Introduction

Cardiac murmurs refer to sounds caused by turbulent blood flow.

Murmurs are a common finding in clinical practice. They can help to identify underlying cardiac disease, and as such are often examined in clinical OSCEs.

To accurately identify and characterise murmurs, a good understanding of the underlying physiological and pathological processes is needed as well as clinical experience.

In this note, we give an overview of cardiac auscultation and some common causes of murmurs.

Auscultation

Cardiac auscultation is a key part of any cardiovascular examination.

It takes a great deal of practice to perform a smooth and complete cardiovascular exam. Auscultation is a key component and perhaps the hardest to master. To become truly adept takes a great deal of time and practice, hearing both normal and pathological sounds.

A traditional stethoscope has two sides:

- Bell: best for low pitched sounds

- Diaphragm: best for high pitched sounds

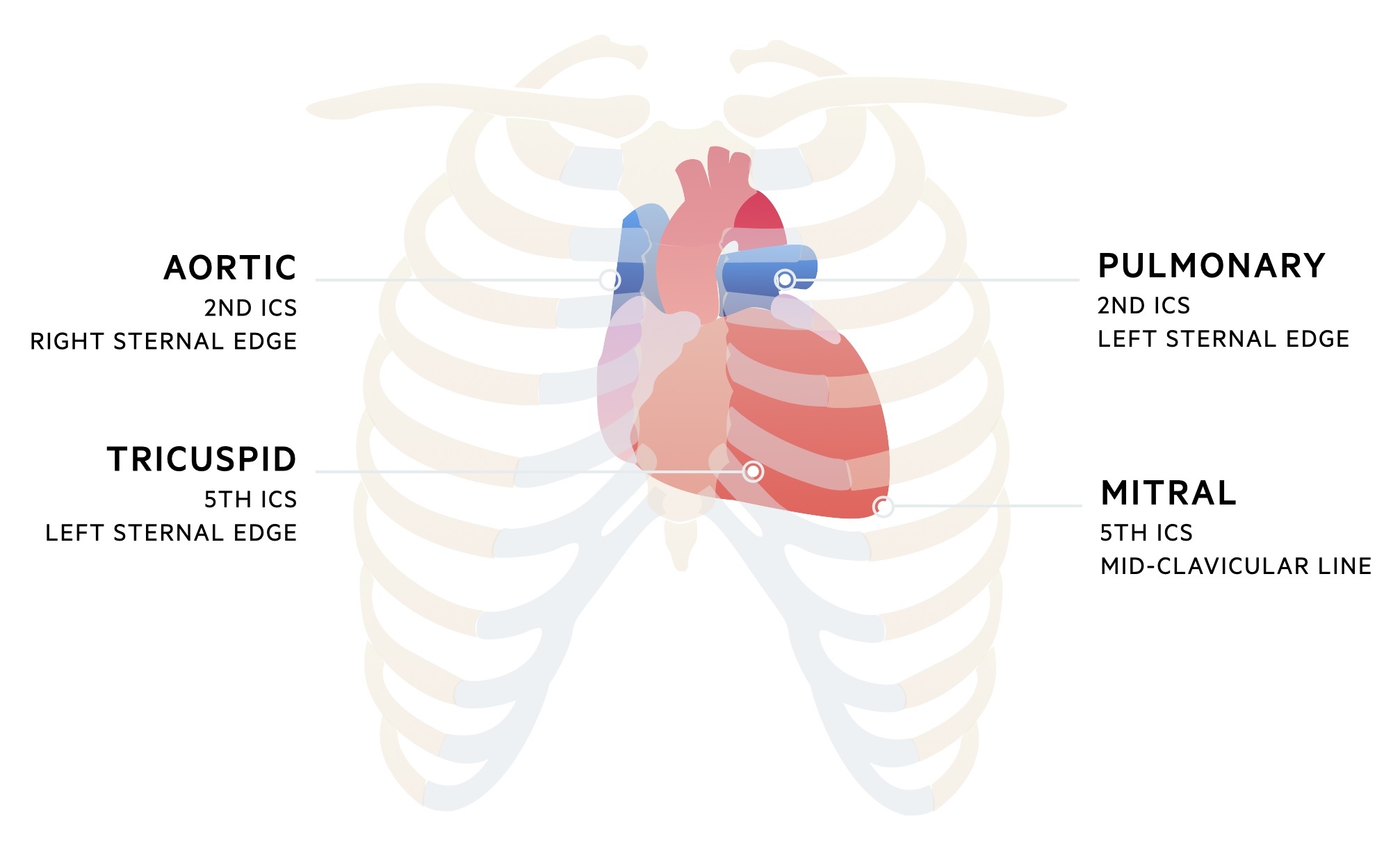

Where to listen

There are four areas that are considered standard to auscultate as part of any cardiovascular exam. These correspond with the best area to auscultate each valve (not necessarily their anatomical location):

