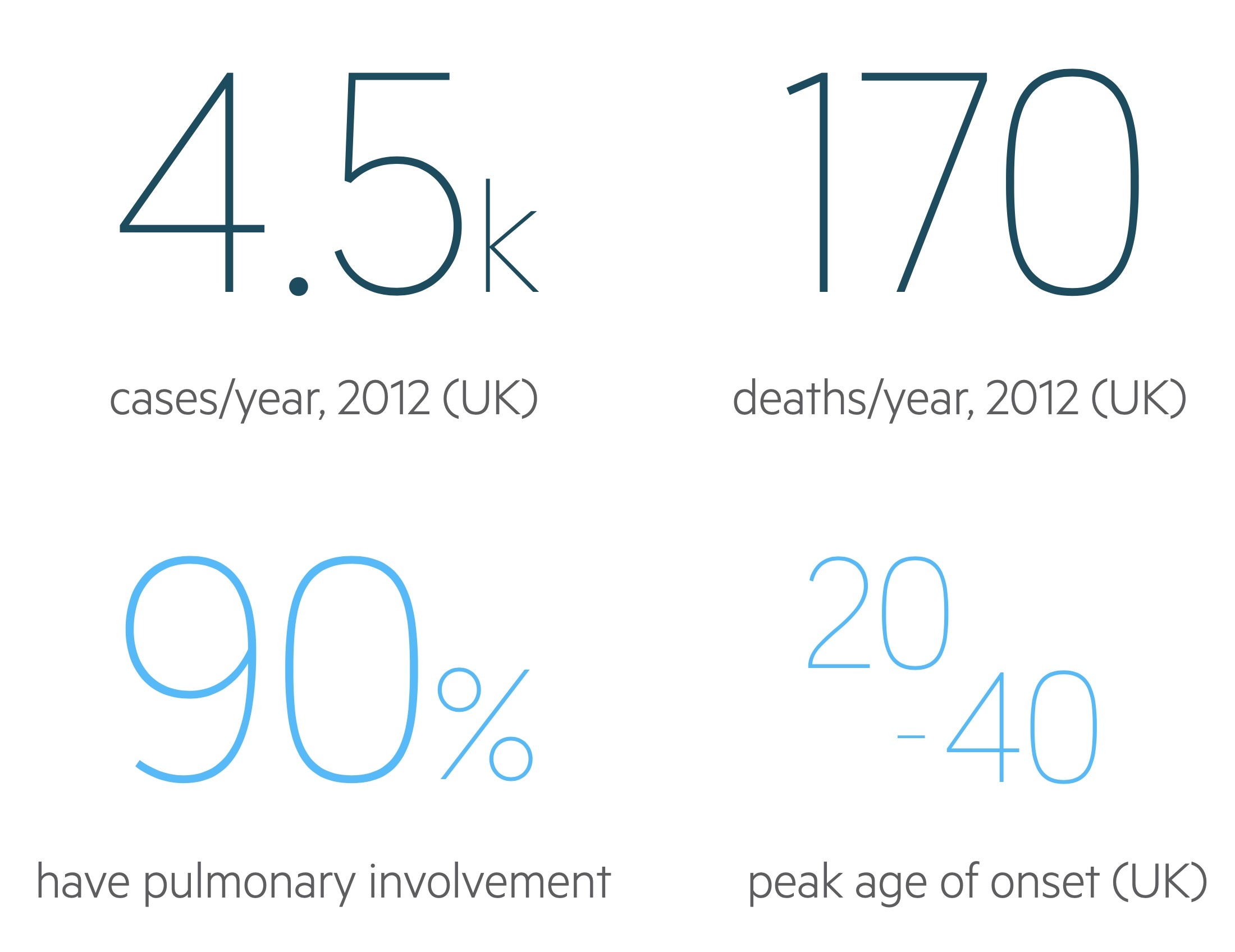

Sarcoidosis affects approximately 10-20 people per 100,000 in the UK.

There is a great deal of geographic variation in the prevalence and clinical manifestations of sarcoidosis. In Finland the prevalence is approximately 28.2/100,000 whilst in Japan it is far lower at 3.7/100,000.

In the US Black Americans are far more commonly affected than White Americans though this predisposition isn’t always reflected in other countries. Peak age of onset and clinical manifestations varies from country to country and study to study. In the UK onset tends to be between 20 – 40, though it can occur at any age. The condition is generally more common in women with a 2:1 female-to-male ratio.

