Overview

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is generally defined as a sudden decline in renal function over hours or days.

AKI is a common medical condition affecting up to 15% of emergency hospital admissions and the mortality associated with severe AKI can be up to 30-40%. A decline in renal function can lead to dysregulation of fluid balance, acid-base homeostasis and electrolytes.

AKI has largely replaced the term ‘acute renal failure’. This change in nomenclature reflects the significance that small decrements in renal function do not lead to overt renal failure, but do have a clinical impact on morbidity and mortality.

Classification

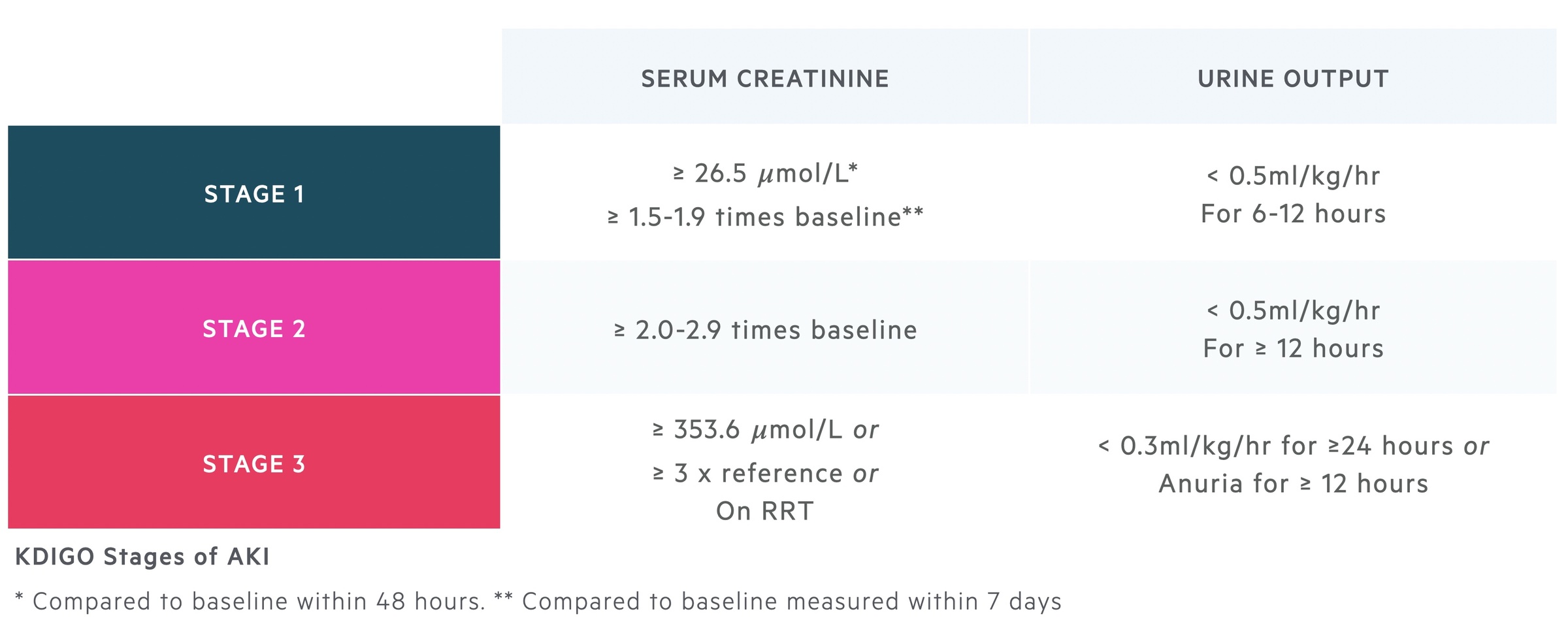

AKI may be classified by a number of systems including RIFLE and KDIGO.

A number of different staging systems have been proposed to help grade the severity of AKI including the ‘RIFLE’ criteria, ‘AKIN’ criteria and more recently the ‘Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes’ (KDIGO) criteria.

