Definition & classification

Crohn’s disease is a chronic inflammatory disorder, which can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract from mouth to anus.

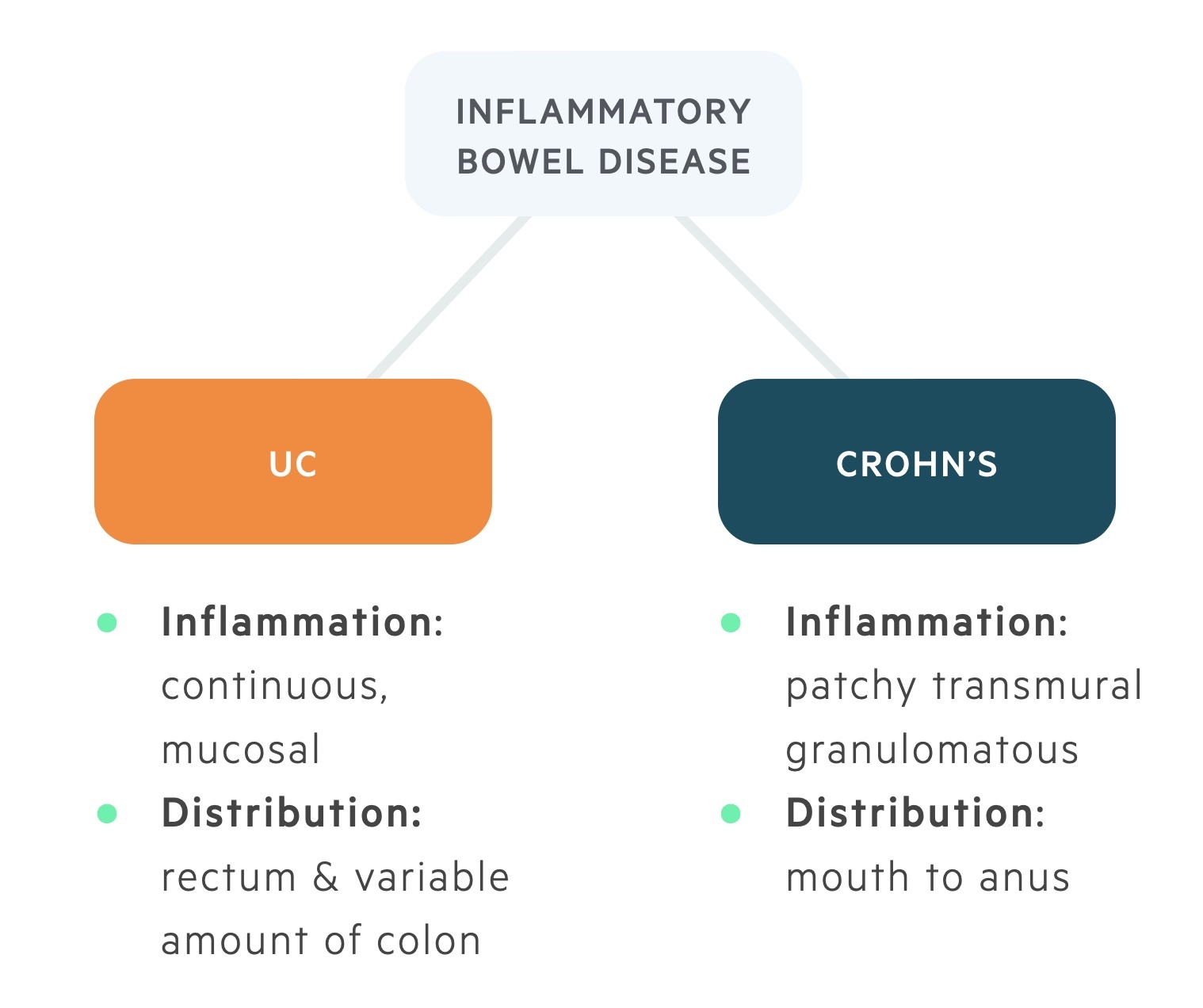

Inflammatory bowel disease

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is an umbrella term for two chronic inflammatory disorders of the gastrointestinal system:

- Ulcerative colitis (UC)

- Crohn’s disease (CD)

Though related, the two conditions have different pathologies, presentations and treatments. Whilst UC is a continuous inflammation of the mucosa starting in the rectum (in most cases) and limited to the colon, in CD transmural patchy inflammation is seen throughout the gastrointestinal tract.

