Overview

Cardiac tamponade is a life-threatening condition that causes compression of the heart from pericardial content.

Cardiac tamponade is a life-threatening condition that is caused by compression of the heart from the accumulation of fluid, blood, clots, or gas within the pericardial space. Compression of the heart prevents adequate filling and contraction, which clinically results in ‘Beck’s triad’ that is a combination of hypotension, venous distension (i.e. raised JVP), and muffled heart sounds.

Cardiac tamponade is diagnosed through echocardiography and without urgent needle pericardiocentesis it can lead to cardiac arrest.

The pericardium

The serous pericardium is a double layered membrane that surrounds the heart.

Anatomy

The pericardium is composed of a tough, outer fibrous layer and an inner, serous layer. The combined thickness of these layers is 1-2mm. The fibrous pericardium is a tough sac, which completely surrounds the heart but remains unattached.

The serous pericardium is composed of two membranes that line the heart. These are the parietal and visceral pericardium. Between these two membranes is a small volume of fluid.

- Parietal pericardium: internal surface of the fibrous pericardium

- Visceral pericardium: inner membrane, known as the ‘epicardium’, which covers the heart and great vessels

- Pericardial space: contains a small amount of serous fluid (20-50 mls)

Physiology

The pericardium has three main physiological functions:

- Mechanical: limits cardiac dilation, maintains ventricular compliance (i.e. relationship between volume and pressure), and aids atrial filling.

- Barrier: reduces external friction and acts as a barrier.

- Anatomical: fixes the heart through its ligamentous function.

Pericardial effusions

A pericardial effusion essentially refers to excess fluid (or other substances) within the pericardial space.

The normal pericardial sac contains 20-50 mL of pericardial fluid. This acts to prevent friction between the pericardial layers. Excess fluid may accumulate in the pericardial sac due to inflammation and increased production, reduced reabsorption from increased venous pressure, or haemorrhage into the sac.

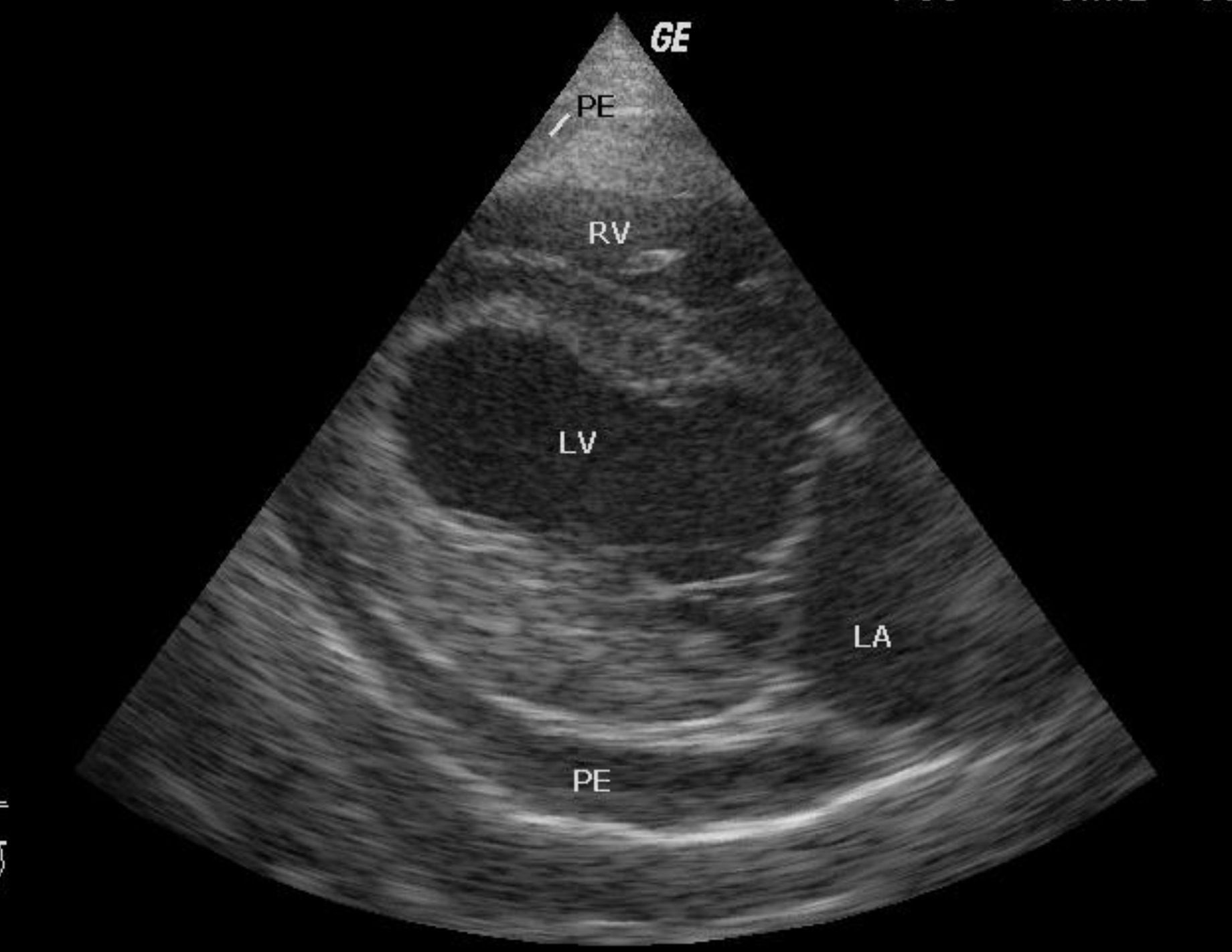

Pericardial effusion (PE) seen on ECHO

Image courtesy of Kalumet. Wikimedia commons

Classification

Pericardial effusions can be classified by four major factors:

- Onset: acute, subacute, chronic (>3 months)

- Size: mild (< 10 mm), moderate (10-20 mm), large (> 20 mm)

- Distribution: circumferential or loculated

- Composition: transudate or exudate

Haemodynamic impact

An effusion can lead to increased pericardial pressure that compresses all chambers of the heart. The speed of pericardial fluid accumulation will commonly determine the clinical presentation.