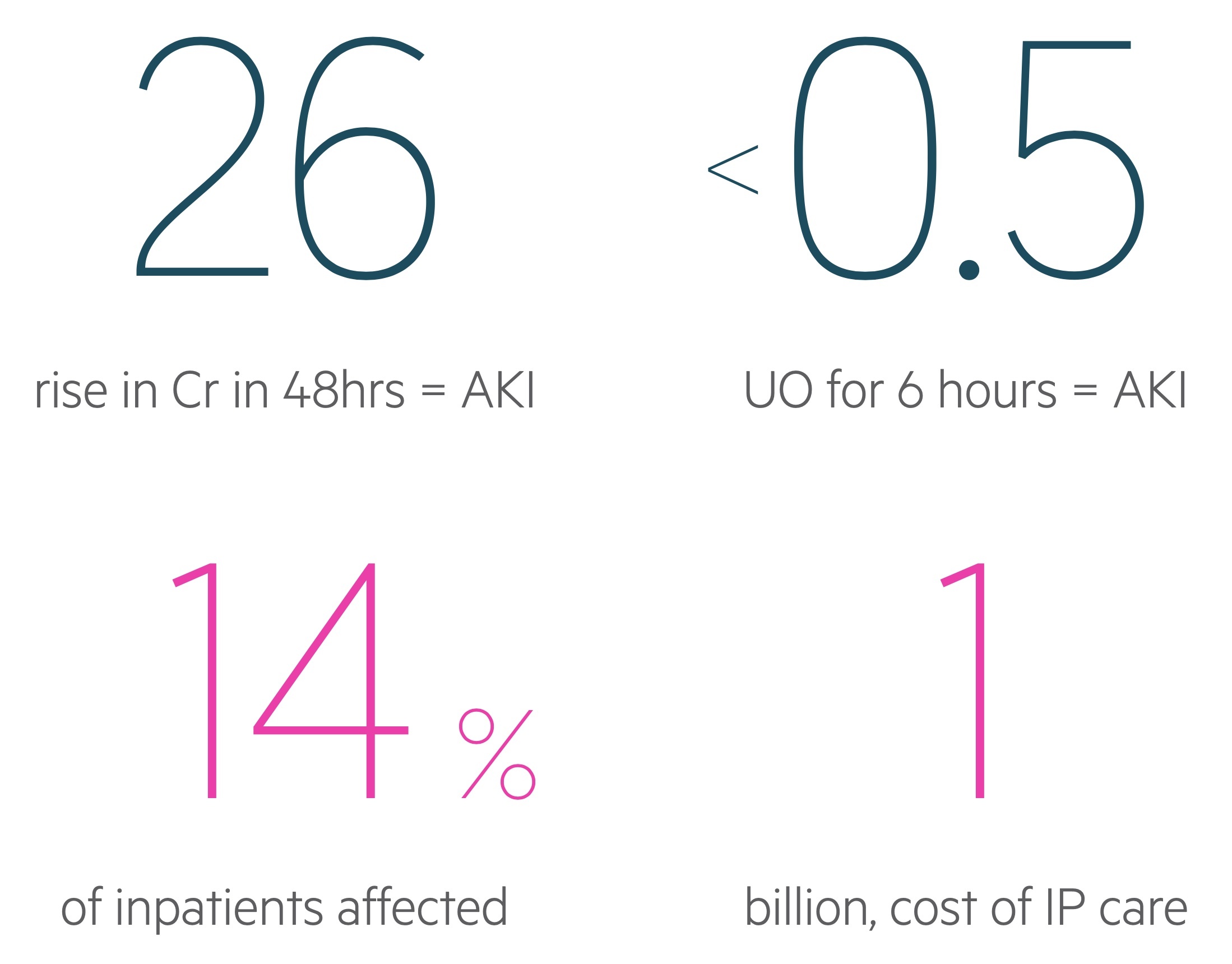

Based on the KDIGO criteria, an AKI is defined by one of the following parameters:

- An increase in serum creatinine by ≥ 26.5 micromol/L within 48 hours

- An increase in serum creatinine to ≥ 1.5 times baseline within 7 days

- Urine output < 0.5 mL/kg/hr for six hours

The KDIGO criteria divide AKI into three stages.

Aetiology

The aetiology of AKI can be categorised into pre-renal, intrinsic renal and post-renal causes.