Crohns disease

Crohns disease is a form of inflammatory bowel disease characterised by patchy, transmural inflammation of intestinal mucosa. It can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract from mouth to anus.

The overall incidence of CD is estimated to be 6 per 100,000 population, although this varies considerably between countries. It has bimodal incidence with peaks between the ages of 15-30 and 60-80 years old.

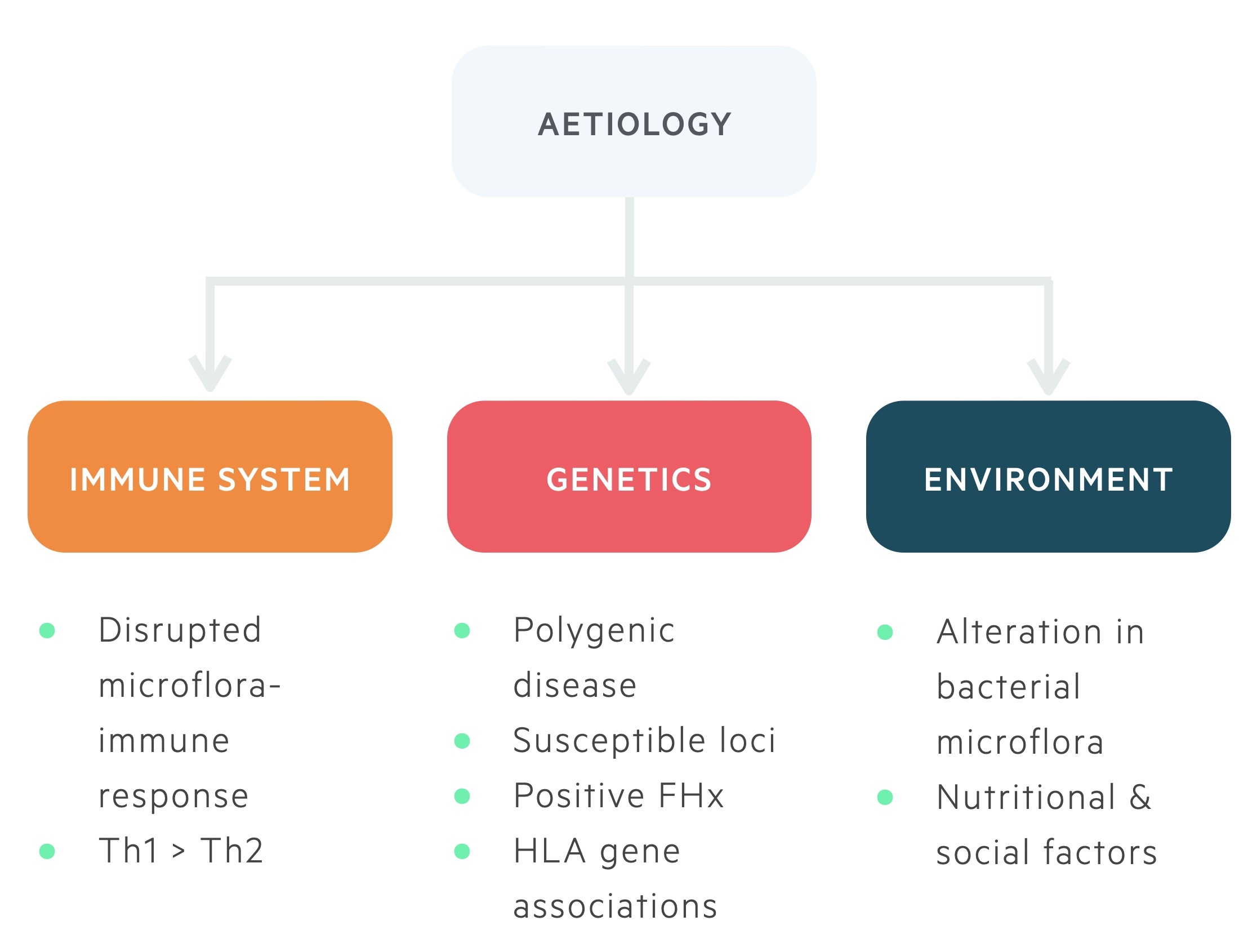

Aetiology

CD is thought to result from an abnormal immunological response to one or more aetiological factors within a genetically susceptible individual.

Genetic, immunological and environmental factors have all been implicated in the development of CD.