Pulmonary sarcoidosis

The lungs are affected in 90% of patients, though signs and symptoms may be absent or subtle.

Sarcoidosis causes an overactive cellular immune response. Advanced pulmonary sarcoidosis involves the development of fibrosis causing thickening of the pulmonary interstitium. Bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy is the hallmark finding on chest radiograph.

The main symptom (if indeed symptoms are present) is progressive breathlessness.

If fibrosis develops a number of signs may be identified on examination:

- Fine inspiratory crackles

- Exertional desaturations

- Clubbing

Additionally pulmonary disease may lead to a number of complications:

- Pulmonary artery hypertension

- Cor pulmonale

Ocular sarcoidosis

The eyes are affected in around 30-60% of cases most commonly in the form of uveitis.

Sarcoidosis may lead to a number of ocular pathologies.

Uveitis

Uveitis is inflammation of the uvea, a structure composed of (from anterior to posterior) the iris, ciliary body and choroid.

- Anterior uveitis is the inflammation of the iris (iritis) and may involve part of the ciliary body (cyclitis). Pain, redness and photophobia are typical.

- Intermediate uveitis is the inflammation of parts of the ciliary body.

- Posterior uveitis is the inflammation of the choroid (choroiditis). It may involve retinal vasculitis. Symptoms include floaters and visual loss.

Panuveitis describes inflammation of the entire uveal structure.

Other ocular pathologies

- Keratoconjunctivitis sicca

- Adnexal granulomas

- Secondary glaucoma

Cutaneous sarcoidosis

Skin manifestations are seen in around 25% of patients with sarcoidosis

A number of rashes may be seen:

- Papular sarcoidosis: multiple papules develop, generally on the head and neck or areas of trauma.

- Erythema nodosum: a panniculitis (a condition with inflammation of subcutaneous adipose tissue) characterised by red, painful nodules.

- Lupus pernio: a violaceous, nodular rash distributed over the nose and cheeks. It is pathognomonic but rare.

Other manifestations

Sarcoidosis may manifest itself in many ways.

Hypercalcaemia is seen in around 15% of cases. This occurs due extra-renal synthesis of calcitriol causing 1-α hydroxylation of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and so increases levels of activated vitamin D. This leads to increased levels of calcium.

Renal disease may occur but is rarely clinically relevant. Significant renal disease sometimes occurs secondary to hypercalcaemia which may cause nephrocalcinosis. Granuloma formation can lead to interstitial nephritis but this is rarely of significance.

CNS disease is rare but may be severe. Arthralgia and bone cysts (particularly in the digits) and hepatosplenomegaly may be seen. Cardiac involvement is rare, it can present with arrhythmias, cardiomyopathy and heart failure.

Heerfordt’s syndrome, also termed uveoparotid fever, is a variant of sarcoidosis characterised by uveitis, parotid swelling, fever and facial nerve palsy.

Löfgren’s syndrome is an acute variant of sarcoidosis characterised by bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, erythema nodosum, arthralgia and fever.

