Overview

Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) is the most common form of leukaemia in adults in Western countries.

Leukaemia

Leukaemia refers to a group of malignancies that arise in the bone marrow. They are relatively rare but together are the 12th most common cancer in the UK, responsible for around 4,700 deaths a year.

There are four main types:

- Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML)

- Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL)

- Chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML)

- Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL)

Presentation, prognosis and management all depend on the type and subtype of leukaemia.

Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia

CLL is considered a lymphoproliferate disorder of B lymphocytes, which results from an abnormal clonal expansion of B cells that resemble mature lymphocytes. This leads to widespread lymphadenopathy and secondary complications such as immune deficiency and cytopaenias.

CLL can present with a wide range of clinical manifestations relating to the condition or associated complications. Patients may be asymptomatic with indolent disease that remains stable for many years. Alternatively, patients may have progressive disease leading to death within 2-3 years of diagnosis.

Epidemiology

The incidence of CLL increases with age.

The incidence of CLL is estimated around 4.2 per 100,000 per year and the condition is more common in men. The average age at diagnosis is around 72 years old. However, just over 10% of patients may be diagnosed before 55 years old.

Aetiology and pathophysiology

The aetiology of CLL is incompletely understood.

The development of CLL occurs secondary to sequential genetic alterations and changes to the bone marrow microenvironment. Collectively, this promotes the formation of a clone of B lymphocytes that subsequently undergo further genetic changes that promotes proliferation leading to CLL.

Genetic alterations

Many genetic alterations may be seen in CLL. As with all cancers, these promote abnormal cell growth, cell survival and genomic instability:

- TP53 mutation: TP53 is the ‘guardian of the genome’ and major tumour suppressor gene. The mutation is linked to a poor response to treatment.

- 11q and 13q14 deletions

- Trisomy 12: presence of an extra 12th chromosome

- Overexpression of BCL2 proto-oncogene: suppresses programmed cell death (i.e. increases cell survival)

- NOTCH1 mutation: normally regulates haematopoietic cell development

Natural history

An initial inciting event or abnormal reaction to an antigen stimulus leads to genetic alterations that allow the formation of a clone of B lymphocytes. This is a premalignant disorder, which is referred to as monoclonal B cell lymphocytosis (MBL). Overtime, further genetic mutations and bone marrow microenvironment changes promote the progression to CLL. This transformation from MBL to CLL occurs at a rate of 1% per year.

A proportion of patients who develop CLL may remain asymptomatic for many years. However, others may get rapidly progressive disease with complications associated with the defective immune function including cytopaenias and hypogammaglobulinaemia (i.e. low antibody levels). This can lead to recurrent infections, bleeding and features of anaemia. The symptomatic stage of CLL is characterised by progressive lymphadenopathy, which includes splenomegaly and hepatomegaly, that occurs due to the accumulation of incompetent lymphocytes.

Clinical features

The hallmark feature of CLL is lymphadenopathy due to the infiltration of malignant B lymphocytes.

A large proportion of patients may be asymptomatic. Therefore, the condition is detected on routine blood tests or the finding of abnormally enlarged, but painless, lymph nodes.

Symptoms

- Weight loss

- Fevers

- Anorexia

- Night sweats

- Lethargy

Typical ‘B’ symptoms may be seen in 5-10%, which is classically associated with lymphoma. This refers to fever, weight loss and drenching night sweats.

Signs

- Lymphadenopathy: seen in 50-90% of patients. Most commonly cervical, supraclavicular and axillary nodes.

- Hepatomegaly: 15-25% at diagnosis. Usually mild hepatomegaly.

- Splenomegaly: 25-55% of cases.

Features associated with complications

- Autoimmune haemolytic anaemia: pallor, dyspnoea, weakness, dizziness

- Immune thrombocytopaenia: petechiae, bruising, mucosal bleeding

- Hypogammaglobulinaemia: recurrent infections (organ specific)

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of CLL is based on the presence of persistent lymphocytosis.