Genetics

CD is a polygenic disease (that is, multiple genetic loci increase the likelihood of developing CD, but do not directly cause it). There is an association between single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) in the NOD2 (CARD15) gene and CD. Additional genetic loci have also been identified that increase the risk of CD. With these in mind, it is important to be thorough when taking a history as patients may have a positive family history.

Immune system

Some research suggests that there may be an abnormal immunological response to normal intestinal microflora. Typically, a Th1 helper cell predominant response is seen leading to increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. TNF-alpha).

Environmental

Smoking increases the risk of CD, whereas it appears to be protective in UC. Smoking also has implications on disease severity and relapses.

There are also numerous other environmental factors associated with CD including western diets, antibiotic and contraceptive use.

Pathophysiology

CD can affect any part of the GI tract from the mouth to the anus.

Approximately 80% of patients have evidence of small bowel disease, which occurs most commonly in the distal ileum (terminal ileitis). 50% have evidence of small bowel and colonic disease. 33% have small bowel disease only. Around 20% of patients have colonic disease only. This can make it difficult to distinguish between CD and UC.

33% of patients suffer from perianal Crohn’s disease. This includes a variety of conditions that affect the perianal area (e.g. skin tags, fissures, fistulae, abscesses, or anal canal stenosis).

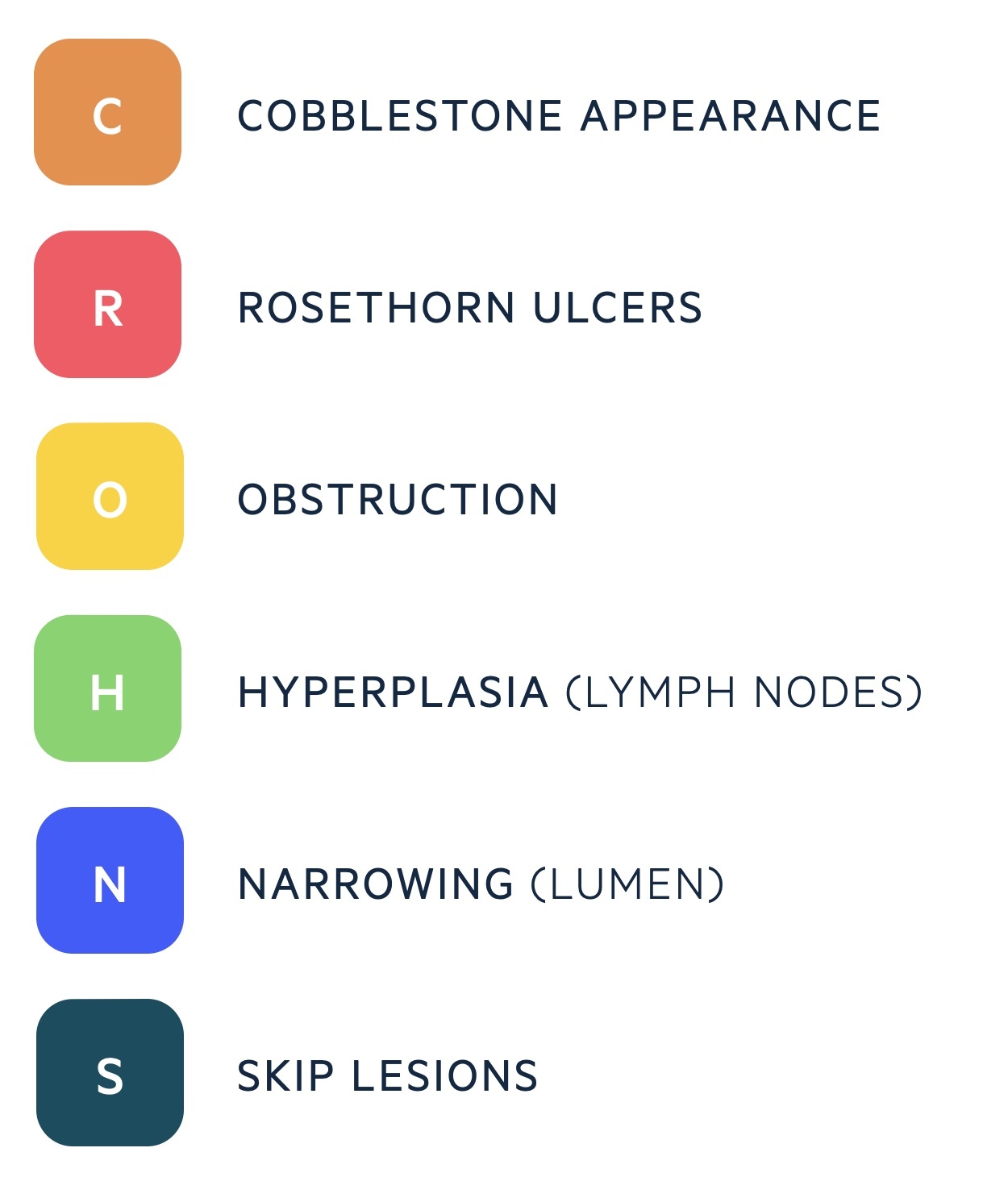

A number of pathophysiological changes occur in Crohn’s disease due to chronic inflammatory processes. These changes can be considered as macroscopic (seen during endoscopy) or microscopic changes (seen on histology).

Macroscopic

A number of signs may be seen at the time of endoscopy. A cobblestone appearance is classical, this is caused by small superficial ulcers which become deep and serpiginous (wavy margin). These may be transverse to longitudinal giving the mucosa its classical cobblestone appearance.

Bowel wall thickening, lumen narrowing, deep ulcers, fistulae and fissures may also be seen.

Microscopic

Inflammatory infiltration is noted on histology. This is characterised by lymphoid hyperplasia and non-caseating granulomas.

Skip lesions and transmural ulceration are also seen.

