Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS)

This refers to widespread inflammation at the alveolar-capillary interface, increasing the permeability of the alveolar capillaries.

Fluid moves out of the permeable capillaries, resulting in non-cardiogenic pulmonary oedema that impairs ventilation.

ARDS can progress to organ failure and carries a high morbidity and mortality risk.

Causes

Direct – this is due to direct lung injury (such as smoke inhalation)

Indirect – due to conditions which cause inflammation (such as sepsis, shock and acute pancreatitis)

Symptoms

Acute onset tachypnoea, dyspnoea

Bilateral inspiratory crackles

Low oxygen saturations and cyanosis with respiratory distress

Key tests

ABG shows hypoxia which maybe resistant to oxygen therapy

CXR/CT – shows bilateral infiltrates

Echocardiogram – needed to rule out cardiac failure

Diagnosis

There are 4 key criteria for diagnosing ARDS:

Acute onset (within 1 week of a known risk factor)

Bilateral infiltrates (e.g., pulmonary oedema) not explained by other lung pathology

Respiratory failure not due to heart failure

Decreased PaO2/FiO2 ratio (< 40 kPa): indicates poor oxygenation

Management

This requires cardiorespiratory support whilst you correct the underlying cause

Respiratory support – low tidal volume mechanical ventilation

Cardiac support – maintain cardiac output with inotropes and vasodilators

Pneumothorax

This refers to an accumulation of air in the pleural space. It can be classified as:

Primary

This occurs in a patient without a known respiratory disease, usually due to rupture of a subpleural air bulla (typically affects young, thin men).

Secondary

This occurs in a patient with a chronic respiratory disease. The aetiology depends on the underlying disease (e.g., in cystic fibrosis, endobronchial obstruction by mucus leads to increased pressure in the alveoli, leading to alveoli rupture).

Tension

This occurs due to a penetrating chest wall injury and is an emergency. The injury acts like a one-way valve, which allows air to enter but not escape the pleural space.

As more air enters the pleural cavity, this can lead to compression of the SVC/IVC, leading to haemodynamic compromise and death.

Signified by deviation of the trachea and mediastinum away from the affected side.

Risk factors

Lung disease (asthma, COPD)

Trauma, i.e., can be iatrogenic e.g., mechanical ventilation, central line insertion

Connective tissue diseases (Marfan)

Catamenial pneumothorax, due to endometriosis in menstruating women

Symptoms

Dyspnoea

Tachycardia, tachypnoea

Pleuritic chest pain

Signs

Reduced lung expansion

Reduced breath sounds and hyperresonant percussion on affected side

Key tests

CXR shows lung markings do not reach chest wall

Management

For Tension

If you suspect a tension pneumothorax, you should treat before getting a CXR

Insert a 14 G cannula into the 2nd intercostal space mid-clavicular line and subsequently insert a chest drain

For Spontaneous

Management used to depend on the size of the pneumothorax, which guided whether to monitor the patient, needle aspirate or insert a chest drain

The latest guidance by the British Thoracic Society focuses more on whether the patient is symptomatic and whether they can be managed conservatively

Asymptomatic – conservative management (review regularly as outpatient)

Symptomatic and high-risk characteristics (e.g., hypoxia, underlying lung disease, if age > 50 years old with significant smoking history) – needle aspiration or chest drain

Symptomatic without high-risk characteristics – management is guided based on patient preference (e.g., procedure avoidance if they wish for this)

Anaphylaxis

This refers to a life-threatening hypersensitivity reaction.

It arises within seconds-minutes of exposure to the allergen, due to excessive mast cell degranulation releasing vast amounts of histamine.

Common allergens include food (nuts, dairy, shellfish); medications (including penicillin) and blood transfusions.

Symptoms

Respiratory – bronchospasm with dyspnoea and wheezing

Cardiovascular – distributive shock, i.e., hypotension with tachycardia

Skin – angioedema and urticarial rash with pruritus

ENT – tongue swelling and laryngeal oedema (can obstruct the airway)

Management

The most important immediate treatment is intramuscular adrenaline.

Hydrocortisone and Chlorphenamine are used after the IM adrenaline is given.

Patients should be observed for 6–12 hours from symptom onset, as a biphasic reaction can occur in about a fifth of patients.

To determine whether it is true anaphylaxis, serum tryptase levels are taken between 4–12 hours after onset of anaphylaxis (should be raised).

Patients require monitoring in a high dependency area due to risks of cardiovascular collapse and further deterioration.

Carbon Monoxide Poisoning

This is an acute condition which occurs due to the inhalation of carbon monoxide.

It commonly occurs in house fires and in poorly maintained housing.

