Definition

Malignant superior vena cava obstruction (SVCO) refers to an obstruction to the flow of blood through the superior vena cava (SVC) secondary to a cancer.

The SVC provides venous drainage for the upper limbs, head and neck. It originates posterior to the lower aspect of the right first costal cartilage at the union of the right and left brachiocephalic veins. It then descends to join the right atrium at the level of the right third costal cartilage. It is a valveless structure.

Aetiology & pathophysiology

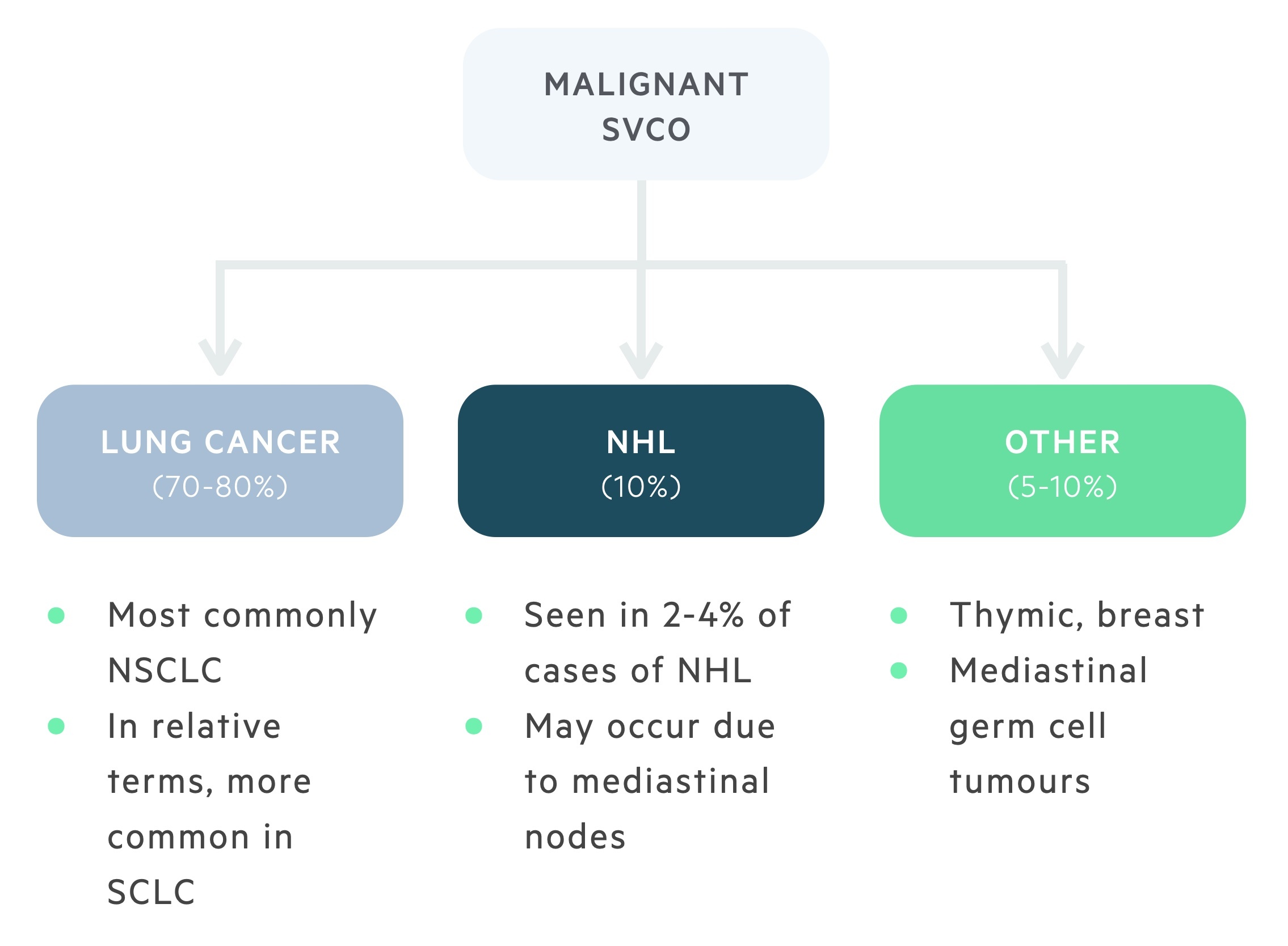

Malignancy accounts for 60-80% of cases of SVCO.

