Overview

Mitral stenosis (MS) is characterised by valvular obstruction to flow from the left atrium to left ventricle.

Rheumatic heart disease is by far the most common cause of MS. Obstruction of flow to the left ventricle results in raised atrial and pulmonary pressures and eventual right sided failure.

Symptomatic disease tends to present with dyspnoea and reduced exercise tolerance. Complications include atrial fibrillation and thromboembolic events. Interventional management, when indicated, is typically via percutaneous means.

Anatomy

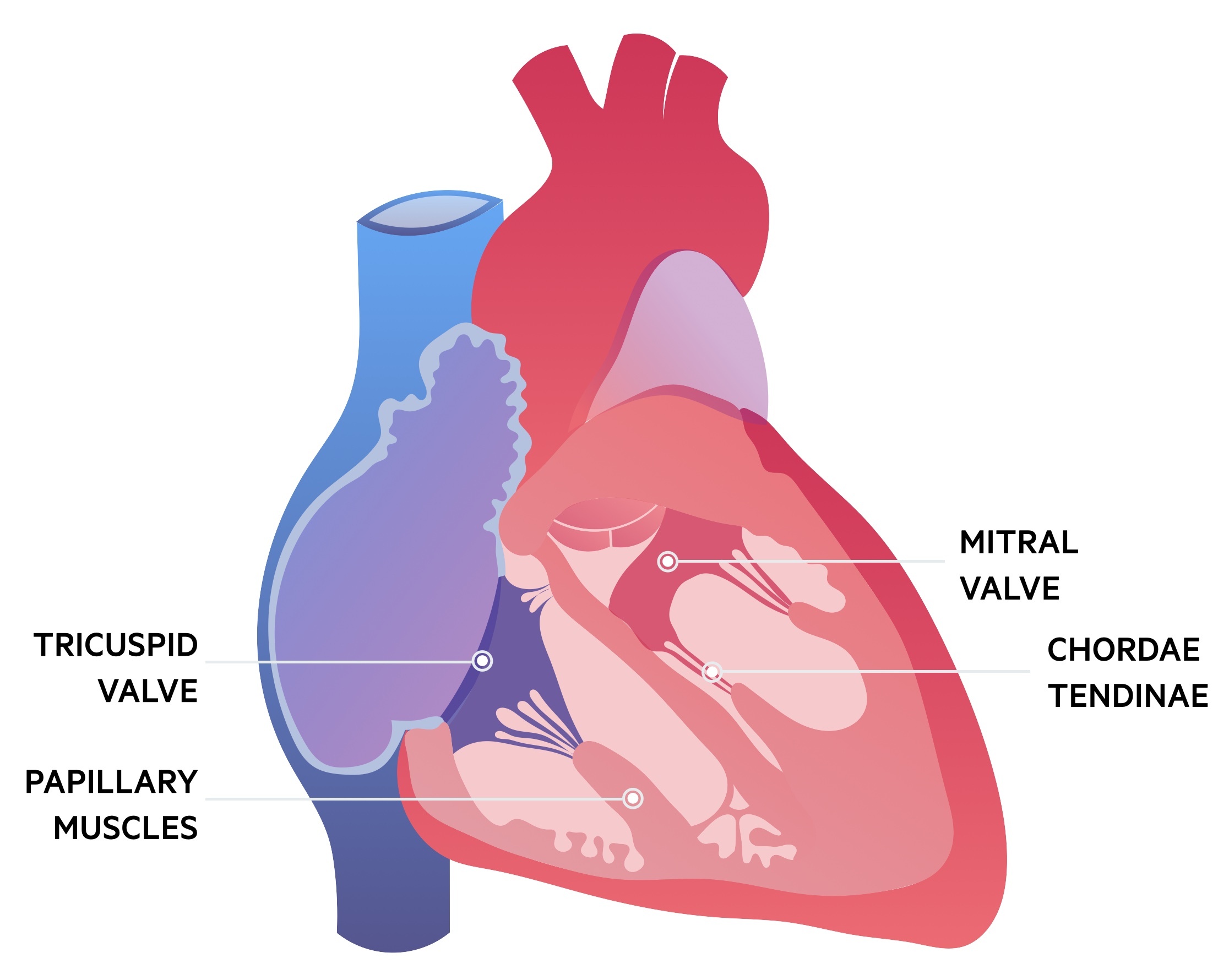

The mitral valve is termed (somewhat erroneously) a bicuspid valve and sits between the left atrium and ventricle.

The term atrioventricular valve complex refers to the entirety of the valve and its supporting apparatus. It consists of the orifice, valve leaflets, chordae tendineae, papillary muscles and the ventricle itself.

