Overview

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is an autosomal recessive multi-system disease predominantly characterised by respiratory features.

It is caused by mutations to the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene found on chromosome 7. This encodes a chloride channel and abnormalities have wide-ranging effects.

Since the introduction of newborn screening for CF in 2007, the vast majority of patients are diagnosed in the first two months of life. Others are diagnosed following characteristic presentations (e.g. failure to thrive, recurrent chest infections, steatorrhea)

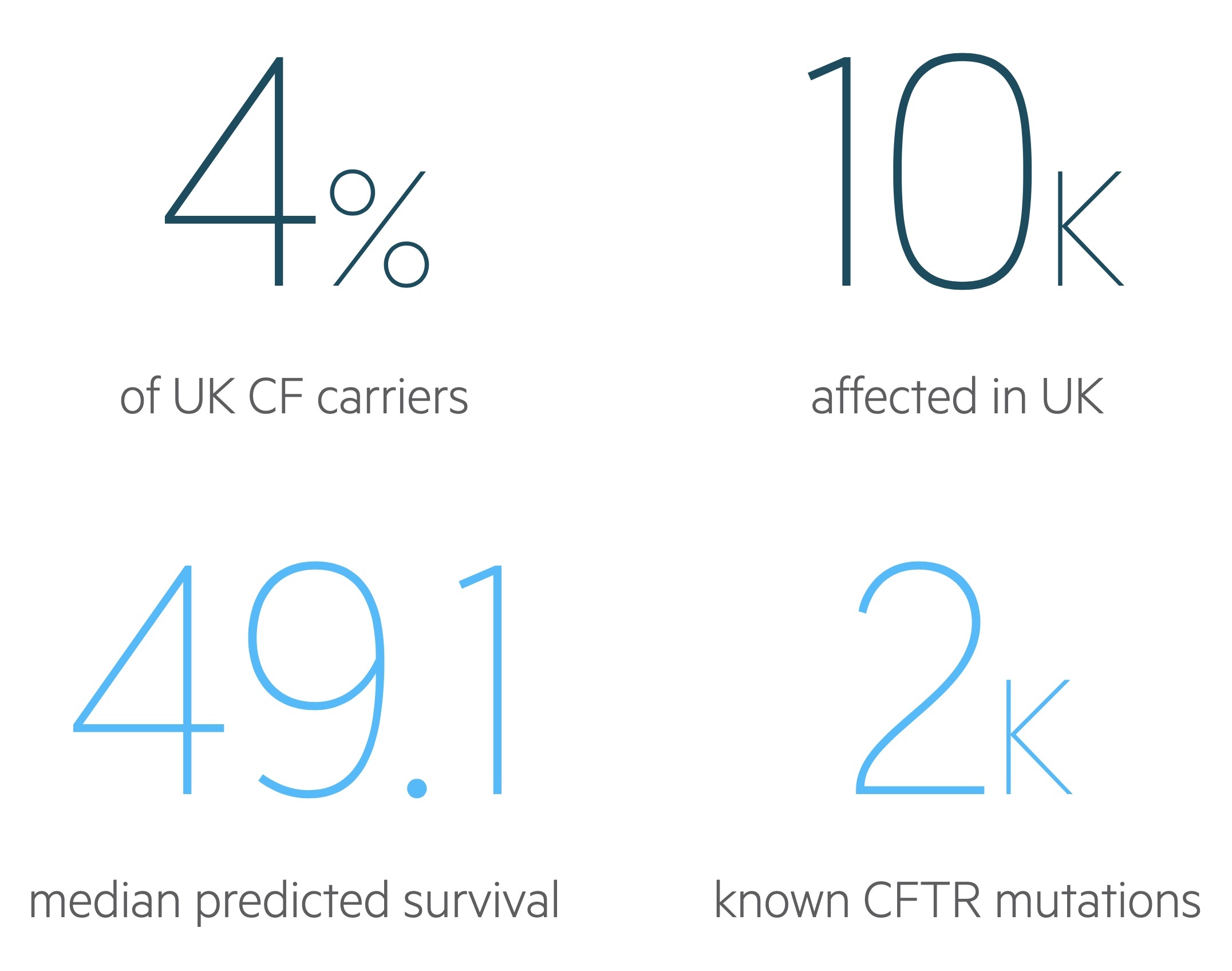

As treatment improves, we are seeing significant improvements in life-expectancy, based on data from the 2019 CF Registry Report the median predicted survival age is 49.1 years for individuals born in the UK today with CF.

