Introduction

Cushing’s syndrome is caused by prolonged exposure to an excess of glucocorticoids.

Clinical features depend on the duration of disease and degree of cortisol excess but include weight gain, skin changes, menstrual irregularities, glucose intolerance and mood disturbance.

The cause may be endogenous or exogenous:

- Exogenous: i.e. derived externally – occurs due to the administration of glucocorticoids either as a medication or misuse. This is by far the most common cause.

- Endogenous: i.e. derived internally – occurs due to excess production of glucocorticoids by the body itself. This is very rare (estimated at 5 in 1,000,000). Cushing’s disease, which refers to cases caused by a pituitary adenoma, is responsible for the majority of endogenous cases.

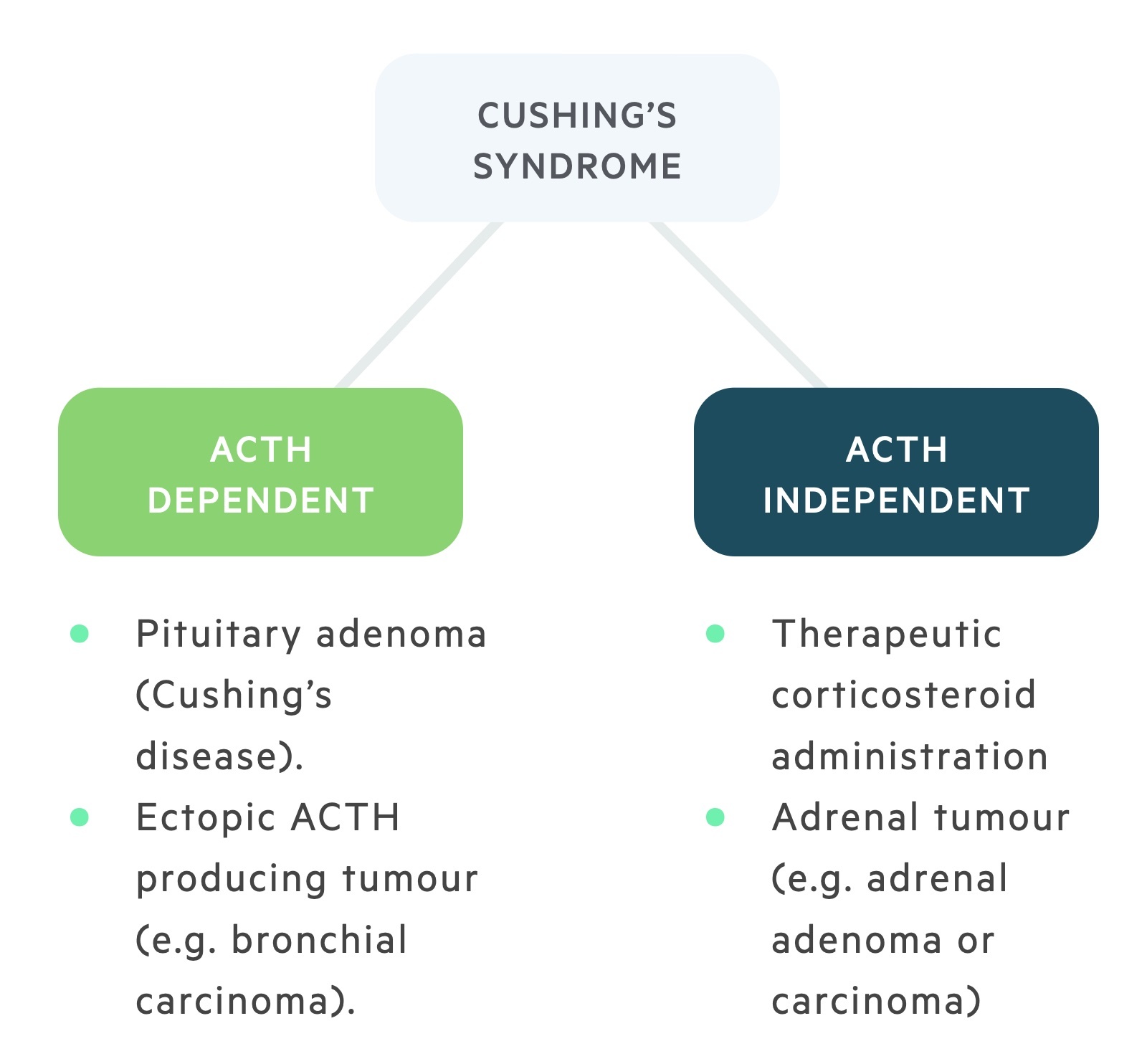

Cushing’s syndrome is defined based upon its aetiology – whether the cortisol excess is ACTH dependent or independent:

- ACTH dependent: cortisol excess is driven by ACTH, either from the pituitary or ectopic sources.

- ACTH independent: cortisol excess is independent of ACTH. Includes exogenous causes (consumption of cortisol) and adrenal lesions (adenomas, carcinomas).

Physiology

Cortisol secretion is controlled by the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis.

1. Corticotropin-releasing hormone

Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) is released by the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. It is transported via the hypophyseal portal system to the anterior pituitary where it stimulates the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH).

2. Adrenocorticotropic hormone

ACTH, released from the corticotrophs of the anterior pituitary, stimulates the release of cortisol.

The precursor of ACTH is POMC, this is also the precursor of beta-melanocyte-stimulating hormone. In addition, ACTH may be cleaved to form alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone. As a result ACTH excess results in hyperpigmentation (resulting from melanocyte stimulation), particularly affecting the oral mucosa and palmar creases.

ACTH excess is a feature of both Addison’s disease (primary adrenocortical insufficiency) and ACTH dependent Cushing’s syndrome.

3. Cortisol

Cortisol is released from the adrenal cortex in response to ACTH. It exerts negative feedback on the release of both ACTH and CRH.