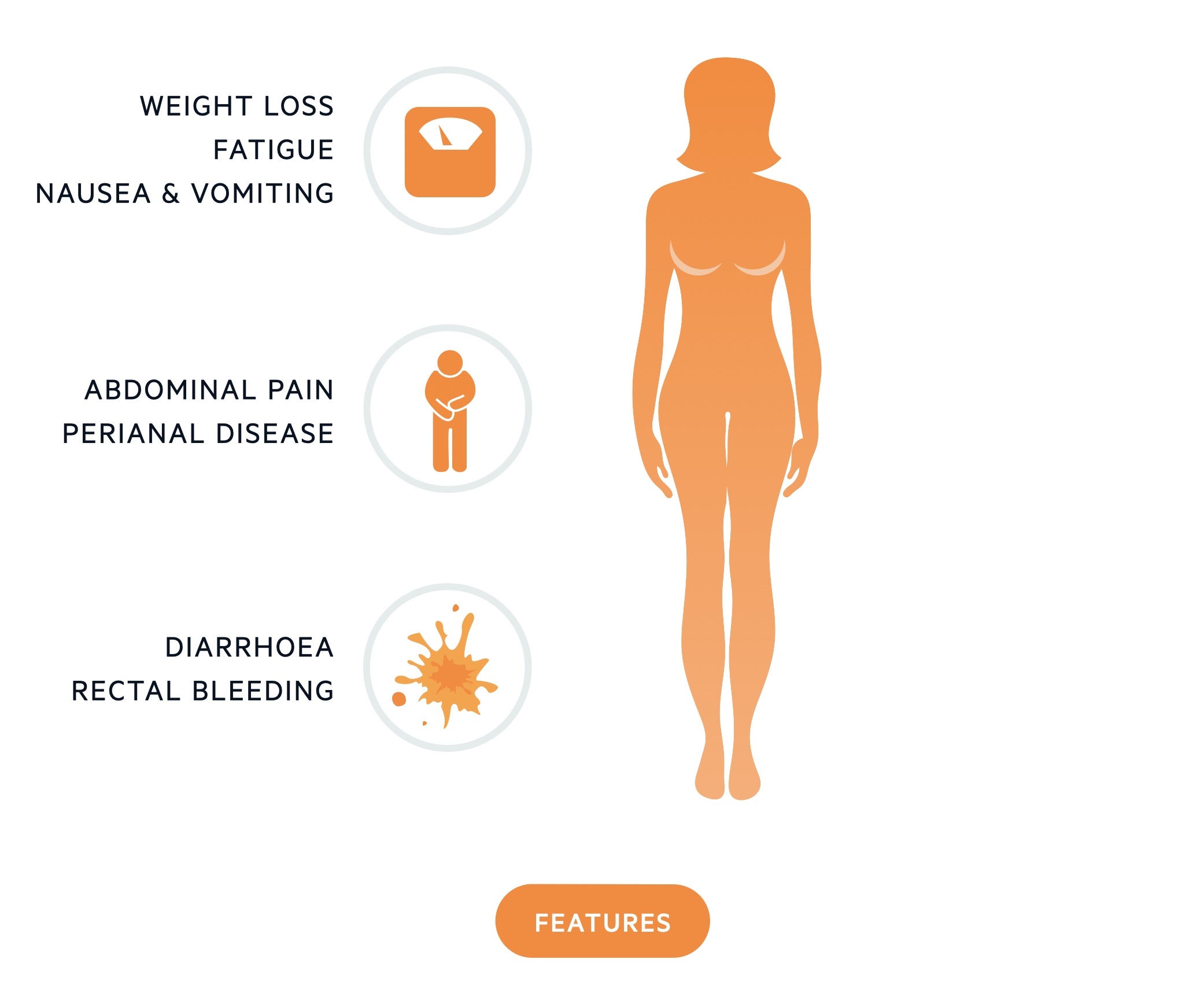

Clinical features

The clinical presentation of CD is variable, depending on both extent of disease and location of pathology.

Characteristic features of CD include diarrhoea, abdominal pain, weight loss, fever and fatigue. Patients with CD are at risk of a number of intestinal complication due to wall thickening, lumen narrowing and ulceration.

Symptoms

- Nausea & vomiting

- Fatigue

- Low-grade fever

- Weight loss

- Abdominal pain

- Diarrhoea (+/- blood)

- Rectal bleeding

- Perianal disease

Signs

- Pyrexia

- Dehydration

- Angular stomatitis

- Aphthous ulcers

- Pallor

- Tachycardia

- Hypotension

- Abdominal pain, mass and distension

Perianal disease

Perianal Crohn’s disease refers to a collection of perianal pathology commonly associated with the condition.

Perianal Crohn’s disease can affect up to one-third of patients. Skin tags, fissures, fistulae, abscesses and anal canal stenosis may all be seen.

Perianal symptoms are typically non-specific and inspection of the perineum is critical. Symptoms include rectal bleeding, pruritus and pain