Spirometry

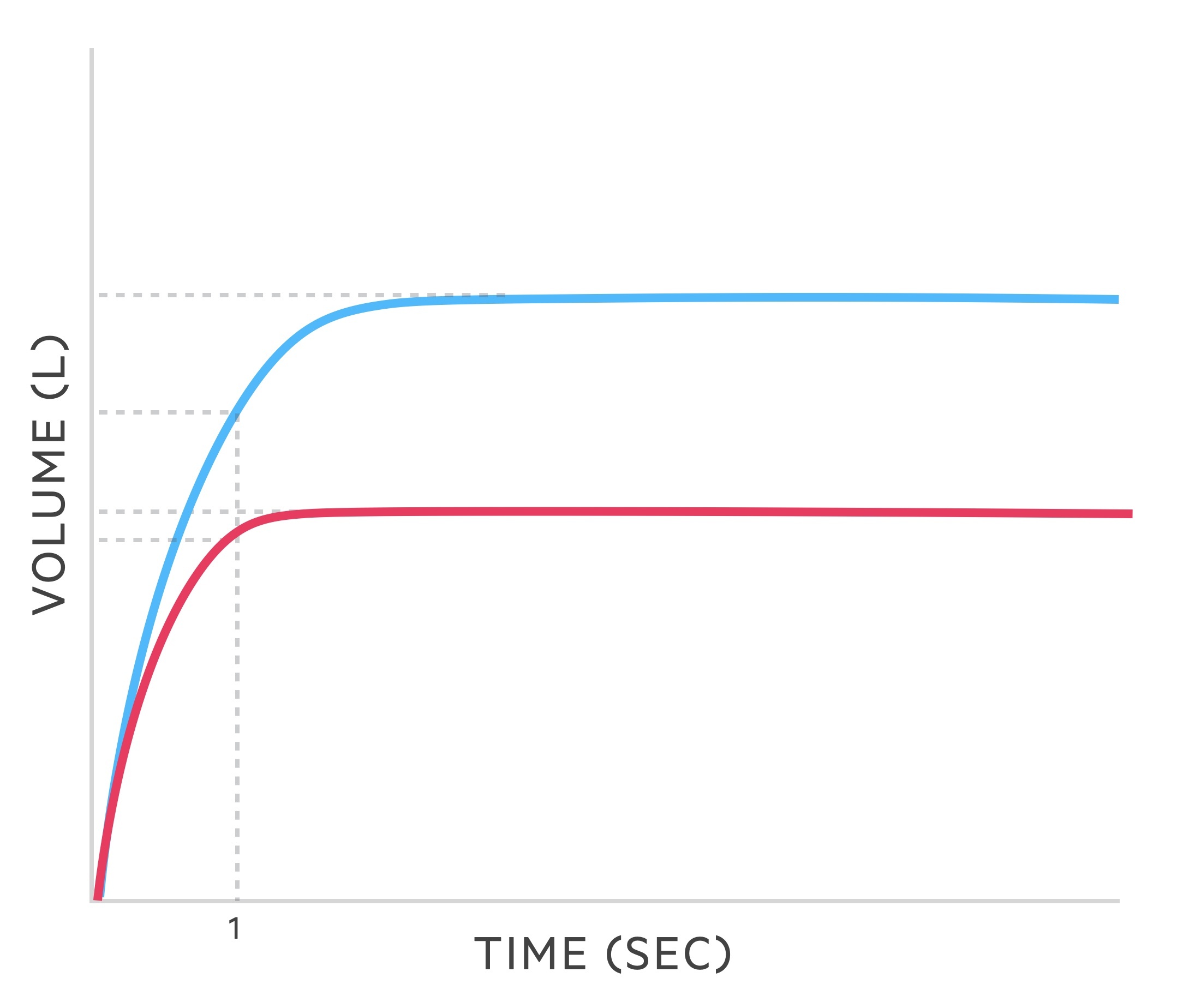

In cases of pulmonary sarcoidosis with pulmonary infiltrates and fibrosis a restrictive lung disease pattern is seen.

Spirometry measures the flow and volume of air during inhalation and exhalation.

- FVC: the forced (expiratory) vital capacity is a persons maximal expiration following full inspiration.

- FEV1: the forced expiratory volume in one second, i.e the volume of FVC expelled after one second.

Restrictive pattern

The following changes are seen in restrictive lung disease such as sarcoidosis:

- FVC: reduced

- FEV1: reduced

- FEV1/FVC: > 80%

Investigations

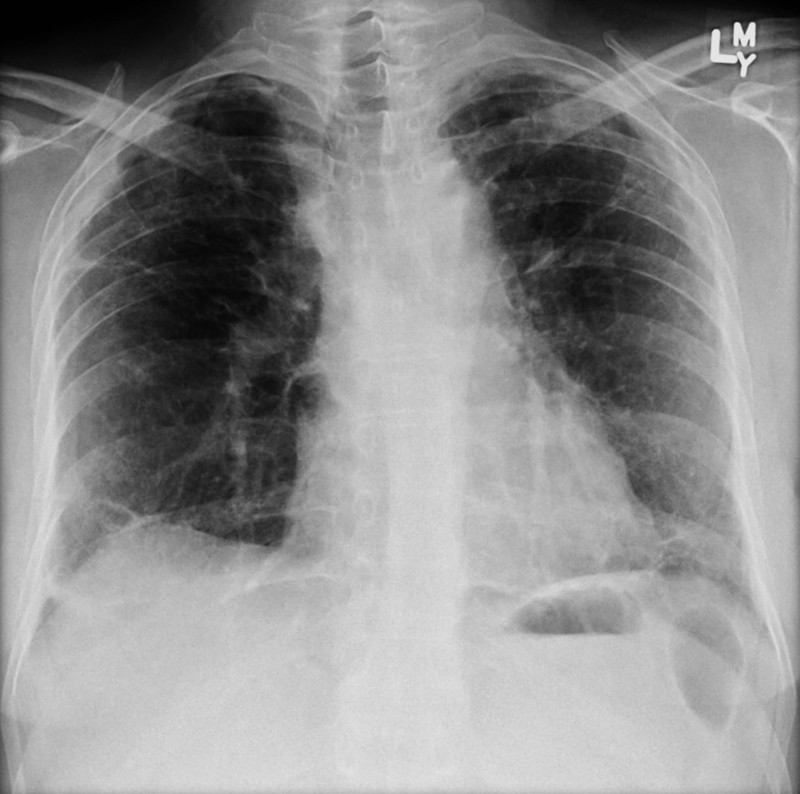

Bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy is a characteristic finding in sarcoidosis.

Investigations should be guided towards the site of suspected pathology. Sarcoidosis predominantly affects the lungs, which means imaging forms a crucial part of the investigations.

Bedside

- Observations

- Mantoux test: both TB and sarcoidosis cause cavitating lung lesions. May be difficult to distinguish.

Bloods

- Full blood count

- Renal function

- Liver function tests: sarcoidosis can cause liver disease

- ESR/CRP

- Bone profile:

- Hypercalcaemia is seen in around 15%.

- Serum ACE:

- Raised in around 70%, levels show a response to treatment. However, it is not accurate enough to be used diagnostically and has limited prognostic value.

Imaging

A CXR may reveal:

- Bilateral hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy

- Reticulonodular opacities

- Airspace opacities

- Pulmonary fibrosis

CXR findings may be used to stage disease – see the ‘Scadding staging’ chapter below. It should be noted no changes are seen in 20% of patients.

Features of sarcoidosis on CXR including mediastinal nodal enlargement

Image courtesy of Assoc Prof Frank Gaillard and Radiopaedia

Depending on disease progression high-resolution CT may demonstrate:

- Lymphadenopathy

- Diffuse nodularity

- Ground glass opacification

- Fibrosis (upper lobe predominance)

FDG PET may be used in select cases where there is ongoing diagnostic uncertainty, particularly where cardiac sarcoidosis is suspected.

Special

- Spirometry: shows a restrictive defect

- Tissue biopsy: need to confirm the diagnosis (see diagnosis section below)

- Lumbar puncture: if CNS disease suspected

Diagnosis

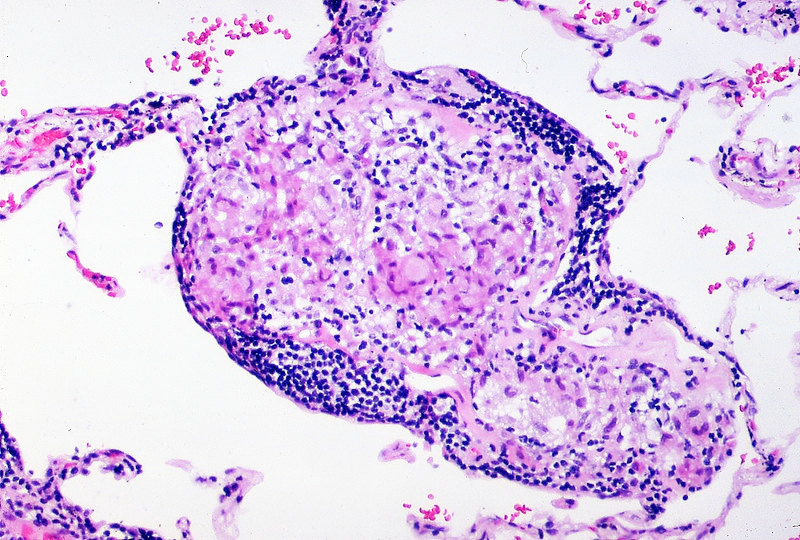

Tissue biopsy is needed to absolutely confirm a diagnosis of sarcoidosis, though it may not always be required.

Tissue biopsy is needed to confirm a diagnosis of sarcoidosis. This is of great importance as other conditions that can mimic radiographical appearances of sarcoidosis include other interstitial lung disease, malignancies and TB.

