Overview

Sepsis is a dysregulated host response to infection leading to life-threatening organ dysfunction.

Sepsis is a commonly encountered problem in the healthcare setting and a major cause of morbidity and mortality. In its most simplistic form, sepsis is organ dysfunction secondary to an infection. It is regarded as a dysregulated host response to infection that is associated with both clinical and biochemical abnormalities.

It can be difficult to understand sepsis because the terminology used to define the condition has changed over the years and there is no universal agreement. In addition, in clinical practice, we see organ dysfunction in many systemic diseases. This means it may be difficult to truly say the organ dysfunction is secondary to an infection, especially if a specific organism is not identified that is not uncommon.

In practice, if we suspect an underlying infection and we identify clinical and biochemical abnormalities consistent with organ dysfunction, we can define sepsis. Several scoring systems are available to help us make this diagnosis. Sepsis is most commonly attributable to bacterial infections and treatment centres on prompt recognition and administration of intravenous antibiotics.

Definitions

Several important definitions are used to define sepsis and the association severity.

The definition of sepsis has changed over the years and there is no universal agreement. Sepsis represents a continuous spectrum of severity from early infection to life-threatening organ dysfunction.

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome

Traditionally, sepsis was defined using the ‘systemic inflammatory response syndrome’ (SIRS) criteria. SIRS is essentially a clinical syndrome due to dysregulated inflammation that is defined by the presence of ≥2 of the following:

- Temperature: > 38.0º or < 36.0º

- Heart rate: > 90/min

- Respiratory rate: > 20/min

- White cell count: > 12 x109/L or < 4 x109/L

The presence of SIRS and a suspected or identified source of infection was originally used to define sepsis. This has fallen out of favour in recent years because SIRS may be caused by a whole number of conditions (e.g. autoimmune disease, pancreatitis, burns, vasculitis, etc) and not just infection.

Early sepsis

Sepsis lies on a spectrum of severity from simple infection and bacteraemia (i.e. evidence of infection without organ dysfunction) to severe multi-organ failure.

The early recognition and treatment of sepsis can be life-saving. This is why there has been significant emphasis on the recognition of sepsis in clinical practice. Several scoring systems can be used to try and detect early signs of sepsis. These include:

- qSOFA (quick Sepsis Related Failure Assessment): aims to identify patients at increased risk of poor outcomes outside the ITU environment. It consists of three components:

- Mental status (score 1 if altered mental status)

- Respiratory rate (score 1 if ≥ 22)

- Systolic BP (score 1 if ≤ 100)

- NEWS (National Early Warning Score): a score derived from a patients’ observations (RR, O2 sats, HR, BP, GCS, Temperature) that alerts healthcare staff to early deterioration that warrants a review.

Sepsis

The modern definition of sepsis has been determined by the 2016 Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) task force. They define sepsis as:

“Life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection”

Organ dysfunction is defined as an increase of ≥2 points in the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) Score. The SOFA score is an intensive care unit (ICU) tool that helps to predict mortality based on clinical and biochemical data. It is well-validated for use in sepsis.

There are several domains contributing to the score that each reflects an organ dysfunction:

- Respiratory dysfunction: Pa02, Fi02, need for ventilation

- Cardiovascular dysfunction: Blood pressure, need for inotropes

- Renal dysfunction: Acute kidney injury

- Haematological dysfunction: Platelet count, coagulation

- Liver dysfunction: Bilirubin

- Neurological dysfunction: Glasgow coma score

An infection should be suspected based on the presence of clinical features (e.g. productive cough, dysuria) and supporting evidence for infection based on microbiological and radiological data (e.g. culture results, CT showing a collection).

Septic shock

Shock describes circulatory failure resulting in inadequate tissue perfusion and insufficient delivery of oxygen. When this is secondary to sepsis we term it ‘septic shock’. This is a type of distributive shock because it is caused by peripheral vasodilatation leading to abnormal volume distribution and inadequate perfusion.

