Introduction

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is a common gastrointestinal emergency defined as bleeding with a source proximal to the ligament of Treitz.

An UGIB is a relatively rare, but potentially life-threatening condition. Patients commonly present with haematemesis and/or melaena and may have features of shock (e.g. hypotension, collapse).

Peptic ulcer disease, gastritis and oesophageal varices account for the majority of cases. Prompt recognition and management is essential to minimise morbidity and mortality.

Epidemiology

The incidence of acute UGIB is around 1 in 1,000 per year.

UGIB occurs more frequently in males than females (♀ 1: 2 ♂). It has a mortality of 7-10% which has not improved significantly over the past 50 years.

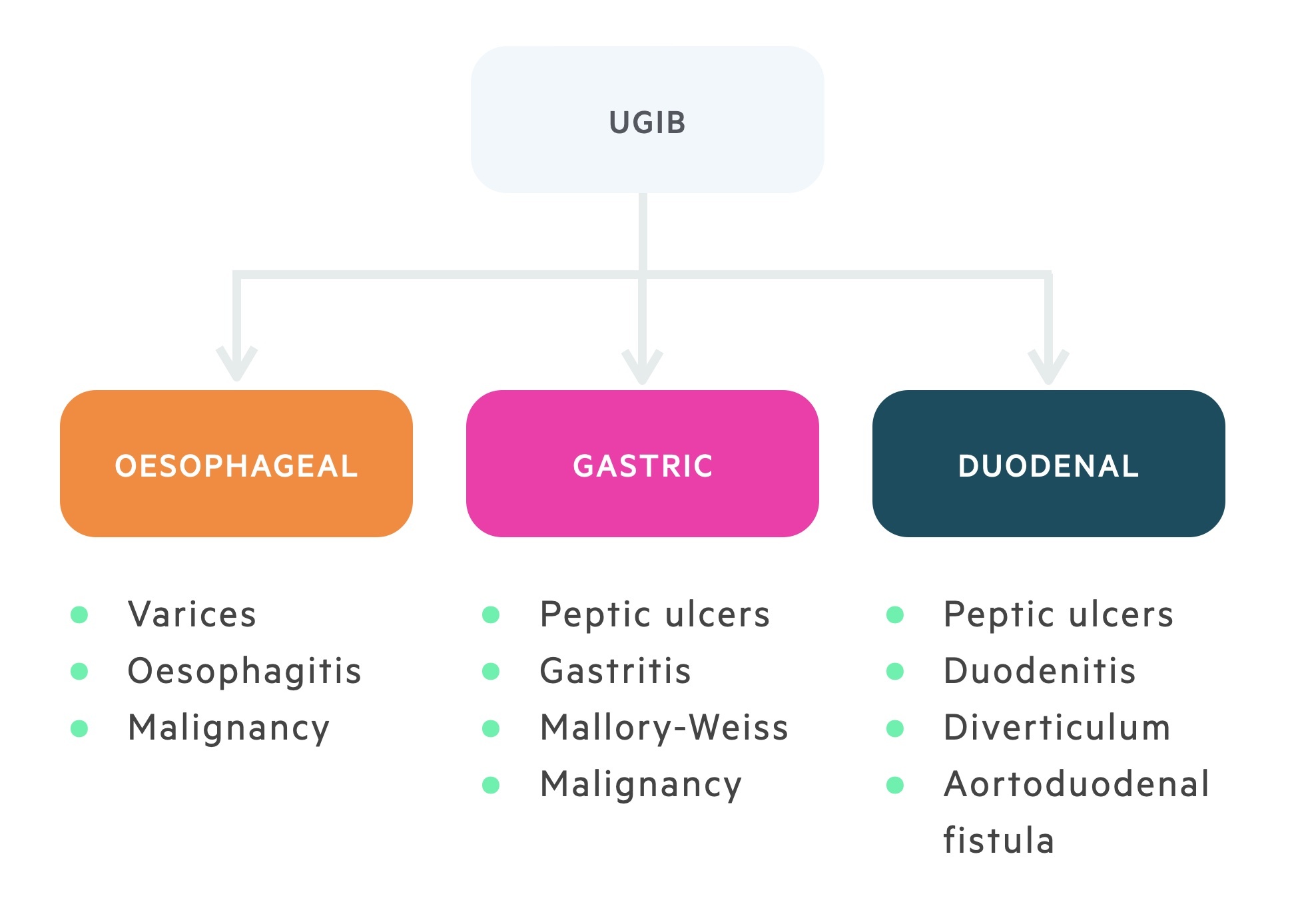

Aetiology

The causes of UGIB can be classified by anatomical location.