The diagnosis of CLL is principally based on the presence of excess lymphocytes on full blood count that are found to be clonal (i.e. all of the same type). Clonality can be assessed by flow cytometry, which is a process that immunophenotypes cells. In other words, it can detect antigens expressed on the surface of cells, which are shared by the clonal lymphocytes.

Diagnosis is based on the 2018 international working group CLL (iwCLL) guidelines, which utilise the absolute B lymphocyte count, characteristic immunophenotype features, and presence or absence of disease manifestations. These manifestations include lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, disease-related cytopaenias or disease-related symptoms.

We have simplified the diagnostic criteria below:

- CLL: Absolute B lymphocyte count >5.0 x10^9/L for >3 months with characteristic immunophenotype*

- CLL: Absolute B lymphocyte count <5.0 x10^9/L but ≥1 cytopenias due to bone marrow infiltration with typical CLL cells

- MBL: Absolute B lymphocyte count <5.0 x10^9/L and no disease manifestations of CLL

- SLL: Absolute B lymphocyte count <5.0 x10^9/L with nodal, splenic or extra-medullary involvement, but no cytopenias

*NOTE: characteristic immunophenotype findings refer to expression of typical B-cell associated antigens (CD19, CD20, CD23), expression of CD5 T-cell antigen (also found on some mature B cells) and low levels of surface membrane immunoglobulins.

Clinical and laboratory evaluation

The majority of patients with CLL are diagnosed incidentally on a full blood count.

The principle investigation in CLL is the full blood count (FBC). This enables review of blood counts (i.e. haemoglobin, platelets, white cells) and the differentiation of white cells (e.g. lymphocytes, neutrophils).

As part of CLL work-up, patients require a thorough clinical examination and laboratory evaluation (i.e. blood tests). This enables confirmation of CLL, staging of the disease and assessment of disease-associated complications.

Clinical examination

Essential to determine the presence or absence of lymph node involvement including specific sites, splenomegaly and hepatomegaly.

Bloods

- FBC: lymphocytosis (may be extremely high) and normocytic anaemia

- Routine biochemistry: U&E, bone profile, LFTs

- Blood film: discussed below

- Haemolysis screen (at risk of AIHA): Direct antiglobulin test (DAT), haptoglobin, LDH, unconjugated bilirubin, reticulocytes

- Immunoglobulins: at risk of secondary hypogammglobulinaemia

Cytogenetics and immunophenotyping

Immunophenotyping is used to confirm that lymphocytosis is secondary to circulating clonal B lymphocytes. Completed using flow cytometry of peripheral blood.

Cytogenetics involves looking for characteristic mutations. Specific mutations can be completed prior to treatment as it will influence decision making (e.g. TP53 mutation).

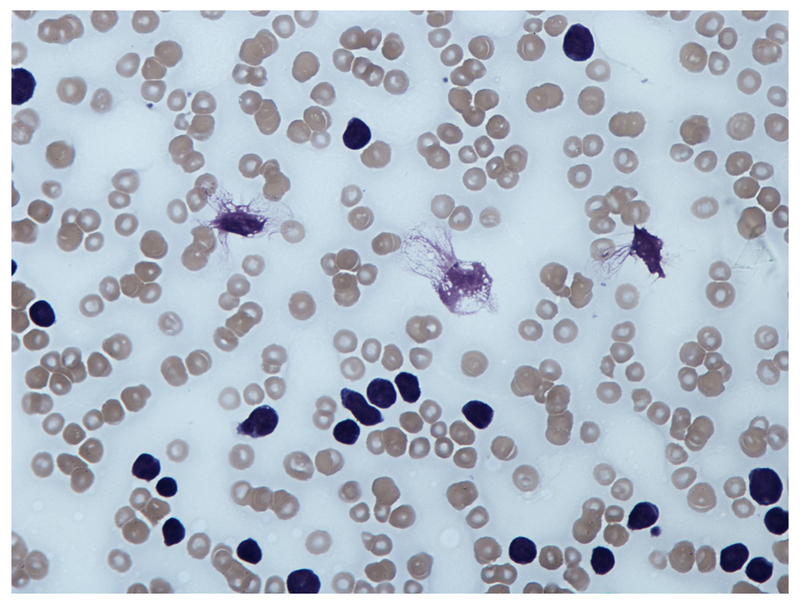

Blood film

A blood film will confirm the presence of lymphocytosis and characteristically shows smear or ‘smudge’ cells. These are artefacts due to damaged lymphocytes that occur during preparation of the slide.

