Overview

Lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) classically refers to bleeding that occurs distal to the ligament of Treitz.

The ligament of Treitz (suspensory ligament of the duodenum) marks the boundary between the upper and lower gastrointestinal (GI) tracts. It arises from the right crus of the diaphragm and suspends the duodenojejunal flexure. LGIB may be acute or chronic:

- Acute LGIB: presents with PR bleeding or altered blood with or without signs of shock. This note will focus on acute LGIBs.

- Chronic LGIB: typically asymptomatic and picked up incidentally following blood tests indicating iron deficiency anaemia. Signs or biochemistry of chronic LGIB are indications for urgent suspected cancer referral.

Acute LGIB is a potentially life-threatening condition. In the UK the most common cause is diverticular bleeding. Management depends upon the degree of bleeding, haemodynamic status and co-morbidities but often involves supportive care (e.g. blood transfusion) and sigmoidoscopy/colonoscopy.

Epidemiology

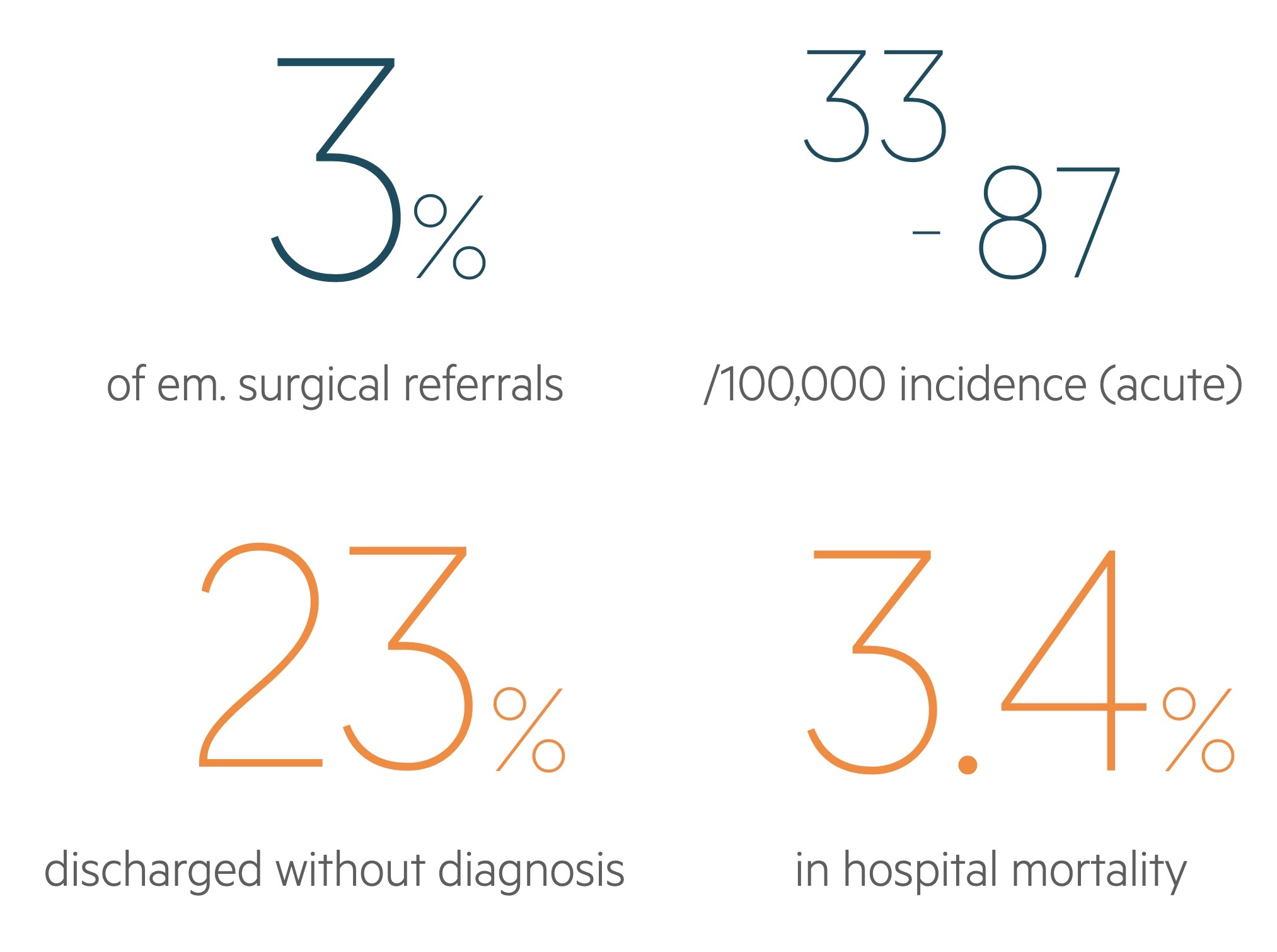

LGIB has an estimated incidence of 33-87 / 100,000.

It is responsible for around 3% of emergency surgery referrals. Incidence increases with advancing age as does the risk of hospitalisation and mortality.

Aetiology & pathophysiology

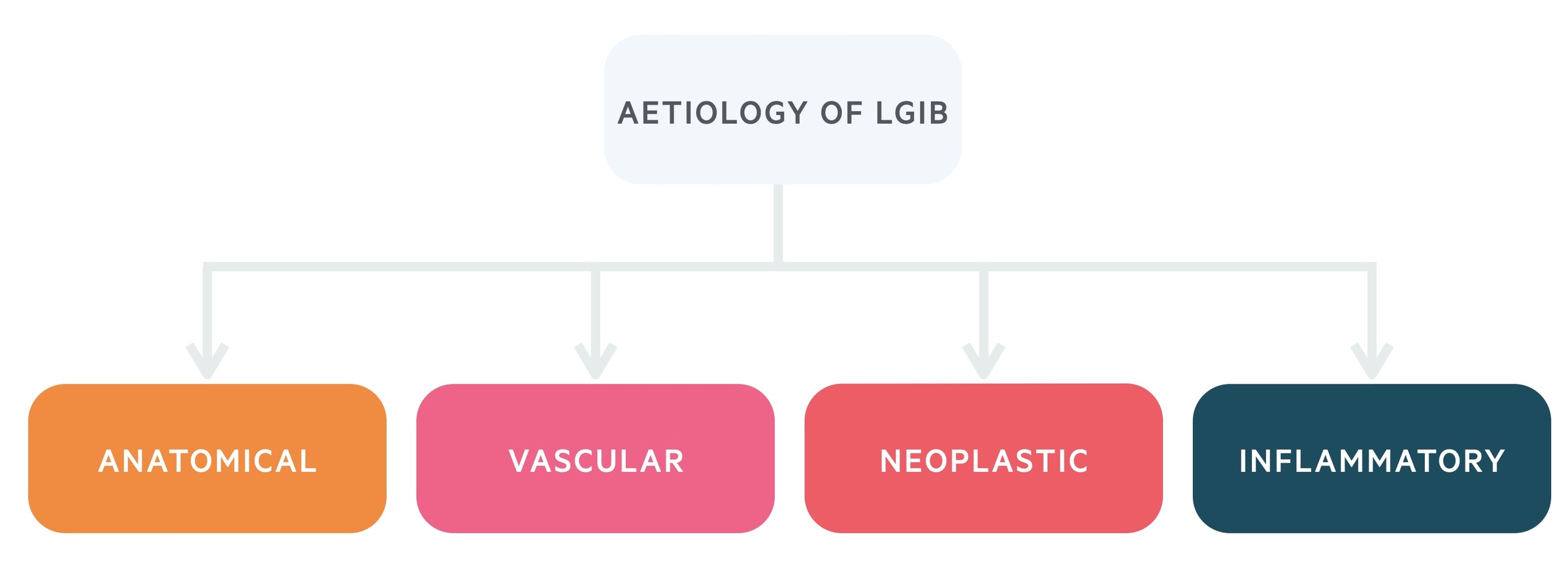

There are numerous causes of LGIB, which can be grouped according to the gross underlying aetiology.