Oesophagus

- Oesophagitis

- Varices

- Malignancy

- Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD)

- Mallory-Weiss tear

Stomach

- Peptic ulcer disease

- Mallory-Weiss tear

- Gastric varices

- Gastritis

- Malignancy

Duodenum

- Peptic ulcer disease

- Diverticulum

- Aortoduodenal fistula

- Duodenitis

Other

There are many other causes of upper GI bleeding though they are relatively less common.

- Swallowed blood

- Bleeding disorders

- Dieulafoy’s lesion

- Aortoenteric fistula

- Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome)

- Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE, watermelon stomach)

Peptic ulcer disease

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is an umbrella term for the development of gastric and duodenal ulcers; it accounts for up to 50% of UGIB.

Peptic ulcer disease is strongly associated with Helicobacter pylori infection. The classical description of bleeding in PUD is of a posterior duodenal ulcer eroding through into the gastroduodenal artery. However, most UGIB secondary to PUD occurs due to erosions through smaller-sized blood vessels within the submucosa.

For more information, see our notes on Peptic ulcer disease.

Gastritis

Gastritis refers to inflammation of the lining of the stomach; erosive gastritis accounts for 15-20% of UGIB.

Gastritis refers to inflammation of the stomach associated with mucosal injury.

The term ‘gastritis’ is also used to describe the appearance of ‘inflamed’ mucosa on endoscopy. This can be rather misleading as many irritants (e.g. bile, NSAIDs, alcohol) can cause epithelial cell injury without resultant inflammation, which is termed ‘gastropathy’. Consequently, a biopsy is usually required during endoscopy to determine the extent of the damage.

Gastritis can be classified based upon location, timing or type of pathology:

- Antral or pangastritis

- Acute or chronic gastritis

- Erosive or non-erosive

Oesophageal varices

Oesophageal varices are abnormal, dilated veins that occur at the lower end of the oesophagus; they account for 10-20% of UGIB.

Oesophageal varices occur secondary to portal hypertension most commonly secondary to chronic liver disease / cirrhosis. They have the potential to cause massive haemorrhage.

Increases in portal pressure lead to the development of a collateral circulation to overcome the obstruction to flow in the portal system. The lower end of the oesophagus forms an important ‘portacaval anastomosis’ which allows the flow of venous blood from the portal system to the systemic circulation.

The other site of portacaval anastomoses are:

- Rectum

- Para umbilicus

- Retro-peritoneum

- Intra-hepatic (via patient ductus venosus)

Mallory-Weiss tear

A Mallory-Weiss tear refers to a liner mucosal laceration; they account for 5-10% of UGIB.

They typically occur at the gastro-oesophageal junction or within the gastric cardia. The classical description is of an episode of haematemesis (typically blood-streaked vomitus), which follows repeated episodes of retching / vomiting.

The lesion may be seen on upper GI endoscopy, but most cases resolve spontaneously.

Rare causes

HHT and GAVE are rare causes of UGIB.

Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome

Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome, also called hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), is a rare condition characterised by mucocutaneous telangiectasias (small, visible dilated blood vessels) and arteriovenous malformations (an abnormal connection between artery and vein). The condition is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern.

Gastric antral vascular ectasia

Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) is a rare cause of severe acute and chronic gastrointestinal bleeding. This may lead to chronic iron-deficiency anaemia or an acute UGIB. The pathogenesis of GAVE is largely unknown.

GAVE is also termed “watermelon stomach” because of the classical endoscopic appearance – ‘red tortuous ectatic vessels along the folds of the antrum’.

Risk factors

Several risk factors increase the likelihood of a patient developing an UGIB.

- NSAIDs

- Anticoagulants

- Alcohol abuse

- Chronic liver disease

- Chronic kidney disease

- Advancing age

- Previous PUD or H. pylori infection

NSAID-use

NSAIDs inhibit the synthesis of prostaglandins, which are gastroprotective.