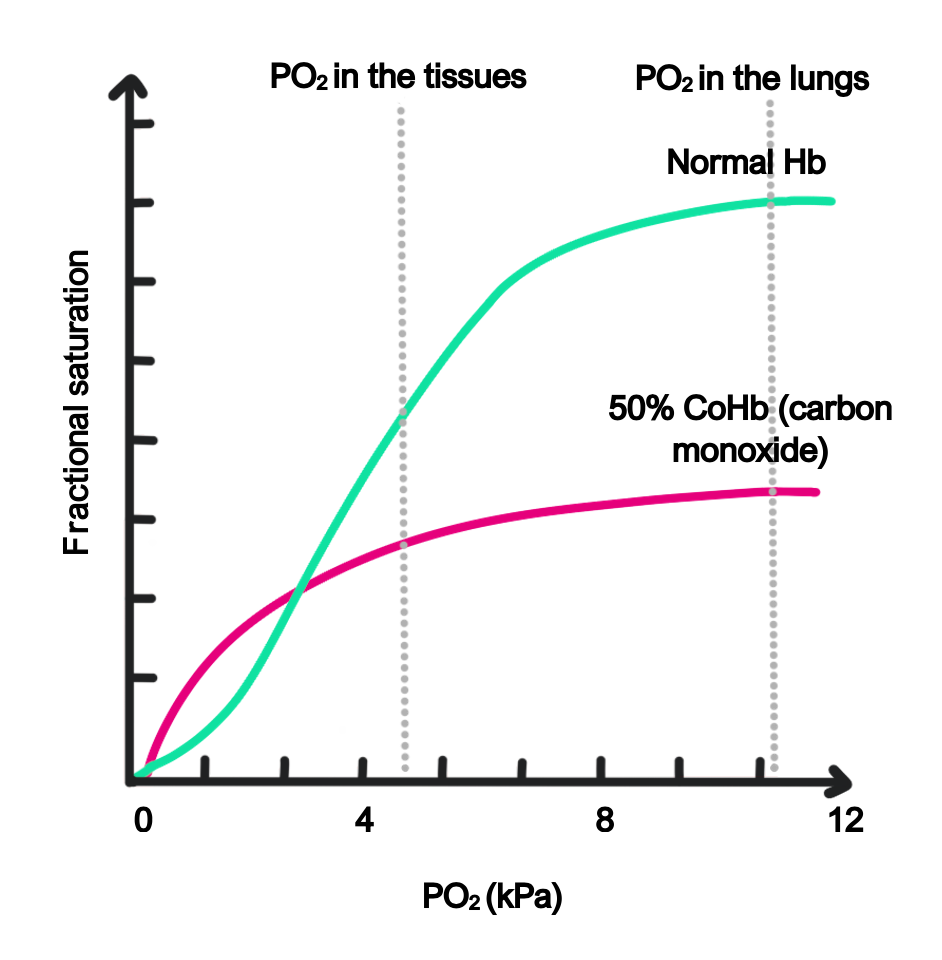

CO has greater affinity for haemoglobin than O2, reducing haemoglobin’s ability to deliver O2 to the respiring tissues.

Carbon monoxide binds haemoglobin to form carboxyhaemoglobin (COHb):

In non-smokers, the ratio of carboxyhemoglobin to haemoglobin can be up to 5%

In smokers, levels of COHb are usually < 10%

In symptomatic CO poisoning, COHb is usually between 10–30%

In severe toxicity, COHb is > 30%

Symptoms

Headache

Nausea, vertigo and confusion

Can cause arrhythmias, fever, reduced consciousness and death

“Pink” skin and mucosae

Management

100% oxygen (target SpO2 is 100%)

Consider hyperbaric oxygen, especially if there is loss of consciousness, neurological signs or the patient is pregnant

Pleural effusion

This is defined as fluid in the pleural space which surrounds the lungs, divided into transudate and exudate:

Transudate

This is fluid in the pleural space which has < 25 g/L protein.

It is caused by increased hydrostatic pressure in the pleural capillaries (increased fluid in the capillaries) or decreased oncotic pressure (reduced albumin/protein).

This forces water out of the capillaries into the pleural space.

Causes

Heart failure (most common cause)

Hyperalbuminemia (e.g., secondary to nephrotic syndrome liver failure)

Hypothyroidism

Meigs syndrome – triad of ovarian fibroma and ascites with pleural effusion

Exudate

This refers to fluid which has > 35 g/L protein. It occurs due to increased leakiness of pleural capillaries, which allows protein into the pleural space.

Causes

Infection, e.g., pneumonia (most common cause), TB, abscess

Connective tissue diseases, e.g., SLE, rheumatoid

Malignancy

Symptoms

Effusions can be asymptomatic if small

Shortness of breath, dry cough and pleuritic chest pain

On examination, reduced chest expansion, breath sounds and stony dull percussion

Key tests

CXR – this shows blunting of the costophrenic angles

Ultrasound – shows presence of pleural fluid

Pleural tap – the diagnostic test which involves aspiration using a fine needle. This is sent to the lab for biochemistry analysis (e.g., checking for malignant cells) and microscopy, culture and sensitivity (MC&S).

Management

If symptomatic or evidence of empyema, a chest drain maybe required.

Treat the underlying cause, e.g., antibiotics for pneumonia

Patients with recurrent pleural effusions may need pleurodesis, which is a procedure that binds the 2 visceral and parietal pleurae together, stopping fluid from reaccumulating in the space between them.