Anatomical

Diverticulosis: Diverticulosis refers to the presence of diverticula – sac like protrusion of the colonic mucosa through the muscular wall. These commonly form in the colon at sites of weakness where vessels penetrate the muscular wall. Weakening of the vessel wall predisposes to bleeding. It is the most common cause of LGIB, accounting for up to 50% of cases. Symptomatic bleeding is characteristically painless (it normally occurs without diverticulitis). Up to 80% of cases will resolve with conservative management.

See our Diverticulitis notes for more.

Anorectal pathology: Is a common cause of LGIB, particularly in younger patients. It accounts for around 6-16% of LGIB. However, many cases of self-limiting bleeding may go unnoticed. Pathologies include:

- Haemorrhoids – dilatations in the anal cushions, which may engorge and prolapse through the anal canal.

- Fissures – tears in the anal mucosa, classically leading to exquisite pain on passing faeces (digital rectal examination may not be tolerated).

- Fistulas – abnormal connections between two epithelial-lined surfaces. They cause a variety of symptoms and may be associated with anorectal abscesses.

Vascular

Ischaemic colitis: This is the second most common cause of LGIB however it is rare that the bleeding is clinically significant, requires transfusions or results in shock. Typically occurs in elderly, co-morbid patients with arrhythmia’s, hypotension or on vasopressors.

Angiodysplasia: Angiodysplasia refers to the presence of an arteriovenous malformation (AVM) located within the submucosa. An AVM is an abnormal connection between an artery and vein. It can account for up to 3% of LGIB. Bleeding is usually less vigorous than other causes of LGIB, such as diverticular disease, although some patients may require interventional treatment to help locate and treat bleeding lesions. Angiodysplasia in the presence of aortic stenosis is called Heyde’s syndrome.

Neoplastic

Polyps: Polyps are benign neoplastic proliferations of the colonic epithelium which possess small malignant potential. Multiple polyps may be seen in a number of familial conditions (e.g. familial adenomatous polyposis, hereditary non-polyposis colorectal carcinoma).

Malignancy: Colorectal carcinoma is a common, and significant, cause of LGIB that occurs more commonly in males. It accounts for around 10% of cases of rectal bleeding in the over 50’s. Though it commonly causes chronic occult LGIB (leading to iron-deficiency anaemia) it can at times cause brisk bleeding.

See our notes on Colorectal cancer for more.

Inflammatory

Inflammatory bowel disease: Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease may both cause lower GI bleeding thought Haematochezia is more commonly seen in UC.

See out notes for more on Ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease.

Infective causes: The presence of bloody diarrhoea may suggest a number of infective aetiologies which cause dysentery (low-volume, bloody diarrhoea with abdominal pain).