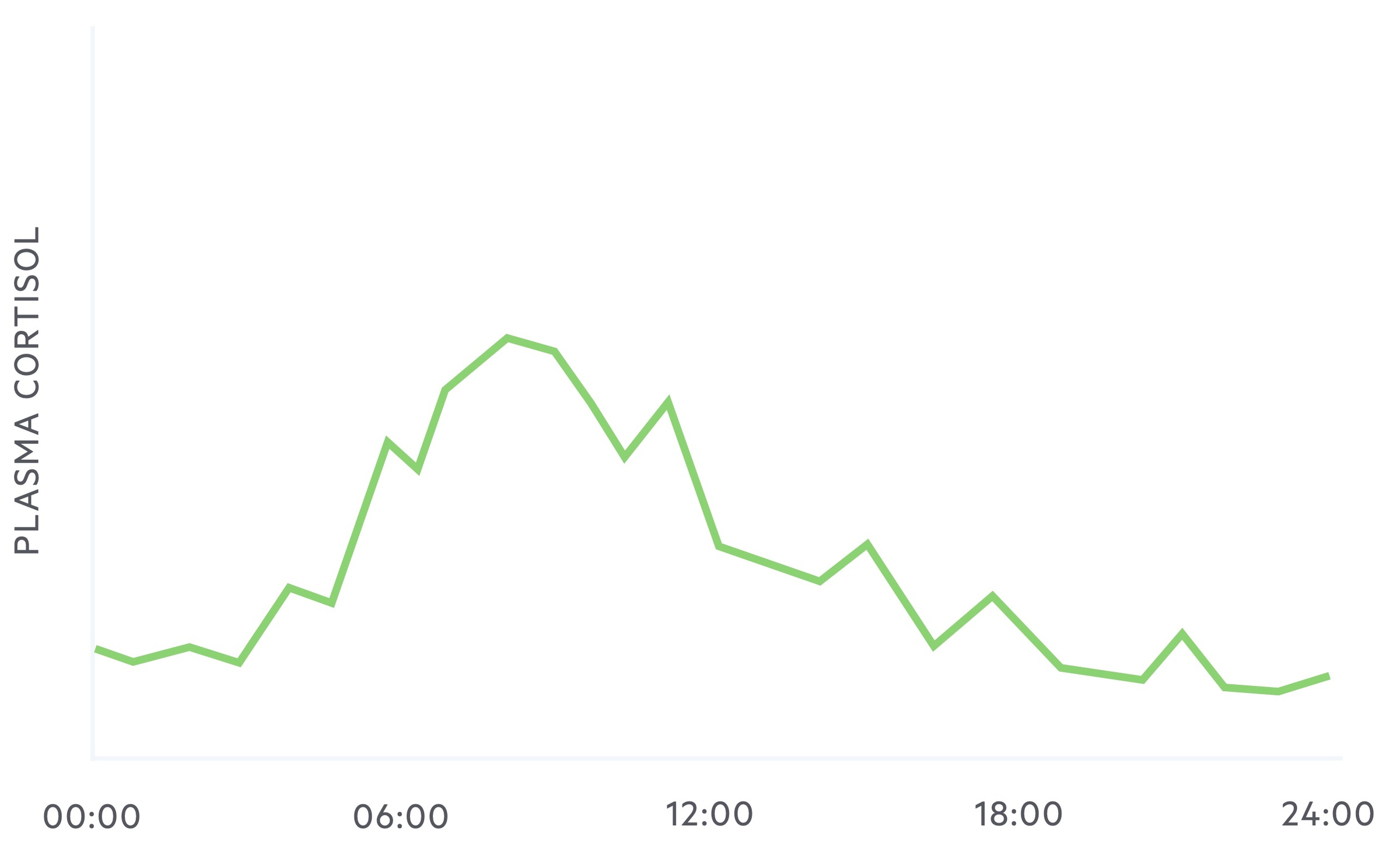

Cortisol exhibits diurnal variation, that is to say, the plasma concentration of cortisol levels vary during a 24 hour period.

It reaches a zenith (highest point) at around 8 am and a nadir (lowest point) at around midnight to 1 am.

Aetiology

The causes of Cushing’s may be divided into those that are ACTH dependent and those that are ACTH independent.

ACTH dependent

ACTH dependent Cushing’s occurs due to the excess production of ACTH. When exogenous causes are excluded, ACTH dependent causes are responsible for 80% of all Cushing’s syndrome.

There are a number of causes:

- Cushing’s disease: The most common non-exogenous cause, this refers to Cushing’s syndrome caused by a pituitary adenoma that results in corticotrophs releasing excess ACTH.

- Ectopic ACTH production: This may be seen as a paraneoplastic syndrome in lung cancers where malignant cells produce ACTH and are not subject to normal negative feedback mechanisms.

- Ectopic CRH production: Rarely CRH may be produced by malignant tissue resulting in increased ACTH and cortisol production.

The pituitary adenoma seen in Cushing’s disease is less responsive to glucocorticoid negative feedback but will respond at high levels – as such a high dose dexamethasone suppression test (see ‘Identifying a cause’ below) can be used to distinguish a pituitary adenoma from ectopic ACTH sources.

ACTH independent

ACTH independent Cushing’s occurs in the presence of normal ACTH production. There are a number of causes:

- Endogenous administration: Prolonged exposure to exogenous glucocorticoids is the most common cause of Cushing’s syndrome. Results in suppression of CRH and ACTH.

- Primary adrenal lesions: tumours (adenomas, carcinomas and hyperplasia) may result in cortisol excess and suppression of CRH and ACTH.

- Other: Very rare causes include bilateral macronodular adrenal hyperplasia and primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease.

