Introduction

Asthma is a common chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways.

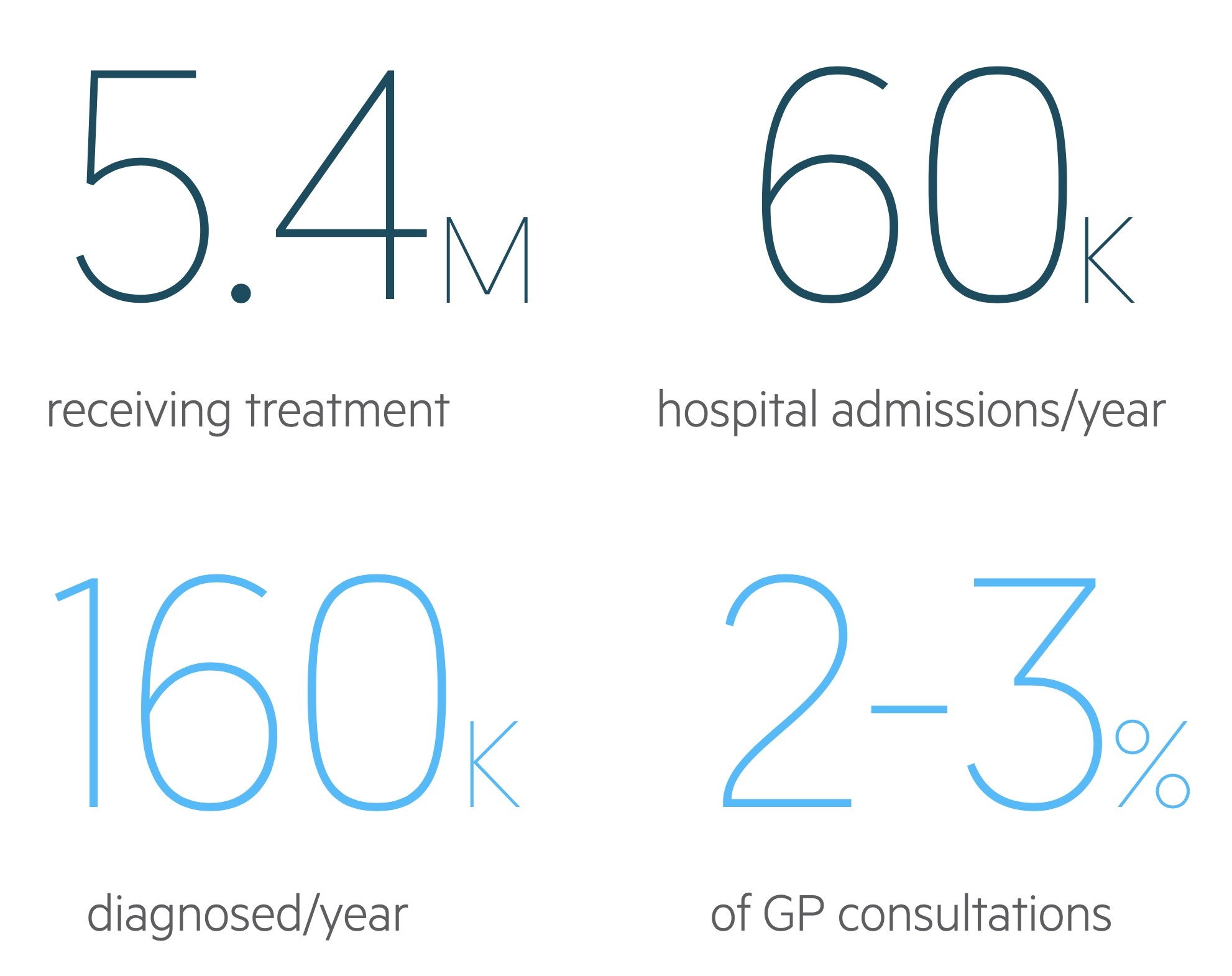

Approximately, 12% of the UK population have a diagnosis of asthma and 5.4 million are receiving treatment for the condition.

Clinically it presents with classical features including cough, wheeze, chest tightness, and shortness of breath. It can present acutely as an ‘exacerbation of asthma’, which may be life-threatening. It is characterised by:

- Reversible airflow limitation

- Airway hyperresponsiveness

- Inflammation of the bronchi

Over the last decade, the approach to the diagnosis and management of asthma has been changing rapidly. There are currently two broad guidelines for the management of asthma (NICE and BTS/SIGN).

Aetiology

Asthma is an enormously complex condition that may present at any age.

Many factors can contribute to the development of asthma, understanding these is key to effective management.

Atopy

Atopy is a genetic predisposition to IgE-mediated allergen sensitivity. Atopic individuals are predisposed to the following three conditions:

- Allergic asthma

- Atopic dermatitis

- Allergic rhinitis

Hygiene hypothesis

The hygiene hypothesis was first developed from epidemiological data showing increased autoimmune and allergic disease in western countries.

It postulates that reduced exposure to infectious pathogens at a young age predisposes individuals to such diseases. In simple terms, this environment is thought to encourage Th2 predominant response – one that produces IgE.

Aspirin-induced asthma

A small subset of patients with asthma are affected by a sensitivity to aspirin. Ingestion is capable of triggering an attack. These patients exhibit Samter’s triad:

- Asthma

- Aspirin sensitivity

- Nasal polyps

Occupational asthma

Around 15% of cases of asthma in adults are related to occupational exposure. Asthma may be induced or exacerbated by such exposure. Hundreds of sensitisers have been identified. They may be categorised as:

- High molecular weight: compounds that trigger an IgE-dependent response. The effects are immediate or soon after exposure (e.g. flour, latex).