Clinical features

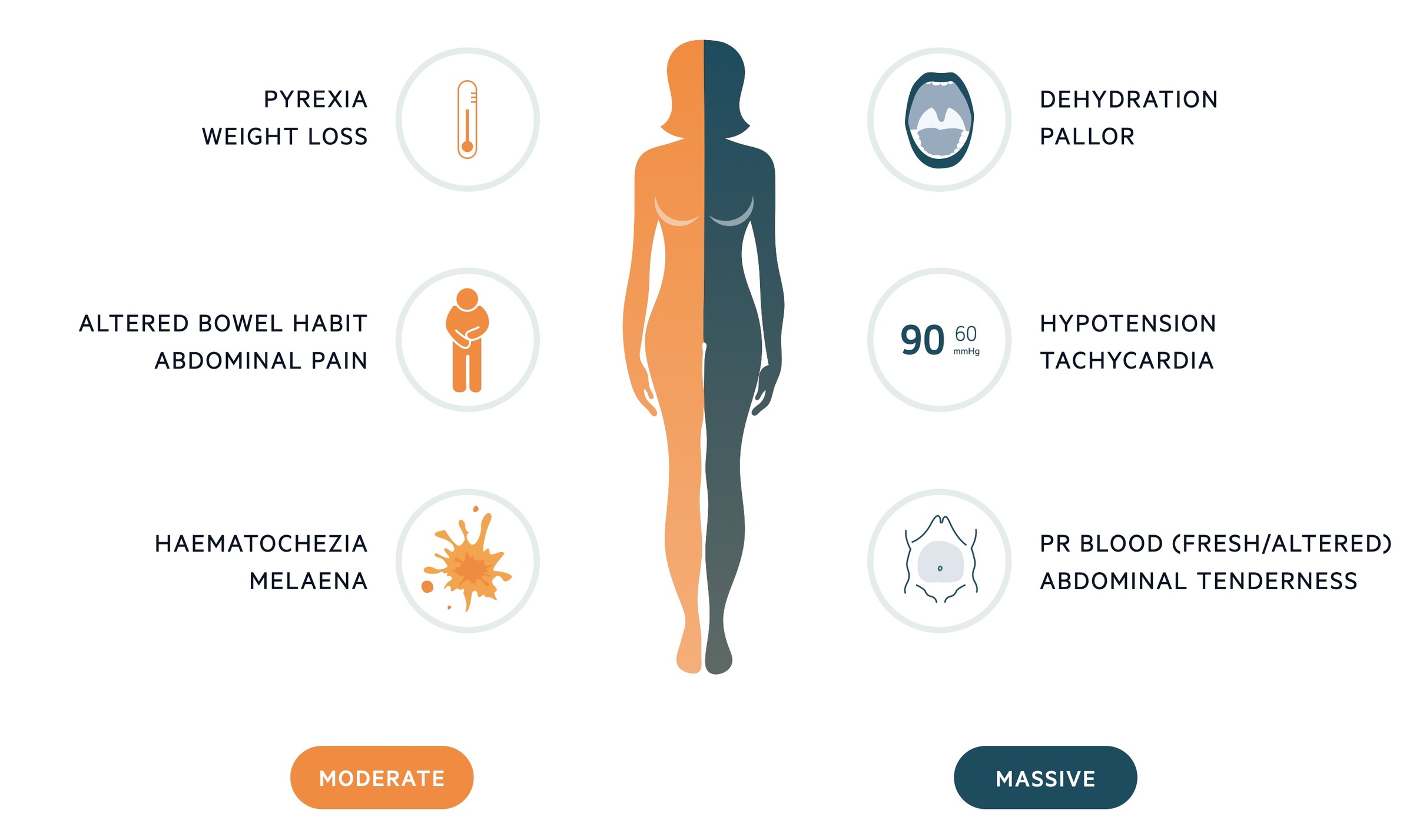

The presentation of LGIB is dependent on the extent of bleeding.

Patient may present with painless bleeding with no associated symptoms or in the advanced stages of shock. There may be clues to the underlying aetiology or predisposition – for example stigmata of chronic liver disease.

Moderate bleeding

- Pyrexia

- Weight loss

- Dizziness

- Altered bowel habit

- Abdominal pain

- Haematochezia

- Perianal disease

- Melaena (consider UGI source)

Massive bleeding

- Confusion

- Dehydration

- Tachycardic and hypotensive

- Abdominal pain

- Haematochezia

Investigations & diagnosis

LGIB is a clinical diagnosis with an aetiology that may be revealed by CT scan or lower GI endoscopy.

In general, investigations help to determine the extent and location of bleeding. In some instances, they can offer both diagnostic information and haemostatic control (e.g. endoscopy).

A full blood count (FBC) and digital rectal examination (DRE) are important initial tests for assessing LGIB. Depending on the presentation, some patients may then require imaging and/or endoscopic assessment as an inpatient.

