Introduction

Aortic regurgitation results from an incompetent aortic valve causing a regurgitant flow of blood in diastole.

Aortic regurgitation tends to present between the fourth and sixth decades of life. It affects males three times more commonly than women. Severe disease is seen in < 1% of the population. The most common causes are degenerative disease and congenital bicuspid valve.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of aortic regurgitation increases with advancing age.

In a cohort of the Framingham Heart Study in 1999, in people aged 44-64, a research group found 13% of men and 8.5% of women were affected by trace or greater (i.e. mild, moderate, severe) aortic regurgitation. More significant regurgitation was seen more commonly in older patients.

In a study of African-Americans aged 50 and older, published in 2007 by Fox et al, 6.1% had trace, 9% mild and 0.5% moderate or greater aortic regurgitation. Again more significant regurgitation was seen in older age groups.

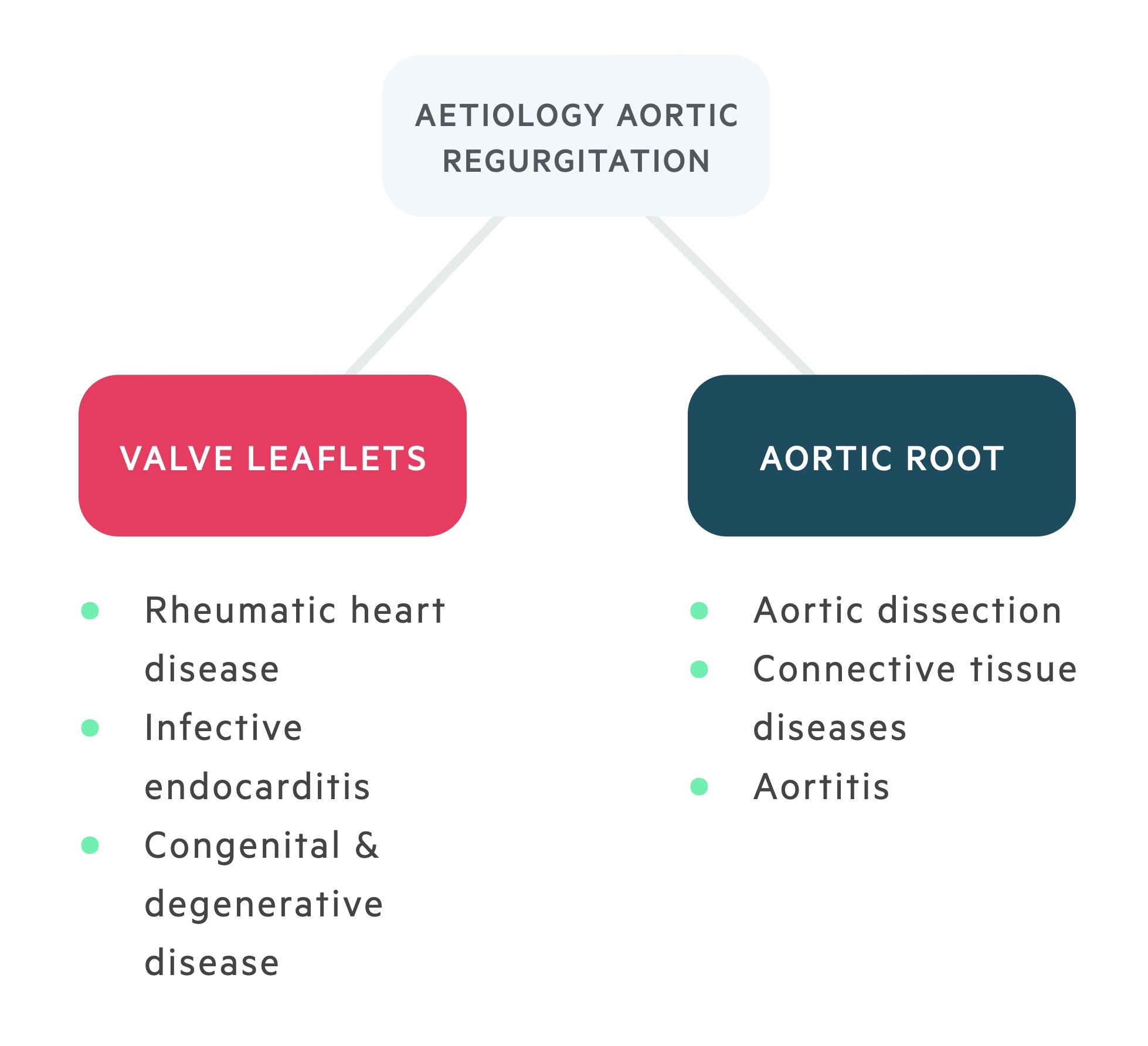

Aetiology

Causes of AR can be split into either primary disease of the aortic valve leaflets; or dilation of the aortic root.

Valve leaflets

Rheumatic heart disease

An autoimmune condition which follows streptococcal (Group A) infection. Inflammation is a result of molecular mimicry. In effect, the immune system produces antibodies that confuse foreign- and self-antigens. Rheumatic heart disease results from cardiac inflammation with acute and chronic results.

Commonest cause in the developing world. Although an increasingly uncommon cause of valvular disease. Chronic disease leads to fibrosis and typically a stenotic valve though regurgitant valves may also develop.

Congenital & degenerative

Constitute the commonest causes of aortic regurgitation in the developed world.

- Congenital (e.g. bicuspid, quadcuspid valve).

- Degenerative (e.g. calcification).

Endocarditis

Inflammation of the endocardium, typically as a result of infection. Results in acute disease. Vegetations may cause flailing of the valve leaflets.

Infective causes include Strep. viridans, Staph. aureus, Enterococci.

Aortic root

Connective tissue disorders

Aortic regurgitation may feature in a number of connective tissue disorders. Aortic root diameter should be monitored in these individuals.

- Marfan’s syndrome – caused by a defect in the FBN1 gene.

- Ehlers-Danlos syndrome – caused by collagen defects.

Aortitis

Aortitis refers to inflammation of the aortic root. May be associated with chronic inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and ankylosing spondylitis (AS). Also, may occur in Takayasu arteritis, or may complicate Giant cell arteritis.

Aortic dissection

Aortic regurgitation may complicate in Stanford A dissections, secondary to impaired leaflet coaptation or prolapse. Causes acute disease regurgitation and is a medical emergency.