Clinical features

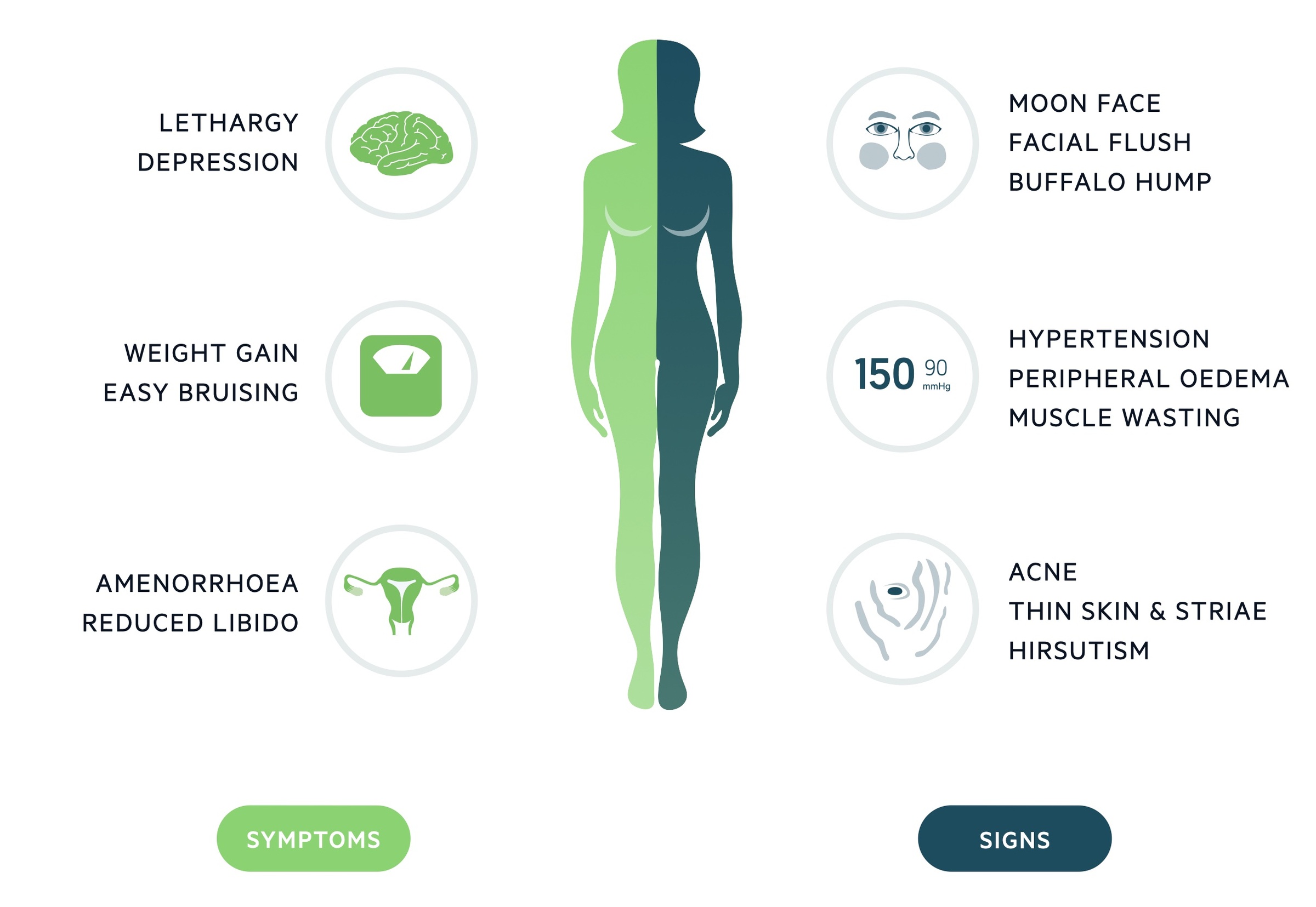

The clinical features asssociated with Cushing’s syndrome are related to the effects of excess cortisol.

Symptoms

- Tiredness

- Depression

- Weight gain

- Easy bruising

- Amenorrhoea

- Reduced libido

- Striae

Signs

- Acne

- Moon facies

- Plethora

- Buffalo hump

- Hypertension

- Proximal muscle weakness

- Hyperpigmentation (in ACTH dependent causes)*

* NOTE: The precursor of ACTH is POMC, this is also the precursor of beta-melanocyte-stimulating hormone. In addition, ACTH may be cleaved to form alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone. As a result ACTH excess results in hyperpigmentation due to melanocyte stimulation). This is particularly noted on the oral mucosa and palmar creases.