Bedside

- Digital rectal examination

- Observations

- Lying / standing blood pressure

- Blood glucose

- ECG

- Stool microscopy, culture & sensitivities

- Faecal calprotectin

Bloods

- Full blood count

- Urea & electrolytes

- Liver function tests

- Haematinics

- Clotting

- Arterial / venous blood gas

- Group and saves +/- cross-match

Imaging

- Erect CXR: to look for evidence of free air under the diaphragm indicative of hollow viscus perforation.

- CT abdomen/pelvis: CT may be ordered to identify the underlying diagnosis, e.g if a large colonic malignancy is suspected or to look for evidence of ischaemic colitis.

- CT angiography: CT angiogram may allow identification of a bleeding point – typically only in patients with brisk active bleeding.

Special

- Flexible sigmoidoscopy

- Colonoscopy

- Upper GI endoscopy (e.g. if UGIB suspected)

- Angiographic transarterial embolisation

Management

The management of lower GI bleeding is largely dependent on the clinical presentation.

Over the years studies and audits have looked at how we can best set up care to ensure good patient experience and outcomes. The NCEPOD report Time to get Control (looking at UGIB and LGIB) had a number of principal recommendations which included:

- Admitting hospital should have 24/7 access to on-site endoscopy

- Admitting hospital should have 24/7 access to interventional radiology services

- Admitting hospital should have 24/7 access to appropriate surgeons, anaesthesia and HDU/ICU

- All patients with a major GI bleed should be discussed with the named ‘bleed’ consultant within one-hour of recognition

In 2019 the British Society of Gastroenterologists (BSG) released guidelines on the Diagnosis and management of acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. The below management gives a brief overview of this.