In relatively simple terms, septic shock is the presence of sepsis with hypotension (mean arterial pressure < 65 mmHg) despite adequate fluid resuscitation.

Patients with septic shock commonly require ICU support and inotropes (medicines that change the force of the hearts contraction and cause blood vessel vasoconstriction) to maintain adequate blood pressure.

Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome

The most severe end of sepsis is the development of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS). This refers to progressive organ dysfunction whereby homeostasis cannot be maintained without intervention. MODS is commonly the result of sepsis but can also be caused by non-infectious aetiologies.

For more information see our Multi-organ dysfunction syndrome note.

Aetiology

Sepsis is most commonly caused by bacterial infections.

A variety of infectious agents can lead to sepsis of which bacteria are the most commonly implicated.

- Bacteria (e.g. Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Escherichia)

- Viruses (e.g. Influenza, Coronavirus, Respiratory syncytial virus)

- Fungi (e.g. Candida, Aspergillus).

Importantly, in up to 50% of cases of sepsis, an organism cannot be identified.

Risk factors

There are several risk factors that increase the risk of sepsis. These include:

- Very young (<1 years old)

- Very old (>75 years old) or frail

- Immunosuppressed (use of chemotherapy, long-term steroids, transplant recipients, immunodeficiencies, immunosuppressive agents)

- Recent surgery (or invasive procedure)

- Intravenous drug misuse

- Indwelling lines (e.g. dialysis catheter)

- Breach of skin integrity (e.g. cuts, burns)

Pathophysiology

Sepsis is characterised by a dysregulated host immune response.

Sepsis is a complex process involving the infectious organism (i.e. the pathogen) and the host immune response to that pathogen. In general, the transition from infection to sepsis is usually marked by a release of many pro-inflammatory mediators (e.g. tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin (IL)-1β) that cause a systemic response leading to organ damage.

This systemic inflammatory response may be seen in the absence of infection, which is why there has been a move away from the traditional SIRS criteria for sepsis. There are many reasons why this systemic inflammatory response occurs including the virulence of the pathogen, excess production of proinflammatory cytokines at the initial site of infection, prominent activation of the complement system, and underlying genetic factors.

The consequence of this inflammatory response is cellular injury that occurs due to a variety of factors including tissue ischaemia, direct injury by pro-inflammatory mediators, and altered rates of apoptosis. Cellular injury culminates in organ dysfunction, which if severe, can lead to multi-organ dysfunction syndrome.