Blood film showing ‘Smear cell’

Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons

Bone marrow assessment

Assessment of bone marrow by aspirate or trephine biopsy is usually not required unless there is concern for an alternative diagnosis. If completed, will show replacement of normal marrow with excess lymphocytes.

May be indicated to show complete response to treatment or to determine the cause of cytopaenias.

Imaging

Routine use of imaging (e.g. CT chest, abdomen, pelvis) is usually not required. However, CT may be indicated if concerns about lymphomatous transformation, to assess disease extent pre- and post-intensive treatment, or when a significant complication is suspected.

Ultrasound may be used to confirm hepatosplenomegaly. Chest x-ray may be useful to exclude an alternative diagnosis, assess for infection or look for pulmonary lymphadenopathy.

Other investigations

- Lymph node biopsy: can be performed if the diagnosis is unclear or there is concern about lymphomatous transformation.

- Virology: important prior to initiation of treatment. Hepatitis B, hepatitis C, HIV +/- CMV

Staging

CLL can be staged according to the Binet or Rai systems.

Both the Binet and Rai systems are based on clinical features and laboratory evaluation (e.g. blood counts). They provide prognostic information in CLL.

Binet staging

This staging system is based on the number of lymphoid sites affected on clinical examination (cervical nodes, axillary nodes, inguinal nodes, spleen, and liver) in combination with presence or absence of anaemia/thrombocytopaenia.

- Stage A: <3 lymphoid sites

- Stage B: ≥3 lymphoid sites

- Stage C: presence of anaemia (<100 g/L) and/or thrombocytopaenia (<100 x10^9/L)

NOTE: an area is counted as one regardless of whether unilateral or bilateral.

Rai staging

This staging system is based on the expected natural progression of CLL. As the burden of abnormal B lymphocytes increases, there is progressive lymphocytosis in the blood and bone marrow. This subsequently affects nodal tissue (e.g. lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly) and finally leads to bone marrow failure.

It was originally divided into five stages, which were subsequently grouped into three:

- Stage 0 (lymphocytosis): 25% at initial diagnosis

- Stage I-II (lymphocytosis + lymphadenopathy + organomegaly): 50% at initial diagnosis

- Stage III-IV (lymphocytosis + anaemia or thrombocytopaenia +/- lymphadenopathy/ organomegaly): 25% at initial diagnosis

Prognostic factors

In addition to the Binet and Rai system, other prognostic factors can be used to guide treatment.

- Lymphocyte doubling time: number of months it takes for the lymphocyte count to double.

- Genetic abnormalities: cytogenetic analysis of mutations including TP53, del(11q), trisomy 12, and del(13q)

- Beta-2-microglobulin: correlates with disease stage and tumour burden

- Others: e.g. Mutated immunoglobulin heavy chain variable genes, CD23 positivity and ZAP-70 positivity, among others.

Management

A variety of treatment options now exist for the management of CLL.

A watch and wait strategy may be appropriate in patients with asymptomatic, indolent disease without poor prognostic factors. This is usually for asymptomatic patients with Binet stage A/B or Rai stage <3.

Patients may have regular assessment and full blood count at 3 monthly intervals. At 12 months, treatment decisions can be decided based on the trajectory of the condition or develop of active/symptomatic disease.