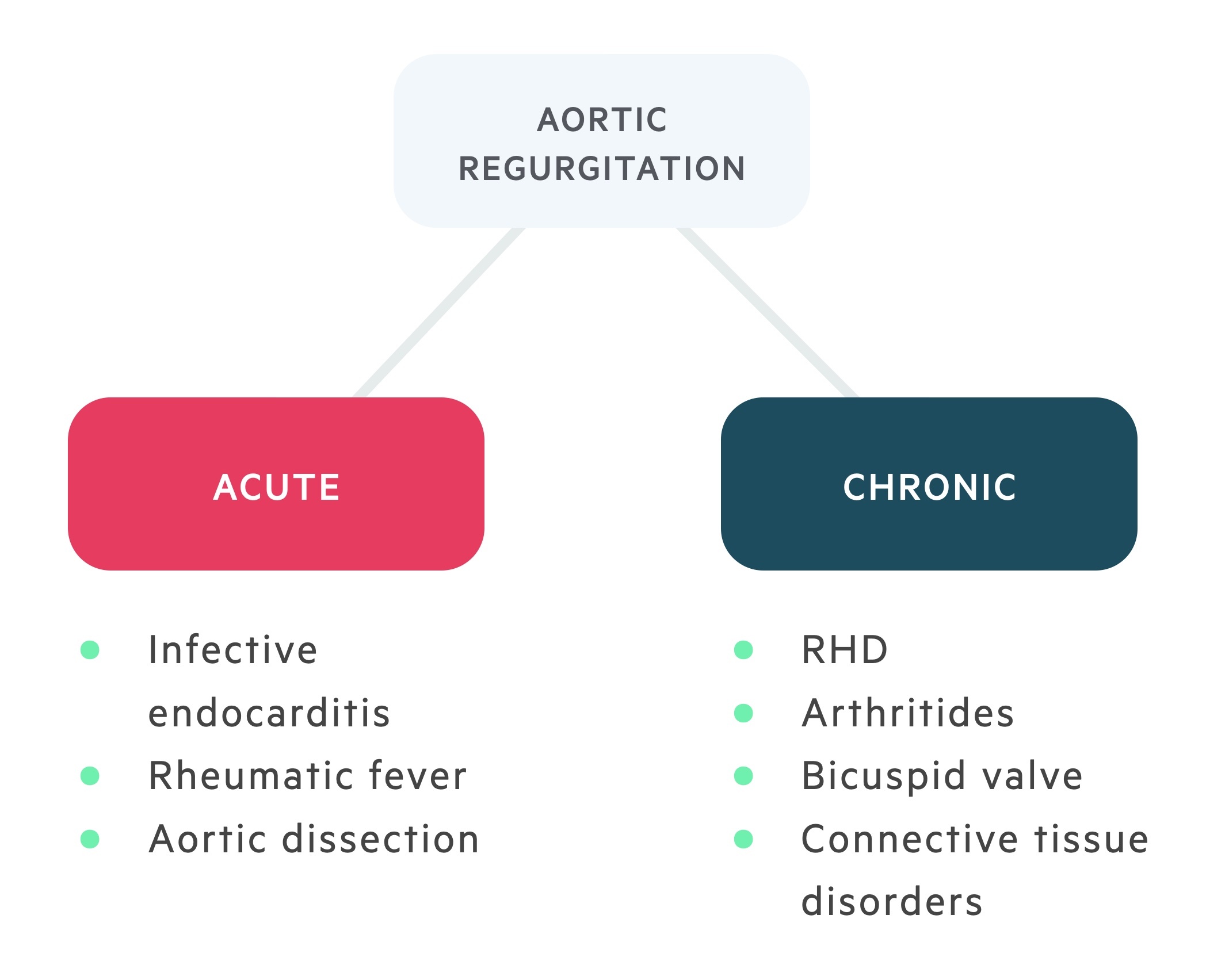

Pathophysiology

Aortic regurgitation may develop acutely or chronically over a period of many years.

Acute

Acute aortic regurgitation is a medical emergency – an acute rise in left atrial pressure results in pulmonary oedema & cardiogenic shock. Valvular incompetence occurs rapidly and the compensatory changes seen in chronic disease do not have time to develop. Regurgitation of blood during diastole causes an increase in the left ventricular end-diastolic volume (and pressure).

The effects of this are two-fold:

- Reduced coronary flow – the coronaries fill predominantly during diastole, regurgitant flow at this time reduces filling. Results in angina or in severe cases myocardial ischaemia.

- Increased end-diastolic pressure – causes increased pulmonary pressures with resulting pulmonary oedema and dyspnoea. In severe cases, cardiogenic shock may occur.

Chronic

In chronic aortic regurgitation, patients may remain asymptomatic for many decades. Valvular incompetence develops slowly. Regurgitation of blood during diastole causes an increase in the left ventricular end-diastolic volume (essentially the preload). This leads to systolic and diastolic dysfunction, left ventricular dilatation develops with eccentric hypertrophy.

The dilation allows for an increased stroke volume compensating for regurgitant flow supported by the ventricular hypertrophy. These changes maintain ejection fraction, with a greater preload leading to greater contractility (see notes ‘Heart failure’ subsection ‘Frank-Starling law’).

Eventually further increases in preload cannot be met by greater contractility and heart failure develops.