If accumulation occurs acutely, it can lead to the rapid development of haemodynamic compromise (i.e. hypotension) due to inadequate filling even with small amounts of fluid. If the accumulation occurs slowly, it may take several weeks before clinical symptoms and features of haemodynamic compromise occur.

Aetiology

Any cause of pericardial effusion or haemorrhage into the pericardium can lead to cardiac tamponade.

Cardiac tamponade essentially refers to the haemodynamic compromise that occurs secondary to excess fluid (or other substances) within the pericardial space. Any pathology leading to effusion or blood within the pericardial space can cause tamponade.

Common causes

- Pericarditis

- Tuberculosis

- Iatrogenic (e.g. post invasive cardiac procedure)

- Trauma

- Malignancy

Uncommon causes

- Connective tissue disease

- Radiation-induced

- Uraemia

- Post-myocardial infarction

- Aortic dissection

- Bacterial infection

Pathophysiology

The main physiological problem in cardiac tamponade is compression of the heart chambers due to increased pericardial volume.

The pericardial sac has a degree of elasticity but as an effusion increases in size, there is increased pressure that starts to compress all four chambers of the heart. As pressure increases, the chambers become smaller in size and there is decreased diastolic compliance. Diastolic compliance essentially refers to how ‘stiff’ the heart is and plays a big factor in ventricular filling and end-diastolic pressure. Cardiac tamponade reduces venous return that restricts ventricular filling and this leads to a reduction in stroke volume and cardiac output. The end result is a decrease in blood pressure and haemodynamic compromise.

Due to the normal physiological alteration in venous return in relation to respiration (i.e. inspiration/expiration), a classic sign develops in cardiac tamponade known as pulsus paradoxus. This refers to a decrease in systolic arterial BP > 10 mmHg during inspiration.

During inspiration, venous return normally increases to the right side of the heart and pulmonary venous return decreases to the left side of the heart. When the heart is compressed in tamponade, only the interventricular septum distends partially on inspiration. This septum bulges into the left ventricle, further impeding ventricular filling and results in a greater fall in blood pressure.

Clinical features

Patients with acute cardiac tamponade present with hypotension due to cardiogenic shock.

The clinical presentation of cardiac tamponade depends on the speed of development of the effusion. In acute cardiac tamponade, patients may present with profound hypotension, cardiogenic shock, and even cardiac arrest. In subacute cardiac tamponade, there may be slow development of dyspnoea, chest pain and peripheral oedema over weeks.

Symptoms

- Chest pain

- Dyspnoea

- Collapse

- Fatigue

- Peripheral oedema (subacute)

Signs

The classic examination findings in cardiac tamponade are ‘Beck’s Triad’. This describes a combination of hypotension, elevated venous pressure (i.e. distended JVP) and muffled heart sounds.

- Tachycardia

- Hypotension

- Distended JVP

- Muffled heart sounds

- Pulsus paradoxus: decrease in systolic blood pressure (>10 mmHg) on inspiration

- Pericardial rub: may occur with pericarditis

- Other features of shock: cool extremities, peripheral cyanosis, reduced urine output

Diagnosis & investigations

Cardiac tamponade is diagnosed with urgent echocardiography.

Echocardiography (i.e. ECHO) is the principal investigation for cardiac tamponade that is able to demonstrate the pericardial effusion and its haemodynamic impact on the heart. Any patient with suspected cardiac tamponade requires an urgent ECHO.

ECHO features

Some examples of echocardiographic features of cardiac tamponade include:

- Chamber collapse: early diastolic collapse of the right ventricle and late diastolic collapse of the right atrium

- Respiratory variation in volume and flow: alteration in mitral valve flow, ventricular septal motion, and ventricular volumes

- IVC plethora: dilatation of the IVC and < 50% reduction in diameter during inspiration are features of elevated venous pressure

Other investigations

An ECG is an important baseline investigation for suspected cardiac tamponade. It may show features of acute pericarditis or simply sinus tachycardia with low voltage complexes (i.e. small). Another typical finding may be electrical alternans, which describes beat-to-beat variation in the size of QRS complexes.

A chest x-ray may show an enlarged cardiac silhouette. However, findings may be normal, particularly in acute cardiac tamponade when only a small amount of fluid is needed to precipitate significant haemodynamic compromise.

A pericardial effusion may be detected on CT or MRI. However, these should not be requested for acute cardiac tamponade that can be life-threatening.

CT thorax showing a pericardial effusion (black arrow)

Image courtesy of James Heilman, MD. Wikimedia commons.

Management

The principal management of cardiac tamponade is an urgent needle pericardiocentesis.

Management of cardiac tamponade involves urgent drainage of the pericardial fluid, usually via needle pericardiocentesis. This involves the insertion of a needle into the pericardial space and removing the surrounding fluid with or without insertion of a pericardial drain.

Depending on the urgency of the situation, this may be performed by anatomical landmarks, with echocardiography guidance, or using fluoroscopy in a cardiac suite. Cardiac surgery may be an alternative option to drain a pericardial effusion causing tamponade in some situations. Major complications of pericardiocentesis include bleeding and left ventricular failure.