There are two valve leaflets, anterior and posterior. The posterior leaflet is divided by indentations into three scallops (P1, P2, P3). The corresponding areas on the anterior leaflet may also be divided to reflect the posterior scallops (A1, A2, A3). The normal cross-sectional area of the mitral valve orifice is 4-6 cm2.

Each leaflet is attached to chordae tendineae, which are string-like structures that connect leaflets to papillary muscles. Two papillary muscles support the mitral valve and arise from the ventricular wall. In normal physiology the mitral valve opens to allow left ventricular filling and closes during ventricular contraction.

Aetiology

Mitral stenosis most commonly results from rheumatic heart disease.

Rheumatic heart disease

Acute rheumatic fever is a non-suppurative complication of infection by group A Streptococcus (GAS) pharyngitis (‘strep throat’). Though increasingly uncommon in the western world due to wide-spread antibiotic use, it is still a significant cause of illness in the developing world.

It is thought to result from ‘molecular mimicry’ – this refers to cross-reactivity of antibodies produced to combat the GAS with normal tissues. This can result in symptoms like arthritis and carditis. The atrial and mitral valves are most commonly affected – with a small proportion of patients developing acute mitral or atrial insufficiency.

Most recover from the acute episode – however they can go on to develop progressive valvular disease that may not present symptomatically for many years. This chronic phase most commonly affects the mitral valve, with the aortic and tricuspid less frequently involved (the pulmonary valve is rarely affected). In the chronic phase stenosis, regurgitation or a mixed picture can be seen.

Other

The other causes of MS are all relatively rare. They include:

- Congenital MS

- Mitral annular calcification

- Radiation associated MS

- Carcinoid associated valve disease

- Fabry’s disease

NOTE: Lutembacher syndrome refers to a combination of an atrial septal defect and mitral stenosis (typically rheumatic heart disease related).

Pathophysiology

Mitral stenosis results in raised left atrial pressures and atrial remodelling.

Resistance to blood flow between the left atrium and ventricle results in an increase in the transmitral gradient. As MS progresses this leads to raised pressures in the left atrium – that may occur only during exercise or in more severe disease at rest. As the valve areas decreases (normal size is 4-6 cm2) progressive symptoms develop.

Left atrial enlargement occurs in the presence of chronically elevated atrial pressures predisposing patients to both atrial fibrillation and atrial thrombosis. Raised atrial pressures translate to raised pulmonary venous pressures and pulmonary hypertension which can eventually lead to right sided heart failure.

Clinical features

Mitral stenosis normally presents with exertional dyspnoea.

Dyspnoea is the most common presenting symptom. Typically it is first noticed on exertion though in older, less active patients this may go missed. It is indicative of raised atrial pressures and resultant pulmonary venous hypertension.

Less commonly patients may have haemoptysis as a result of vascular congestion and can result from the rupture of thin walled bronchial veins. Chest pain is occasionally seen, often a result of angina from underlying coronary artery disease and hypertrophic myocardium having increased oxygen demands.

A mid-diastolic murmur is characteristic – best heard with the bell of the stethoscope with the patient lying on their left side whilst breath is in held expiration.

Patients may occasionally present with Ortner syndrome – a horse voice that occurs secondary to left atrial enlargement causing a left recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy.

Symptoms

- Breathlessness

- Haemoptysis

- Chest pain

Signs

- Mid-diastolic murmur

- Atrial fibrillation

- Mitral facies (malar flush)

- Pulmonary hypertension:

- Right ventricular heave

- Prominent a-wave

- Right heart failure:

- Raised JVP

- Peripheral oedema

- Hepatomegaly

Thromboembolism

Patients with MS are at greatly increased risk of thromboembolic events. Clots that develop in a dilated left atrium, often in the presence of atrial fibrillation, may throw off emboli into the systemic circulation. As such patients may present with a stroke. Other organs are less commonly affected.