Indications for treatment

Active disease needs to be clearly documented to initiate treatment. This means at least one criteria from the iwCLL needs to be met. We have simplified the criteria below:

- Bone marrow failure (Hb < 100 g/L, plts <100 x10^9/L)

- Massive, progressive or symptomatic splenomegaly (≥6 cm below costal margin)

- Massive, progressive or symptomatic lymphadenopathy (≥10 cm)

- Progressive lymphocytosis (≥50% over 2 months or doubling time < 6 months)

- Autoimmune complications not responsive to steroids (e.g. ITP/AIHA)

- Symptomatic/functional extranodal sites (e.g. skin, kidney, lung, spine)

- Disease-related symptoms (e.g. significant weight loss, severe fatigue, >2 weeks of fever or ≥1 month of night sweats without infection)

Treatment options

There are numerous therapies that can be used in the treatment of CLL. These depend on:

- Patient fitness and performance status

- Co-morbidities

- Mutational analysis (e.g. TP53 mutations)

- First-line treatment or treating relapse/refractory disease

The different pharmacological options are listed below. In general terms, treatment may be monotherapy or in combination. Some of the more common regimens are listed:

- Front-line therapy (no TP53 mutations): Fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab (FCR)

- Front-line therapy (TP53 mutations): Ibrutinib or Idelalisib and rituximab.

- Treatment of relapsed/refractory disease: Ibrutinib or Idelalisib and rituximab.

Pharmacotherapy

Different combinations of chemotherapy, small molecule inhibitors or monoclonal antibodies can be used in the treatment of CLL. We have detailed some of the choices that may be used:

- Chemotherapy

- Chlorambucil: cross-links DNA leading to damage and apoptosis. Given orally.

- Fludarabine: purine analog that inhibits DNA synthesis. Given orally or intravenously.

- Bendamustine: alkylating agent that cross-links DNA causing damage.

- Small molecule inhibitors

- Ibrutinib: tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Usually reserved for CLL with TP53 mutations

- Idelalisib: phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitor. Often used in combination with rituximab in relapsed/refractory disease.

- Venetoclax: BCL2 inhibitor. May be used in relapsed/refractory disease.

- Monoclonal antibodies

- Rituximab/Obinutuzumab/Ofatumumab: Anti-CD20 antibodies that target B lymphocytes (i.e. lymphocyte depleting agent)

- Other

- Corticosteroids: may be used as a single agent in extremely frail patients. May be prescribed to treat autoimmune complications including haemolytic anaemia and immune thrombocytopaenia.

Allogenic stem cell transplantation

An allogenic stem cell transplantation (AlloSCT) describes the process of transplantation of multipotent hematopoietic stem cells from a donor following chemotherapy to destroy the native bone marrow.

AlloSCT is a high-risk procedure that should only be considered in patients fit enough to undergo transplant. It is a potential option in patients who fail chemotherapy and BCR inhibitor therapy or those with TP53 mutations that do not respond to treatment or relapse. In addition, it can also be considered in those with Richter transformation (see complications).

Supportive care

Several aspects of care need to be addressed in all patients regardless of systemic therapy. These include:

- Vaccination: influenza, pneumococcal (ensure no contraindication with current therapy)

- Antibiotics for infections

- Consider intravenous immunoglobulin: treatment of secondary hypogammaglobulinaemia (i.e. IgG < 5g/L)

- Consider Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PJP) and herpes zoster prophylaxis: usually in patients on treatment for relapsed CLL

Complications

In some patients, CLL may transform into another lymphoproliferative disorder.

Histological transformation

- Richter transformation (3-7%): formation of an aggressive lymphoma. Associated with a rapid deterioration. Approximately 5-8 month median survival.

- Prolymphocytic leukemia (2%)

- Hodgkin lymphoma (0.5-2%)

- Multiple myeloma (0.1%)

Other complications

- Secondary infections: herpes zoster, PJP, bacterial infections

- Autoimmune complications: AIHA, immune thrombocytopaenia

- Hyperviscosity syndrome: patients with a significantly elevated lymphocyte count are at risk (i.e. > 30 x10^9/L)

- Secondary malignancies: increased risk of haematological (e.g. acute myeloid leukaemia) and solid-organ malignancies

Prognosis

Prognosis in CLL has improved with the use of new therapeutic agents.

The natural history of CLL is from an asymptomatic stage to a progressive, treatment-resistant phase that lasts 1-2 years.

The Binet and Rai staging systems also provide prognostic information. In Europe, the Binet system is widely used and provides median survival per stage. The following is according to the European Clinical Practice Guidelines for CLL:

- Stage A: median survival >10 years

- Stage B: median survival >8 years

- Stage C: median survival 6.5 years