1. Pre-renal

AKI is most commonly pre-renal in nature, typically occuring secondary to renal hypoperfusion.

Decreased renal perfusion can be related to reduced circulating volume (e.g. hypovolaemia), reduced cardiac output (e.g. cardiac failure), systemic vasodilatation (e.g. sepsis) or arteriolar changes (e.g. secondary to ACE-inhibitor or NSAID use).

Renal hypoperfusion causes ischaemia of the renal parenchyma. Prolonged ischaemia can lead to intrinsic damage and the development of acute tubular necrosis (ATN). ATN is the most common cause of intrinsic renal AKI.

2. Intrinsic renal

The hallmark of intrinsic renal AKI is structural damage. It may be categorised according to the location of the pathology:

- Vasculature

- Glomerular

- Tubulointerstitial

Vascular

Large vessels are typically affected by atherosclerotic disease, thromboembolic disease and dissections (e.g. aortic). Other important causes include renal artery abnormalities such as renal artery stenosis and renal artery thrombosis.

Small vessel disease can occur secondary to vasculitides (these typically lead to the development of glomerular disease), thromboembolic disease, microangiopathic haemolytic anaemias (e.g. disseminated intravascular coagulation) and malignant hypertension.

Glomerular

Glomerular pathology can be divided into primary (not associated with systemic disease) and secondary (associated with systemic disease) causes. Glomerular pathology can lead to a number of classical acute presentations (e.g. nephritic/nephrotic syndrome). They are also a major cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Tubulointerstitial

Tubulointerstitial pathology causes damage to the renal parenchyma that can lead to scarring and fibrosis in the long-term. The most common tubulointerstitial cause of AKI is ATN, this frequently occurs secondary to prolonged renal hypoperfusion. Other tubulointerstitial causes include acute interstitial nephritis that can occur secondary to medications (e.g. NSAIDs, PPI’s, penicillins) and infections.

3. Post-renal

AKI secondary to post-renal causes result from obstruction (often referred to as obstructive uropathy) and accounts for up to 10% of cases.

Obstruction to urinary flow can occur anywhere along the urinary tract from renal pelvis to urethra. Common causes of obstructive uropathy include urinary stones (urolithiasis), malignancy (inc. intraluminal, intramural and extramural tumours), strictures and bladder neck obstruction (e.g. benign prostatic hyperplasia).