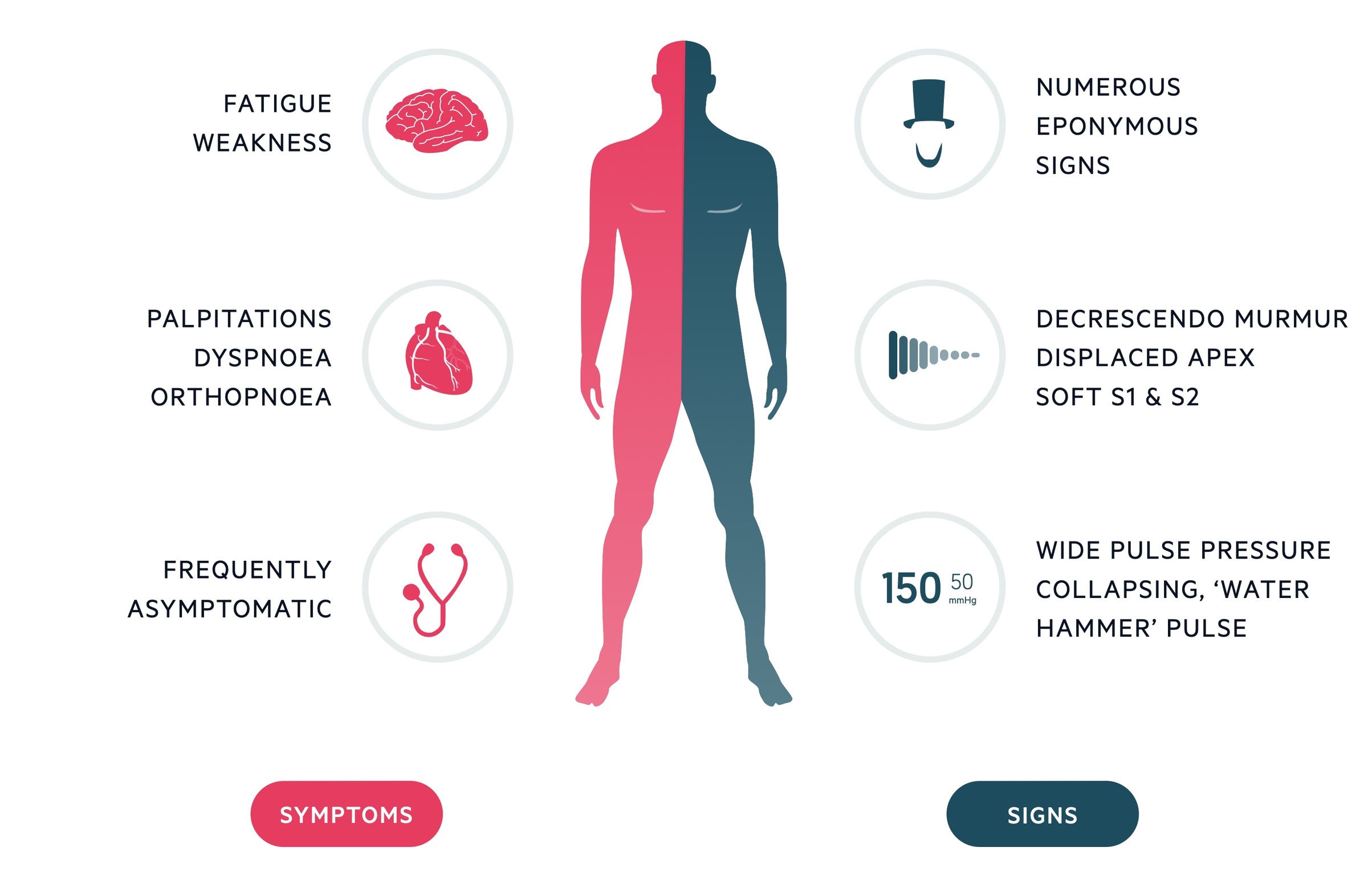

Clinical features

Patients may present acutely with features of heart failure in acute AR or have a prolonged period of little to no symptoms followed by gradual onset of symptoms in chronic disease.