- Aortic: best heard in the second intercostal space at the right sternal edge

- Pulmonary: best heard in the second intercostal space at the left sternal edge

- Mitral: best heard in the fifth intercostal space on the left mid-clavicular line

- Tricuspid: best heard at the fifth intercostal space at the left sternal edge

Begin by auscultating each area with the diaphragm of the stethoscope and then repeat with the bell of the stethoscope. Alternatively, alternate between the two at each area. The carotid pulse can be palpated on one side whilst listening to the heart to aid with the identification of S1 (it occurs at the same time as the carotid pulsation).

Additional areas may be focused on depending on the underlying suspected pathology. For example, the murmur of aortic stenosis may be heard to radiate to the carotids whilst mitral regurgitation may radiate to the axilla.

Position

During the majority of the examination, the patient should be positioned on a couch with the head of the bed angled at 45 degrees.

After auscultating the four areas described above, carry out the following position changes (in those who can tolerate them) to accentuate murmurs:

- Aortic regurgitation: ask the patient to sit up and lean forward whilst listening at the left sternal edge.

- Mitral stenosis: ask the patient to lie on their left side and listen at the apex with the bell of the stethoscope.

Dynamic manoeuvres

Dynamic manoeuvres can help to identify murmurs:

- Valsalva: during the Valsalva manoeuvre cardiac output falls and murmurs tend to soften. At its release, murmurs of HOCM and mitral insufficiency can be heard to get louder.

- Respiration: right-sided murmurs tend to be louder on inspiration, left-sided murmurs tend to be louder on expiration. This can be remembered with R-I-L-E (right on inspiration, left on expiration).

Heart sounds

Healthy adults will typically have two hearts sounds termed S1 and S2.

The sounds are often described as ‘lubb (S1) dub (S2)’. The are caused by the closure of the atrioventricular and semilunar valves during the cardiac cycle.