Epidemiology

In 2019 there were an estimated 10,655 individuals affected by CF in the UK.

It is estimated 1 in 25 people in the UK are carriers of CF whilst 1 in 2,500 newborns have CF. In 2019 there were 193 newly diagnosed patients in the UK.

The disease is most common in those of white ethnicity. In the UK 93.3% of those affected were white, 2.8% asian, 1.1% mixed race and 0.2% black (remainder other/unknown).

Genetics

Mutations to the CFTR gene on the long-arm of chromosome 7 lead to CF.

The CFTR gene encodes for an epithelial chloride channel regulated by cyclic AMP. There are over 2000 identified mutations to CFTR leading to abnormal channels. Most of these are very rare with less than 10 mutations having a frequency greater than 1%. The variety of mutations explains the range of different phenotypic presentations seen in CF.

The most commonly identified mutation is delta-F508 (DF508) – a deletion of three DNA bases encoding for the amino-acid phenylalanine. A single copy of this mutation is found in up to 90% of patients, with around 50% homozygous though there is significant variations in different ethnic populations.

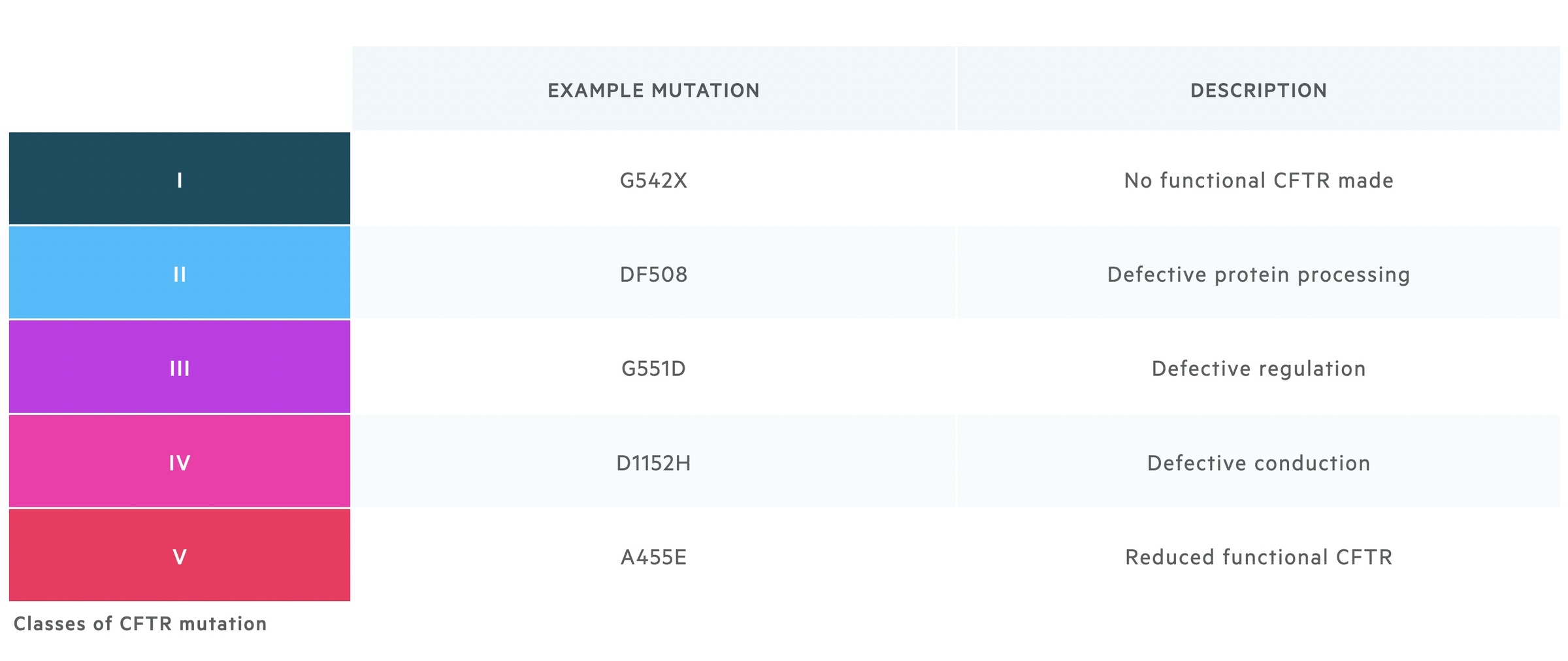

Mutations affect the CFTR gene in a variety of ways. They may result in no functional CFTR being produced, abnormal intra-cellular processing of key proteins, abnormal regulation of the channel, abnormal conduction of chloride through the channel or a reduction in functional CFTR reaching the cell membrane. There are a number of ways to classify mutations to CFTR, each with slight variations, one of which is shown below.

Pathogenesis

CF results in dehydration of airway surface fluid resulting in mucociliary dysfunction.

At birth patients have seemingly normal lungs and respiratory function. However, as they grow older the disease is characterised by chronic and recurrent pulmonary infection.

In the lungs CFTR channels are found on the apical surface of epithelial cells. Defects in normal ion transport leads to dehydration and depletion of airway surface liquid – which is key to the normal function of cilia. The resultant mucociliary dysfunction causes reduced mucus clearance, airway obstruction and a predisposition to infection. Recurrent infection leads to chronic bronchitis, damage to the bronchi and eventual bronchiectasis – the permanent dilation of bronchi secondary to damage to the elastic and muscular components of the bronchial wall.