Diagnosis

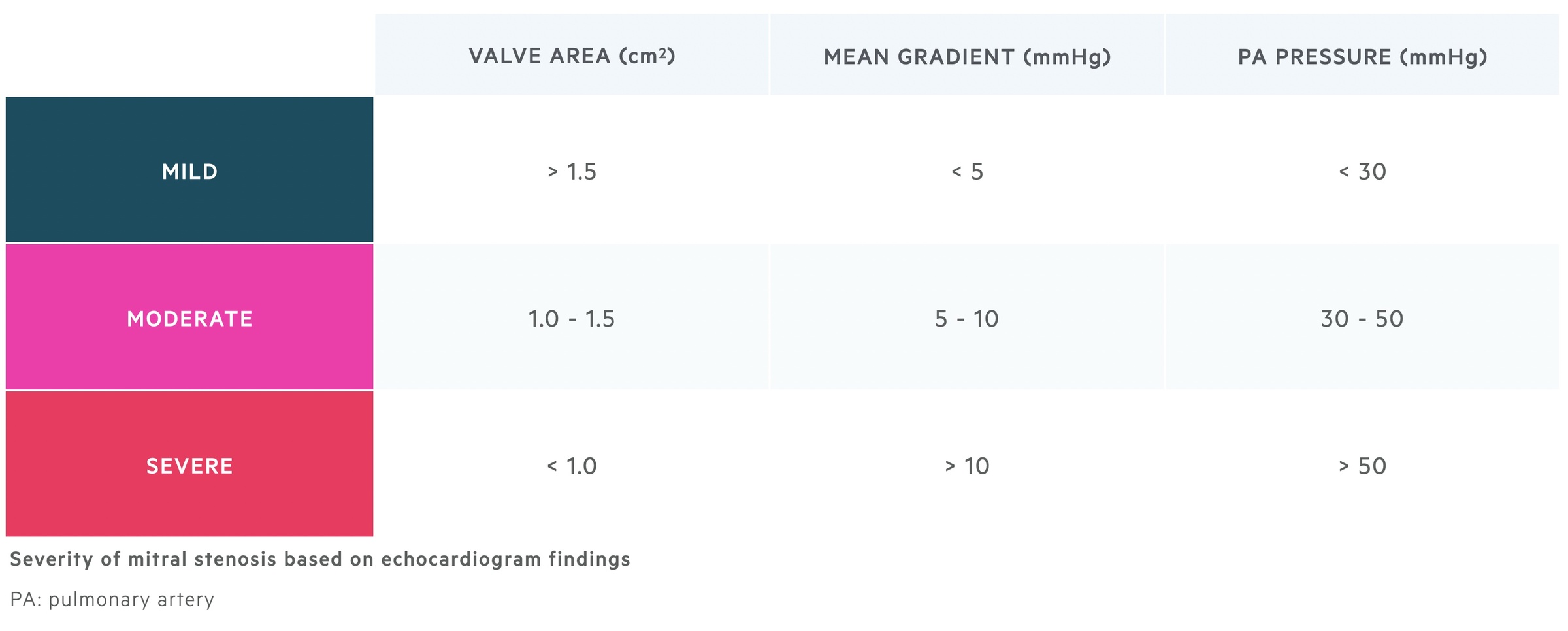

Echocardiogram is used to make the diagnosis of mitral stenosis and assess the severity of disease.