Prostaglandins work by inhibiting enterochromaffin-like cells, which are involved in the secretion of histamine. Histamine stimulates parietal cells to secrete hydrochloric acid. Therefore, inhibition of prostaglandins leads to excessive HCl secretion and damage to the underlying mucosa.

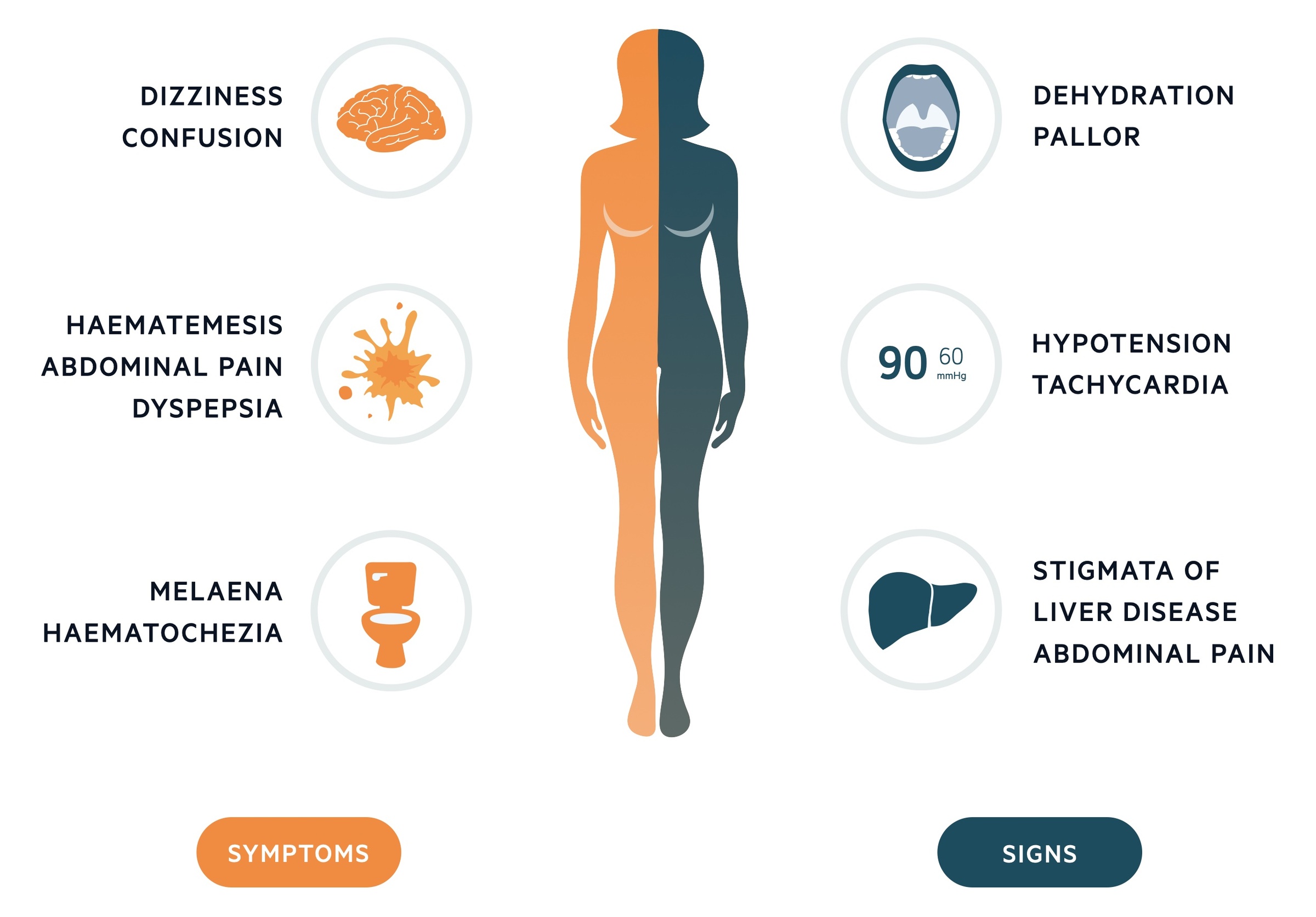

Clinical features

The two characteristic clinical findings of UGIB are haematemesis and melaena.

