Overview

The ‘glomerulopathies’ are a constellation of diseases characterised by injury to renal glomeruli.

Glomerular disease (also known as ‘glomerulonephritides’ or ‘glomerulopathies’) refers to a group of conditions that cause damage to the renal glomeruli. The glomeruli represent the site of filtration (i.e. where blood is filtered) within the kidneys. Glomerular diseases are an important cause of both acute kidney injury (AKI) and chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Glomerular diseases are traditionally difficult to learn. This is because of confusing terminology that combines clinical and histopathological terms, the wide variety of clinical presentations and significant overlap between conditions. Two commonly discussed clinical manifestations of glomerular disease are ‘Nephrotic syndrome’ and ‘Nephritic syndrome’, which are discussed in our other notes.

Here, we present a simple and easy to understand conceptual overview to the glomerular diseases.

Glomerular structure

The glomerulus is the site of ultrafiltration within the kidneys.

The kidneys are critical for normal homeostasis. They are involved in multiple functions including excretion of waste products, acid-base balance, fluid balance, calcium/phosphate balance and blood pressure control, amongst others.

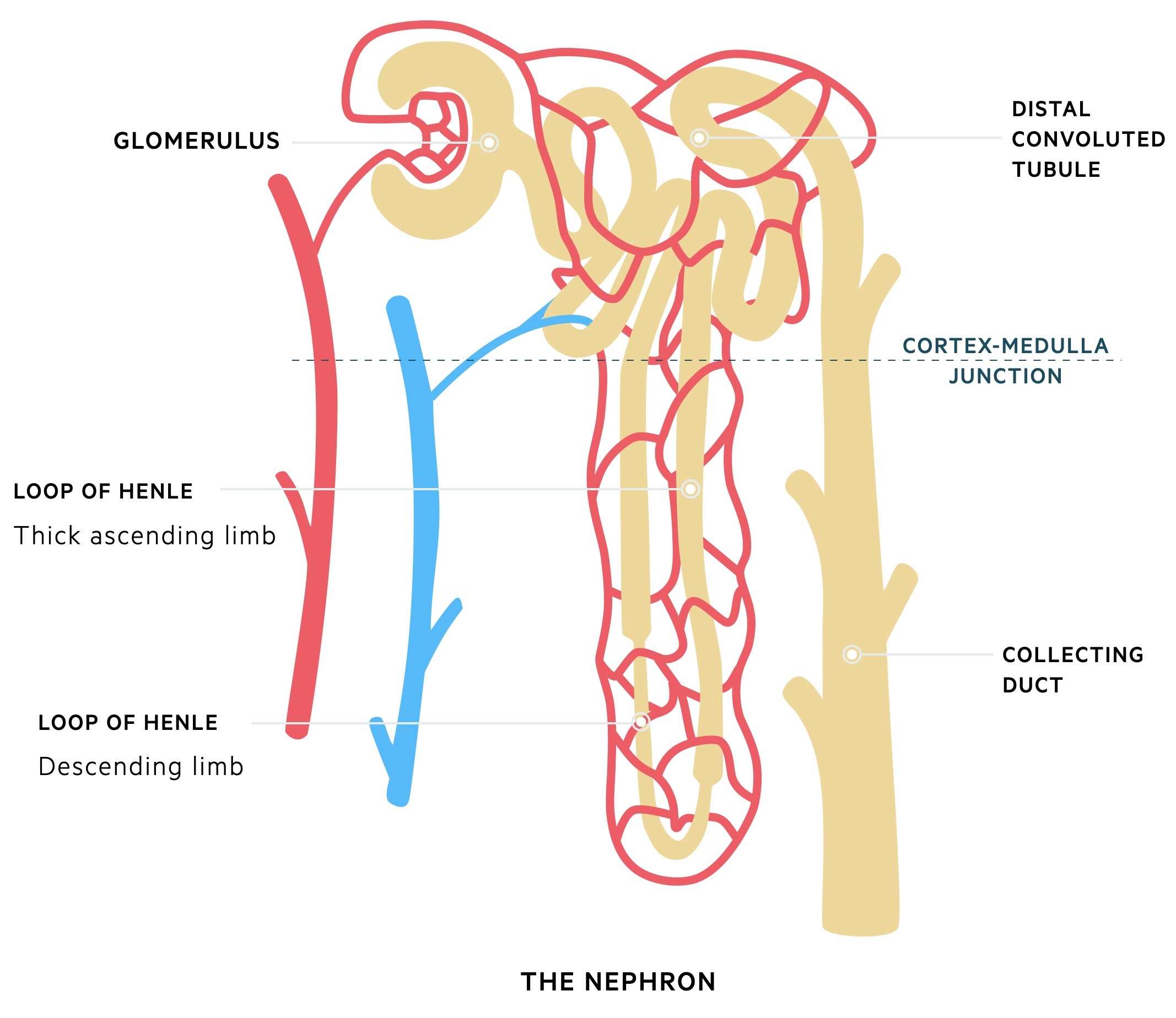

The nephron

At a microscopic level, the functional unit of the kidney is known as the nephron. The nephron is divided into several important structures involved in filtration, reabsorption and secretion.