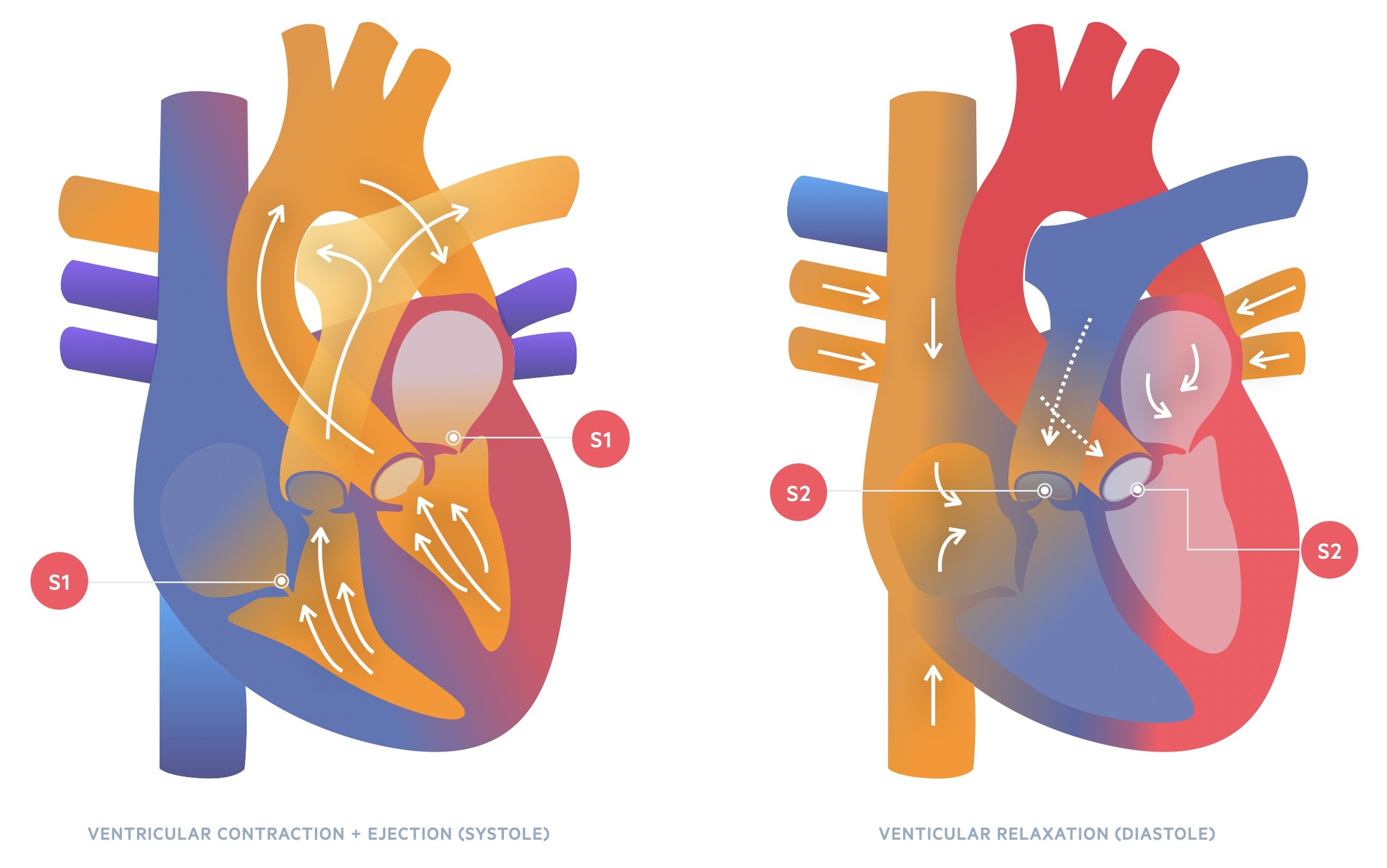

S1

The first heart sound, S1, is made by the closure of the atrioventricular valves (the mitral and tricuspid valves). Their closure is prompted by the beginning of ventricular systole which forces these valves closed.

On auscultation, S1 is said to be heard best at the apex of the heart.

S2

The second heart sound, S2, is made by the closure of the semilunar valves (the pulmonary and aortic valves). Their closure is prompted by ventricular diastole allowing the pressure differential with the great vessels to force the valves closed.

Typically the pulmonary valve closes just after the aortic valve as right ventricular ejection lasts slightly longer. This is accentuated during inspiration where increased venous return (intra-thoracic pressure drops during inspiration drawing blood in) results in prolongation of right ventricular ejection. S2 may be heard to be ‘split’ into A2 and P2 components – a finding that is referred to as physiological splitting.

Abnormal splitting may be indicative of disease:

- Single S2/Reversed split: seen in aortic stenosis

- Fixed splitting: seen in atrial septal defects

- Exaggerated splitting: seen in pulmonary stenosis, ventricular septal defect, mitral regurgitation

S3

A third heart sound, S3, may be heard in healthy children and young adults. It is a sound heard in early diastole due to rapid ventricular filling. In older patients, it may be a sign of heart failure.

S4

A fourth heart sound, S4, may be heard in otherwise healthy older patients. It is a sound heard in late diastole due to rapid ventricular filling during atrial systole. It can represent a non-compliant ventricle that may be due to pathologies like hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and aortic stenosis.

Additional sounds

- Ejection click: seen in aortic stenosis, due to the opening of the valve early in systole.

- Systolic click: seen in mitral valve prolapse, due to tensing of chordae tendineae as the valve prolapses in mid-systole.

- Opening snap: seen in mitral stenosis, caused by opening of the stenotic valve in early diastole.

Characterising murmurs

Murmurs are sounds caused by turbulent blood flow.