- Low molecular weight: compounds develop a complex immune response after repeated and long-term exposure (e.g. isocyanates, wood dusts).

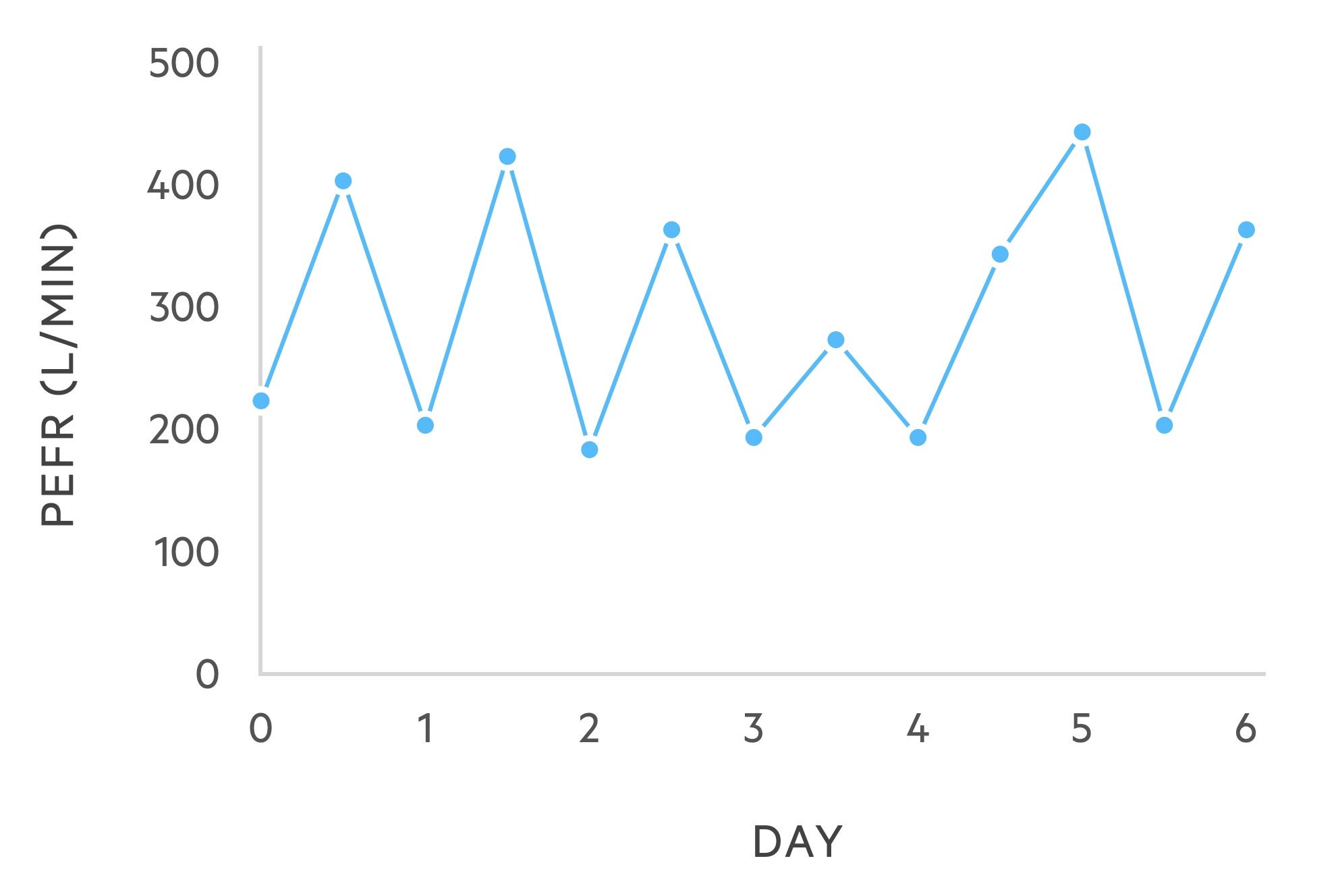

Peak expiratory flow diaries during periods of work and holiday are key to the diagnosis of occupational asthma.

Exercise-induced asthma

In this variant asthma is triggered by strenuous physical activity. The aetiology is complex but exposure to cold air and environmental pollutants contributes.