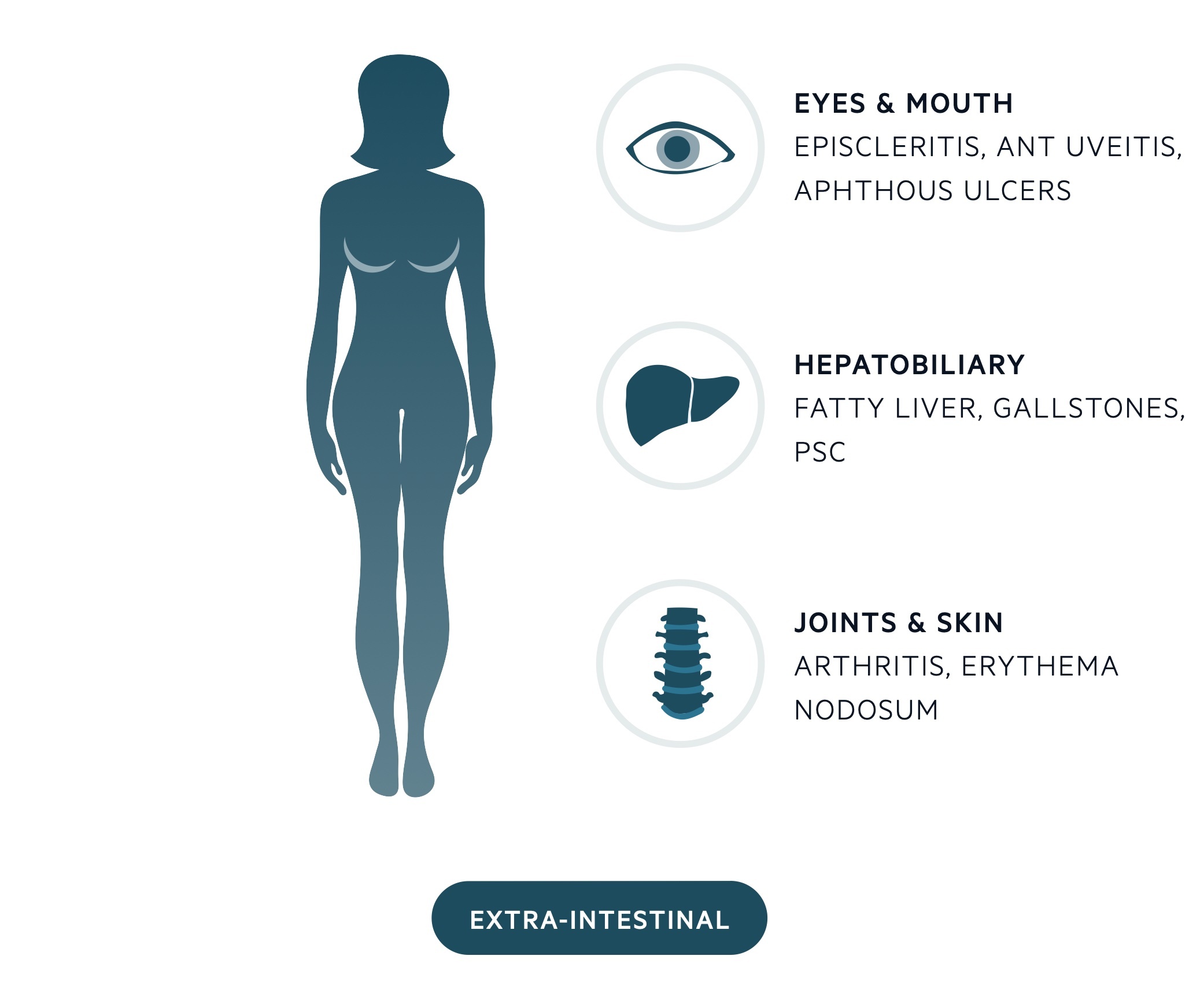

Extra-intestinal manifestations

Extra-intestinal manifestations (EIM) refer to the collection of clinical features that occur outside the gastrointestinal tract within CD.

Musculoskeletal

Musculoskeletal disease is the most common extra-intestinal manifestation. Two forms of arthritis are seen, type 1 and type 2.

- Type 1 is a pauciarticular peripheral arthritis related to intestinal disease activity.

- Type 2 is a polyarticular peripheral arthritis independent of intestinal disease activity.

Large joints are affected in up to 20% and ankylosing spondylitis and sacroiliitis may occur.

Skin

The skin is affected in around 10 – 20% of cases. Two of the lesions seen are erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum.

Erythema nodosum, a panniculitis, is characterised by reddened, raised, tender nodules.

Pyoderma gangrenosum presents with ulcerating nodules characterised by black (gangrenosum) edges and central pus (pyoderma).

Eyes & mouth

The eyes are involved in around 5% of cases. Episcleritis is the most common manifestation. Uveitis and conjunctivitis also occur.

Aphthous ulcers are often seen in Crohn’s patients, they may precede intestinal disease.

Hepatobiliary

The hepatobiliary system may be affected in a number of ways. Primary sclerosing cholangitis may occur though it is more common in UC.

Fatty liver disease and gallstones are seen with increased frequency.

Other

- Renal calculi

- Osteoporosis

- B12 deficiency

- Pulmonary disease

- Venous thrombosis