Murmurs can represent valvular pathology or be physiological. Identifying the origin of a murmur can be challenging. Though we have increasingly easy access to transthoracic echocardiography it is important to try to correctly identify a murmur clinically. There are a number of things to consider to help this process:

- Its timing in the cardiac cycle

- Its character and grade (see below)

- Where it is heard loudest

- Pitch – is it best heard with the bell or diaphragm

- Change with position or dynamic manoeuvres

- Radiation (e.g. into the carotids)

The Levine scale can be used to grade murmurs:

- Grade 1: very quiet, heard by experts

- Grade 2: slight murmur, should be heard by most examiners

- Grade 3: moderate, easily heard, no palpable thrill

- Grade 4: loud, palpable thrill

- Grade 5: very loud, palpable thrill

- Grade 6: can be heard without a stethoscope

It is very rare for a diastolic murmur to be grade 5 or above and as such, they are typically graded 1-4.

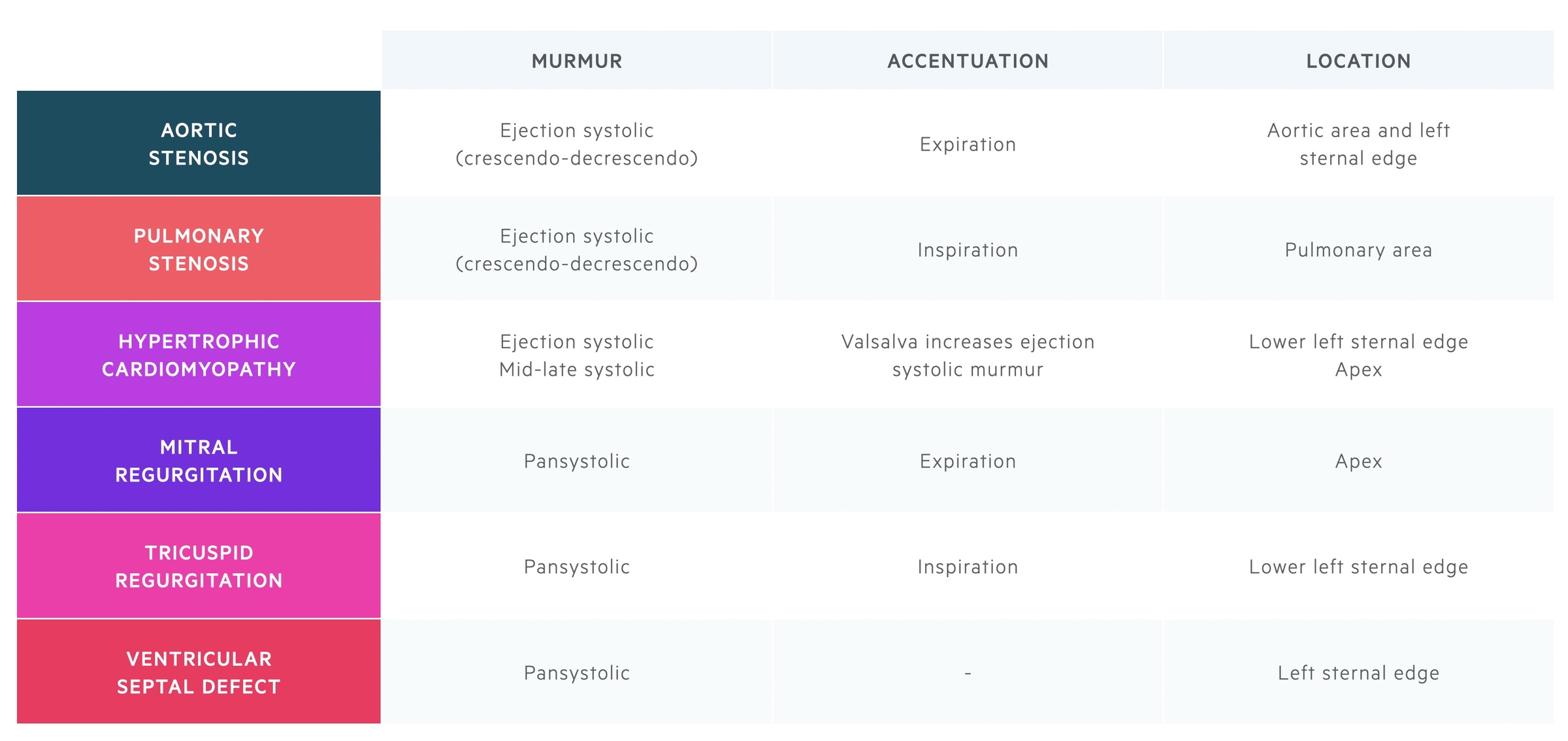

Systolic murmurs

Systolic murmurs are often described as ejection systolic (e.g. in aortic stenosis) or pansystolic (e.g. mitral regurgitation).