Pathophysiology

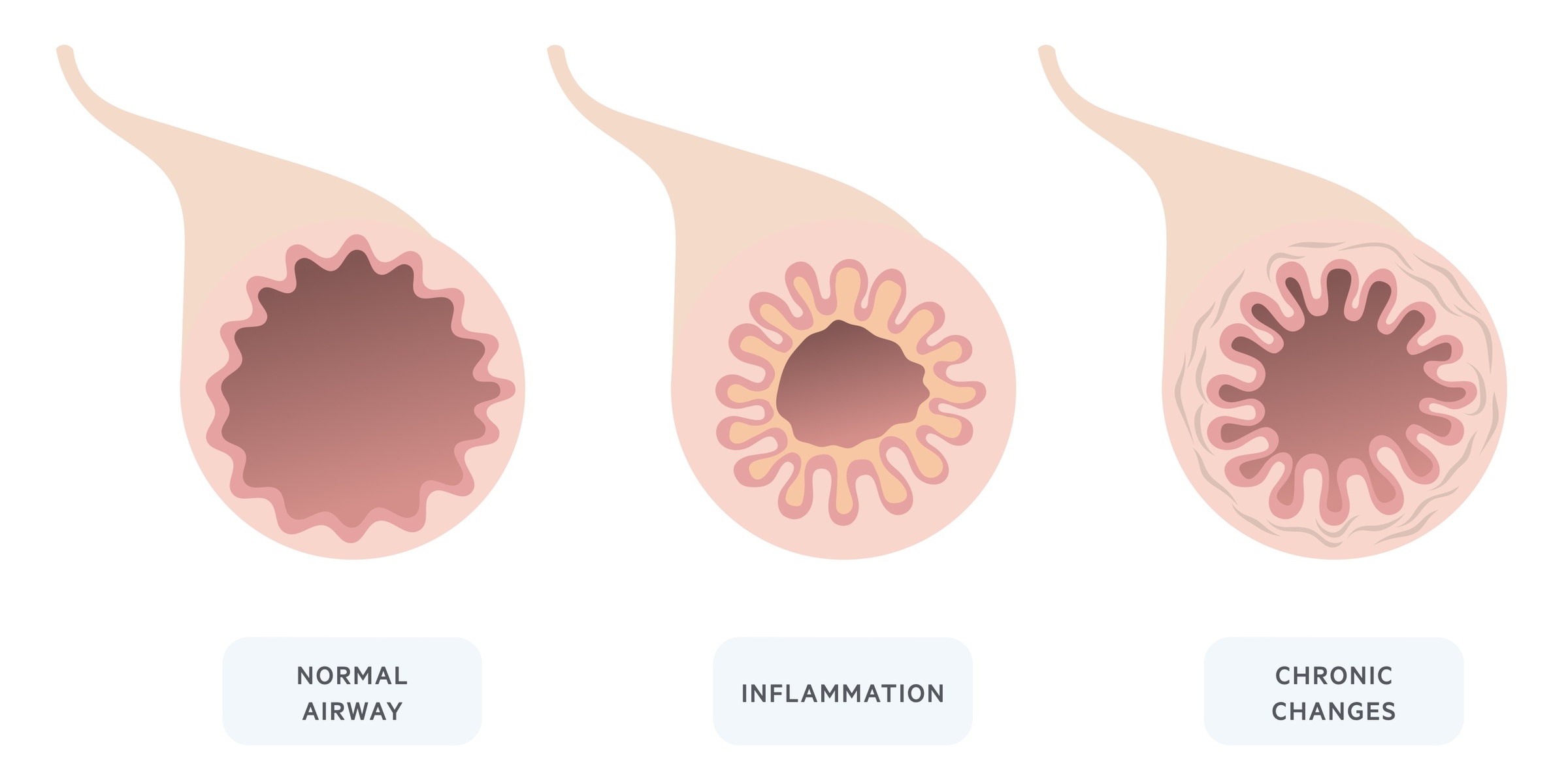

Asthma is the result of aberrant airway inflammation and bronchospasm, which contribute to an increase in airway resistance.

Early phase

Inhalation of allergens results in an immediate (type 1) hypersensitivity reaction in the airways.

Sensitisation occurs during the allergen exposure causing the release of IgE antibodies from plasma cells. IgE bind to high affinity receptors on mast cells.

Subsequent exposure to antigens cause mast cell degranulation and histamine release. These mediators cause smooth muscle contraction and bronchoconstriction whilst inflammation contributes to airway obstruction.

Late phase

The initial early phase reaction may be followed by a late response hours later. During the late phase, recruitment of a variety of inflammatory cells (e.g. polymorphonuclear cells, T-cells) occurs.

The late response is more complex than the early response involving multiple additional processes. Beta-agonists do not cause complete reversal of the late response.

Chronicity

In response to persistent chronic inflammation, the airways lay down fibrous tissue. Over time airway remodelling occurs and manifests as fixed airway obstruction – i.e. airway narrowing that is irreversible.