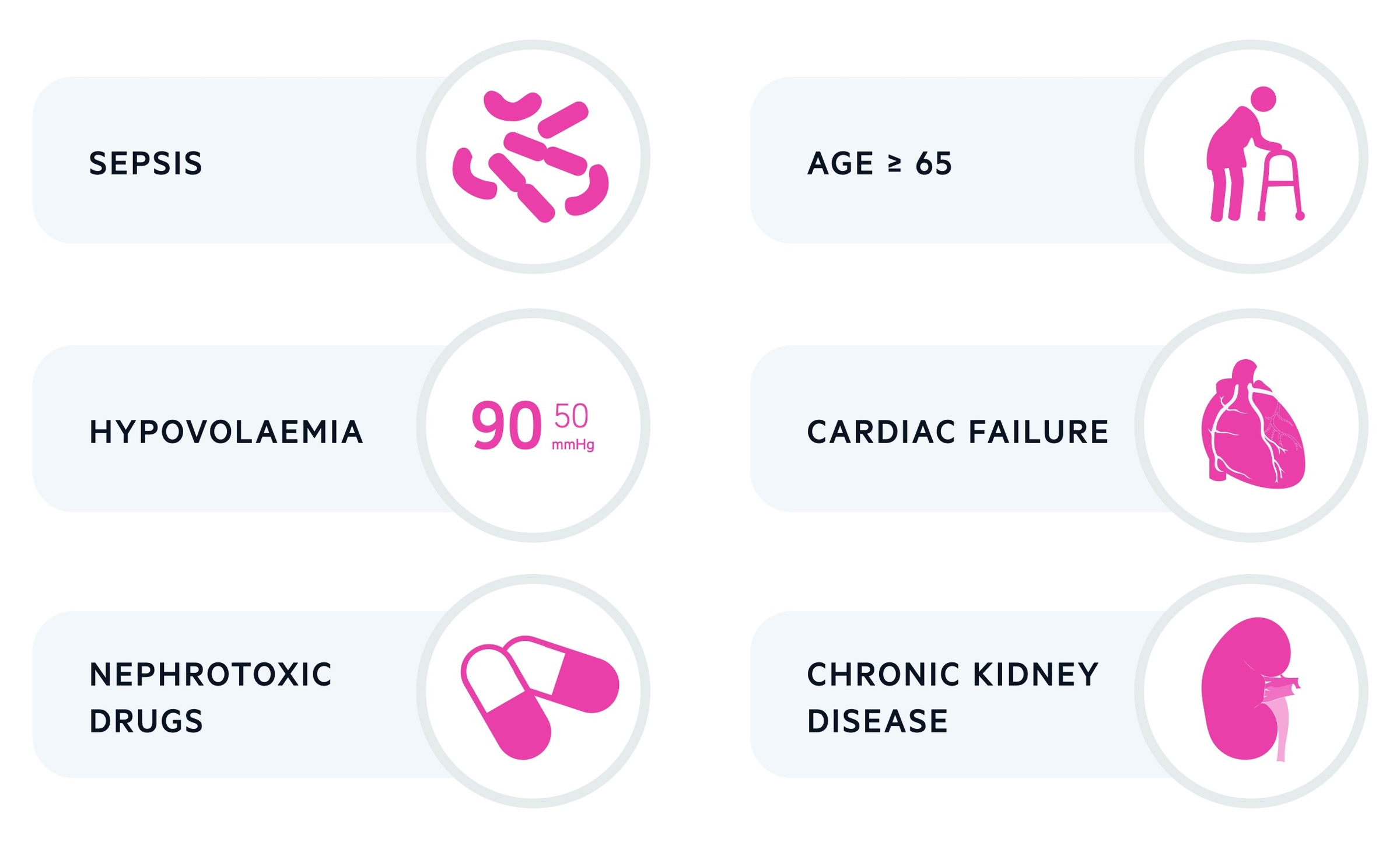

Risk factors

There are a number of risk factors that increase the likelihood of developing an AKI during hospital admission.

- Age (> 65 years old)

- History of AKI

- CKD

- Urological history (e.g. stones)

- Cardiac failure

- Diabetes mellitus

- Sepsis

- Hypovolaemia

- Nephrotoxic drug use

- Contrast agents

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of AKI is largely dependent on the underlying cause.

A common link between the aetiology of AKI is a reduction in the glomerular filtration rate (GFR), which may occur secondary to hypoperfusion (pre-renal), renal parenchymal damage (intrinsic renal) or obstruction to urinary flow (post-renal). Here we will discuss acute tubular necrosis (ATN) a common pathway of injury in a number of causes of acute kidney injury.

ATN can be divided into three stages:

- Initiation: acute decrease in renal perfusion causing a reduced GFR

- Maintenance: GFR remains low for days or weeks

- Recovery: GFR recovers, regeneration of tubulointerstitial cells, polyuric phase may occur

Acute tubular necrosis (ATN) has many causes, most of which can be thought as ‘ischaemic’ or ‘nephrotoxic’ in nature. Ischaemic causes are those of pre-renal AKI described above. Nephrotoxic causes include medications (aminoglycosides, chemotherapies), contrast, myoglobin (in rhabdomyolysis) and multiple myeloma.

Failure of adequate renal perfusion results in ischaemia. Ongoing ischaemia causes a pro-inflammatory response with the release of cytokines, oxygen free radicals and activation of leucocytes and coagulation pathways. At this point, if renal perfusion is not restored, the ongoing ischaemia can lead to cellular injury.

Tubular cells are particularly susceptible due to their limited blood supply and high metabolic demand. Damaged tubular cells slough off into the lumen as obstructive casts that further hamper the GFR. Following restoration of a normal GFR the kidneys may recover and tubulointerstitial cells regenerate. A polyuric phase often occurs, this is thought to be due to failure of adequate reabsorption by the recovering tubules.

Clinical features

The clinical features associated with AKI are usually non-specific and related to the underlying diagnosis.