Haematemesis refers to vomiting blood. Haematemesis may present with bright red bleeding or as ‘coffee-ground’ vomitus.

Melaena is the passage of ‘black, tarry stool’, which has an offensive odour. The colour is due to partly digested blood.

Symptoms

- Haematemesis

- Dizziness

- Syncope

- Weakness

- Abdominal pain

- Dyspepsia

- Heartburn

- Melaena

- Haematochezia (passage of fresh blood per rectum)

- Weight loss

Signs

- Dehydration

- Pallor

- Confusion

- Tachycardia and hypotension

- Abdominal tenderness

- Melaena

- Haematochezia (10-15% of patients with acute, severe haematochezia have an UGIB)

- Stigmata of liver disease (e.g. spider naevi, ascites, hepatomegaly)

- Telangiectasia

Investigations & diagnosis

Upper GI endoscopy is the main investigation. It is both diagnostic and therapeutic.

Upper GI endoscopy should be completed within 24 hours of presentation. This may be required sooner in unstable patients after initial resuscitation. Performing endoscopy within 6 hours of consultation (early intervention) is not associated with lower 30-day mortality compared to endoscopy performed within 6-24 hours.

Bedside

- Regular observations (including lying / standing blood pressure if appropriate)

- ECG

- Monitor urine output

Blood tests

- Full blood count (FBC)

- Venous / arterial blood gas

- Urea & electrolytes (U&Es)

- Liver function tests (LFTs)

- Clotting

- Group & save with cross match

Imaging

- Chest x-ray: An erect film should be arranged if possible. Allows evaluation for aspiration, pneumomediastinum (oesophageal perforation) and free air under the diaphragm (perforation of abdominal viscus).

Special

- Upper GI endoscopy: Definitive diagnostic and therapeutic study. Allows the cause to be established and in many cases treated.