Clinical features

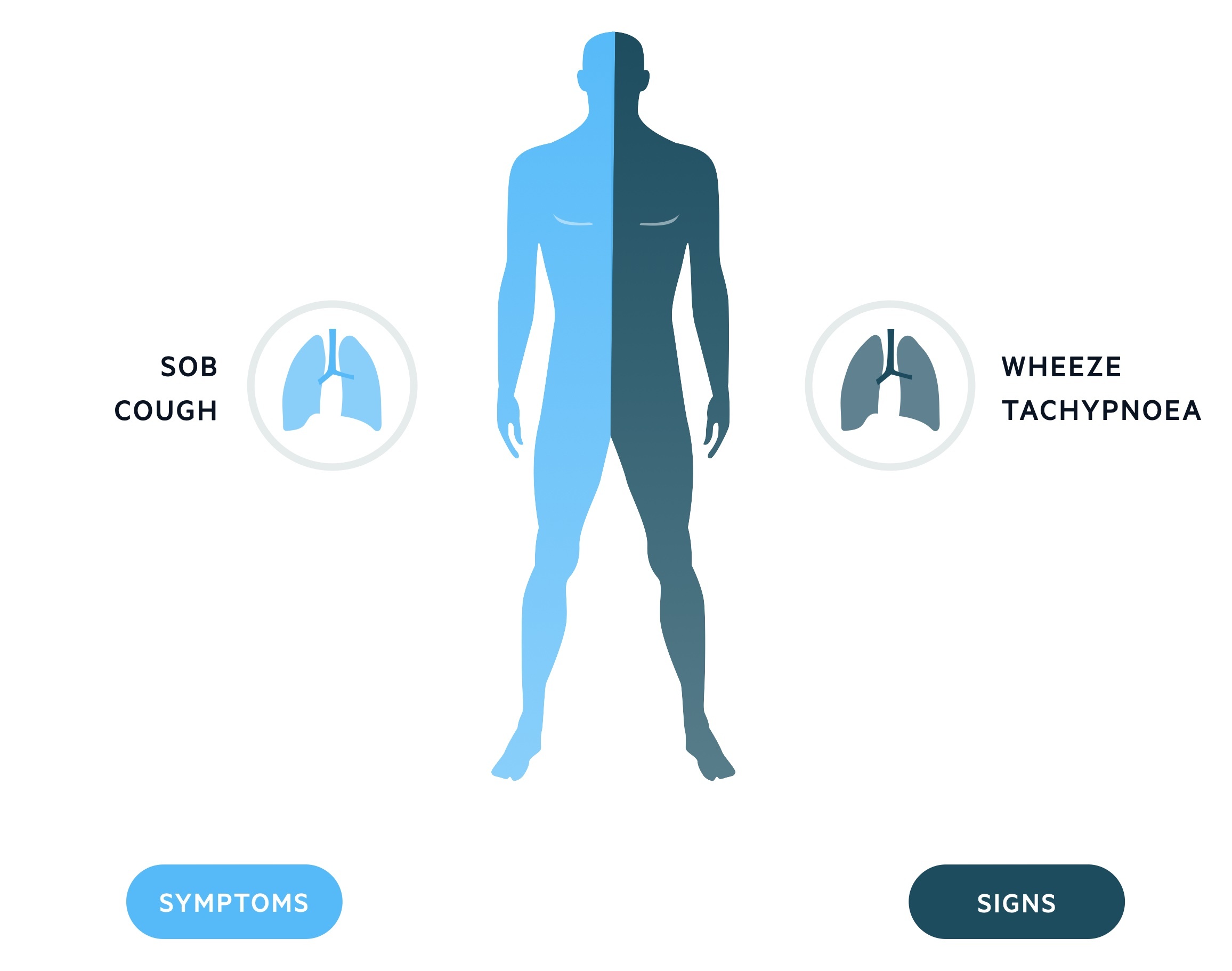

Characteristic features of asthma include cough, shortness of breath and an expiratory polyphonic wheeze.

Between acute exacerbations, some patients may experience little in the way of signs and symptoms whereas others may have chronic disabling breathlessness.

Symptoms

- Cough (may be worse at night)

- Dyspnoea

- Chest tightness

- Poor sleep

Signs

- Expiratory wheeze

- Prolonged expiratory phase

- Tachypnoea

- Harrison’s sulcus: a groove at the inferior border of the rib cage that may be seen in children with chronic severe asthma. Also seen in rickets.

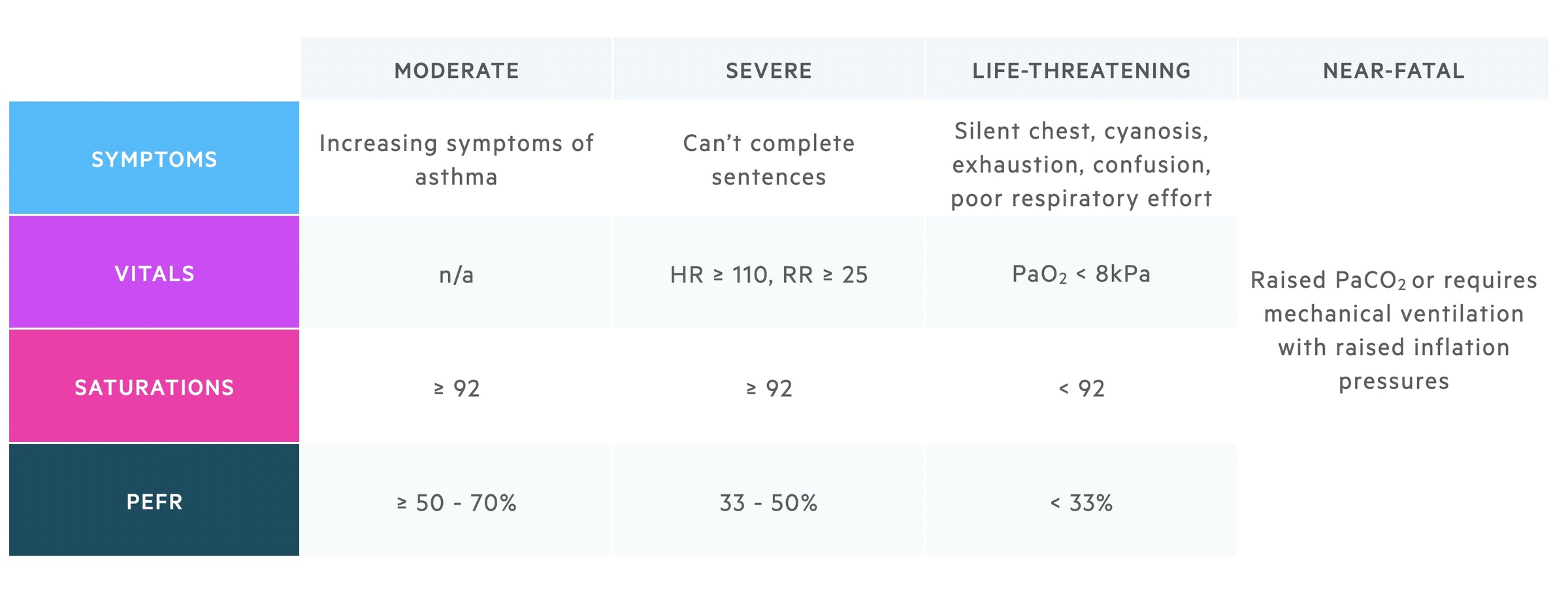

Acute asthma attack

Asthma is a chronic disease who’s course may be interrupted by acute deteriorations or ‘attacks’. These attacks are characterised by:

- Worsening of normal symptoms

- Reduction in PEF

In more severe attacks patients have signs of respiratory failure:

- Tachypnoea

- Tachycardia

- Inability to complete sentences

- Exhaustion

- Reduced respiratory effort

- Silent chest

- Altered conscious level

These features can be used to categorise the severity of an asthma attack as seen in the below table.

Spirometry, PEFR and FeNO

Spirometry should always be performed at the time of diagnosis to assess airway obstruction.

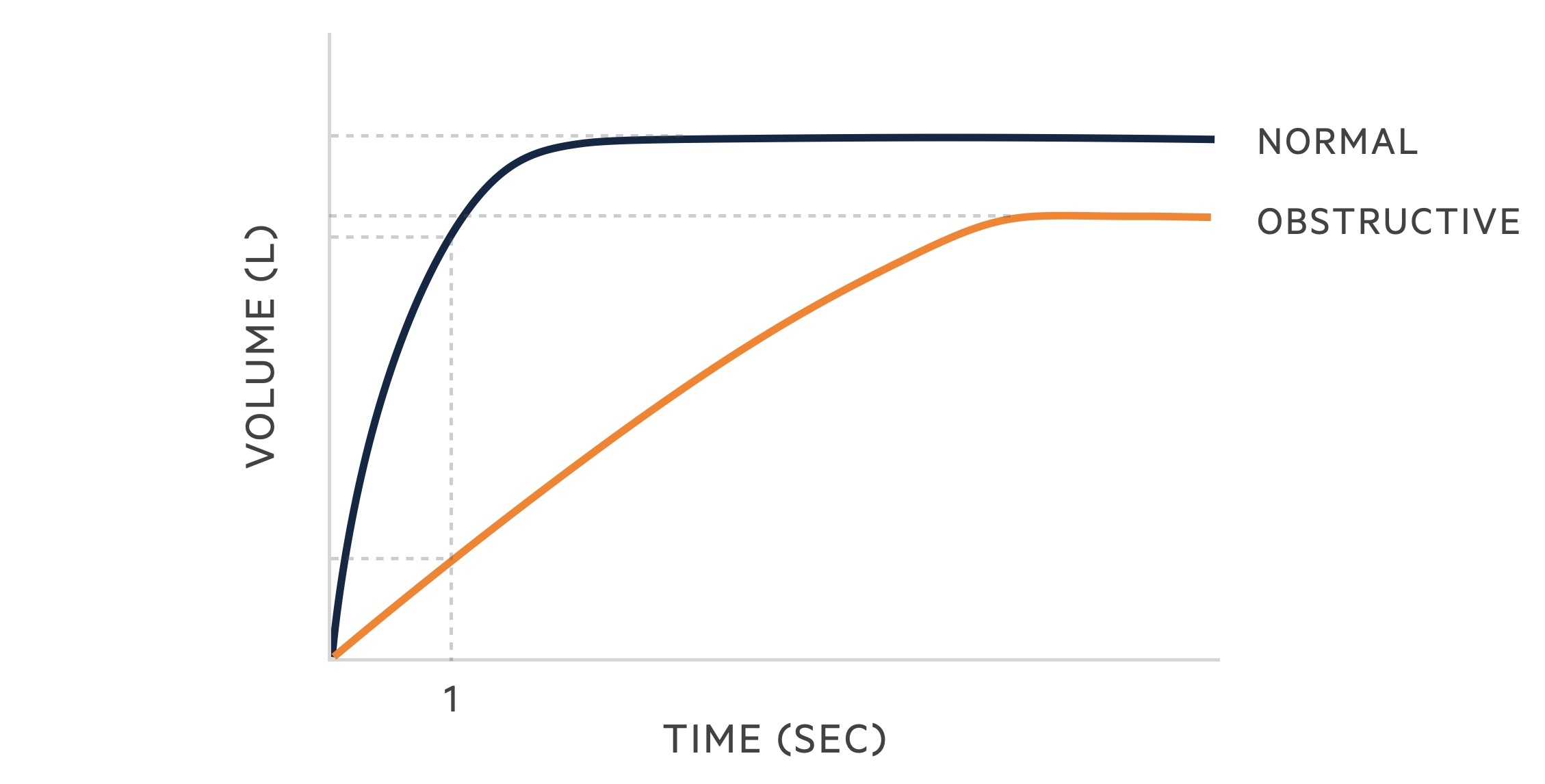

Spirometry

Spirometry measures the flow and volume of air during inhalation and exhalation:

- FVC: the forced (expiratory) vital capacity is a persons maximal expiration following full inspiration.

- FEV1: the forced expiratory volume in one second, i.e the volume of FVC expelled after one second.

The following changes are seen in obstructive lung disease:

- FVC: may be normal but often reduced due to air trapping.

- FEV1: reduced.

- FEV1/FVC: < 70%.

Reversibility may be demonstrated by performing spirometry before and after the administration of a bronchodilator.