Systolic murmurs may occur during any part of systole. Here we describe some of the most common (and commonly examined) systolic murmurs.

It is important to note that murmurs are not necessarily exactly the same amongst different patients with the same pathology. The murmur and additional signs of each of these conditions are somewhat dependent on the severity of the pathology (e.g. the degree of stenosis) and the presence of associated pathologies or changes that occur secondary to the pathology itself (e.g. left ventricular hypertrophy occurring secondary to aortic stenosis). This is as true of conditions causing diastolic murmurs, which are discussed in the chapter below, as it is of systolic murmurs.

Aortic stenosis

Aortic stenosis is a common valvular pathology affecting 2-7% over the age of 65. It is characterised by an ejection systolic ‘woosh’ that is often one of the easiest murmurs to identify as a medical student – as such it often comes up in OSCEs!

Aetiology: calcific (most common), bicuspid (congenital), rheumatic heart disease (common in the developing world)

Symptoms: syncope, angina, dyspnea (SAD)

Murmur: ejection systolic, described as crescendo-decrescendo. Radiates to the carotids.

Best heard: on expiration in the aortic area.

Additional signs:

- Sustained apex

- Slow rising pulse

- Narrow pulse pressure

- Heart sounds:

- Soft S2 (sign of severe disease)

- S4

- Reversed splitting of S2

For more detail check out our notes on Aortic stenosis.

Pulmonary stenosis

Pulmonary stenosis is often seen as a component of congenital syndromes but may also be acquired later in life. Similar to aortic stenosis it results in an ejection systolic murmur.

Congenital associations: Noonan syndrome, tetralogy of Fallot, congenital rubella syndrome

Acquired causes: carcinoid syndrome, rheumatic fever

Symptoms: syncope, fatigue

Murmur: ejection systolic, described as crescendo-decrescendo. Often associated with a thrill.

Best heard: on inspiration at the pulmonary area.

Additional signs:

- Right ventricular heave

- S4

- Prominent a waves

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

HOCM refers to a collection of inherited conditions that result in myocardial hypertrophy. It may be picked up incidentally, on family screening, symptomatically or present with sudden cardiac death (most common cause of sudden cardiac death in young people).

Its ejection systolic murmur is caused by left ventricular outflow obstruction. Its mid-late systolic murmur is secondary to systolic anterior motion or ‘SAM’ of the mitral valve, this tends to radiate to the axilla.

Aetiology: mutation of β-myosin heavy chain or myosin-binding protein C are the most common causes.

Symptoms: chest pain, dyspnea, syncope, arrhythmia. May present with sudden death.

Murmur: ejection systolic murmur, mid-late systolic murmur.

Best heard: the ejection systolic murmur is best heard at the lower left sternal edge. The mid-late systolic murmur is often best heard at the apex and may radiate to the axilla.

Dynamic manoeuvres: ejection systolic murmur intensity increased by Valsalva or standing (decreases afterload).

Additional signs:

- Jerky carotid pulse

- Double apical pulsation

- S4

- Arrhythmia (e.g. AF)

Mitral regurgitation

Mitral regurgitation refers to incompetence of the valve that may occur due to abnormalities to the valve leaflets, subvalvular apparatus or left ventricle. It may be acute or chronic.

Aetiology: degenerative, infective endocarditis, rheumatic heart disease, congenital abnormalities, medications (e.g. ergotamine)

Symptoms of acute MR: rapid development of heart failure, flash pulmonary oedema

Symptoms of chronic MR: dyspnoea, orthopnoea

Murmur: pansystolic murmur

Best heard: over the apex. Depending on the direction of the regurgitant jet, may radiate to the axilla.

Additional signs:

- Soft S1

- S3

- Mid-systolic click (in valve prolapse due to tensing of chordae tendineae)

For more detail check out our notes on Mitral regurgitation.

Tricuspid regurgitation

Tricuspid regurgitation refers to incompetence of the tricuspid valve. It may be primary (i.e. disease directly affects the valve and its apparatus) or secondary (i.e. caused by dilatation of the right ventricle). In adults most cases are secondary (also termed functional) in nature.