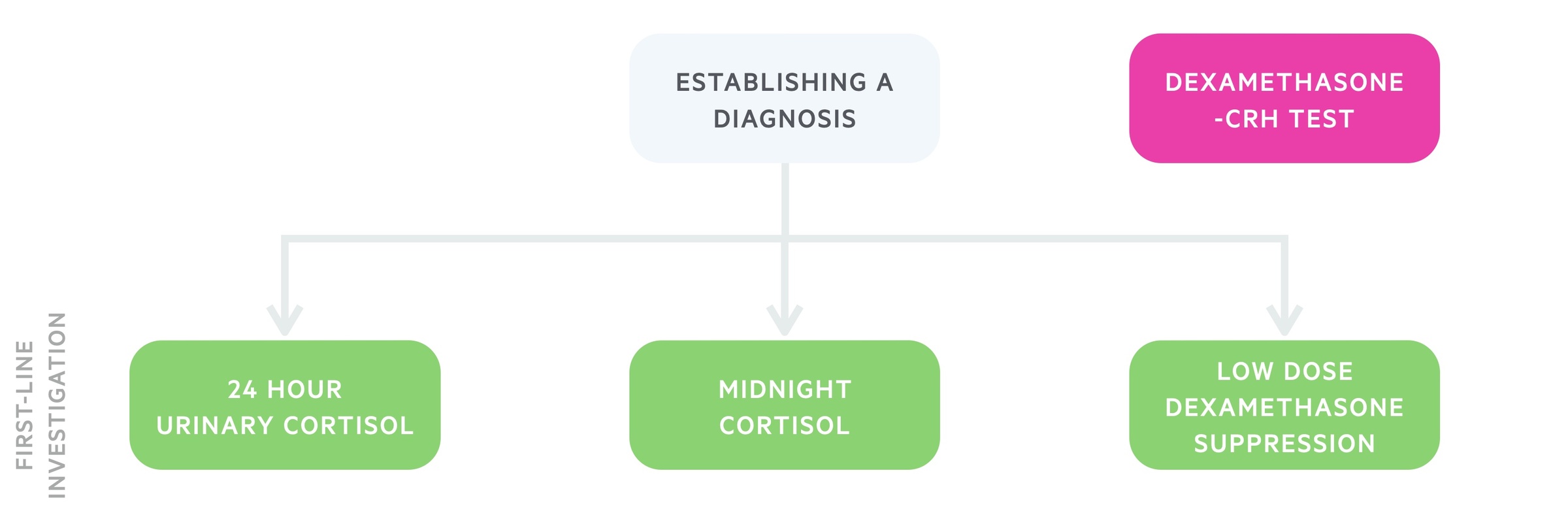

Establishing a diagnosis

The work-up for Cushing’s syndrome follows two stages, establishing a diagnosis and establishing a cause.

There are a number of diagnostic tests that can be arranged that either aim to demonstrate excess cortisol production or abnormal hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis function. Of course, the below tests are for endogenous causes – in exogenous disease, there should be a clear history of prolonged glucocorticoid use.

24-hour urinary cortisol

A 24-hour urinary cortisol is often the initial test in a patient with suspected Cushing’s syndrome. Three or more collections are usually needed. Levels 3-4x normal are highly suggestive of Cushing’s syndrome.

Importantly, creatinine levels also need to be measured as the variation in levels between samples (>10 %) indicates that the test needs to be repeated.

Midnight cortisol

Taking midnight cortisol levels helps to demonstrate a loss of the normal circadian pattern.

Cortisol levels can be salivary or blood-based. If blood, samples should ideally be taken from an indwelling cannula, which helps minimise stress.