Clinical diagnosis may be made without the need for biopsy following other relevant investigation and discussion at specialist MDTs. The British Thoracic Society: Sarcoidosis Clinical Statement (2020) describe two scenarios where a clinical diagnosis can be made:

- Lofgren’s syndrome: there should be no suspicion of other diagnoses. Patients should follow close monitoring and follow-up.

- Long-standing pulmonary disease: with a classical initial presentation, with no suspicion of other diagnoses, and stable, typical, imaging findings following MDT discussion.

In those with suspected pulmonary sarcoidosis bronchoalveolar lavage ± transbronchial biopsy may be arranged. The classic histopathological finding in sarcoidosis is a noncaseating granuloma. These are collections of macrophages, epithelioid cells, t-lymphocytes (normally CD4 +ve) and giant cells that are noncaseating (or non-necrotising) – that is the centre has not undergone caseating necrosis. This is then surrounded by both T- and B- lymphocytes, mast cells and fibroblasts.

Brochoalveolar lavage can show features supportive of sarcoidosis including raised lymphocytes and a CD4/CD8 ratio > 4.

Noncaseating granuloma surrounded peripherally by a band of lymphocytes

Image courtesy of Yale Rosen

Scadding staging

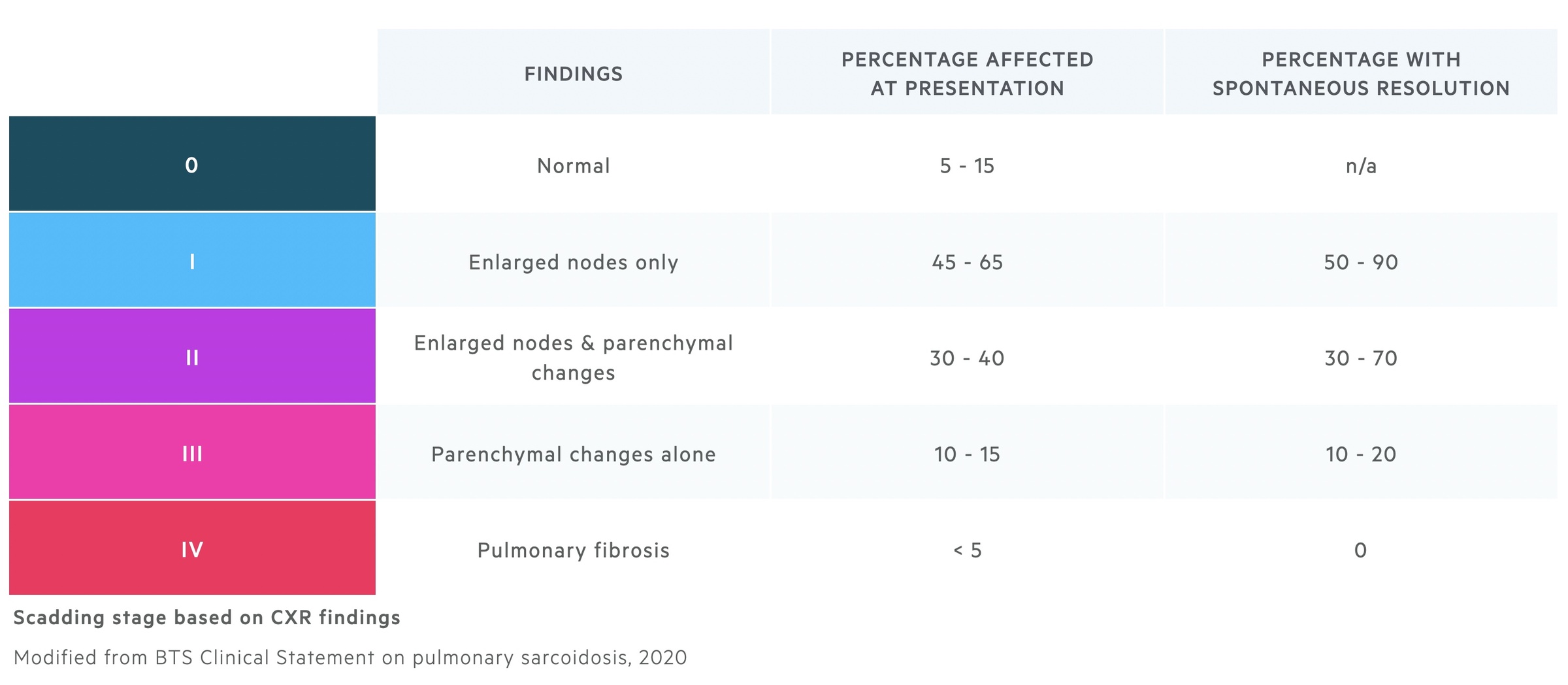

Scadding staging may be used to stage pulmonary sarcoidosis based upon chest radiograph findings.