Aetiology of primary TR: rheumatic heart disease, carcinoid syndrome, infective endocarditis, Ebstein’s anomaly.

Aetiology of secondary TR: any cause of pulmonary hypertension and secondary dilation of the right ventricle.

Symptoms: fatigue, dyspnea, peripheral oedema, hepatomegaly

Murmur: pansystolic

Best heard: on inspiration at the lower left sternal edge, may be more lateral if right ventricle very enlarged.

Additional signs:

- Prominent, pulsatile JVP

- Large cv wave in JVP

- S3/S4

- Liver may be enlarged and pulsatile

Ventricular septal defect

Ventral septal defects (VSD) are common congenital cardiac malformations affecting around 1 in 500 births. The size of the defect and the resulting ‘shunt’ (abnormal connection and flow of blood between pulmonary and systemic circulation) determines the clinical features. It may be ‘isolated’ or seen in conjunction with other cardiac malformations.

It causes a pansystolic murmur due to blood shunting from left to right during systole. In larger defects, changes to the right side of the heart secondary to elevated pressures can lead to a softening of the murmur as pressures equalise. Reversal of the shunt, Eisenmenger’s syndrome, converts it to a cyanotic heart defect.

Aetiology: largely unknown, some cases are associated with chromosomal abnormalities (trisomy 13, 18 and 21).

Symptoms: dyspnea, fatigue, Eisenmenger’s syndrome (development of a right to left shunt due to rising right-sided pressures resulting in cyanosis)

Murmur: pansystolic

Best heard: depends on age and size of defect, generally the left sternal edge

Additional signs: there are a wide range of signs that may be present. This includes signs of heart failure and/or Eisenmenger’s syndrome. These are highly dependent on the size of the defect, direction of the shunt and other cardiac abnormalities associated with or secondary to the VSD.

Physiological murmur

Ejection type systolic murmurs are common in otherwise healthy individuals. There are thought to be a number of causes including vibration of the pulmonary trunks. They can be hard to distinguish from other causes of systolic murmurs but the remainder of the examination should be entirely unremarkable. A transthoracic echocardiogram may be used to exclude cardiac pathology.