Low-dose dexamethasone suppression

1 mg of dexamethasone is given at 11 pm and serum cortisol is then measured at 8 am. In a normal individual, the administration of dexamethasone should suppress the morning rise in serum cortisol. However, in patients with Cushing’s syndrome, there is a lack of suppression, which warrants further investigation.

Dexamethasone-CRH test

This test is less commonly used, dexamethasone is given for a period, followed by the administration of CRH. Serum cortisol (and ACTH) levels can then be measured. It may help distinguish between Cushing’s and hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis dysregulation seen in severe depression.

Identifying a cause

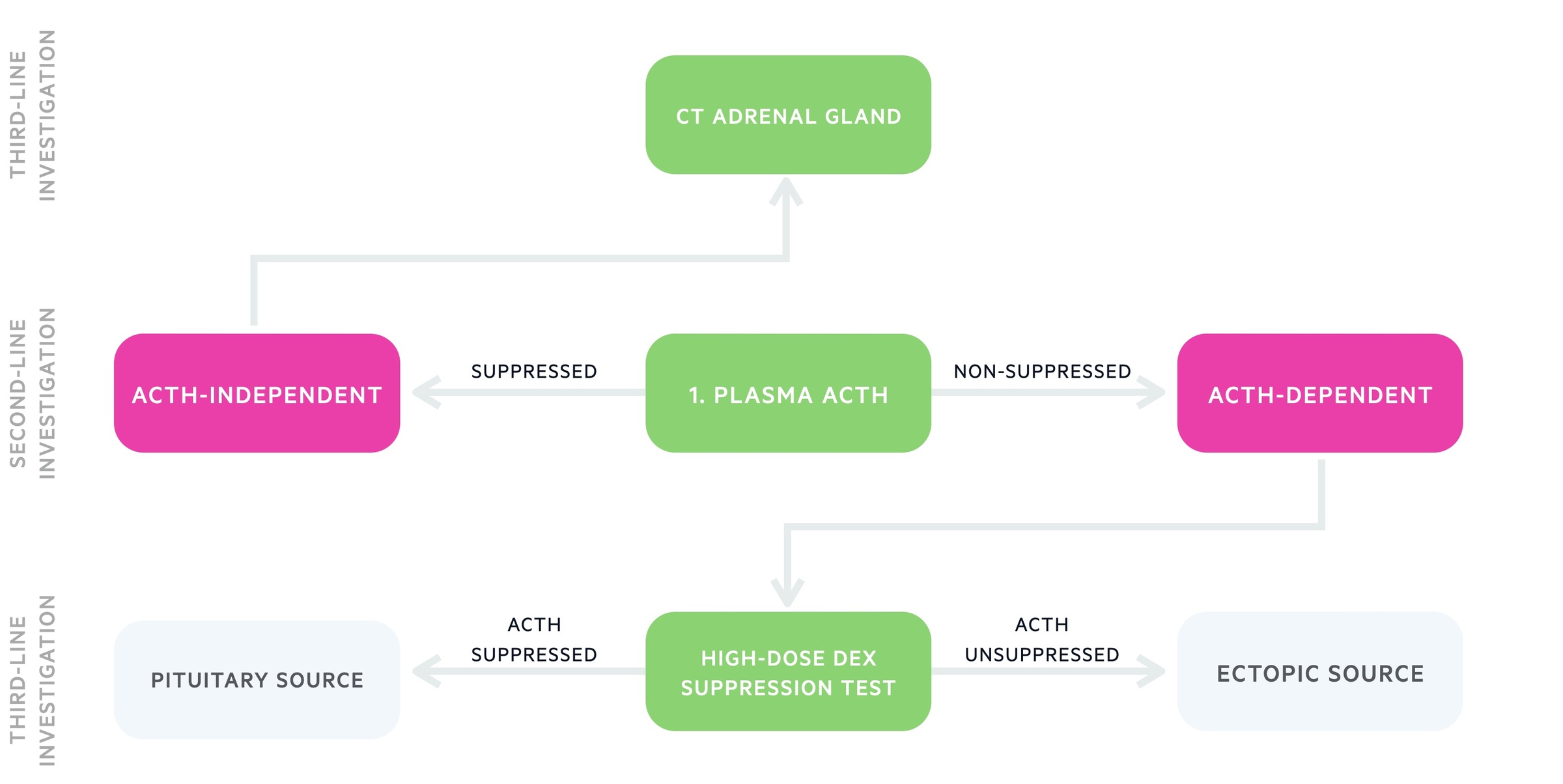

After diagnosing cortisol excess we must identify the underlying aetiology.