Glomerulus

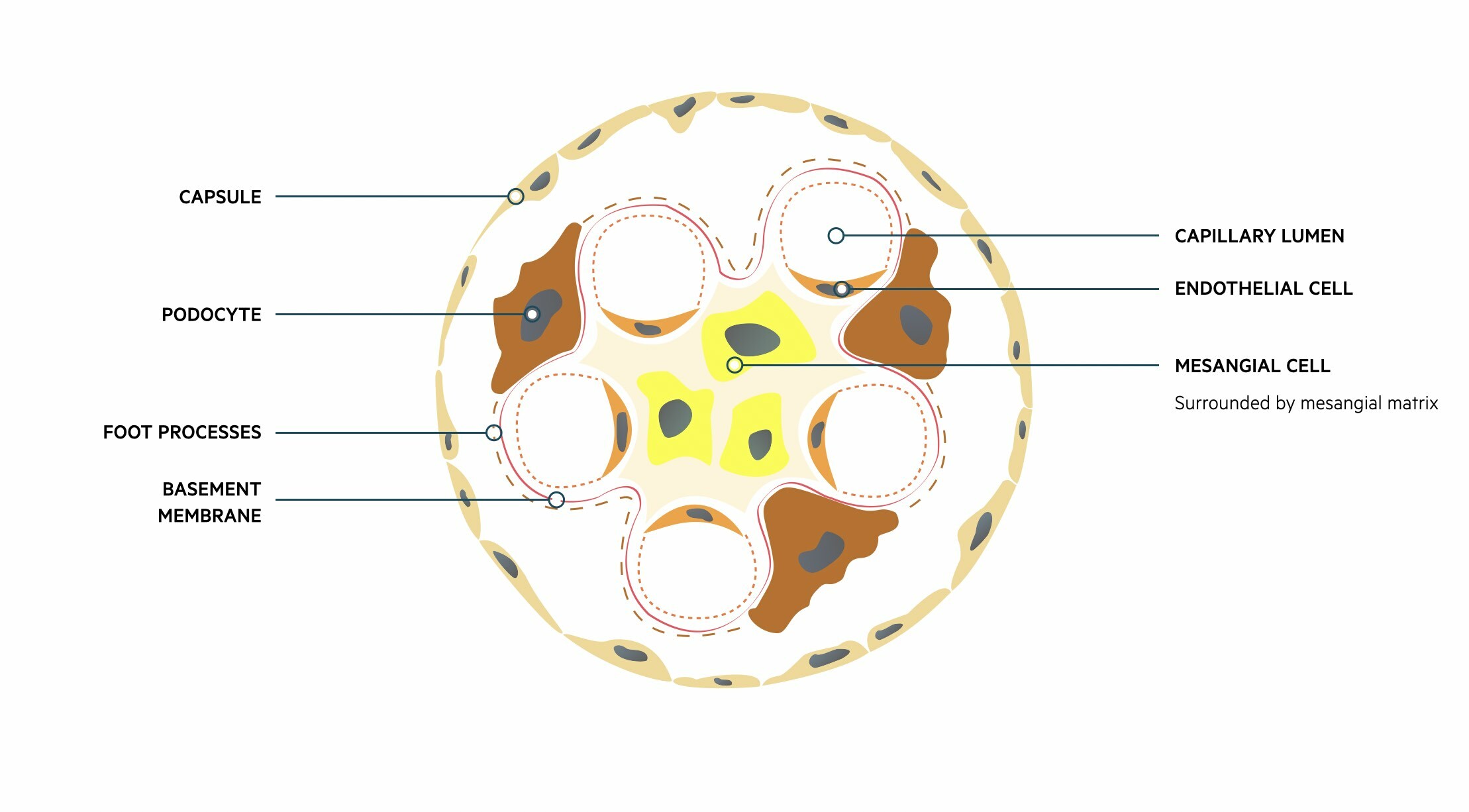

The glomeruli are important for filtration, which describes the process of removing protein free plasma from the blood. Each glomerulus contains a tuft of capillaries surrounded by a capsule (Bowman’s capsule). These capillaries are supported by a series of cells and connective tissue known as the mesangium.

Fluid and other substances may pass from the capillaries into the urinary space of the glomerulus. These subsequently pass into the proximal convoluted tubule of the nephron. This passage of fluid is regulated by three layers that make up the ‘filtration barrier’.