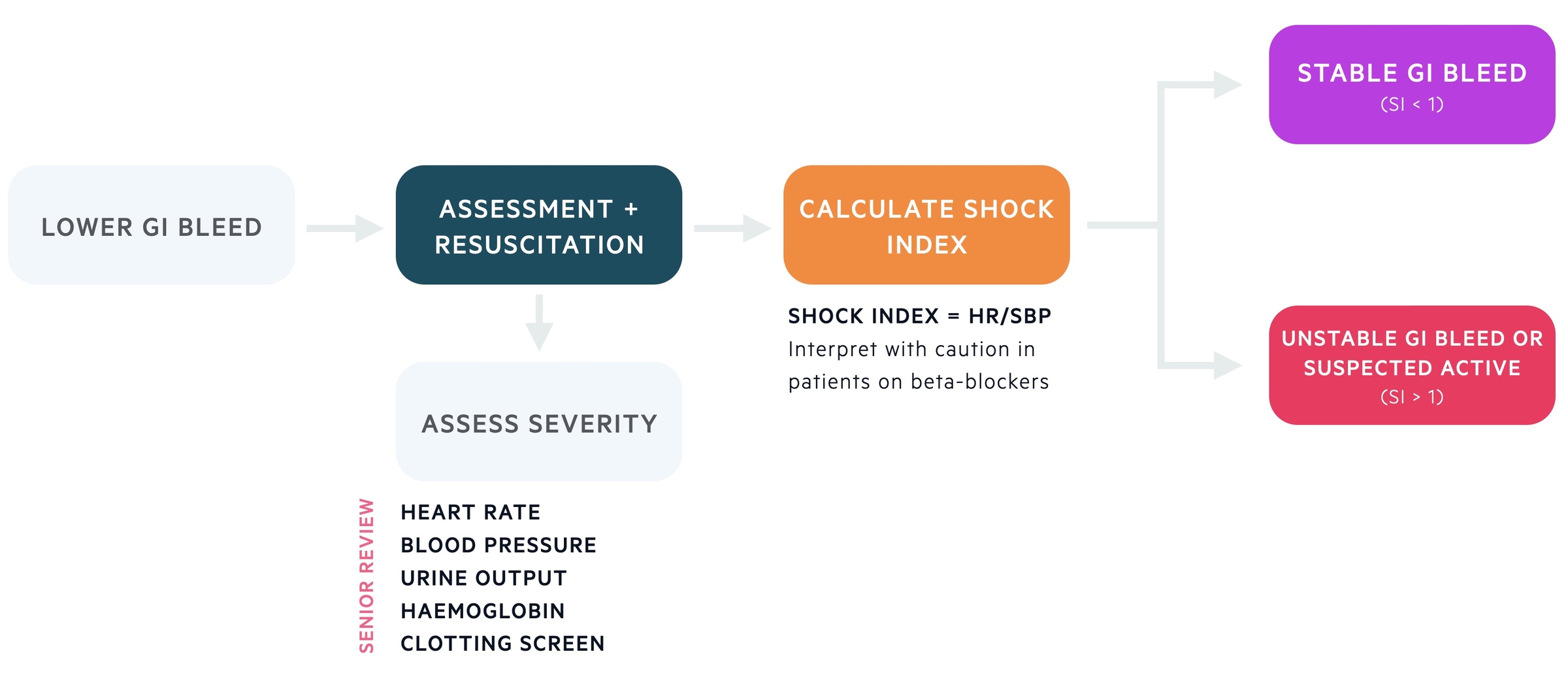

Initial assessment

The initial management is dependent of the severity of the bleed and the clinical status of the patient. Those with significant bleeds, haemodynamic instability or other causes for concern should be managed in Resus with early senior input.

Every patient should have a clinical review with resuscitation (here referring to fluids/blood transfusion) initiated simultaneously when indicated. A PR exam is a core part of the assessment. Patients can have their shock index calculated by dividing the heart rate by the systolic blood pressure (intepret with caution in those taking beta-blockers which can inhibit a normal tachycardic response). BSG define a shock index > 1 or suspected active bleeding as an unstable GI bleed.

Supportive care

Excessive and unnecessary transfusions should be avoided as each unit of packed red cells carries independent risks to morbidity and mortality. Generally a transfusion trigger of 70 g/L is advised with a post-transfusion target of 70-90 g/L. In those with cardiovascular disease a trigger of 80 g/L is typically advised with a post-transfusion target of 100 g/L.

Patients may have an underlying coagulopathy (chronic liver disease) or be on medications that lead to increased risk of bleeding. Those with unstable bleeds need reversal, though this will typically be discussed with haematology and depend on the underlying cause or drug. In those with high-thrombotic risk (e.g. metallic heart valve, recent VTE) discussion with senior members of cardiology/haematology should be had.