The aetiology of SVCO has changed over the years. Where once infections (e.g syphilis) were the most common cause, malignancy now predominates. Lung carcinoma and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) are most commonly identified.

Less common causes include thymic, breast and mediastinal germ cell tumours. SVCO may result from direct tumour growth or lymphadenopathy. It is estimated that 60% of patients presenting with malignant SVCO will have a previously undiagnosed malignancy.

Obstruction of the SVC results in the formation of collateral vessels. Four collateral systems exist, the azygous system, internal mammary and long thoracic system (femoral and vertebral).

Collaterals take time to develop, therefore clinical features are dependent on the time frame over which the obstruction develops. A slowly progressing obstruction allows time for adequate collateral formation and as such symptoms may be mild.

Lung cancer

Less than 2% of patients with non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) will develop SVCO. However, due to the high incidence of NSCLC, it accounts for 50% of all malignant cases of SVCO.

Due to their central location and rapid growth, the incidence of SVCO in small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) is greater than that of NSCLC at 10%, though SCLC itself is less common. SCLC is responsible for 25% of malignant cases of SVCO.

NHL

NHL accounts for up to 10% of cases of malignant SVCO. SVCO is seen in approximately 2-4% of NHLs. The overall prevalence of SVCO in NHL is dependent on the subtype, with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and lymphoblastic lymphomas the most frequent causes.