Clinical features

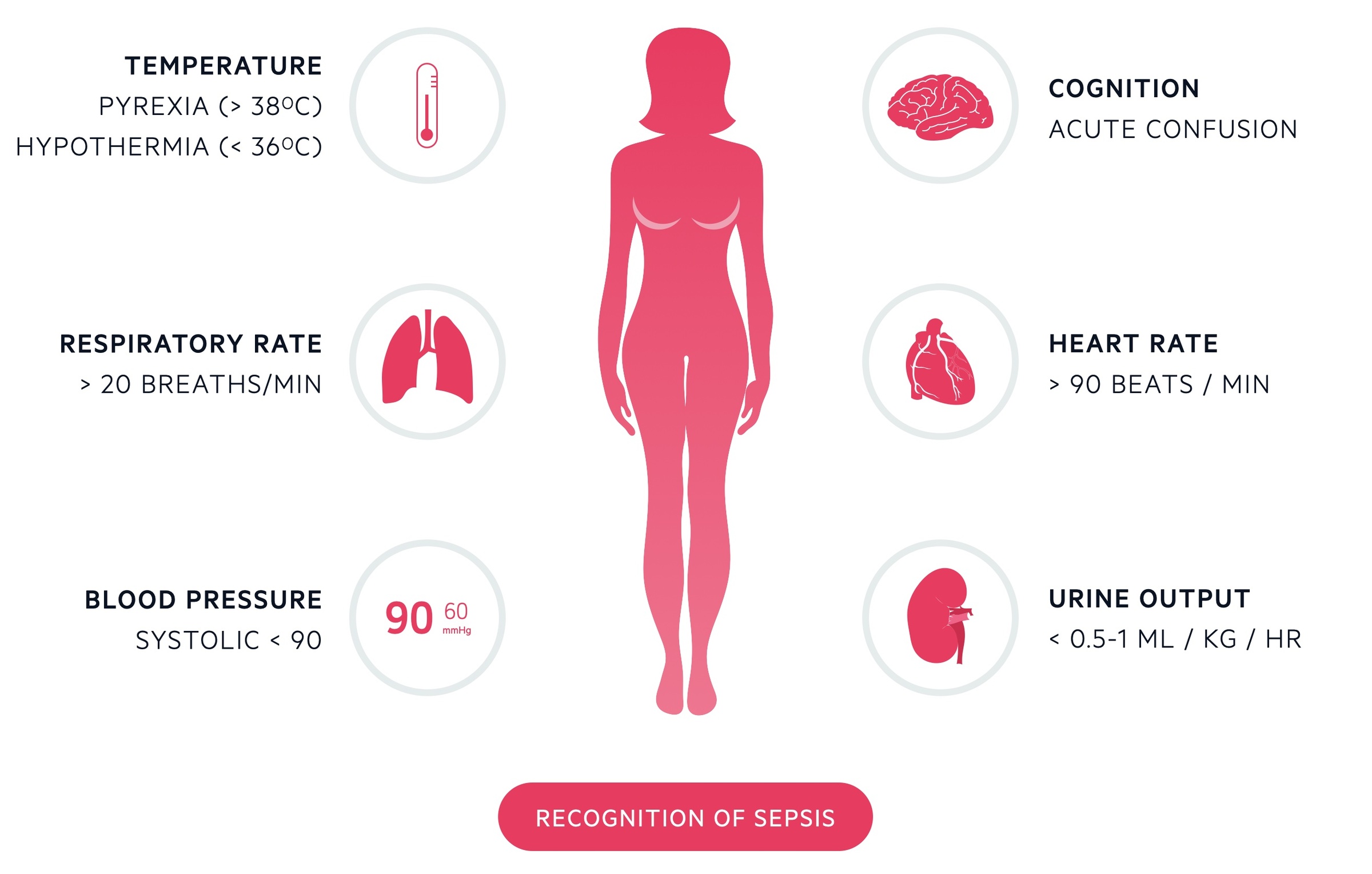

Classic features of sepsis include fever, tachycardia, tachypnea, and hypotension.

The clinical features of sepsis are often non-specific and may be attributable to other severe illnesses (e.g. pancreatitis).

Signs & symptoms

- Features of a specific infection (e.g. productive cough, dysuria, abscess, headache)

- Warm and flushed skin (vasodilatation due to inflammatory mediators)

- Cool, mottled skin (features suggestive of shock)

- Prolonged capillary refill time (features suggestive of shock)

- Febrile (>38.0º)

- Hypothermic (<36.0º)

- Tachycardia (>90)

- Tachypnea (>20)

- Hypotension (< 90 mmHg or decrease >40 mmHg)

Features of organ dysfunction

- Respiratory: hypoxia

- Cardiovascular: hypotension

- Gastrointestinal: jaundice, ileus (absent bowel sounds, distended abdomen, vomiting)

- Haematological: bleeding, bruising

- Neurological: altered mental status, agitated, reduced consciousness

- Renal: low urine output, anuric

Diagnosis

A prompt diagnosis of sepsis is usually made on early clinical suspicion.

A delay in the diagnosis of sepsis whilst awaiting investigations can lead to significant morbidity and mortality. Therefore, the diagnosis is usually made on clinical suspicion based on early observations and clinical assessment. Based on these data, treatment can be instigated.

A formal diagnosis may be made retrospectively based on the return of investigations (e.g. positive blood culture and evidence of acute kidney injury) in the context of the initial presentation (e.g. hypotension, altered mental status). In the absence of an identified pathogen, an improvement with antibiotics may indicate the cause of deterioration is an underlying infection. If there is no suggestion of an infection on subsequent investigations then treatment can be stepped down.