Stable GI bleed

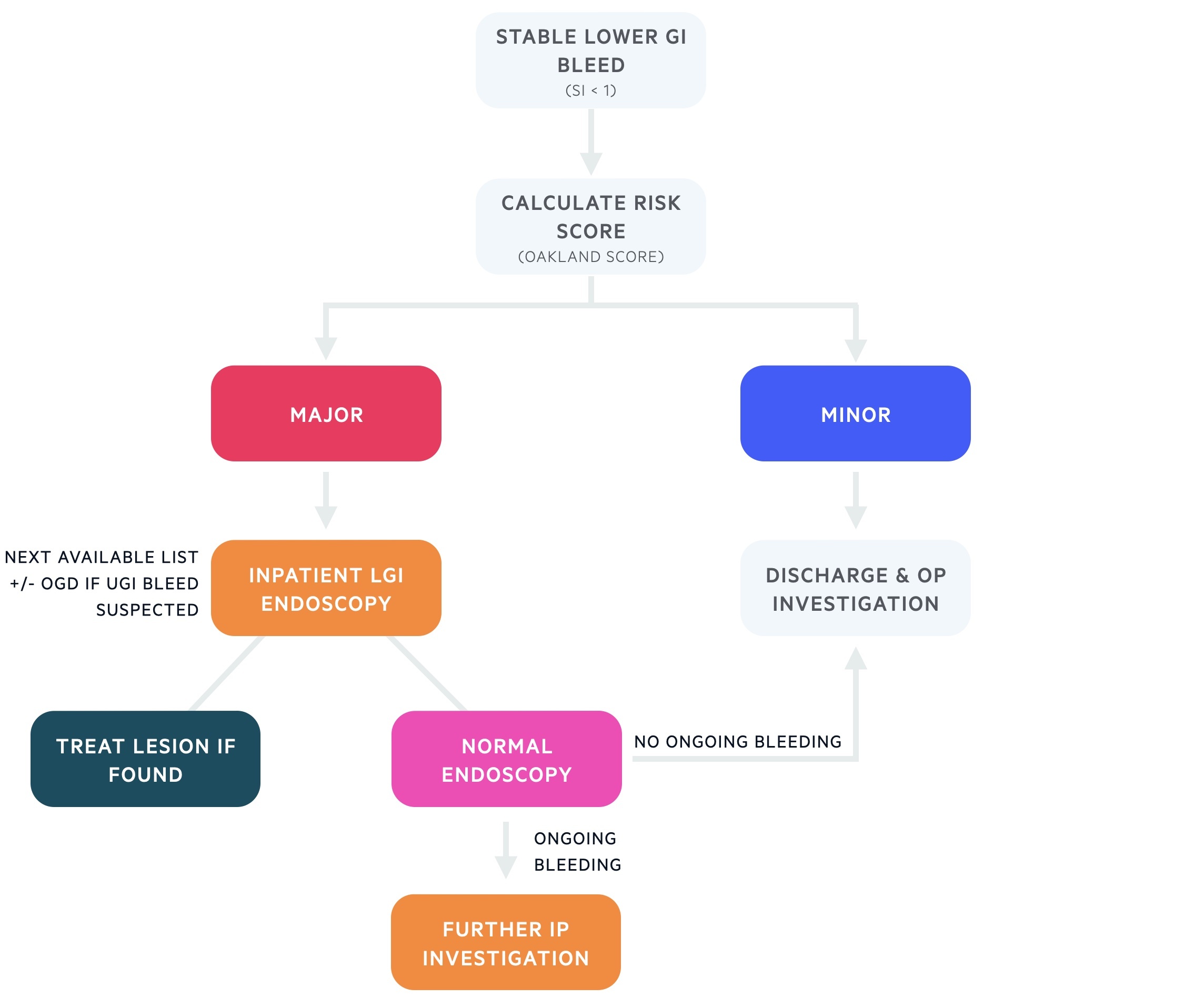

Patients may be categorised as having stable bleeds if their shock index is less than one and there is no active bleeding suspected. The Oakland score can be used to assess risk:

Minor (Oakland score ≤ 8)

Patients with minor bleeds that self terminate without haemodynamic instability or significant anaemia may be safely discharged if there is not other reason for admission. Patients are given appropriate safety netting advice and follow-up investigations.

Major (Oakland score > 8)

Those with major bleeds should be admitted for monitoring, supportive care and lower GI endoscopy (+/- upper GI endoscopy) as an inpatient. If a lesion is found on endoscopy it may be treated. If no cause is seen and there is ongoing bleeding investigations may include capsule endoscopy, CT angiogram and NM scans.

Should the clinical picture change – i.e. new active bleeding – the patient should receive a full re-assessment. Those with unstable or active bleeding should be considered for CT angiogram +/- embolisation.