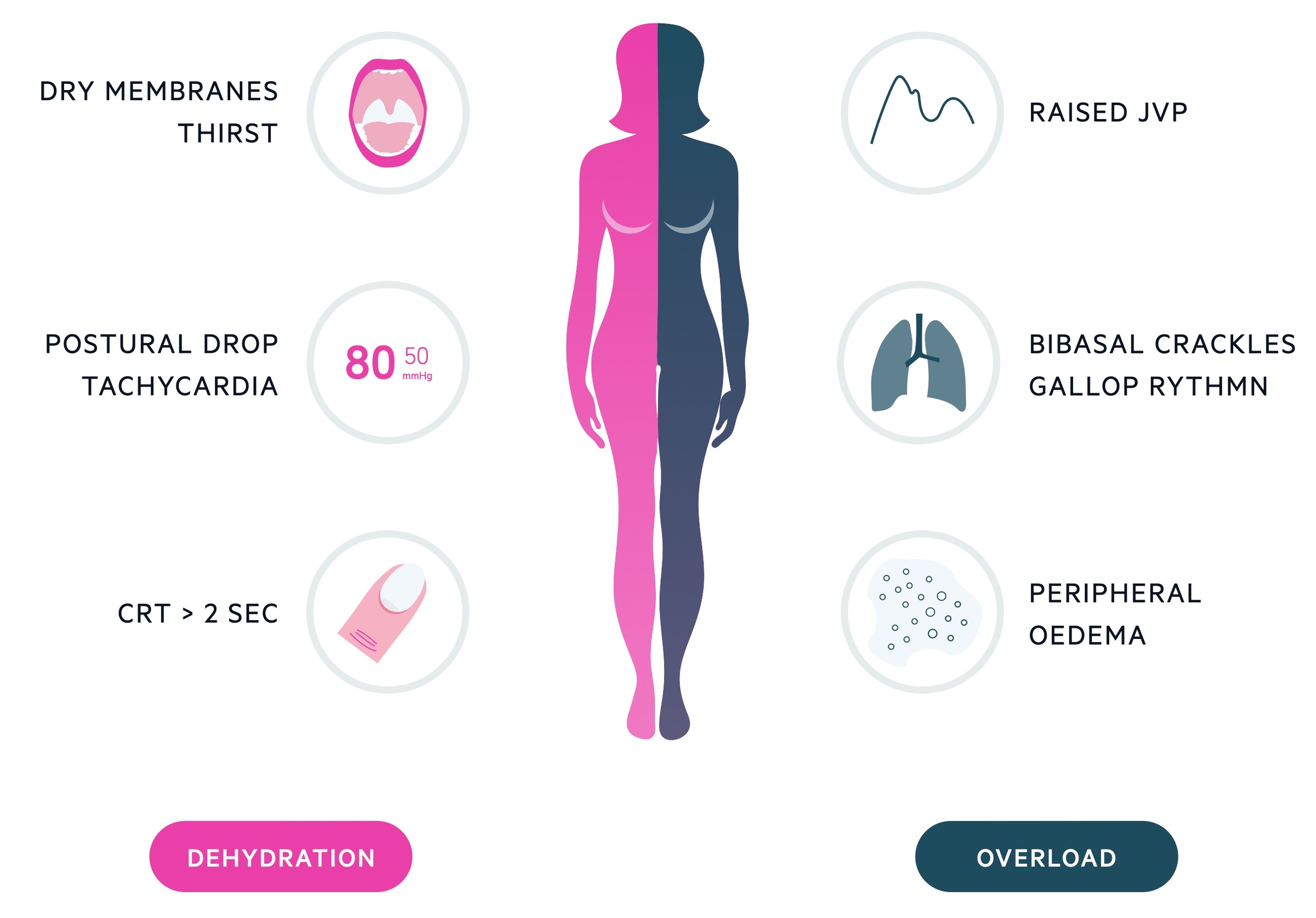

An accurate fluid balance assessment is key. The patient’s fluid balance is suggestive of the underlying aetiology of AKI and may guide subsequent management.

Pre-renal

Patients usually present with clinical features of hypovolaemia & dehydration.

- Reduced capillary refill time

- Dry mucous membranes

- Reduced skin turgor

- Thirst

- Dizziness

- Reduced urine output

- Orthostatic hypotension

It is important to consider features associated with fluid loss including excessive sweating, vomiting, diarrhoea and polyuria. In elderly patients, there may also be evidence of confusion.