Similar issues are seen in other organs with impaired biliary and pancreatic drainage due to viscous secretions resulting in impaired digestion and malabsorption. Pancreatic insufficiency is common in patients with CF and patients can suffer with recurrent acute pancreatitis or chronic pancreatitis. Damage to pancreatic islets may result in CF-related diabetes. Liver impairment is common and ranges from transient derangement of LFTs through to portal hypertension and cirrhosis.

Presentation

In the UK CF is universally screened for as part of newborn heel prick test.

The heel prick blood test, conducted at day 5 after birth, is used to diagnose nine conditions – one of which is CF. The diagnosis may be made prior to birth based on suggestive USS findings and confirmed with chorionic villus sampling / amniocentesis. Non-invasive techniques of prenatal diagnosis are being developed but are not widely available. CF may be suspected in newborns with meconium ileus (affects around 20%) and infants/children with failure to thrive, fatty stools or recurrent chest infections.

Presentation in adulthood is now considerably less common in the western world. They can present with respiratory symptoms whilst diabetes and infertility may be seen. Atypical presentation is more common and rarer mutations may be responsible for disease.

Clinical manifestations

Respiratory disease is the most common manifestation of CF and the most common cause of premature death.

Respiratory disease

Respiratory disease dominates the clinical features in most patients with CF. It is characterised by a productive cough and recurrent chest infections.

In childhood Staphylococcus aureus and Haemophilus influenza are commonly isolated. In older age groups colonisation with Pseudomonas aeruginosa becomes increasingly common, with chronic infection affecting around 40% of those over the age of 16 in the UK.

Recurrent infections result in bronchiectasis secondary to damage to the bronchial walls. This further compounds the pre-existing respiratory disease. The airways are dilated, weak and inflamed further reducing mucociliary clearance. A persistent, daily, productive cough results. As disease worsens progressive respiratory failure develops. Complications include cor pulmonale, haemoptysis and pneumothorax.

Pancreatic disease

Pancreatic involvement is common for patients with CF. The extent to which they are affected appears to depend on the underlying CFTR mutation.

Thick secretions block the outflow of exocrine digestive enzymes leading to insufficiency with fatty stools and malabsorption. In those with more severe pancreatic disease, autolysis destroys the pancreatic islets leading to CF-related diabetes.

Other patients are affected by recurrent acute pancreatitis and eventual chronic pancreatitis.