Clinical features

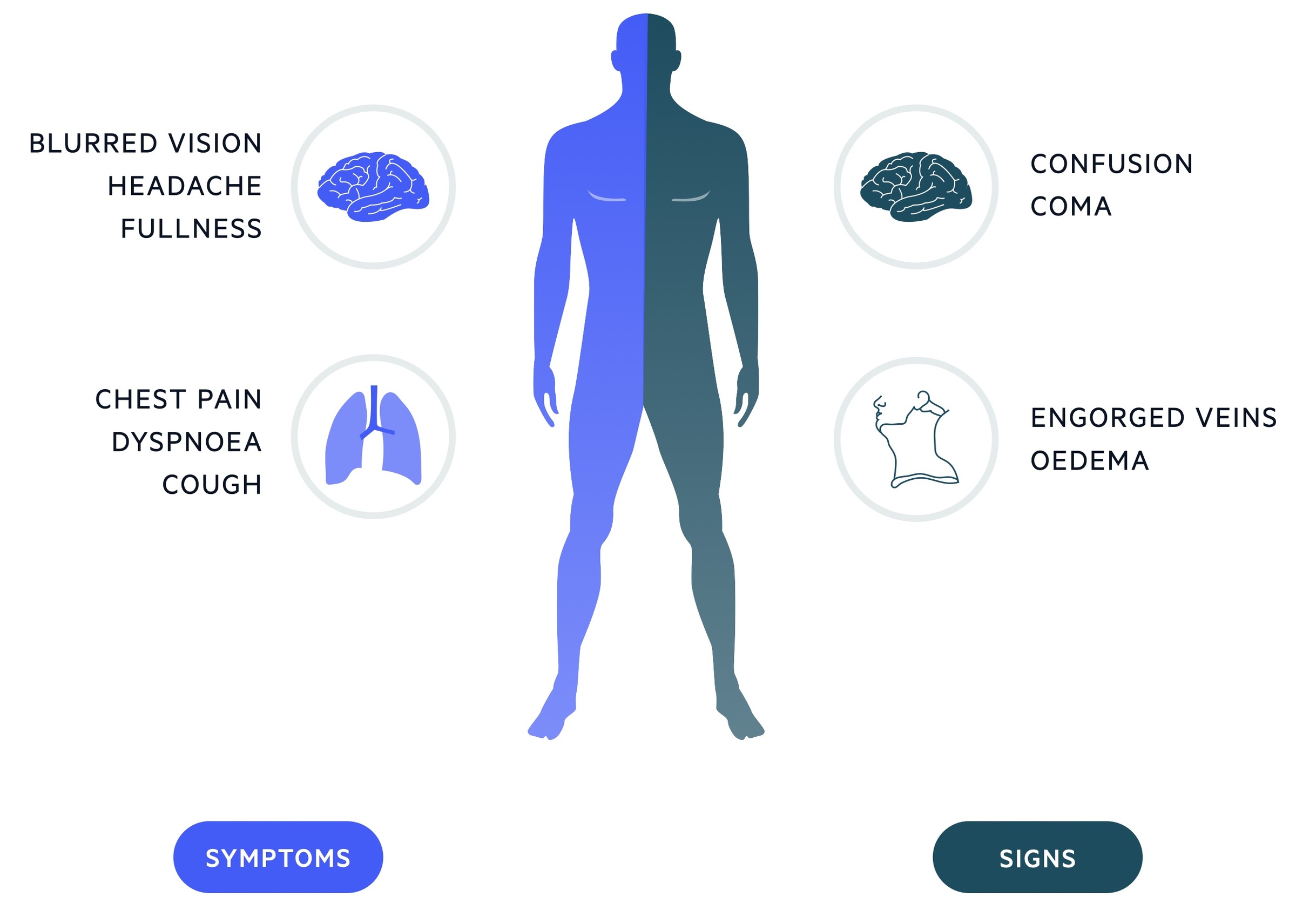

SVCO presents with dyspnoea, facial swelling, head fullness and cough.

It is important to recognise patients requiring urgent management. Any patient with signs of airway obstruction (stridor may be present) or neurological symptoms consistent with cerebral oedema require urgent senior review or MET/Peri-arrest call as appropriate.

Symptoms

- Dyspnoea

- Facial swelling

- Head ‘fullness’

- Symptoms exacerbated by bending forwards / lying down

- Cough

- Dysphagia

Signs

- Facial swelling

- Distended neck and chest wall veins

- Upper limb oedema

- Facial plethora

- Cyanosis

- Cognitive dysfunction

- Coma

Pemberton’s sign

To elicit this sign the patient is asked to elevate both arms above the head for 1-2 minutes. It is considered positive if it causes congestion, cyanosis or respiratory distress. This occurs due to increased venous return from the upper extremities exacerbating any obstruction.

Investigations & diagnosis

80% of patients with SVCO have an abnormal chest radiograph.

Imaging is key to diagnosing SVCO. Investigations are targeted at identifying SVCO and revealing its underlying cause. Imaging may be both diagnostic and prognostic (tumour staging).

Radiological diagnosis

A chest radiograph is the most appropriate initial investigation and helps exclude other causes of breathlessness. Upwards of 80% of patients with malignant SVCO will have an abnormality identifiable on chest radiograph. Findings include mediastinal widening and (malignant) pleural effusion.

A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the chest is diagnostic. It reveals the extent and level of obstruction, the presence of collateral vessel formation and the likely underlying cause. A CT scan is a staging investigation for lung cancers. A PET CT, CT abdomen/pelvis and MRI brain may be required to complete staging (to identify metastasis).

Duplex ultrasound may be used to identify SVCO, it is frequently used in patients with indwelling catheters. MRI and contrast venography are rarely used.

Histological diagnosis

If a malignant cause is suspected then it is important that a tissue diagnosis is acquired. This may involve minimally invasive procedures (e.g. sputum/pleural fluid cytology, lymph node biopsy, bone marrow biopsies) or invasive procedures (e.g. bronchoscopy, mediastinoscopy, video-assisted thoracoscopy).