In patients with renal hypoperfusion in the context of hypervolaemia (e.g. cardiac failure), it is important to assess for fluid overload.

- Ankle swelling

- Orthopnoea

- Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea

- Dyspnoea

- Raised JVP

- Ascites

Intrinsic renal

The clinical presentation of intrinsic renal AKI is dependent on the specific aetiology.

Patients with ATN will demonstrate features consistent with the underlying aetiology. Those with intrinsic glomerular pathology may present with features of nephritic syndrome (e.g. haematuria, proteinuria, oliguria and hypertension) or nephrotic syndrome (e.g. heavy proteinuria, hypoalbuminaemia and oedema).

Patients with a tubulointerstitial disease (e.g. acute interstitial nephritis) may complain of arthralgia, rashes and fever. Eosinophilia is frequently seen.

Post-renal

The clinical features of post-renal AKI depend on the site, chronicity and laterality (unilateral or bilateral) of the obstruction.

Patients with urinary stones may present with classical loin-to-groin pain, haematuria, nausea and vomiting. Those with prostatic problems may have lower urinary tract symptoms (e.g. dysuria, frequency, terminal dribbling, hesitancy). Obstruction at the bladder neck might be associated with a palpable bladder and a tender suprapubic area.

Investigations

The assessment and workup for a patient with AKI is important to determine the underlying cause and help guide further management.

Basic assessment

Assess the current fluid status of the patient, looking for signs of hypo- or hypervolaemia including checking their urine output. Review their medical chart looking for any potential nephrotoxic drugs and their fluid status over the last few days (e.g. have they had a positive or negative fluid balance).

Bedside

- Urine dipstick

- Urine microscopy

- Urine osmolality and electrolytes

- ECG

Bloods

Basic blood tests should include an FBC, U&Es, bone profile and blood gas (venous/arterial). This allows a quick assessment of the extent of renal injury and the development of any potential complications like hyperkalaemia or metabolic acidosis.

Other bloods can be completed depending on the suspected cause of AKI. Many of these look for intrinsic renal causes of AKI.

- Creatine kinase

- Vasculitis screen (e.g. ANCA, ANA)

- Clotting

- Blood film

- Complement

- Immunoglobulins

- Serum electrophoresis

- Virology (hepatitis B/C)

Imaging

The key radiological investigation in the assessment of AKI is ultrasound, which can look for evidence of obstructive uropathy (e.g. hydronephrosis). If there is a high degree of suspicion of urinary stones, a non-contrast CT may be completed.

Other radiological investigations may include:

- CXR (eg. looking for signs of overload)

- Renal dopplers (renal vascular assessment)

- Magnetic resonance angiography (renal vascular assessment)

Management

The management of an AKI should involve regular assessment and monitoring, controlling volume dysregulation and correcting electrolyte abnormalities and metabolic acidosis.

Principles of management

Management is guided by the underlying cause. Here we will discuss the general principles of management that can be applied to most cases of AKI.

Patients can be staged according to the KDIGO criteria. It is suggested that patients who have stage 3 AKI or a suspected diagnosis that may require specialist intervention (e.g. glomerulonephritis, systemic vasculitis), be discussed with a nephrologist within 48 hours of detection. Patients with post-renal AKI may require discussion with a urologist.

Regular assessment and monitoring

Regular assessment of the patients’ fluid status should be completed including monitoring their urine output, which may require a urinary catheter and daily weights.

A baseline creatinine should be recorded and serial U&Es taken daily, increased to twice daily in more severe cases.

Nephrotoxic drugs should be stopped (e.g. ACEi, NSAIDs, spironolactone) and regular prescriptions should be altered to reflect the change in creatinine clearance.

Volume dysregulation

If patients are hypovolaemic then intravenous fluids should be prescribed. The amount and type of fluids will depend on the clinical status of the patient.

If the patient is hypervolaemic they may require fluid restriction +/- the use of diuretics. Diuretics (e.g. furosemide) should be used carefully in renal impairment as they can be nephrotoxic.