Gastrointestinal disease

CF is the most common cause of meconium ileus in term infants. Constipation is common at all ages but must be differentiated from distal intestinal obstruction syndrome (DIOS). DIOS is caused by obstruction of the ileocaecum by thickened gastric contents.

Malignancies

Patients with CF are at increased risk of gastrointestinal malignancies – including the large and small bowel, pancreas and biliary tract. Those with cirrhosis are at risk of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is now commonly made after a positive heel prick test (newborn screen) followed by confirmatory testing.

There are a number of tests that can be used to diagnose CF:

- Immuno-reactive trypsin test: the test used at newborn screening, a positive test is indicative but further confirmation testing is needed.

- Sweat test: can be used in children of any age. Sweat chloride > 60mmol/L is considered positive for CF. 30-59mmol/L is inconclusive (genetic testing indicated) and < 30mmol/L is considered negative.

- Genetic testing: common mutations are screened for, where not found sequencing of the entire CFTR gene may be completed.

NICE guideline 78: Cystic fibrosis: diagnosis and management (2017) advise the diagnosis of CF may be made in the following situations:

- Positive test results in people with no symptoms, for example infant screening (blood spot immuno-reactive trypsin test) followed by sweat and gene tests for confirmation or

- Clinical manifestations, supported by sweat or gene test results for confirmation or

- Clinical manifestations alone, in the rare case of people with symptoms who have normal sweat or gene test results.

NICE generally advise the sweat test is used children and infants whilst genetic testing is used in adult patients.

Managing pulmonary disease

Management of pulmonary CF involves encouraging clearance of secretions and treating/preventing infections.

The management of CF should place the patients (when old enough) at the centre of care. This is directed by CF centres with specialist paediatricians / adult physicians, nurses, physiotherapists, dieticians, pharmacists and clinical psychologists. Despite new and optimal therapies respiratory failure is the cause of premature death in the majority of patients with CF.

Patients with lung involvement need regular assessment of their disease that involves review of symptoms, examination, medication review, height & weight, imaging, functional testing and cultures of respiratory secretions. The time between reviews is based upon age and severity of disease. Non-medical interventions like regular exercise – tailored to an individuals abilities – help improve lung function and overall fitness.

The management of CF is an enormously complex area. However below we have summarised a few key aspects of care based on NICE guidance 78.

Airway clearance techniques

Patients and their parents/carers should be taught airway clearance techniques. The aim is to aid and improve the clearance of airway secretions to reduce the incidence of chest infections. These combined with mucoactive agents form part of a daily routine for many patients.

Mucoactive agents

These may be offered to those with evidence of lung disease to aid in the clearance of secretions from the airways. There are a number of options available:

- rhDNase (dornase alfa; recombinant human deoxyribonuclease): advised as the first-line option by NICE. Given via a nebuliser it cleaves extracellular deoxyribonucleic acid and helps reduce viscosity and promote sputum clearance.

- Hypertonic sodium chloride: may be used alone or with rhDNase in those with inadequate response. Given via a nebuliser, it has osmotic action that hydrates airway secretions and promotes their clearance.

- Mannitol dry powder for inhalation: used in patients intolerant, ineligible or not responding to rhDNase and have rapidly declining lung function and where other osmotic agents are not appropriate. Inhaled via a handheld device, it has osmotic action causing water to enter the airways, hydrating secretions and making clearance easier.

Pulmonary infection

Staphylococcus aureus

Oral flucloxacillin can be offered as prophylaxis to S.aureus infection for children up to the age of 3 – and may be continued to the age of 6. Those with positive respiratory cultures require treatment for an acute infection based on the given clinical context.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Patients with a new infection are treated with eradication therapy with oral/IV antibiotics and inhaled antibiotics. If the patient is clinically unwell IV antibiotics and inhaled antibiotics are used for eradication. Following initial treatment an extended course of oral and inhaled therapy is offered.

NICE advise that where eradication fails, sustained treatment with an inhaled antibiotic – for example with nebulised colistimethate sodium can be offered. In patients with chronic infection various combinations of inhaled, oral and IV therapies may be needed.