Emergency management

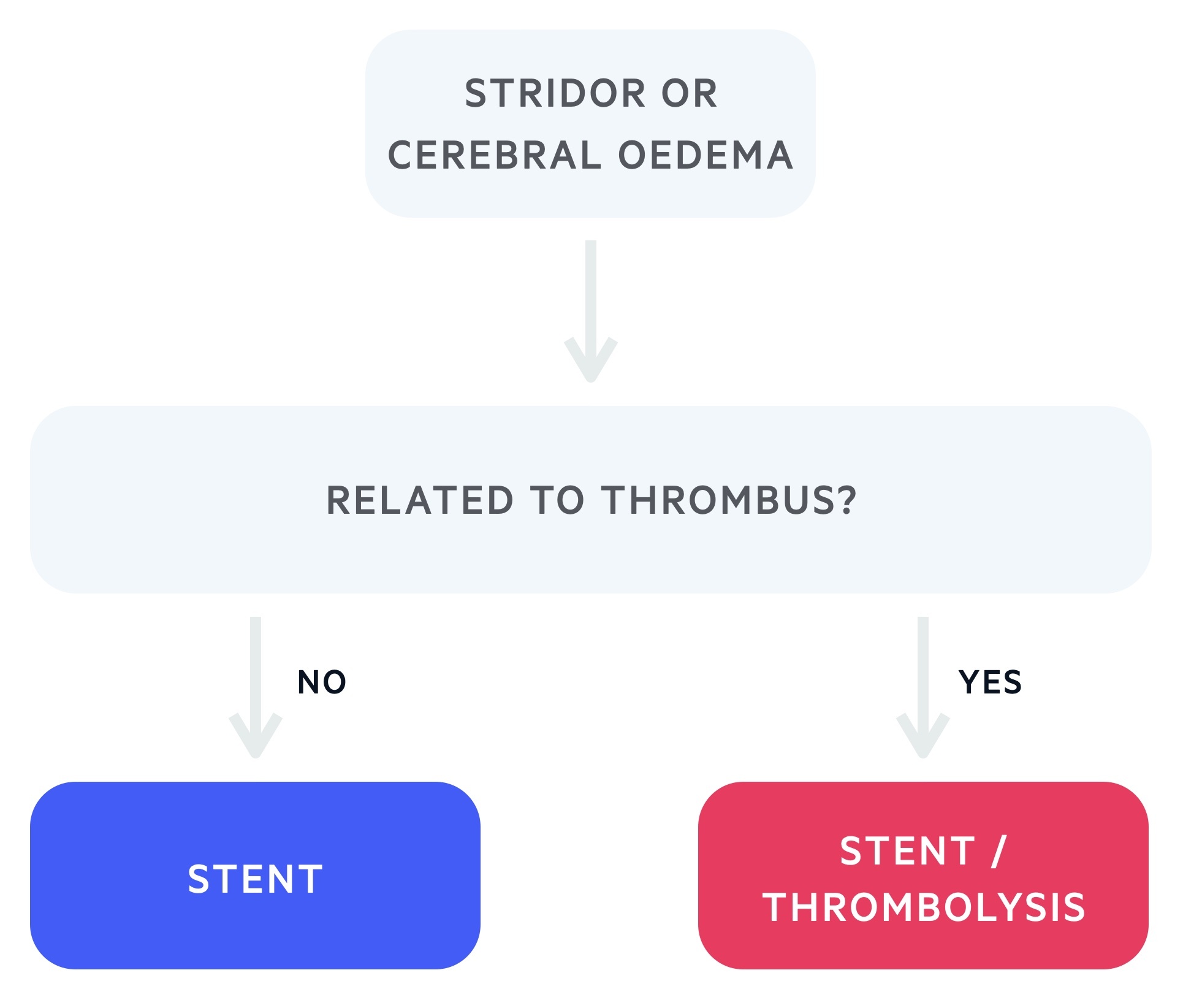

In rare cases SVCO requires emergency management to treat respiratory distress or cerebral oedema.

Though uncommon, SVCO can represent a medical emergency. Any patient with signs of airway obstruction (stridor may be present) or neurological symptoms consistent with cerebral oedema require urgent senior review or MET/Peri-arrest call as appropriate.

Medical therapies such as diuretics and steroid should be considered. Definitive management with an endovascular stent, shunt or thrombolysis may be indicated.