PEFR

Asthma demonstrates characteristic variability on PEFR diaries. It usefulness in the diagnosis of asthma is limited.

It is considered non-specific as variability may be seen in other conditions. It may be used to categorise acute asthma attacks and can be key to the diagnosis of occupational asthma.

Fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO)

FeNO testing is typically offered to patients being investigated for asthma at the same time as spirometry. FeNO is a newer way of testing for eosinophilic airway inflammation. FeNO is measured in parts per billion and a level >25 ppb at 50 ml/sec is seen in 70-80% of patients with untreated asthma. Eosinophilic airway inflammation has been linked to the response to corticosteroids.

In the NICE guidelines (NG80) FeNO has an important role in the diagnosis of asthma in adults. In the BTS/SIGN guidelines it is more targeted to patients with an intermediate risk of asthma. Based on NICE guidance, we can think of FeNO measurements in three groups.

- FeNO > 40 ppb: supports a diagnosis of asthma

- FeNO 25-39 ppb: suggestive of a diagnosis of asthma. Peak flow variability useful.

- FeNO < 25 ppb: does not support a diagnosis of asthma

Asthma guidelines

BTS, SIGN & NICE have all produced guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma.

- NICE NG 80: Asthma: diagnosis, monitoring and chronic asthma management (2017, updated 2021)

- BTS/SIGN 158: British guideline on the management of asthma (revised 2019)

These guidelines provide broadly similar advice for the diagnosis and treatment in adults. However, due to the methodology used in the creation of these guidelines, there are key differences relating to both diagnosis and management. Consequently, all three have committed to producing a joint guideline, which should help unify the management of asthma.

GINA guidelines

The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) have recently produced a report on recommendations for the management and prevention of asthma in 2021. This highlighted the overuse of short-acting beta agonists (e.g. salbutamol) and made suggestions for the step-wise treatment of asthma that differs from the previous NICE and BTS/SIGN guidelines. Unfortunately, this continues to add to the confusion of the optimum treatment of asthma.

Diagnosis and investigations

Asthma is diagnosed in the presence of indicative clinical features and the exclusion of alternate diagnoses.

The diagnosis and subsequent investigations for suspected asthma in adults may differ between the NICE and BTS/SIGN guidelines.

Initially, it is important that all patients have a structural clinical assessment including history and examination to determine the probability of asthma. This is true between both guidelines. Here, we discuss the BTS/SIGN guidelines.

BTS/SIGN guidelines advise categorisation of patients based upon the probability of asthma being the correct diagnosis. From here the choice of further investigations may be made.

1. Low

Investigate and treat for alternative, more likely, diagnosis. If alternative diagnosis unlikely, investigate as an intermediate probability of asthma.

2. Intermediate

Refer for lung function testing (e.g. spirometry and bronchodilator reversibility). Additional testing may be considered to assess for variability and eosinophilic inflammation.

- Variability: reversibility testing, PEFR charts, challenge tests

- Eosinophilic inflammation: FeNO testing, blood eosinophilia, skin-prick testing

Treatment can then be instigated based on the results of investigations

- Tests indicative of asthma: commence treatment and reassess as if high probability.

- Tests not indicative of asthma: consider alternate diagnoses and specialist referral.

3. High

Trial of treatment and reassess using lung function testing or a validated scoring system.

- Improvement: continue treatment. Arrange ongoing review, provide self-management advice.

- No improvement: assess concordance and inhaler technique. Consider specialist referral and further investigations.

Specialist referral

When the diagnosis of Asthma is unclear, further investigations or specialist referral may be required.

At any point during the diagnostic algorithm within the BTS/SIGN guidelines, there may be need for further investigations or specialist referral.

Criteria for referral:

- Diagnosis unclear

- Suspected occupational asthma

- Poor response to treatment

- Severe/life-threatening attack (following acute attack)

Features suggesting alternative diagnosis:

- Systemic features (e.g. myalgia, fever, weight loss)

- Unexpected clinical findings (e.g. clubbing, cyanosis, cardiac disease, stridor/monophonic wheeze)

- Persistent non-variable breathlessness

- Chronic sputum production

- Restrictive pattern on spirometry (unexplained)

- X-ray shadowing/abnormality

Chronic management (principles)

Asthma management is a step-wise process with advancement indicated by ongoing symptoms.

The general principles of asthma management are to start at the most appropriate level of therapy, achieve early control and then maintain control.

Each of the guidelines (BTS/SIGN, NICE, GINA) outline different stepwise treatment recommendations. We have outlined below the BTS/SIGN guidelines, which are widely used in clinical practice. It is important that you know some of the key differences between the guidelines.

Control is defined as:

- Clinical: no daytime symptoms, night-time waking or activity limitation (inc. exercise)

- Acute: no asthma attacks and no need for rescue medication

- Medications: no need for rescue medication, minimal side-effects from medication

- Lung function: normal (PEF/FEV1)

Inhaled therapy

There are many different inhalers that can be used in the treatment of asthma. Inhalers may contain a single drug (e.g. beta-agonist) or combination of drugs (e.g. beta-agonist and corticosteroid).

Drug classes

- Beta-receptor agonists: bind to beta receptors of the sympathetic nervous system. Causes relaxation of airway smooth muscle and subsequent bronchodilation. May be short or long-acting.