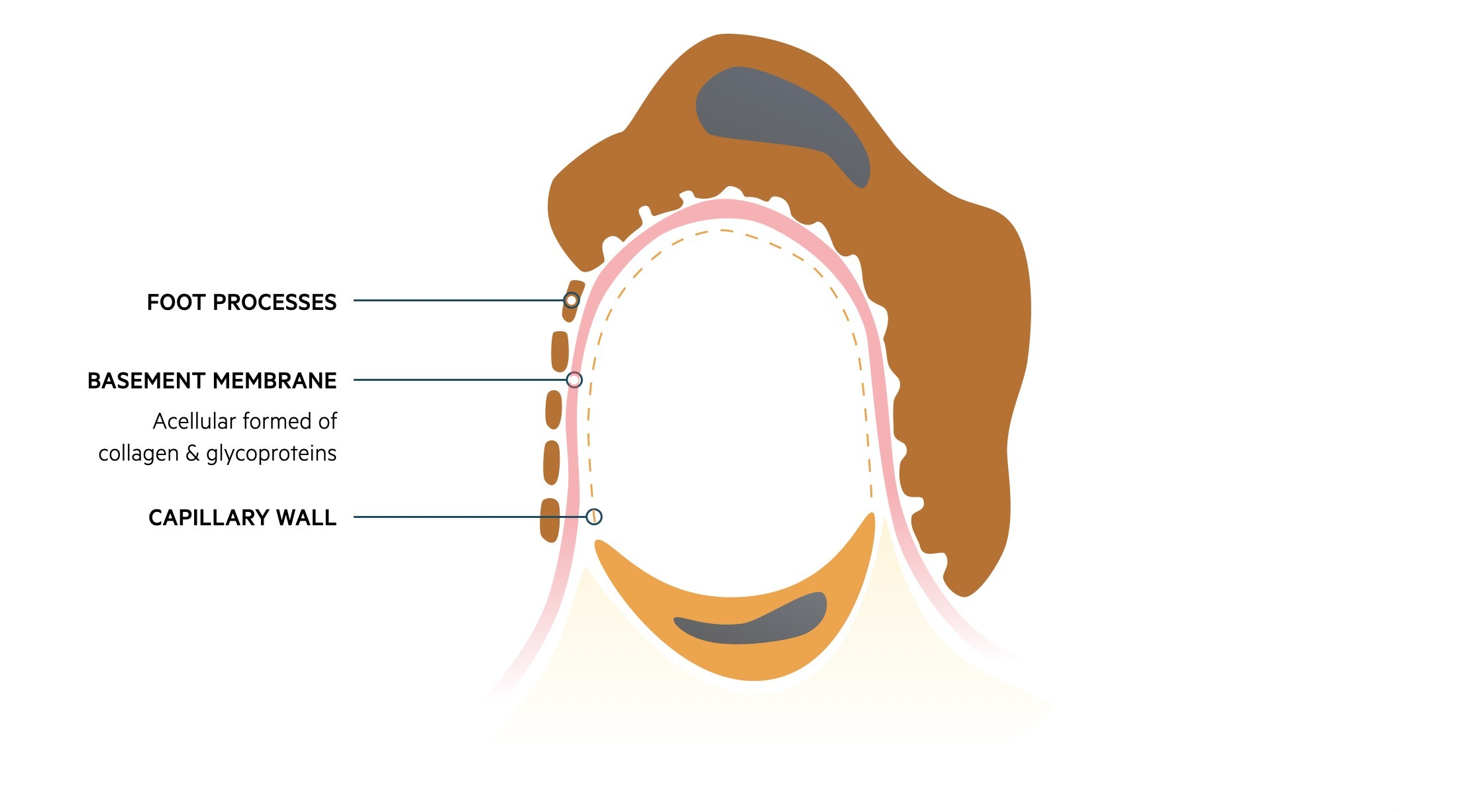

Fluid and other substances may pass from the capillaries into the urinary space of the glomerulus. These subsequently pass into the proximal convoluted tubule of the nephron. This passage of fluid is regulated by three layers that make up the ‘filtration barrier’.

- Endothelium: capillary wall

- Basement membrane: provides a selective barrier to macromolecules based on size and charge

- Foot processes of podocytes: podocytes are specialised epithelial cells

Damage to the glomeruli by structural changes or immune-mediated injury can disrupt the filtration barrier. This can lead to leakage of red blood cells (i.e. haematuria) and/or protein (i.e. proteinuria) that forms the hallmark of glomerular disease.

The filtration barrier

Classification

Glomerular disease may be broadly divided into primary or secondary disorders.

There are various ways to classify and describe glomerulopathies. Here we discuss some of the common terminology.

Primary versus secondary

Glomerular disease may be primary (glomerular injury due to a primary renal pathology) or secondary (glomerular injury occurring as part of a systemic process).

- Primary: IgA nephropathy, minimal change disease, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis

- Secondary : Vasculitis (e.g. ANCA-associated vasculitis), amyloidosis, diabetes mellitus

Confusingly, some conditions can cause both a primary glomerulopathy and a secondary glomerulopathy if it occurs in the context of another systemic illness (e.g. focal segmental glomerulosclerosis).

Focal versus diffuse