General management

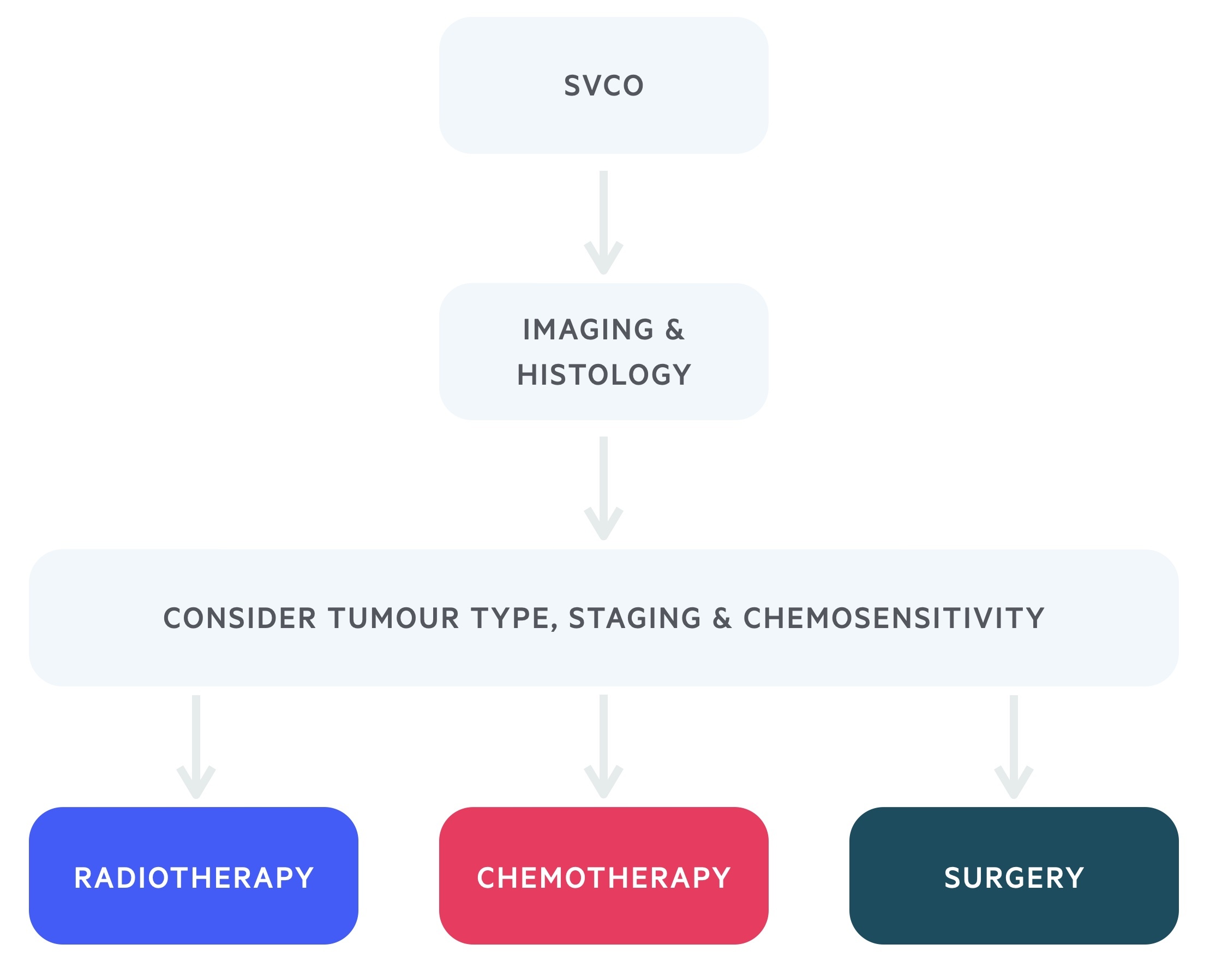

Management of SVCO involves relieving the obstruction and treatment of the underlying cause.

The majority of patients present in a subacute manner, not necessitating emergency management. Conservative measures should be implemented, these include elevation of the head and neck and oxygen titrated to saturations. Typically there is time to obtain a histological diagnosis prior to the initiation of treatment.

Stenting, radiotherapy and chemotherapy are the mainstays of treatment. Although evidence is scarce, glucocorticoids may be used to help reduce swelling and improve symptoms in acute obstruction, especially with steroid-responsive tumours (e.g. lymphoma). Dexamethasone is the glucocorticoid of choice in this setting.

Medical therapy

Many tumours causing SVCO are radiosensitive. Radiotherapy is highly effective and as such is often the first line therapy in patients with NSCLC and lymphomas.

Chemotherapy may be used in chemosensitive tumours such as SCLC and NHL. Anticoagulation or thrombolysis may be used if SVCO occurs secondary to intravascular thrombosis.

Surgical therapy

The placement of an endovenous stent has a technical success rate of 95-100% and is able to restore venous return with relief of symptoms in up to 90% of patients. Both balloon expandable and self-expanding stents can be used. They are placed percutaneously with access via the internal jugular, basilic or femoral veins under local anaesthetic.

Recurrence of SVCO may occur, but this is usually amenable to reintervention or thrombolytic therapy. Complications are seen in 3-7 % of patients treated with a stent, including infection, pulmonary embolus, stent migration, and rarely perforation of the SVC.

Prognosis

Patients presenting with malignant SVCO have an average life expectancy of six months.

Prognosis of relief from SVCO itself is good. Management of SVCO is effective with the use of endovenous stenting, radiotherapy and treatment of the underlying malignancy.

Malignant SVCO is a negative prognostic indicator in terms of cancer survival. This reflects the extent of tumour or lymphadenopathy necessary to develop obstruction of the superior vena cava.