Any patient with suspected sepsis should have urgent observations and a clinical assessment. Features that suggest a high risk of severe illness or death from sepsis include:

- Heart rate: >130/min

- Respiratory rate: >25/min

- Blood pressure: <90 mmHg or >40 mmHg drop

- Level of consciousness: new altered consciousness

- Oxygen saturation: new need foo ≥40% oxygen to maintain sats >92% (88% for CO2 retainers)

- Urine output: <0.5 ml/kg/hour or not passed any for >18 hours

- Skin: mottled appearance, cyanosis, or non-blanching rash

NOTE: Do not use a person’s temperature as the sole predictor of sepsis and do not rely on fever or hypothermia to rule sepsis either in or out.

All patients with suspected sepsis should be urgently transferred to a hospital if they have high-risk criteria or they are < 17 years ago and their immunity is impaired by drugs or illness. Outside of the hospital setting, patients with moderate to high-risk criteria should be assessed to see whether they need treatment in a hospital.

Investigations & management

Investigations and management are completed concurrently in patients with suspected sepsis.

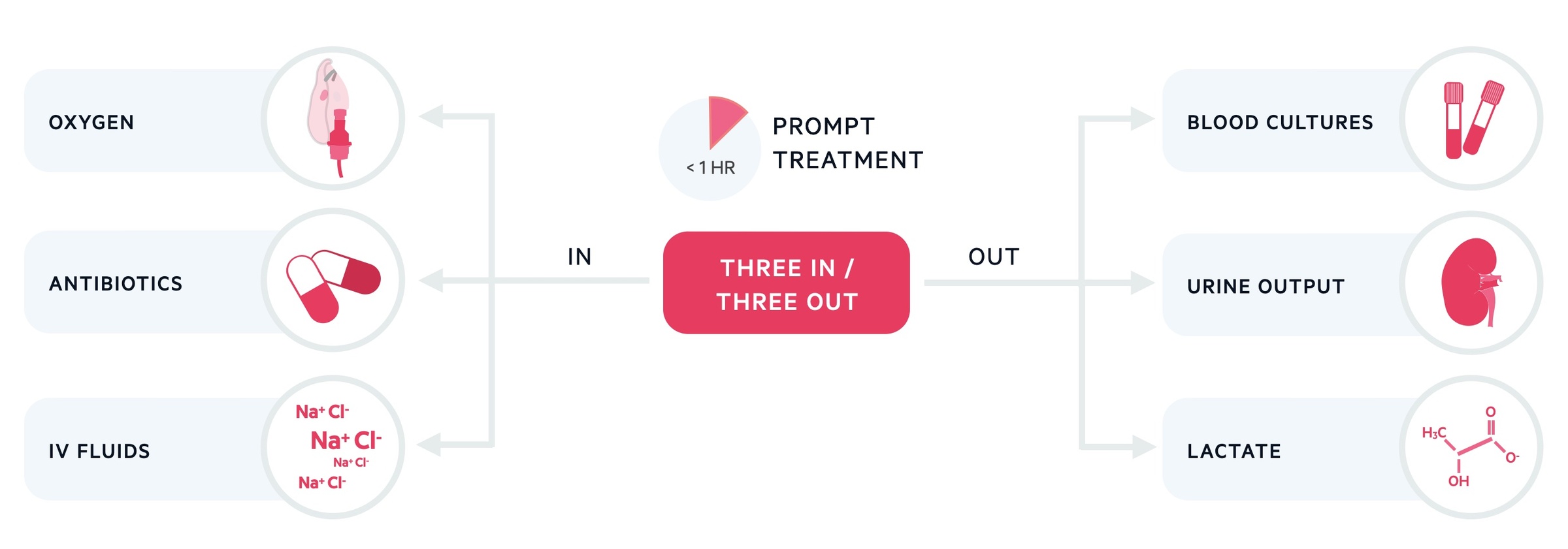

Any patient with suspected sepsis should be managed with the SEPSIS-6 principles in mind.