A glomerulopathy may be focal (only some glomeruli are involved) or diffuse (all glomeruli are affected). A broad cut-off of 50% is generally used to differentiate between focal or diffuse. Determining whether a glomerulopathy is focal or diffuse is based on renal biopsy and sampling of glomeruli.

Global versus segmental

A glomerulopathy may be described as global or segmental based on the amount of involvement of each individual glomerulus. Again, a broad cut-off of 50% is used to differentiate these two terms based on histopathological assessment.

Pathophysiology

A broad range of both immune and non-immune mechanisms can lead to glomerular injury.

A variety of mechanisms may lead to glomerular damage that ultimately affects the filtration barrier. A specific underlying mechanism depends on the cause of glomerulopathy.

Mechanisms of disease

The major pathological mechanisms can be divided into immune-mediated and non-immune mediated:

- Immune-mediated: deposition or in situ formation of immune complexes (collections of antibodies) that fix complement and activate a pro-inflammatory response. Alternatively, circulating antibodies may directly target key proteins on the basement membrane or endothelial cells precipitating an inflammatory reaction (e.g. ANCA-associated vasculitis).

- Non-immune mediated: the structure and/or function of podocytes may be affected that disrupts the filtration barrier (e.g. minimal change disease). This leads to larger macromolecules leaking through glomeruli. Alternatively, accumulation of non-immune material (e.g. proteins) can disrupt the glomeruli structure causing dysfunction (e.g. diabetes mellitus, amyloid).