The Scadding staging system was first published in the early 1960’s. It is based on chest radiograph findings and is used to predict the chance of spontaneous resolution. Though widely used it does have its limitations – it correlates relatively poorly with the severity of patients symptoms and does not predict well those who will need treatment.

Managing pulmonary disease

Many patients will not require active treatment for sarcoidosis.

Patients should be counselled on the condition, its prognosis and both the benefits and risks of treatment. It is known that disease will regress in a significant cohort of patients without treatment. Additionally, the treatments themselves carry their own risks.

As such the British Thoracic Society (BTS) state treatment should only be started if:

- Potential danger of a fatal outcome or permanent disability or

- Unacceptable loss of quality of life

As with all chronic diseases, patients should be offered support and counselling. The optimisation of lifestyle factors may involve smoking cessation, weight loss and dietary advice.

Pharmacological treatment

The decision to initiate drug therapy is influenced by the factors discussed above (risk of fatal outcome/disability or loss of quality of life) and the feelings of the patient.

When indicated it involves the administration of immunosuppressive medications. BTS divides these into three groups:

Steroids

Prednisolone has been the mainstay of management for many years. Typically initial treatment consists of:

- High-dose induction: typically 20 – 40mg each day for 4 – 6 weeks

- Dose tapering: the initial dose is gradually reduced (e.g. 5mg every two weeks)

- Maintenance dose: typically 5 – 10mg each day

Patients should be monitored for steroid-related side-effects. Bone protection should be strongly considered in patients on prolonged courses.

Withdrawal of therapy may be trialled after the threat to organ/life has resolved. In those who relapse treatment is re-initiated and further attempts are made at withdrawal at 6-12 month intervals.

Classical immunosuppressants

These are generally considered to be second-line agents. Options include methotrexate, azathioprine, leflunomide and mycophenolate They may be used in patients:

- With significant side-effects from steroids

- Co-morbidities putting patients at greater risk of steroid-related side effects

- Progressive pulmonary disease / unacceptable ongoing symptoms

- Inability to taper steroids to an acceptable maintenance dose

- Patient aversion to steroid therapy – may be used as initial therapy

All second-line therapies have significant side effect profiles. Baseline full blood count, renal function, liver function and viral hepatitis screen should be arranged. Contraindications to treatment include an eGFR < 30, ALT greater than two times the upper limit of the normal range (unless cause is sarcoidosis) or chronic hepatitis B/C.

Methotrexate, an antimetabolite, is generally the first choice of the second-line agents. Doses are given weekly alongside folic acid supplementation to reduce the risk of myelosuppression. Side effects include the aforementioned myelosuppression, rashes, alopecia and pneumonitis.

Biologics

Biologic agents are considered third-line therapy. They are indicated after treatment failure and use is directed by specialist tertiary centres.

Anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF) agents (e.g. infliximab) reduce inflammation by blocking the inflammatory cytokine TNF. They are known to trigger the reactivation of latent TB and as such patients must be screened and treated for latent TB.

Lung transplantation

Lung transplantation is a significant procedure that may be indicated in those with:

- Advanced pulmonary fibrosis

- Pulmonary hypertension

Bilateral transplant appears to have better outcomes than unilateral ones. Clinically significant recurrent disease is rare.

Prognosis

It is estimated there is a reduction in life expectancy in 6-8% of those with sarcoidosis.

Many patients with sarcoidosis will experience spontaneous regression and resolution of the disease. In those with pulmonary disease the chance of this can be predicted with the scadding staging (see above). The disease is known to be more severe in certain races, in black Americans mortality rates of 10% have been seen.

Pulmonary disease (including pulmonary fibrosis and pulmonary hypertension) is the predominant cause of sarcoidosis related death, implicated in around 70% of cases. Cardiac disease accounts for much of the remaining deaths.