Acute AR

- Sudden dyspnoea

- Chest pain (consider angina, MI or aortic dissection)

- Bi-basal crackles

- Raised JVP

Chronic AR

- Palpitations

- Angina

- Dyspnoea

- Water hammer pulse

- Wide pulse pressure

- Chest signs:

- Displaced apex

- Ejection diastolic murmur

- Soft S1 and S2

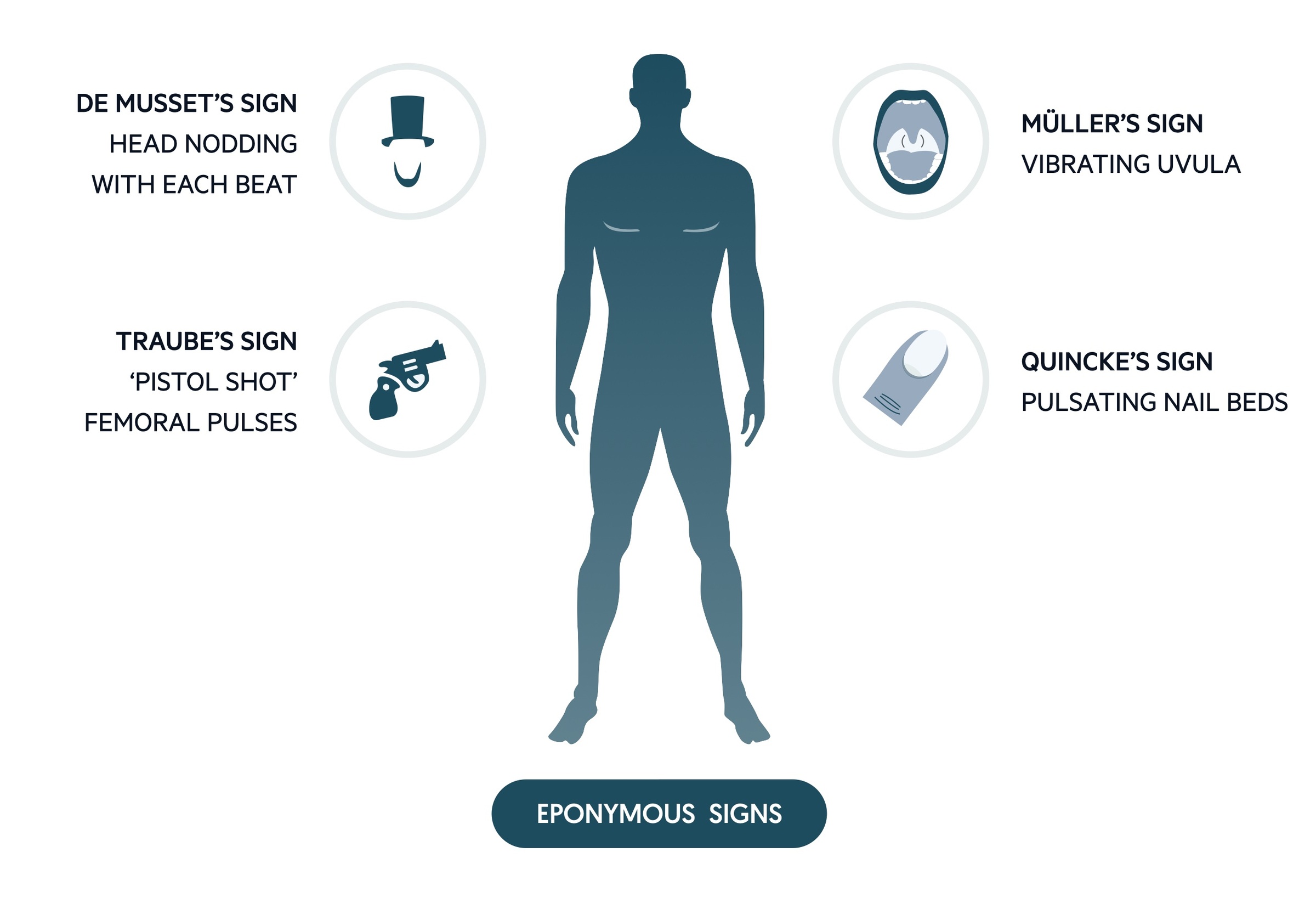

Eponymous signs

Often asked about in examinations, the relevance of these signs in clinical practice today is questionable.