- Corticosteroids: inhaled corticosteroids work by reducing inflammation within the lungs. They are thought to reduce the number of exacerbations and improve the efficacy of bronchodilators

Inhaler types

- Short-acting beta-agonists (SABA): Salbutamol

- Long-acting beta-agonists (LABA): Salmeterol

- Inhaled corticosteroid (ICS): Beclomethasone

- LABA-ICS: Seretide (salmeterol/fluticasone)

Delivery devices

Inhalers may deliver drugs by different mechanisms

- Metered dose inhalers (MDI): delivers a specific amount of medication to the lungs by a short burst of aerosolised medicine. Patient dependent, requires good breath and coordinating activation with breath. Many patients have poor technique.

- Dry powder inhaler (DPI): usually requires ‘loading’ or ‘activation’ of the device for the powder to be administered. Requires good force of patient inhalation and need to hold breath for certain period.

- Soft mist inhaler (SMI): contain liquid formulations of the drug. More drug delivery to lungs and less coordination needed compared to MDI inhalers.

- Spacers: typically used with a MDI inhaler to enhance drug delivery and reduce need for good coordination. Contains a chamber that the drug is delivered into and the patient then completes normal tidal breathing to inhale the drug.

- Nebuliser: drug in liquid form is converted into a mist using a nebuliser machine with compressed air. Typically reserved for patients with an acute exacerbation in hospital or disabling symptoms despite maximal inhaler therapy.

Chronic management (drugs)

Pharmacological treatment of asthma follows a step-wise algorithm.

Traditionally, all patients are offered a short-acting beta-2 agonist (SABAs) such as salbutamol (a reliever). This is prescribed as needed (PRN) and if use exceeds three times a week consider ‘stepping up’ therapy. However, newer guidelines focus on early initiation of an ICS. It is important to only prescribe inhalers following training on how to use the device and demonstration of satisfactory technique.

The first step in the SIGN/BTS guidelines is an ICS with SABA as needed. Alternatively, a patient may use a LABA (e.g. formoterol) combined with an ICS as part of a maintenace and reliever inhaler (i.e. MART). These LABAs are relatively short-acting and can be taken for relief of symptoms as required and reduce the need for multiple inhalers.

The below stepwise algorithm follows the SIGN/BTS guidelines. We also mention the newer recommendations on chronic asthma management recommended by GINA.

Step 1: regular preventer

Prescribe an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) as part of a monitored trial in those with suspected asthma or to those formally diagnosed with asthma. Examples include Fluticasone and Beclomethasone.

Step 2: initial add-on therapy

Add inhaled long-acting beta agonist (LABA) in addition to low dose ICS. Can consider fixed doses or use of maintenance and reliever therapy (MART), which refers to a combined inhaler. Fostair is an example of a MART that contains formoterol/beclometasone.

A MART should be used daily as maintenance, but can also be used when patients develop symptoms. If patients are using a MART they should not be dually prescribed a SABA (e.g. salbutamol).

Step 3: additional therapies

Consider increasing ICS to medium dose or adding a leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA) like montelukast. One of the major differences in the NICE guidelines refers to the role of LRTAs (they recommend this at step 2).

Step 4: consider specialist referral

If ongoing symptoms despite previous therapies, consider specialists referral.

GINA recommendations

GINA have advised their own step-wise recommendations that follows two tracks depending on the role of the ‘reliever’ inhaler:

- Track one:

- Step 1-2: as needed low dose ICS + LABA (formoterol)

- Step 3: maintenace ICS + LABA

- Step 4: increase maintenace ICS + LABA

- Step 5: Add LAMA / further increase maintenace ICS + LABA / referral for consideration alternative therapies

- Track two:

- Step 1: take ICS whenever SABA taken for relief

- Step 2: low dose maintenance ICS

- Step 3: low dose maintenance ICS + LABA

- Step 4: medium/high dose maintenance ICS + LABA

- Step 5: Add LAMA / further increase maintenace ICS + LABA / referral for consideration alternative therapies

Acute management

A severe acute asthma attack represents a medical emergency. Prompt recognition and management is required.

The severity of an acute asthma attack is based on symptoms, observations and the PEFR, this is described in the table in the ‘Clinical features’ chapter. Patients will generally receive their initial therapy in A&E Resus or majors depending on presenting features. ITU/HDU input should be arranged early in those with severe features.