Other infections

Patients with CF are susceptible to a whole host of infections. NICE guidelines specifically cover (in addition to the above) burkholderia cepacia complex, haemophilus influenzae, non-tuberculous mycobacteria and aspergillus fumigatus complex.

For more information see NICE guidance 78.

Lung transplantation

In patients with progressive respiratory failure, lung transplantation is considered. In the vast majority this involves transplanting both lungs – Bilateral Sequential Lung Transplant – to avoid leaving a source of infected secretions. It is a major operation that is not without risks and requires life-long immunosuppression – medications which have many serious side-effects. It also does not address extra-pulmonary manifestations of CF.

Managing extrapulmonary disease

CF is a multi-system disease, though the pattern of involvement varies person to person.

Patients may require input from a number of specialist as detailed in the above chapter. Attention must be paid to each persons individual well-being and mental health with support offered where needed.

Nutrition & pancreatic insufficiency

Nutritional assessment forms a key part of the management of CF. Review should be offered with a specialist dietician giving individualised dietary advice and nutritional plans.

Where there is weight loss or inadequate weight gain, NICE advise increasing portion size and eating high-energy foods in the first instance. Nutritional supplements may be considered where this is unsuccessful. Ongoing deficit may need enteral feeding or a trial of an oral appetite stimulant.

Pancreatic insufficiency is common resulting in malabsorption and steatorrhoea. Patients with CF should be tested for this (e.g. with faecal elastase) – and if normal testing repeated as and when symptoms arise. In patients with insufficiency, oral pancreatic enzyme replacement (e.g. CREON) should be offered.

Liver disease

Patients should be screened regularly (at yearly annual review) for liver disease through history, examination and LFTs. Where abnormality is suspected a liver USS should be arranged.

Ursodeoxycholic acid may be given to those with abnormal liver function with the aim to improve bilary flow. It should be remembered that abnormal liver function tests may result from disease unrelated to CF or from medication side effects.

Around 40% of patients may develop CF related liver disease. A proportion will develop progressive, worsening disease with eventual portal hypertension and/or cirrhosis. Transplantation may be indicated in those with liver failure which may be completed alone or as a liver-lung or liver-pancreas transplant.

CF-related diabetes

CF often results in diabetes through damage to the pancreatic islets. It should be screened for annually from the age of 10 and at any times where symptoms are suggestive or the clinical situation demands. NICE recommend the diagnosis can be made with one of the following investigations:

- Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM)

- Serial glucose testing over several days

- Oral glucose tolerance testing (OGTT) – if OGTT is abnormal perform CGM or serial glucose testing over several days to confirm the diagnosis

When diagnosed patients need appropriate education as with all new diagnoses of diabetes. Treatment is with insulin.

Novel therapies

Several new therapies for the management of cystic fibosis known as CFTR modulators have been approved for use in the UK.

CFTR modulators and modulator therapies work by targeting the underlying mechanism in cystic fibrosis. Currently, four drugs are available in the UK that includes Kalydaco, Orkambi, Symkevi, and Kaftrio.

The choice of drug depends on the underlying cystic fibrosis mutation. For example, Kaftrio is a combination of three drugs (tezacaftor, ivacaftor and elexacaftor) that is used in patients with at least one F508del mutation. Tezacaftor and elexacftor bind to the CFTR receptor and increase the amount of CFTR delivered to the cell surface. Ivacaftor then helps facilitate channel opening. Collectively, these drugs increase CFTR activity.

The exact indications, prescribing, monitoring and efficacy of these novel therapies is beyond the scope of these notes.

Prognosis

The median predicted survival age in the UK is 49.1 years old for newborns with CF.

This is the figure from the 2019 Cystic Fibrosis Registry Report and is an estimate for patients born today with CF. It should be noted survival is predicted to be almost 6 years longer in men than in women (51.6 vs 45.7).

In 2019 itself, in the UK, an estimated 114 with CF died with a median age of death of 31. Between 2017-2019, the most common cause of death in the UK was respiratory / cardiorespiratory disease (70%) followed by transplant complications (9.4%), ‘other’ (6.5%) and cancer (5.0%).