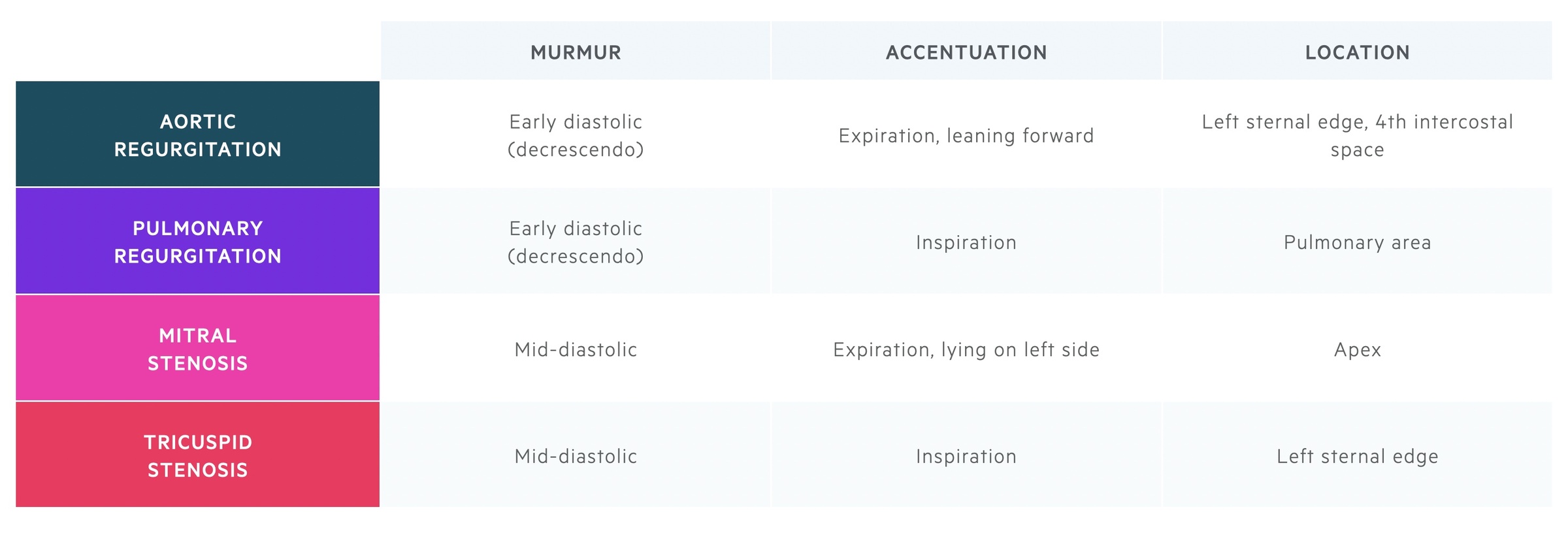

Diastolic murmurs

Diastolic murmurs are often described as early diastolic (e.g. in aortic regurgitation) or mid-diastolic (e.g. mitral stenosis).

Aortic regurgitation

Aortic regurgitation (AR) results from an incompetent aortic valve causing regurgitant flow of blood in diastole. This leads to a murmur in early diastole. It is typically considered as either acute or chronic depending on its presentation.

Aetiology of acute AR: infective endocarditis, aortic dissection, acute rheumatic fever

Aetiology of chronic AR: rheumatic heart disease, bicuspid aortic valve, connective tissue disorders, arthritides

Symptoms: dyspnea, angina, palpitations

Murmur: early diastolic

Best heard: on expiration with the patient leaning forward, at the left sternal edge, fourth intercostal space.

Additional signs:

- Displaced apex (chronic)

- Soft S1

- S2 may be soft

- Signs of heart failure

- The eponymous signs of AR (see link below)

For more detail see our notes on Aortic regurgitation.

Pulmonary regurgitation

Pulmonary regurgitation (PR) results from an incompetent pulmonary valve causing regurgitant flow of blood in diastole. This leads to a murmur in early diastole. Mild PR is quite common and typically entirely asymptomatic. With more significant regurgitation, right ventricular dilatation, secondary tricuspid regurgitation (TR) and heart failure may result.

Aetiology: physiological, infective endocarditis, carcinoid syndrome, iatrogenic, pulmonary artery dilatation.

Symptoms: if right-sided heart failure develops, peripheral oedema, fatigue and arrhythmias may result.

Murmur: early diastolic

Best heard: on inspiration in the pulmonary area.

Additional signs:

- Secondary TR:

- Peripheral oedema

- Hepatic congestion

Mitral stenosis

Mitral stenosis (MS) is characterised by valvular obstruction to flow from the left atrium to the left ventricle. This leads to a murmur typically described as a low-pitched mid-diastolic rumble.

Aetiology: rheumatic heart disease (most common), congenital MS, mitral annular calcification, radiation-associated MS, carcinoid syndrome

Symptoms: dyspnea, chest pain, haemoptysis

Murmur: mid-diastolic

Best heard: at the apex with breath held in expiration, with the patient lying on their left side. It is best heard with the bell of the stethoscope.

Additional signs:

- Mitral facies

- Pulmonary hypertension:

- Right ventricular heave

- Prominent a-wave

- Right heart failure:

- Raised JVP

- Peripheral oedema

- Hepatomegaly

For more detail see our notes on Mitral stenosis.

Tricuspid stenosis

Tricuspid stenosis (TS) is characterised by valvular obstruction to flow from the right atrium to the right ventricle. TS is relatively rare and when it occurs it is normally associated with other valvular pathologies.

Aetiology: rheumatic heart disease, carcinoid syndrome, infective endocarditis

Symptoms: peripheral oedema, ascites, dyspnea, abdominal discomfort (secondary to hepatic congestion)

Murmur: mid-diastolic

Best heard: left sternal edge on inspiration

Additional signs:

- Irregular pulse (AF)

- Prominent a-wave (if in sinus rhythm)

- Hepatomegaly

- Peripheral oedema

Eponymous diastolic murmurs

Austin-Flint murmur: is a mid-diastolic rumble seen in severe aortic regurgitation. Its exact aetiology is still debated, but it may be related to vibration of the mitral valve secondary to the regurgitant jet.

Graham-Steele murmur: an early diastolic murmur seen in pulmonary regurgitation that occurs secondary to pulmonary hypertension caused by mitral stenosis.