Plasma ACTH

Plasma ACTH is the first test conducted when attempting to establish the cause of Cushing’s syndrome:

- Suppressed / undetectable ACTH: Indicative of an ACTH independent cause of Cushing’s syndrome.

- Raised / inappropriately normal ACTH: Suggestive of an ACTH dependent cause.

Once a decision has been made as to whether the disease is or isn’t ACTH dependent further investigations can be ordered.

ACTH independent

The vast majority of non-exogenous ACTH independent Cushing’s is caused by adrenal pathology. As such in patients with suspected ACTH independent Cushing’s syndrome a CT of the adrenal glands is normally the first line investigation. Further tests may include MRI adrenal glands and PET/CT.

ACTH dependent

The high-dose dexamethasone suppression test helps to determine, in ACTH dependent causes:

- Pituitary adenomas (Cushing’s disease): High levels of dexamethasone are able to suppress ACTH production.

- Ectopic production: Despite high dose dexamethasone, ectopic tissues will not be suppressed and continue to produce ACTH.

Other tests may then be arranged to identify the pituitary adenoma or look a malignancy responsible for ectopic production – this will typically involve CTs and MRIs.

Petrosal sinus sampling is an invasive test that may be used to help identify a microscopic pituitary adenoma. A catheter is passed into the petrosal sinuses that surrounds the pituitary gland and the level of ACTH (+/- CRH stimulation) can be assessed. This can be compared to levels from a peripheral vein. Petrosal sinus sampling may be used to identify the side of the tumour.

Exogenous management

The management of exogenous Cushing’s is the withdrawal of the glucocorticoid.

Patients who have developed Cushing’s from exogenous steroid use should not abruptly stop. They will likely have developed suppression of their normal endogenous glucocorticoid production – as such stopping could result in an addisonian crisis.

Instead the patient should have a gradual tapering regimen with close safety netting and monitoring.

Cushing’s disease management

Transsphenoidal surgery is the gold-standard for treatment of Cushing’s disease.

Surgical

Cushing’s disease is typically treated with transsphenoidal surgery, with either:

- Microadenomectomy: where an identifiable adenoma is found this can be resected leaving residual tissue of the anterior pituitary

- Subtotal resection of the anterior pituitary: used where no identifiable adenoma and no desire for fertility after counselling the patient. There is a risk of hypopituitarism.

Medical

Medical therapy is most commonly used as a bridge to definitive surgical management or in the case that surgery is not possible or fails.

Metyrapone can be used, an inhibitor of 11β-hydroxylase, that leads to a reduction in cortisol synthesis.

Pituitary irradiation

This may be used in children and young people or those in whom surgical techniques have failed. Effects are not immediate and takes around 6-12 months to have maximal effect.

Adrenalectomy

In those in who all other therapies have failed bilateral adrenalectomy may be used. This mandates lifelong glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid replacement.

Management of adrenal lesions

Adrenal lesions may be treated with surgical resection.

Unilateral adrenal adenoma

Unilateral adrenalectomy offers curative therapy. Where available the laparoscopic approach is generally preferred to open surgery. Following surgery patients will need a tapering course of exogenous steroids for a period of time as their endogenous CRH and ACTH will be suppressed.

Bilateral adrenal hyperplasia

In patients with overt Cushing’s bilateral adrenalectomy may be offered. Following this patients require replacement of glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids.

Adrenal carcinoma

Following appropriate staging resection is the mainstay of management. Adjuvant chemotherapy, radiotherapy or mitotane may be given.