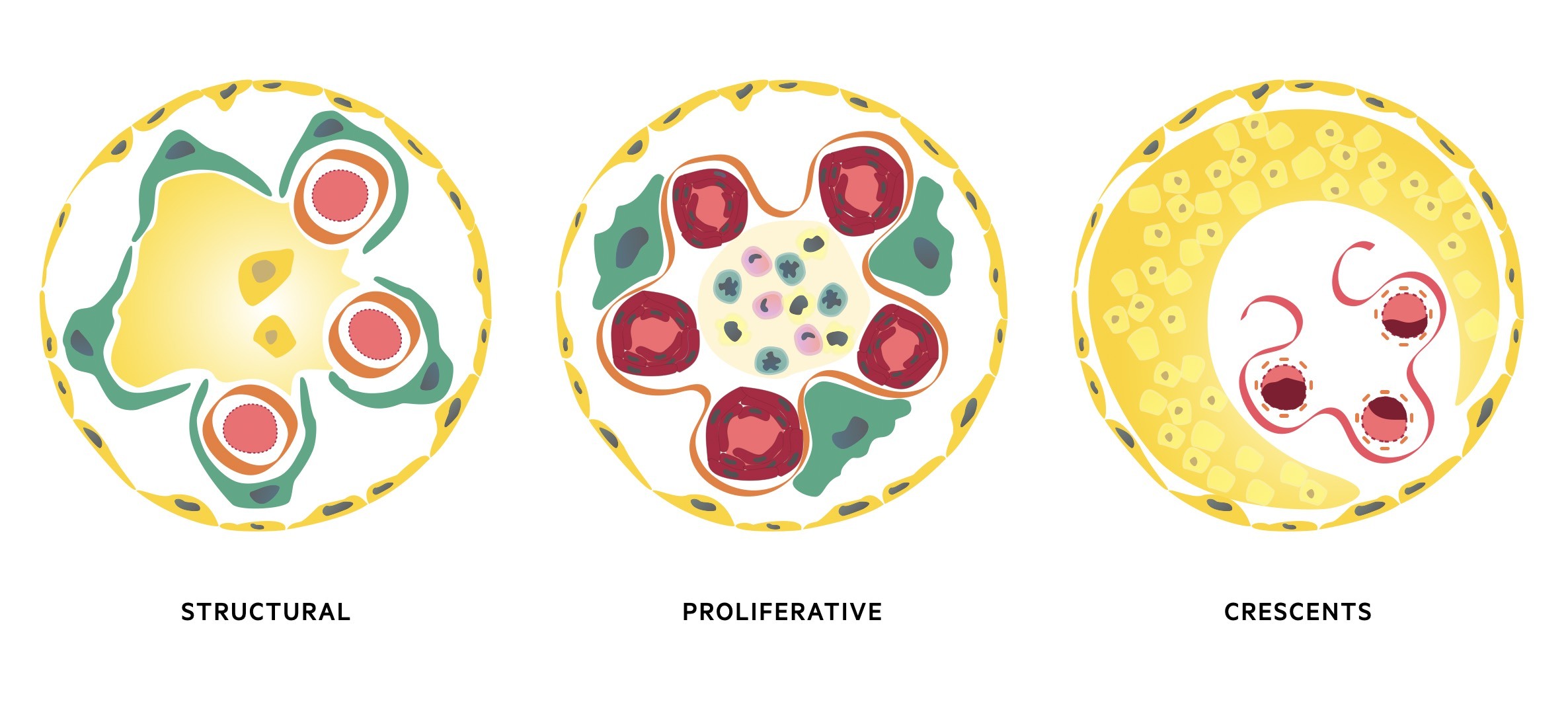

Histopathological changes

Each type of glomerular injury will often cause a specific histological disease pattern that can be observed under the microscopic. These histological changes are often associated with a specific clinical presentation.

The three major histological patterns include:

- Proliferative: increase in the number of cells in the glomerulus. May be located within the mesangium, capillary wall or outsides the capillaries in Bowan’s space. Typically associated with a marked inflammatory response due to deposition of immune complexes or antibody-binding. Causes glomerular inflammation with haematuria and/or nephritic syndrome.

- Non-proliferative (structural): glomerular damage characterised by structural changes and often sclerosis (scarring of the glomeruli). May show diffuse scarring or only subtle changes under electron microscope. Typically associated with excess protein loss and nephrotic syndrome.

- Crescents: extracapillary lesions in Bowan’s capsule due to accumulation of immune cells, fibroblasts, epithelial cels and fibrin. Crescents represent severe injury to the capillary wall that results in glomerular membrane rupture. Can be observed in any cause of inflammatory glomerular disease, but widespread crescents typically seen in rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (see below).