The sepsis six bundle is a protocol by which a patient may be investigated and treated for sepsis. It is by no means exhaustive but incorporates key investigation and treatment points. The bundle should be initiated and completed within one hour of recognition of the signs. All patients with a significant infection should have a senior review. Further support may be required including vasopressors (e.g. noradrenaline) to maintain blood pressure, given in A&E resus or ITU. The sepsis bundle can be remembered as ‘Three IN, Three OUT’.

Three In

Patients should receive high flow oxygen to achieve appropriate target saturations. A target of 94-98% is appropriate for the majority of patients. Those at risk of carbon dioxide retention (e.g. chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) should have a target of 88-92%.

Intravenous (IV) fluids should be started, often 500 mL of a crystalloid over 15 minutes with reference to the patients’ haemodynamic status and co-morbidities. It is important to choose a crystalloid with a sodium content between 130-154 mmol/L.

Antibiotics are key and should be given without delay, the choice of antibiotics should be guided by local hospital guidelines. It should be an empirical antibiotic given intravenously. There are usually recommendations for treating ‘sepsis of unknown cause’ if the site of infection is unknown.

Three out

A minimum of two sets of blood cultures should be taken. Ideally, this should happen prior to administration of antibiotics though they should not be a cause for delay. Serum lactate should be obtained normally via a blood gas (arterial or venous) to help assess the patient’s status. Urine output should be measured ideally with a catheter with a careful fluid balance recorded.

Additional investigations

In addition to the SEPSIS-6 bundle, patients should undergo investigations to look for organ dysfunction and the suspected source of infection. When thinking about a source of infection, not all of these investigations will be required if the source is obvious from the history and clinical assessment.

- Organ dysfunction: Full blood count, U&E, CRP, Clotting screen, liver function tests, ongoing observations

- Source of infection: Chest x-ray (chest), urine MC&S (urine), CT abdomen/pelvis (Intrabdominal pathology), lumbar puncture (meningitis), blood film (malaria), joint aspiration (septic arthritis)

Senior review

All patients with sepsis should be discussed with a senior clinician and have ongoing monitoring. NICE guidelines NG51 recommend that all patients presenting with ≥1 high-risk criteria should be discussed with a consultant. If there is any deterioration or features of septic shock/MODS, patients should be discussed and reviewed by the intensive care team.

Overview

Shingles (herpes zoster) causes a characteristic vesicular rash that occurs due to reactivation of varicella-zoster virus (VZV).

Shingles is a viral infection caused by reactivation of varicella-zoster virus (VZV). The condition, also known as herpes zoster, causes a classic painful vesicular rash along the skin served by the single dermatome.

Primary VZV infection causes chickenpox, usually in children. Following resolution, the virus lays dormant in the dorsal root ganglia. In the advent of immunosuppression, the virus may reactivate leading to the classic vesicular rash along the skin served by the single dermatome.

Varicella-zoster virus

VZV is one of the human herpes viruses that is the cause of both chickenpox and shingles.

The human herpes viruses are a large family of DNA viruses that cause a range of infections in humans. VZV is also known as human herpes virus 3 (HHV-3).

VZV causes two distinct diseases depending on whether it is a primary VZV infection or reactivation:

- Primary VZV infection (chickenpox): characterised by a generalised pruritic vesicular rash, usually in children.

- Reactivation (shingles): characterised by a painful unilateral vesicular rash, restricted to a dermatomal distribution.

Shingles usually occurs due to alteration of the immune system. Age is the major factor in the development of shingles. This is because as we age, there is gradual deterioration in immune function known as immunosenescence. Any patient who is immunosuppressed for other reasons (e.g. systemic disease, cancer, post-transplantation) is at risk of shingles.

Risk factors

Age is the predominant risk factor for the development of shingles.

Any factor that suppresses the normal immune response can predispose to shingles.