Electrolyte abnormalities

Severe hyperkalaemia, variably defined as >6.5 or 7 mmol/L, is a medical emergency.

The management of hyperkalaemia is critical to avoid potential life-threatening arrhythmias. It involves:

- Protection of the myocardium: 10ml of 10% calcium gluconate.

- Reduce extracellular potassium: aim is to drive potassium into the intracellular compartment. Insulin (e.g 10 units ACTRAPID in 100ml 20% dextrose) and beta agonists (e.g. 2.5mg nebulised salbutamol) are given.

- Additional: stop or adjust potassium-sparing or potassium-containing medications. Resins can reduce potassium absorption but these take hours/days to have effect.

Other electrolyte problems include hypocalcaemia and hyperphosphataemia.

Metabolic acidosis

The handling of acid-base is impaired in the setting of AKI due to a reduction in the GFR. This can results in a metabolic acidosis. Depending on the severity of acidosis and associated clinical state, choices for management involve the use of sodium bicarbonate or dialysis.

Complications

The major complications that can occur in association with AKI include hyperkalaemia, fluid overload, metabolic acidosis and uraemia.

The development of uraemic complications (e.g. encephalopathy, pericarditis), hyperkalaemia, fluid overload or metabolic acidosis that are refractory to medical therapy warrant urgent dialysis.

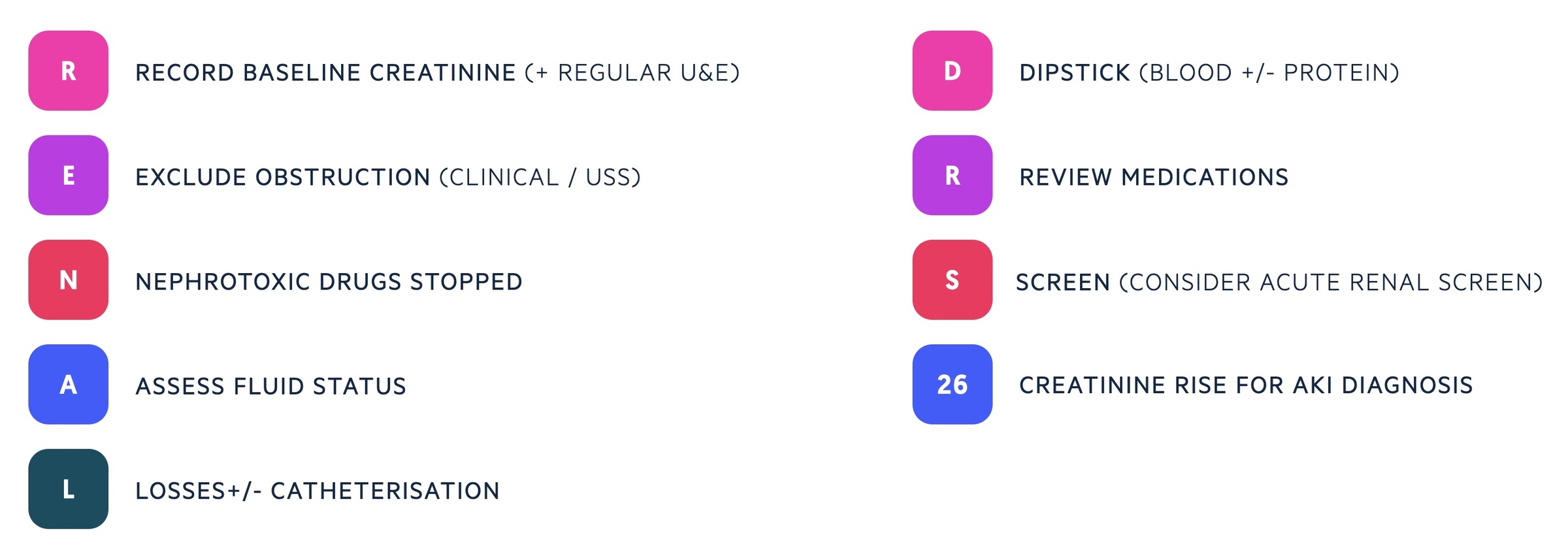

RENAL DRS 26

A useful mnemonic for assessment and management of any patient presenting with an acute kidney injury.