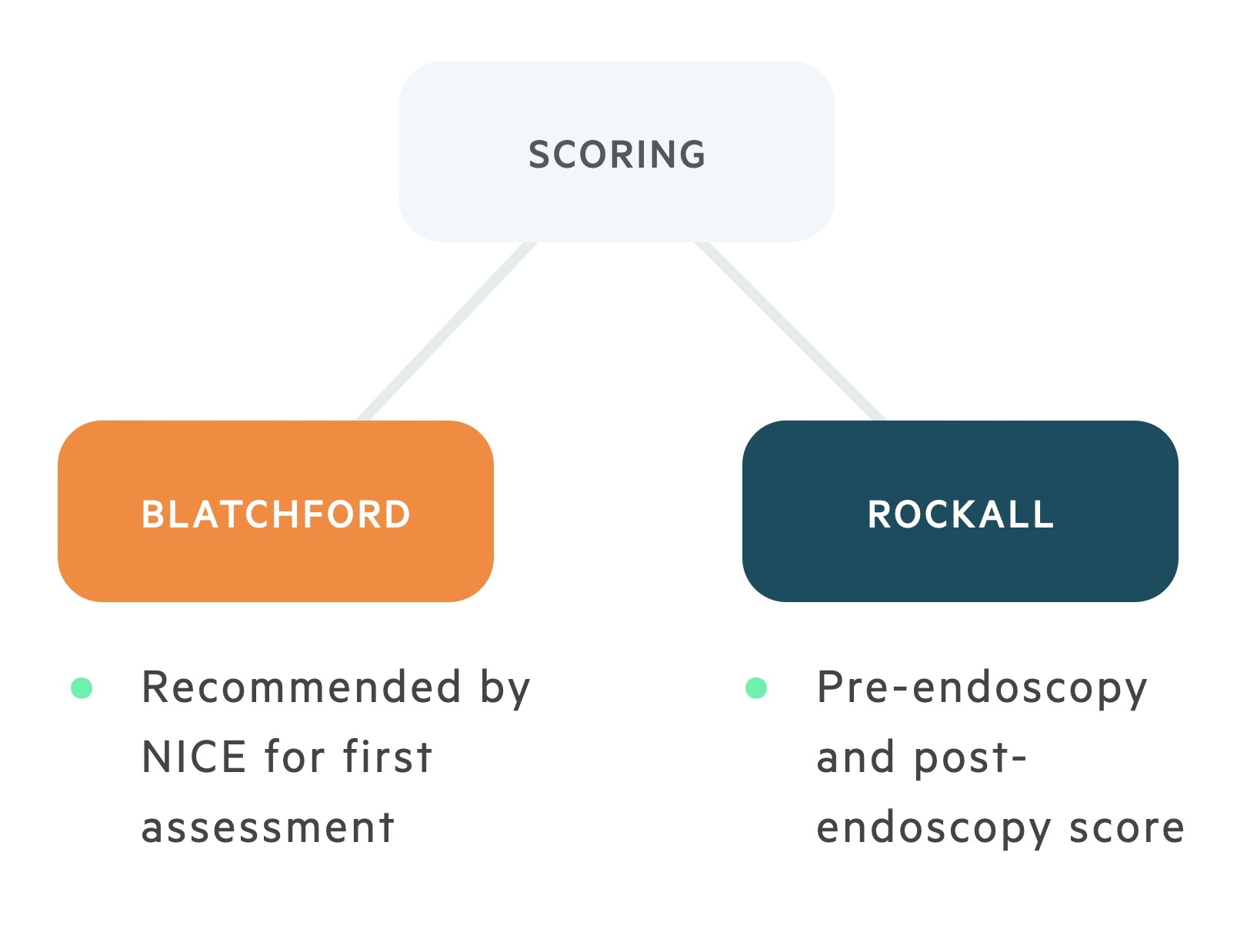

Scoring systems

Early risk stratification helps identify high-risk patients & need for prompt intervention. Two scoring systems are used in patients presenting with UGIB.

Blatchford score

The Blatchford score takes into account a number of different clinical findings, biochemical parameters and past medical history. NICE recommends it is used during the primary assessment, followed by the Rockall score post-endoscopy.

Similar to the Rockall score, a score of 0 on the Blatchford score is associated with a low risk of mortality and patients can be considered for early discharge and non-admission.

The British Society of Gastroenterology 2019 guidelines recommend outpatient management can be considered for a score ≤1 at presentation.