- Age: up to 50% of patients who reach 85 years old will have experienced at least one episode of shingles

- Immunosuppression (e.g. chemotherapy, high dose steroids)

- Transplant recipients

- Autoimmune diseases: usually related to use of immunosuppressive medications

- HIV infection

- Other (e.g. co-morbid conditions such as CKD, COPD, diabetes)

Epidemiology

The lifetime risk of developing shingles is estimated at 20-30%.

Age is the major factor in developing shingles. The annual incidence in the UK is estimated at 1.85–3.9 cases per 1000 population. Up to 50% of patients who reach 85 years of age will have developed a single episode of shingles during their lifetime

Pathophysiology

The VZV lies dormant within the dorsal root ganglia.

Following a primary infection (i.e. chickenpox), VZV lies dormant with the dorsal root ganglia. When the immune system is weakened, it may extend out in a dermatomal distribution leading to the characteristic vesicular rash.

Patients with active lesions may transmit the virus to varicella naïve patients leading to development of chickenpox. Once the lesions are crusted over, they are considered non-infective.

Clinical features

Shingles classically causes a unilateral, erythematous, vesicular rash in a dermatomal distribution.

Shingles is characterised by a prodromal phase of paraesthesia and pain in the affected dermatome, which is followed by an erythematous maculopapular rash. This develops into clusters of vesicles (fluid-filled cysts), then pustules (pus-filled cysts), before bursting and crusting over.

The rash is unilateral and does not cross the bodies midline. Any dermatome may be affected including cranial nerves, but it most commonly occurs in the lumbar or thoracic dermatomes.

Signs and symptoms

- Paraesthesia

- Pain: throbbing, burning, stabbing (due to acute neuritis)

- Rash: erythematous maculopapular rash initially. Over several days groups of vesicles develop. Within 3-4 days these become pustular and then burst. By 7-10 days the lesions crust over in immunocompetent individuals.

- Scarring: hypopigmented or hyperpigmented areas can remain for months to years following an episode

- Systemic features (<20%): headache, fever, malaise, fatigue

- Hutchinson’s signs (see Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus)

Class vesicular rash of shingles affecting the T3 dermatome.

Image courtesy of Fisle (Wikimedia commons)

Abnormal presentations

Patients who are older or immunosuppressed may have more atypical presentations.

- Absence of vesicular lesions (more likely if elderly)

- Prolonged rash: new lesions developing >7 days after presentations (usually in immunocompromised)

- Zoster sine herpete: describes pain without rash (rarely occurs)

- Disseminated disease: features of pneumonia, encephalitis, hepatitis (at risk if severely immunosuppressed)

- Multiple dermatomes

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus

This refers to reactivation of Herpes zoster within the distribution of the trigeminal nerve.

Reactivation of Herpes zoster within the trigeminal nerve (fifth cranial nerve) is known as herpes zoster ophthalmicus and can be sight-threatening due to involvement of the cornea.

An important sign of Herpes zoster ophthalmicus is Hutchinson’s sign. This describes the presence of vesicular lesions on the side or tip of the nose that represents the dermatome of the nasociliary nerve (branch of the Ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve). This sign correlates highly with subsequent eye involvement.

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus affecting the right eye

Image courtesy of Dr. Partha Sarathi Sahana (flickr)

Ramsay hunt syndrome

Ramsay hunt syndrome refers to the reactivation of herpes zoster in the geniculate ganglion of the facial nerve.

It is characterised by facial nerve palsy associated with a vesicular rash affecting the ipsilateral ear, hard palate and anterior two thirds of the tongue. For more information see Ramsay hunt syndrome notes.

Diagnosis & investigations

The diagnosis of shingles is usually a clinical diagnosis based on the appearance of the classical rash.

The diagnosis of shingles is based on the classic presentation of a painful, unilateral vesicular rash in a dermatomal distribution.

PCR testing

If the presentation is atypical or the diagnosis is unclear, VZV can be confirmed with polymerase chain reaction (PCR). A swab taken from a suspected lesion can be sent to the laboratory for PCR. This method can detect VZV DNA through amplification.