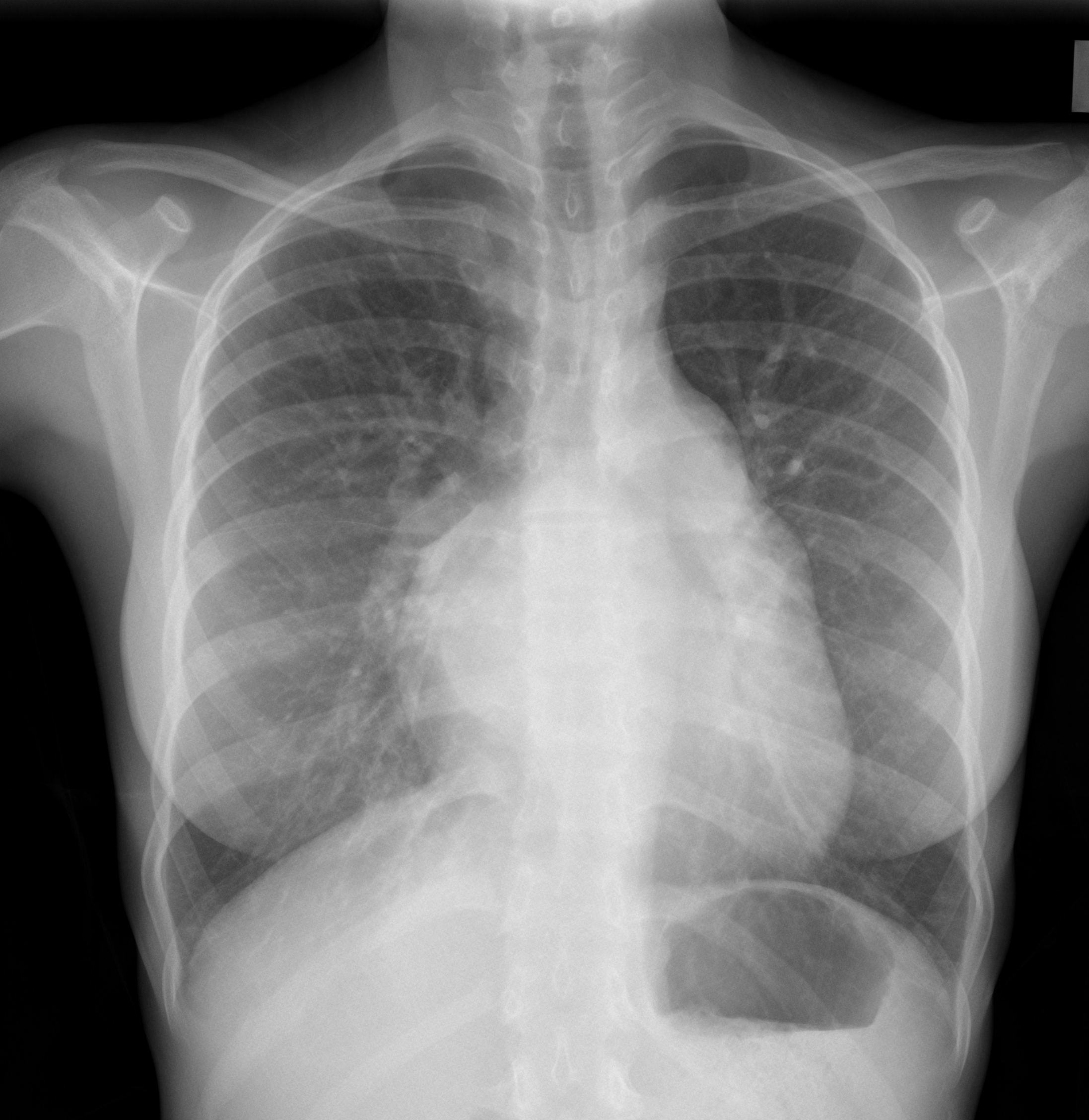

CXR

On the CXR left atrial enlargement can be seen. In those with pulmonary hypertension signs of this and right sided heart failure may also feature. The CXR shown below has a number of signs indicative of left atrial enlargement:

- Double right heart border

- Splayed trachea

- Prominence of the atrial appendage

CXR of patient with MS showing LA enlargement

Image courtesy of Dr Henry Knipe, Radiopaedia

ECG

Atrial fibrillation is common but the ECG may be normal or reflect remodelling. In those in sinus rhythm signs of left atrial enlargement may be seen with p-mitrale – a broad, notched p-wave with a negative component in V1. If right sided hypertrophy has developed right axis deviation and tall R-waves in V1 can be seen.

Echocardiogram

Transthoracic echocardiogram: This is normally sufficient for diagnosis and allows assessment of the mitral valve as well as any associated valvular pathology and changes to the heart. Both the valve area and transmitral gradient can be assessed.

Transoesophageal echocardiogram: Can be performed to look for left atrial thrombosis either after an embolic episode (e.g. stroke) or prior to percutaneous mitral commissurotomy.

Stress testing

Stress testing is somtimes used in those who are asymptomatic or have minor symptoms as well as those whose symptoms are discordant with echo findings. This may take the form of an exercise stress echo or dobutamine stress test.

Treatment

ESC/EACTS guidelines advise percutaneous mitral commissurotomy (PMC) as the treatment of choice in patients who meet the criteria for intervention and have favourable anatomy.

Interventional management

PMC refers to a minimally invasive approach that uses a balloon delivered by a catheter which enters at the right femoral vein. This balloon is then inflated in various stages to help alleviate the stenosis.

PMC tends to be reserved for patients with clinically significant MS and a valve area < 1.5cm2 in those who are symptomatic or at high-risk of embolism or haemodynamic decompensation. Contra-indications for PMC include:

- Valve area >1.5cm2

- Left atrial thrombus

- Absence of commissural fusion

- Severe or bi-commissural calcification

- More than mild mitral regurgitation

- Severe concomitant aortic stenosis requiring surgery

- Severe combined tricuspid regurgitation/stenosis requiring surgery

- Concomitant coronary artery disease requiring surgery

In those not suitable for PMC, open surgery may be considered and discussed with the patient.

Medical management

Patient with AF or paroxysmal AF can tend to follow the routine management of this condition. In stable patients pre-intervention, cardioversion is not indicated as the results are not sustained. Patients should receive appropriate anticoagulation.

ESC/EACTS advise that in patients with ‘moderate to severe mitral stenosis and persistent atrial fibrillation should be kept on vitamin K antagonist (VKA) treatment and not receive NOACs’.

In patient in sinus rhythm anticoagulation may still be advised if:

- Thrombus in the left atrium

- History of systemic embolism

It may also be considered in those with an enlarged LA or with dense spontaneous echocardiographic contrast.