- de Musset’s – head nodding with the heart beat.

- Quincke’s – pulsation of nail beds.

- Traube’s – pistol shot femorals.

- Duroziez’s – to and fro murmur heard when stethoscope compresses femoral vessels.

- Müller’s – pulsation of uvula.

Investigations & diagnosis

Echocardiogram is the key diagnostic exam in patients with suspected aortic regurgitation.

Bedside

- Observations

- Blood pressure

- ECG: left ventricular hypertrophy (deep S-waves in V1 and V2, tall R-waves in V5 and V6) in chronic AR

Bloods

- FBC

- U&Es

- Cholesterol

- Clotting

Imaging

Echocardiogram: transthoracic echocardiography/transoesophageal echocardiography is the key diagnostic investigation. It allows visualisation of the origin of regurgitant jet and its width, detection of aortic valve pathology and compensatory changes (e.g. left ventricular hypertrophy in chronic AR).

CXR: the most common sign in chronic AR is cardiomegaly. Signs of heart failure are seen in acute AR and advanced chronic AR. It may show a dilated ascending aorta in those with aortic root pathology though the sensitivity is poor.

CT/MRI: MRI may be used to estimate the regurgitant fraction if echo results are equivocal. In patients with aortic dilatation, gated multi-slice CT is the imaging of choice to characterise aortic dilatation and the maximum diameter.

Angiography: in patients with chronic AR undergoing surgery, pre-operative angiography is indicated. Typically this is in the form of coronary angiography (invasive procedure) to assess for concomitant coronary artery disease that may require bypass.

Management

Surgical aortic valve replacement or repair is indicated in severe disease, symptomatic disease or in the presence of significant enlargement of ascending aorta.

Acute AR

Acute AR is a surgical emergency. Aortic valve replacement or repair should be performed as soon as possible. It primarily occurs secondary to infective endocarditis or aortic dissection, both of which carry very high morbidity and mortality:

- Aortic dissection (Stanford type A): management depends on the patients pre-morbid state and severity of presentation. If not already there, patients are transferred to the local on-call dissection centre. Emergency open surgery is typically required, management depends on the exact pattern of findings but may consist of root replacement and valve repair or replacement.

- Infective endocarditis: management depends upon pattern of valvular involvement (multiple valves may be affected) and complications (e.g. annular/aortic abscess, septic emboli). Coronary angiogram may be performed in selected stable patients prior to operative management. AR is generally an indication for early surgery.

Chronic AR

According to the 2017 ESC guidelines, surgical management is indicated (depending on individual operative risk) in chronic AR in patients with:

- Significant enlargement of the ascending aorta or

- Symptomatic severe AR or

- Severe AR with LVEF ≤ 50% or LVEDD > 70mm or LVESD > 50mm (may be adjusted for body size)

- Marfan’s with aortic root disease with a maximal ascending aorta diameter ≥ 50mm

The decision of mechanical vs bioprosthetic valve should take into account patient-specific factors and wishes:

- Mechanical valve – require long-term anticoagulation, long lifespan reducing the need for a second operation. Suited to younger patients.

- Bioprosthetic valve – no need for long-term anticoagulation, limited life span (around 10 years) and a repeat operation is more likely. Suited to older patients.

Increasingly at expert centres aortic valve repairs are being conducted in select patients and use become more common going forward. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has been used in patients in whom surgery is contra-indicated but its role in the management of AR has not been formally established.

In those with ascending aorta dilatation management depends on the anatomical pattern, patients may need root replacement with reimplantation of the coronary vessels either with preservation of the native valve or with replacement or a supracommissural tube graft replacement.