Testing for immunosuppression

Shingles often occurs in elderly or immunosuppressed individuals. The presence of shingles in an otherwise ‘healthy’ individual should prompt investigation for immunodeficiency (e.g. HIV testing, immunoglobulins, cancer assessment).

Management

Consider admission to hospital in patients with severe shingles, complications or significant immunosuppression.

The majority of patients with shingles can be managed with oral anti-viral therapy (e.g. aciclovir), which should be prescribed within 72 hours of rash onset.

Anti-viral therapy

Consider oral aciclovir, valaciclovir, or famciclovir for the treatment of shingles in the following groups:

- Immunocompromised (non-severely and not systemically unwell)

- Non-truncal involvement

- Moderate to severe pain or rash

- Patients >50 years old (reduces incidence of post-herpetic neuralgia)

- Pregnancy (seek specialist advice before initiating treatment)

If patients present >72 hours after rash onset, anti-viral therapy may be considered up to one week following rash onset. However, there is likely minimal benefit in immunocompetent individuals.

Analgesia

The choice of analgesia in patients with shingles depends on the severity of pain.

- Mild pain: offer simple analgesia (paracetamol with or without NSAIDs if no contraindication)

- Severe pain: offer simple analgesia (as per mild pain) plus consider neuropathic agents (e.g. amitriptyline, gabapentin).

A short course of steroids may be considered in patients with severe pain within the first two weeks of rash onset. This can only be considered in immuncompetent patients alongside anti-viral therapy.

If there is persistent pain following resolution of skin lesions, treat for post-herpetic neuralgia (see complications).

Hospital admission

Patients may require inpatient admission for intravenous antiviral therapy and monitoring, or management of complications, in the following groups:

- Severe complications (e.g. meningitis, encephalitis)

- Herpes zoster ophthalmicus

- Severely immunocompromised

- Severe infection (e.g. severe rash, widespread, or systemic features)

- Immunocompromised child

Basic advice

Patients remain infectious until all lesions have crusted over, which usually occurs at 5-7 days. It is important to avoid contact with the following groups:

- People who have not had chickenpox

- Immunocompromised individuals

- Babies <1 month

Good hygiene advise including avoiding sharing clothes, hand hygiene and avoiding work, school or day care (if lesions are weeping) is important.

Post-exposure prophylaxis

Varicella zoster immunoglobin refers to a scarce product of pooled antibodies against VZV. It may be offered to VZV antibody negative pregnant woman (≤ 20+0 weeks) who have had significant exposure to chickenpox or shingles. It may also be offered for severe neonatal infections.

Vaccination

A shingles vaccination may be offered to patients aged 70 years old if there are no contraindications. It is a live attenuated vaccine (Zostavax®) that cannot be administered to pregnant woman or certain immunosuppressed groups due to risk of disseminated infection.

The vaccine is effective at reducing the incidence and severity of shingles including post-herpetic neuralgia.

Complications

A number of serious complications may develop secondary to shingles.

Complications associated with shingles may range from mild to severe depending on age, co-morbidities and underlying immunocompetence.

- Scarring: hypo- or hyperpigmented areas

- Post-herpetic neuralgia (see below)

- Secondary bacterial infection

- Ramsay hunt syndrome

- Herpes zoster ophthalmicus

- Motor neuropathy

- CNS involvement: encephalitis, meningitis, myelitis

- Disseminated infection

Post-herpetic neuralgia

This is the most common complication associated with shingles and describes pain that is persistent, or appears more than, 90 days after the rash onset.

Post-herpetic neuralgia is due to neuritis and nerve damage in the affected region. Post-herpetic neuralgia is more common in older patients and rare in patients <50 years old.

Treatment options include:

- Conservative: wearing loose clothes, consider protecting sensitive areas and applying cold packs

- Mild to moderate pain: simple analgesia (paracetamol with or without codeine) or topical treatments (e.g. capsacin cream or lidocaine plaster)

- Uncontrolled with simple analgesia: consider neuropathic agents (e.g. amitriptyline, duloxetine, gabapentin, or pregabalin)