Clinical presentations

A large number of conditions can cause glomerular injury.

There are multiple causes of glomerular disease, which we can broadly divide based upon clinical presentation, presence of systemic features and degree of renal impairment. These groups include:

- Isolated haematuria

- Isolated proteinuria

- Nephrotic syndrome

- Nephritic syndrome (i.e. glomerulonephritis)

- Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN)

Importantly, not all conditions neatly divide into these categories. This is because some conditions may present in more than one way (e.g. IgA nephropathy can cause isolated haematuria, nephritic syndrome or rarely nephrotic syndrome).

Isolated haematuria

This refers to the recurrent presentation of haematuria.

Haematuria refers to blood in the urine that may be visible or non-visible. Isolated haematuria is broadly defined as persistent haematuria in the absence of proteinuria and normal renal function. This requires reassessment over 1-4 weeks to determine whether haematuria is persistent.

Typical causes include:

- IgA nephropathy

- Alport syndrome

- Thin basement membrane disease: diffuse thinning of the basement membrane on electron microscopy. May be familial in up to 50% of cases

Importantly, blood may occur from any location along the urinary tract. Therefore, it is important exclude other causes before confirming isolated haematuria (e.g. imaging, cystoscopy). Features that are suggestive of blood from glomerular origin include:

- Dysmorphic red blood cells: red cell structure appears abnormal under the microscope

- Red blood cell casts: identification of red bloods cells within urinary casts seen under the microscope. A cast is a microscopic cluster of particles wrapped in uromodulin (Tamm-Horsfall protein). Uromodulin is secreted by epithelial cells lining the loop of Henle, distal tubule & collecting duct.

Isolated proteinuria

The refers to the persistent presence of protein in the urine.

Proteinuria refers to the presence of protein in the urine that may be glomerular, tubular, overflow (i.e. myeloma) or post-renal in origin. Isolated proteinuria is broadly defined as persistent proteinuria in the absence of other urinary abnormality (e.g. haematuria), co-morbidities (hypertension & diabetes) and in the presence of normal renal function.

The degree of proteinuria is non-nephrotic range (i.e. < 3.5 g/day) and can be detected with urine dipstick, spot urinary protein:creatinine ratio or a 24-hour urinary collection. Persistent isolated non-nephrotic range proteinuria usually indicates underlying renal disease or a systemic disorder that needs further investigation.

It is important to exclude more benign causes of proteinuria including:

- Transient proteinuria: common in young individuals. Absent on repeat testing and exercise is a common precipitant.

- Orthostatic proteinuria: presence of proteinuria only in the upright position

Nephrotic syndrome

Nephrotic syndrome is broadly defined as a triad of heavy (nephrotic range) proteinuria > 3.5 g/day, hypoalbuminaemia (< 35 g/L) and peripheral oedema. The condition may also be accompanied by hyperlipidaemia and thrombotic disease (venous and arterial blood clots).

In marked fluid overload, patients may develop ascites and pleural effusions. Acute kidney injury can occur, but is less commonly observed compared to glomerulonephritis.

The causes of nephrotic syndrome can be broadly divided into primary renal disorders and secondary systemic conditions.

- Primary: minimal change disease, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), membranous nephropathy.

- Secondary: diabetes mellitus, amyloidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, HIV infection

For more information see our note on Nephrotic syndrome.

Nephritic syndrome (i.e. glomerulonephritis)

Nephritic syndrome is classically described as the presence haematuria, variable proteinuria (may be nephrotic range), oliguria (i.e. acute kidney injury) and hypertension. The term ‘nephritic syndrome’ is often used interchangeably with nephritis or glomerulonephritis simply referring to inflammation within the glomeruli.

Glomerulonephritis has quite a variable clinical presentation.

- Mild: presentation with minimal haematuria and proteinuria only

- Severe: typically presents with the classical ‘nephritic syndrome’

- Self-limiting: development of an acute glomerulonephritis that gets better without treatment

- RPGN: severe glomerulonephritis that has a fulminant course with rapid deterioration in renal function over days to weeks to a few months.