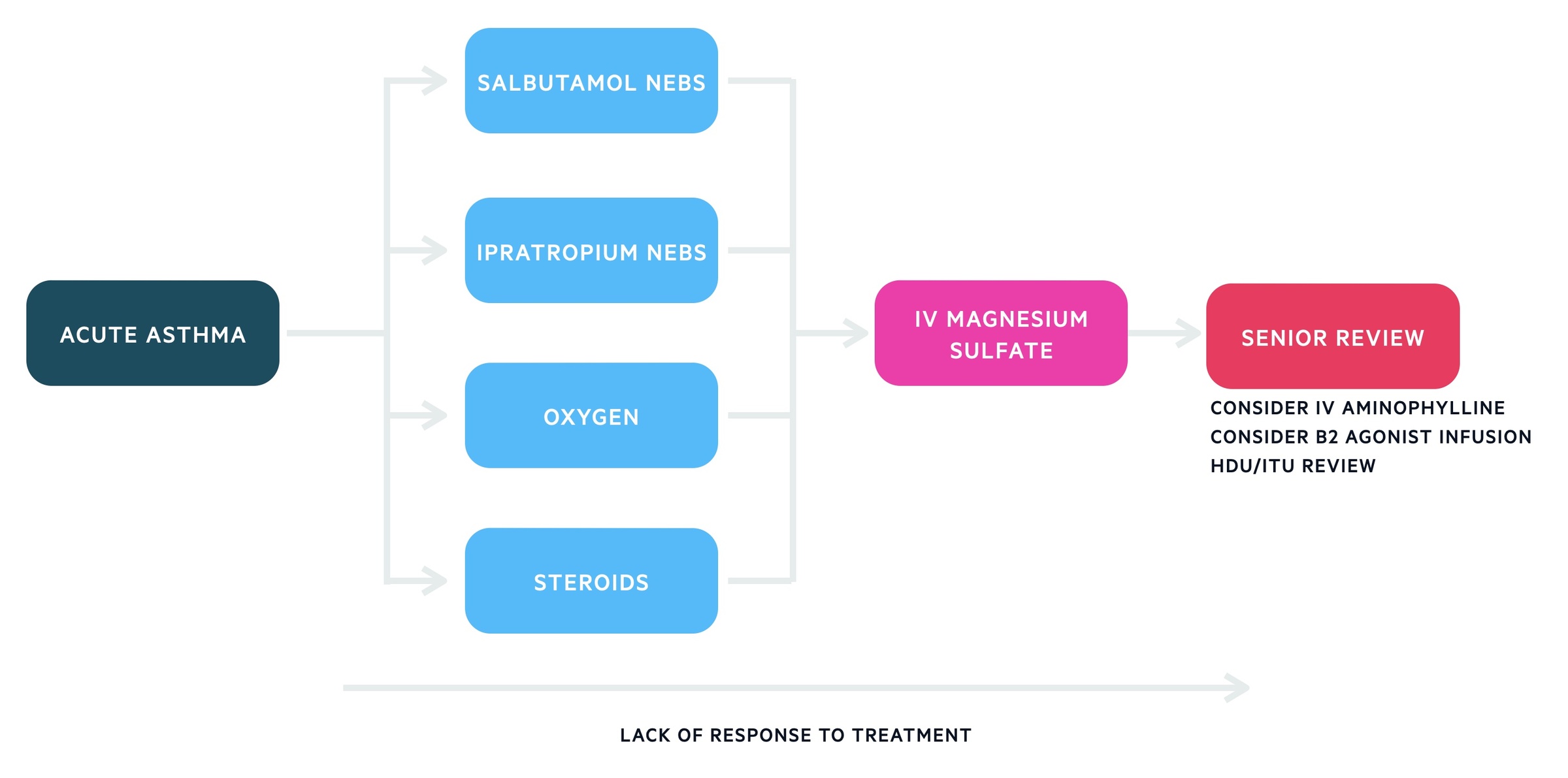

Acute asthma management

The below algorithm is based on SIGN/BTS 158 guideline on the management of asthma. Patients not responding to first line therapies need senior clinician review and discussion with HDU/ICU.

1. Initial management

Salbutamol

Salbutamol nebulisers, 2.5 – 5mg (preferably driven by oxygen) should be administered in adults. They may be repeated every 15 to 30 minutes. If there is no access to nebulisers back to back inhalers should be given. IV beta-2 agonists should be reserved for those in whom inhaled therapy is not possible.

Oxygen

Oxygen should be started immediately in severe attacks and is typically titrated to saturations of 94-98%. An arterial blood gas should be considered if saturation < 92% or life-threatening features. The development of hypercapnia indicates a near-fatal attack, specialist and anaesthetic involvement is required.

Steroids

Steroids should be started. Either PO with prednisolone 40-50mg daily or IV with hydrocortisone 100mg six hourly. They should be continued for at least five days. In cases where IV hydrocortisone has been used, switch to oral prednisolone when appropriate.

Ipratropium bromide

Ipratropium bromide nebulisers, 0.5 mg 4-6 hourly, are given to most patients admitted with an acute asthma attack. However, it is advised for patients with severe or life-threatening asthma not responding to nebulised salbutamol.

2. Second line therapies

Magnesium sulfate

There is a body of evidence indicating magnesium sulfate has bronchodilator effects. Discussion with senior staff is necessary, a dose of 1.2 – 2 g IV magnesium sulfate may be given over 20 minutes in adults.

Beta 2 agonist infusion

In patients still not responding B2 agonist infusions may be started.

Aminophylline

In an acute attack, there is little evidence IV aminophylline will result in additional bronchodilation.

It is often still used and requires senior input. A 5mg/kg loading dose (over 20 minutes) is followed by a continuous infusion. Aminophylline levels should be checked daily.

Follow-up and discharge

Patients who have suffered a near-fatal acute exacerbation of asthma require specialist follow-up indefinitely.

The SIGN/BTS guidelines provide information about appropriate discharge of patients from the emergency department who present with an acute exacerbation of asthma.

Discharge criteria

- Consider early discharge at 20 minutes: clinically stable, no life-threatening or severe features and peak flow >75% of best or predicted.

- Consider discharge at 60 minutes: patient recovering, no signs of life-threatening or severe asthma, peak flow >75% of best or predicted. Consider further observation if any concern.

- Consider discharge at 2 hours: patient stable, no signs of life-threatening or severe asthma, peak flow >50% of best or predicted. Consider further observation if any concern.

- Admission: any features of life-threatening asthma, ongoing features of severe asthma or peak flow <50% of best or predicted

If require nebulised beta-2 bronchodilators prior to presentation, consider extended period of observation.

NOTE: Once admitted to hospital the key parameter to determine discharge is peak flow. The aim should be a peak flow >75% of best or predicted with a diurnal variability <25% before discharge (unless agreed otherwise by a respiratory clinician).