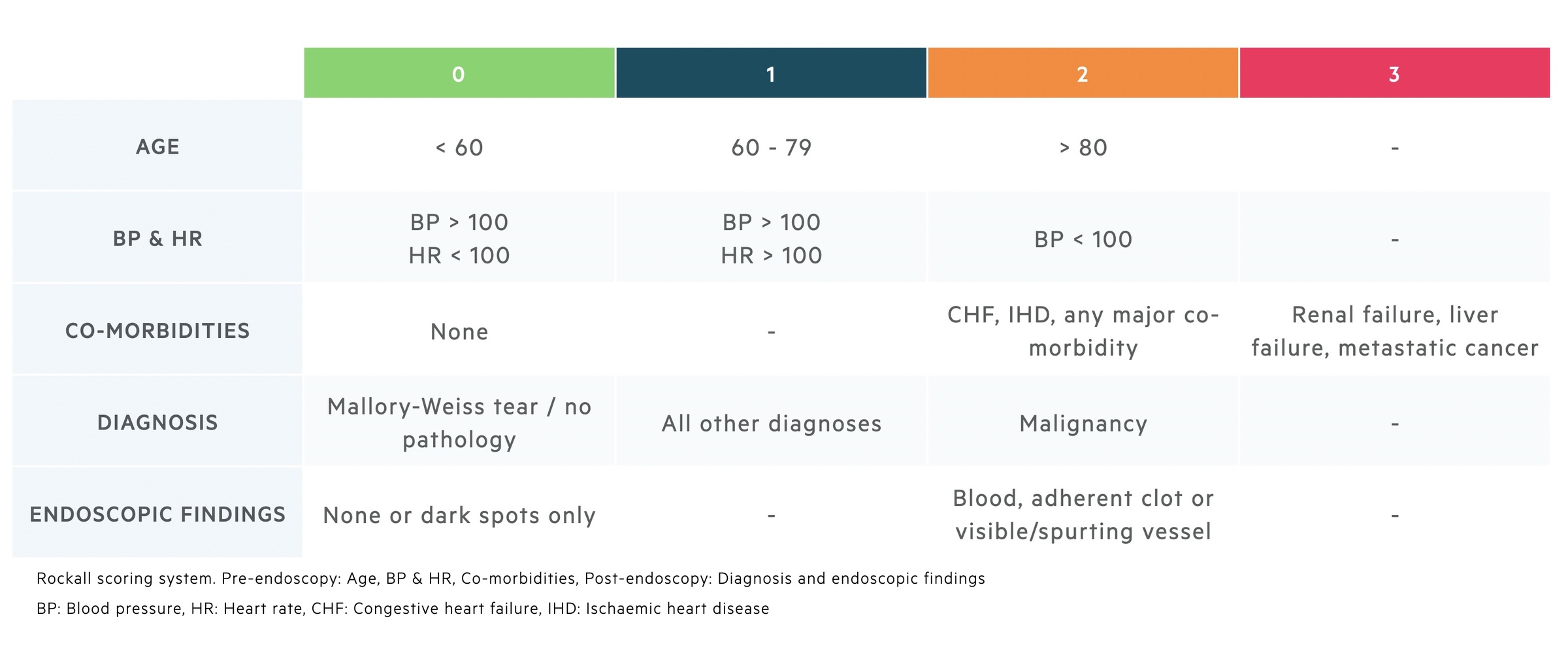

Rockall scoring

The Rockall score is comprised of both a pre- and post-endoscopy score that can be added together to give an overall value.

The pre-endoscopy score is composed of three parts:

- Age (0-2)

- Shock (0-2)

- Co-morbidity (0-3)

Patients with a score of 0 are at low risk of re-bleeding and death. This group of patients (approx. 15%) may be discharged early or not admitted.

The post-endoscopy score is composed of two sections:

- Diagnosis (0-2)

- Bleeding (0, 2)

This score can be remembered using the mnemonic ABCDE:

- Age

- Blood pressure (and heart rate)

- Comorbidity

- Diagnosis

- Endoscopic findings

Management

All patients presenting with an UGIB should initially be resuscitated with respects to airway (A), breathing (B) and circulation (C).

Resuscitation

- Airway

- Patent and protected

- Breathing

- Saturations

- Respiratory rate

- Breath sounds

- Circulation

- Blood pressure & heart rate

- ECG

- Establish IV access (two wide-bore cannula)

- Take blood (e.g. FBC, U&Es, clotting, LFTs, cross match)

- IV fluid if appropriate (0.9% normal saline)

- Consider blood products

Endoscopy

Following resuscitation, unstable patients should be transferred for an immediate endoscopy. It is recommended that all other patients have endoscopy within 24 hours of admission.