- Chronic: slowly progressive renal disease presenting with features of CKD

There are three major causes of nephritic syndrome:

- Immune complex deposition: Poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis, autoimmune (e.g. lupus), IgA nephropathy

- Anti-GBM deposition: anti-glomerular basement membrane disease

- Small-vessel vasculitis: eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyangiitis, polyangiitis with granulomatosis

For more information see our note on Nephritic syndrome.

Diagnosis & investigations

The principal investigation for a suspected glomerular disease is a renal biopsy.

The clinical presentation, pattern of renal injury (i.e. nephritic versus nephrotic), and serological markers (e.g. specific antibodies) can all be used to help determine the underlying diagnosis alongside the results of a renal biopsy.

Urinary tests

Basic urinary tests are important to provide objective measurement of blood and/or protein in the urine

- Urine dipstick: most sensitive for detection of albumin

- Urinary protein:creatine ratio: a spot sample is collected to determine the protein content (level of protein divided by level of creatinine). Normal is < 30 mg/mmol

- 24 hour urinary collection: urine is collected over 24 hours to determine the protein content. Normal is < 0.2 g

Blood tests

A series of basic blood tests are required in any patient with suspected glomerular disease.

- Full blood count

- Urea & electrolytes

- Bone profile

- HbA1c

- Blood gas

- Lipid profile: hyperlipidaemia seen in nephrotic syndrome

Renal screen

This refers to a series of specialist blood tests that are completed to look for the possible causes of acute renal impairment and glomerular disease. It is a broad screen that can test for specific causes of glomerular disease, or at least provide important clues to the possible underlying cause.

- Complement: typically low in vasculitis

- Anti-nuclear antibody (ANA)

- Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)

- Anti-glomerular basement membrane antibody (GBM)

- Anti-dsDNA: raised in systemic lupus erythematosus

- Myeloma screen: serum free lights chains, protein electrophoresis

- Anti-PLA2R autoantibody: raised in membranous nephropathy

- Virology: Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C and Human immunodeficiency virus

- Cryoglobulins: immunoglobulins that precipitate at low temperatures

- Creatine kinase: may be raised in rhabdomyolysis

Imaging

Imaging using a renal ultrasound or CT kidney, urinary, and bladder (CT KUB) is essential in the work up of acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease to exclude an obstructive pathology and assess the overall structure of the kidneys (e.g. any features of polycystic).

Renal biopsy

A renal biopsy is the principal investigation for the diagnosis of glomerular disease. It involves taking a sample of renal tissue through an US-guided percutaneous biopsy. The kidney tissue can then be looked at under the microscope and special stains applied to visualise the glomeruli and assess for typical patterns of disease. These patterns combined with the clinical history to help to confirm the diagnosis.

In certain cases, a biopsy cannot be performed because there is an absolute or relative contraindication or the diagnosis is secure based on the clinical information (e.g. serological diagnosis) or the presentation is stereotypical (e.g. nephrotic syndrome in children – most likely minimal change disease).

Management

Management of glomerular disease should be directed towards the underlying cause.

The management of any glomerular disease depends on the underlying cause, which is why making a formal diagnosis is extremely important.

The management of individual conditions is beyond the scope of these notes, but we should consider some key management principles for all glomerular diseases that includes:

- Regular monitoring: rapid changes in renal function can occur with development of complications

- Treat underlying cause: specific therapies may be available for some conditions. For example, corticosteroids are used in minimal change disease and potent immunosuppressive drugs may be utilised in ANCA-associated vasculitis

- Determine natural history: for example, poststreptococcal glomerulonephropathy has a good prognosis with only supportive treatment whereas anti-GBM disease is associated with rapid development of end-stage renal disease untreated

- Treat complications: nephrotic syndrome is associated with hyperlipidaemia and thrombotic complications that needs addressing. Causes of nephritic syndrome may have extra-renal manifestations (e.g. pulmonary haemorrhage) that require urgent management.

- Consider renal replacement therapy: early involvement of the renal physicians and/or intensive care team is vital in cases of severe AKI. It can lead to life-threatening complications including hyperkalaemia, fluid overload, acidosis and uraemia.