- Anaemia

Investigations and Diagnosis

The diagnosis of CD is based on macroscopic assessment (e.g. endoscopy) and histological evidence (e.g. biopsy) of inflammation typical of CD.

Bedside

- Observations

- ECG

- Urinalysis

- Stool microscopy, culture & sensitivities + ova, cysts & parasites + C. diff toxin (CDT)

- Faecal calprotectin:

- Sensitive marker of intestinal inflammation. Released following degranulation of neutrophils.

Bloods

- Full blood count

- Liver function tests

- Urea & electrolytes

- CRP

- Magnesium

- Haematinics

- Bone profile

- Clotting

Imaging

Abdominal X-ray: reveals bowel dilatation and perforation in the acute setting. Abdominal USS can be used to assess for wall thickening, free-fluid or abscess formation.

Computed tomography: demonstrates bowel wall thickening, bowel obstruction, abscesses, or fistulae. It is good at the assessment of extra-mural complications. Usually completed during acute presentation or looking for complications.

MRI small bowel: Magnetic resonance imaging is important in the evaluation of small bowel and perianal disease. Essential as part of initial ‘disease mapping’ and for looking at extent of small bowel disease including extent of inflammation and any strictures.

Barium follow through: helps to assess the extent of small bowel disease, particularly strictures. Rarely completed more as superseded by MRI.

Endoscopy

Colonoscopy: is used to assess the colon & terminal ileum. It provides an opportunity for tissue biopsy with a positive predictive value of 100%.