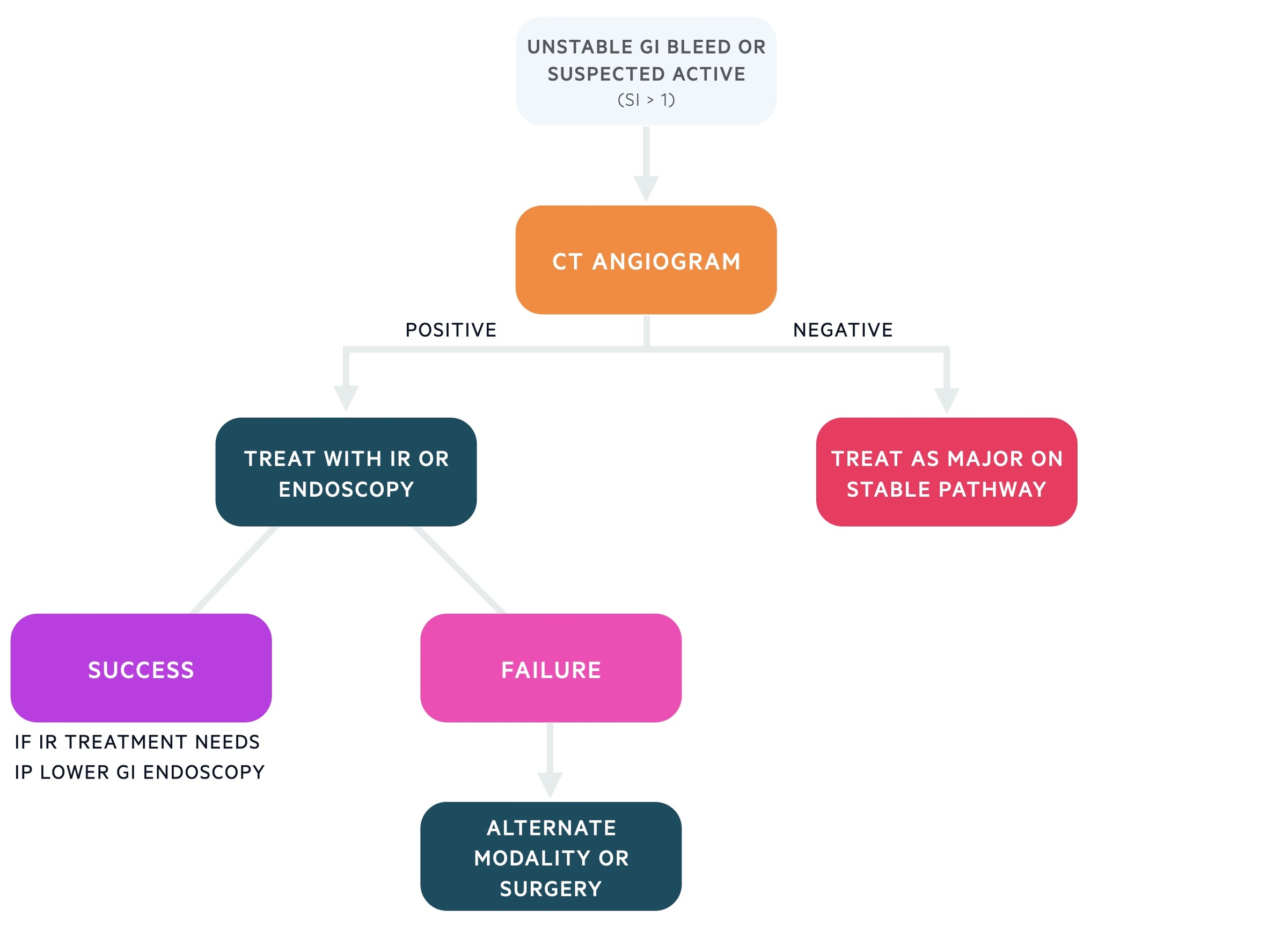

Unstable GI bleed

Patients with unstable GI bleeding (SI > 1) or suspected active bleeding should have a CT angiogram organised. This may identify an area of active bleeding (extravasation of contrast) that may be treated by interventional radiology (IR) with embolisation or with endoscopic techniques. Those with a negative CT angiogram should be managed as those on the major pathway of stable GI bleed described above.

If one modality fails to stop an identified bleeding point the other treatment option should be considered (i.e. IR and endoscopy). Rarely surgical management may be needed.

Prognosis

Patients admitted with a LGIB have an in-hospital mortality of 3.4%.

The risk of death is more closely related to a patients co-morbidities than the nature of the bleed. Mortality rises to 18% for in-patient LGIBs and 20% if 4 or more units of red cells are required.