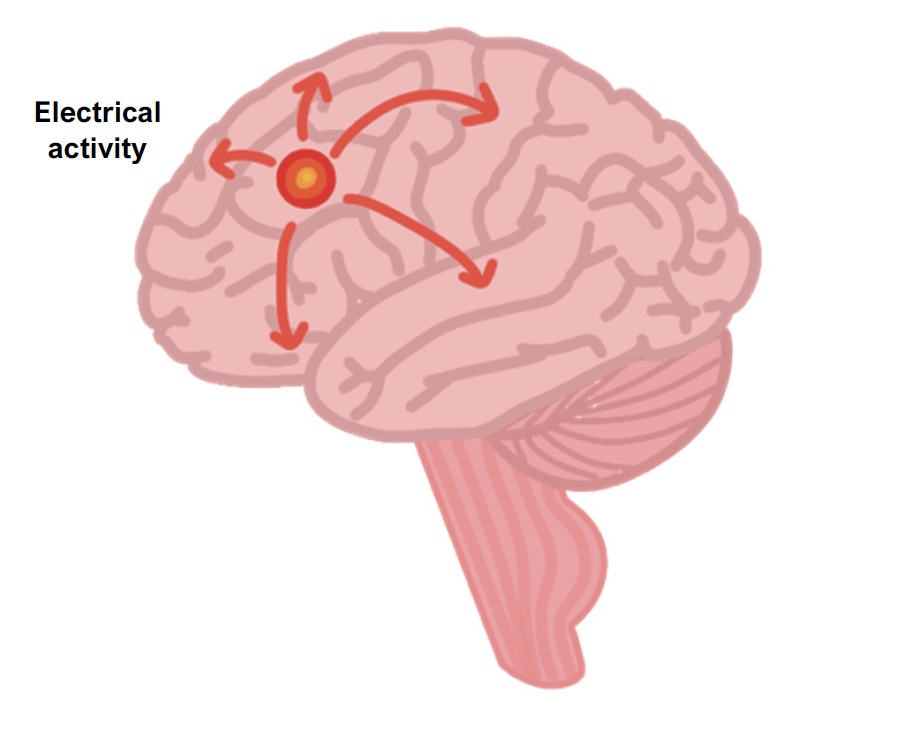

This term describes a tendency to have seizures: these are episodes of sudden and abnormal electrical activity in the brain.

Convulsions are motor signs of the electrical discharges.

Seizures are often preceded by a prodrome – this may last for hours and are characterised by a change in mood/behaviour or a nonspecific “funny feeling.”

Seizures are usually stereotypical, i.e., same aura and ictal features

An aura occurs just prior to the seizure and may include a feeling of d.j. vu, sensory hallucinations, emotional feelings, limb sensations or visual disturbances.

Post-ictally, patients can experience headache, fatigue, confusion, myalgia and weakness lasting for 15 minutes up to several hours.

Causes

The majority of cases are idiopathic

Genetic causes

Trauma, stroke, cancer, infection

Metabolic (e.g., hypoglycaemia)

Alcohol (intoxication and withdrawal)

Electrolyte disturbances

Focal seizures

This describes a seizure that originates within one part of the brain.

They are subdivided into focal aware (these occur without impairment of consciousness) and focal with impaired awareness.

You can also get focal to bilateral tonic-clonic seizures, where the electrical disturbance starts focally, then becomes generalised.

Symptoms

Motor – automatisms, atonic, clonic, spasms, hyperkinetic, myoclonic tonic

Non-motor – autonomic, behaviour arrest, cognitive, emotional, sensory changes

Specific symptoms

Generalised seizures

These are characterised by widespread discharge, across both hemispheres, without warning. This often leads to a loss of consciousness and well as other symptoms.

Patients may also bite their tongue and become incontinent of urine.

We can subdivide these into those with motor and non-motor symptoms.

Motor

Tonic-clonic – involve tonic (stiffenng) and clonic (twitching/jerking) muscle activity

Myoclonic – single or series of muscle jerks of limb/face/trunk, may cause the patient to be thrown to the ground, known as a “drop attack.” This can cause a musculoskeletal injury (e.g., posterior displacement of the shoulder)

Atonic – sudden loss of muscle tone, can also cause “drop attacks”

Tonic – bilateral increased tone of the limbs

Non-motor

Absence – brief (< 10 s) pauses usually in childhood (4–8 years), without a history of convulsions. Patients can experience many per day.

Key tests

MRI – this identifies structural lesions

EEG – assesses the electrical activity of the brain and can be used to localise the seizure. If no seizures occur, we can perform an EEG following sleep deprivation, hyperventilation and photic stimulation.

Blood tests and lumbar puncture may help exclude other causes of seizure, e.g., electrolyte abnormality, encephalitis and meningitis, eclampsia, hypoglycaemia

Management

Refer to neurology. Treatment is usually commenced after the second seizure

Anti-epileptic medications should be as monotherapies and uptitrated to the maximum tolerated dose before the trial of a different monotherapy

Focal seizures – carbamazepine or lamotrigine are usually first-line

Generalised – lamotrigine, levetiracetam or sodium valproate (not to be used in women of childbearing age)

Absence seizure – sodium valproate or ethosuximide is first-line

Driving rules

Status epilepticus

This is the term which describes an acute seizure which persists > 5 minutes.

It is an emergency and has a high-risk of airway compromise.

Management

In the first 5 minutes, use ABCDE approach and get IV access

After 5 minutes, give IV lorazepam

If no IV access, then give buccal midazolam or rectal diazepam

If does not stop in 10 minutes, give IV phenytoin, sodium valproate or levetiracetam

If no response 30 minutes after onset, induce with general anaesthesia