Upper GI endoscopy: is indicated in patients with gastroduodenal disease. A biopsy is needed to differentiate Crohn’s from other pathology (e.g. PUD).

Surgery

Examination under anaesthetic (EUA): allows the thorough assessment of CD associated perianal fistula’s.

Management

The general principle in the management of CD is to induce and then maintain remission.

In modern medicine, there are numerous pharmacological options for the management of CD, which include steroids, immunosuppressive agents and biologics. These have revolutionised the treatment of CD and prevent many patients from having to undergo multiple operations. Despite success with medications, surgery is still common in CD. Approximately 8 out of 10 patients with CD will need at least one surgery during their lifetime.

The choice of therapy will depend on disease severity, location, co-morbidities, patient preference and side-effects. Many patients will require different medications during their disease course.

Induce remission

In patients presenting with CD for the first time, or those who develop a flare of CD, the principle aim is to induce remission with nutritional alterations or corticosteroids.

In patients with mild-to-moderate CD, a course of exclusive enteral nutrition (EEN) can be considered over an 8 week period. This is particularly important for patients where steroid avoidance is desirable. EEN is essentially a liquid diet that excludes all food and drink except water. A standard regimen includes supplement drinks at 25-30 kcal/kg/day with 1g/kg/day of protein (lower calorie needs may be used in patients at refeeding risk).

In mild-to-moderate ileocaecal CD, patients can be offered budesonide 9 mg once daily for 8 weeks to induce remission. Budesonide has minimal systemic absorption. In patients who fail to respond to budesonide, or those with moderate-to-severe CD, systemic corticosteroids (e.g. prednisolone) should be prescribed as an 8 week weaning course.

In patients with moderate-to-severe CD there should be consideration of early introduction of immunosuppressive therapy (e.g. azathioprine or methotrexate). These medications help with long-term control, but are not useful at initially inducing remission, which is why they are combined with steroids. If patients have evidence of significant and/or extensive disease or other poor prognostic features early introduction of biologic therapy (e.g. infliximab) is recommended.

Maintenance therapy

Pharmacological options to maintain remission in CD predominantly include thiopurines, methotrexate and biologics. These are considered in patients with recurrent flares, moderate-to-severe disease, or poor prognostic features (e.g. extensive disease).

- Thiopurines (azathioprine and mercaptopurine): work through purine synthesis inhibition in lymphocytes leading to immunosuppressive properties. Must check TPMT enzyme activity before use. Homozygous mutations in TPMT can lead to dangerous bone marrow suppression. Major side-effects include pancreatitis and hepatotoxicity.

- Methotrexate: inhibits dihydrofolate reductase. Has both immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory properties. Must check liver and renal function before use. Given weekly. Major side-effects include bone marrow suppression, hepatotoxicity and pulmonary toxicity.

- Biologics: this refers to monoclonal antibodies. Options include infliximab/adalimumab (tumour necrosis factor (TNF) alpha inhibitors), vedolizumab (alpha-4/beta-7 integrin inhibitor) and ustekinumab (IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor). More biologic agents are being tested in clinical trials.

Surgical management

Surgery still forms a key part of management in CD. It is estimated that 8 out of 10 patients will have at least one operation during the course of their disease. Surgery may be used as a treatment for localised CD (e.g. localised ileocaecal Crohn’s), for patients wanting to avoid medical therapy or among patients that fail to respond to medical therapy. Alternatively, surgery may be needed to manage complications (e.g. perforation, abscess formation).

Patients with CD are at risk of perianal disease. A combination of surgery and pharmacological therapy is needed to manage perianal disease. The key aspects to perianal management include:

- Control perianal sepsis (e.g. antibiotics)

- Evaluation (e.g. MRI or examination under anaesthesia)

- Surgical intervention (e.g. abscess drainage or seton for fistula)

- Initiation or escalation of medical therapy

- Complex surgical planning: may be required for fistula’s not responding to initial therapy.

Surveillance colonoscopy

Patients with CD and ulcerative colitis are at increased risk of colorectal cancer. Currently, patients with IBD in the UK are offered surveillance ileocolonoscopy between 6-10 years following diagnosis to screen for dysplasia (abnormal cell growth, predisposes to malignancy). The frequency of surveillance endoscopy depends on the presence of dysplasia, extent of disease, disease activity and co-morbidities. Patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) are at a particularly high risk of cancer.