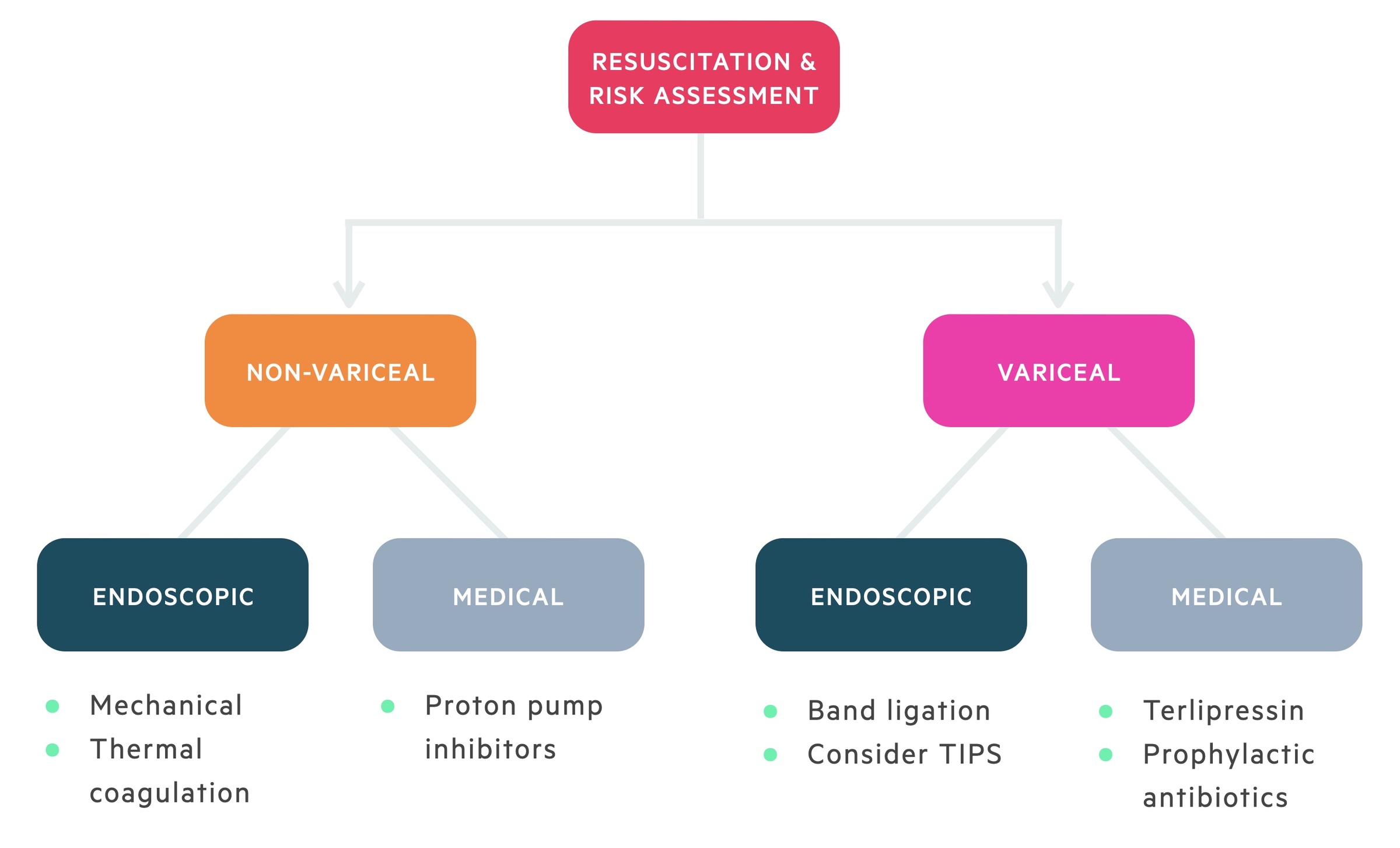

Management can then be divided according to ‘non-variceal’ or ‘variceal’ bleeding.

Non-variceal bleeding

The most common cause of non-variceal upper GI bleeding is peptic ulcer disease. The need for intervention depends on the characterisation of the ulcer, which can be classified using the Forrest classification (beyond the scope of these notes). Management below focuses mainly on that of peptic ulcer disease. Alternative pathologies may be treated slightly differently (e.g. argon photocoagulation for angiodysplasia).

A number of techniques can be employed at the time of endoscopy to treat non-variceal causes of UGIB. In general, dual therapy should be given (i.e. adrenaline plus another modality)

- Mechanical (e.g. clips) with adrenaline

- Thermal coagulation with adrenaline

Proton pump inhibitor therapy should be reserved for patients with a non-variceal UGIB with evidence of recent haemorrhage during endoscopy.

A repeat endoscopy should be completed in patients who re-bleed, or are suspected to be high-risk of re-bleeding. Unstable patients who re-bleed post-endoscopy should be offered radiological (e.g. embolisation) or surgical intervention.

Variceal bleeding

Pharmacological intervention

- Terlipressin (IV injection)

- Analogue of vasopressin (ADH)

- Causes splanchnic vasoconstriction

- This reduces portal pressures

- Prophylactic antibiotic therapy

- Reduces the risk of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

Endoscopic intervention

- Variceal band ligation (VBL)

- Completed acutely. Patients then need to undergo variceal banding programme every 2-4 weeks until varices have gone.

- Endoscopic sclerotherapy

- Alternative option to VBL that involves injection of a sclerosing agent.

Failed intervention

Patients may re-bleed despite endoscopic therapy. An initial re-attempt of variceal band ligation may be appropriate. If these attempts fail, further options include:

- Sengstaken-blakemore tube:

- Bridging therapy, at risk of oesophageal necrosis if left > 24 hours.

- Oesophageal stent:

- Alterantive to Sengstaken-blakemore tube.

- Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedure:

- Interventional radiological procedure to create a shunt between portal and systemic venous circulation to reduce portal pressure.

- A definitive treatment in appropriately selected patients.