NOTES

Overview

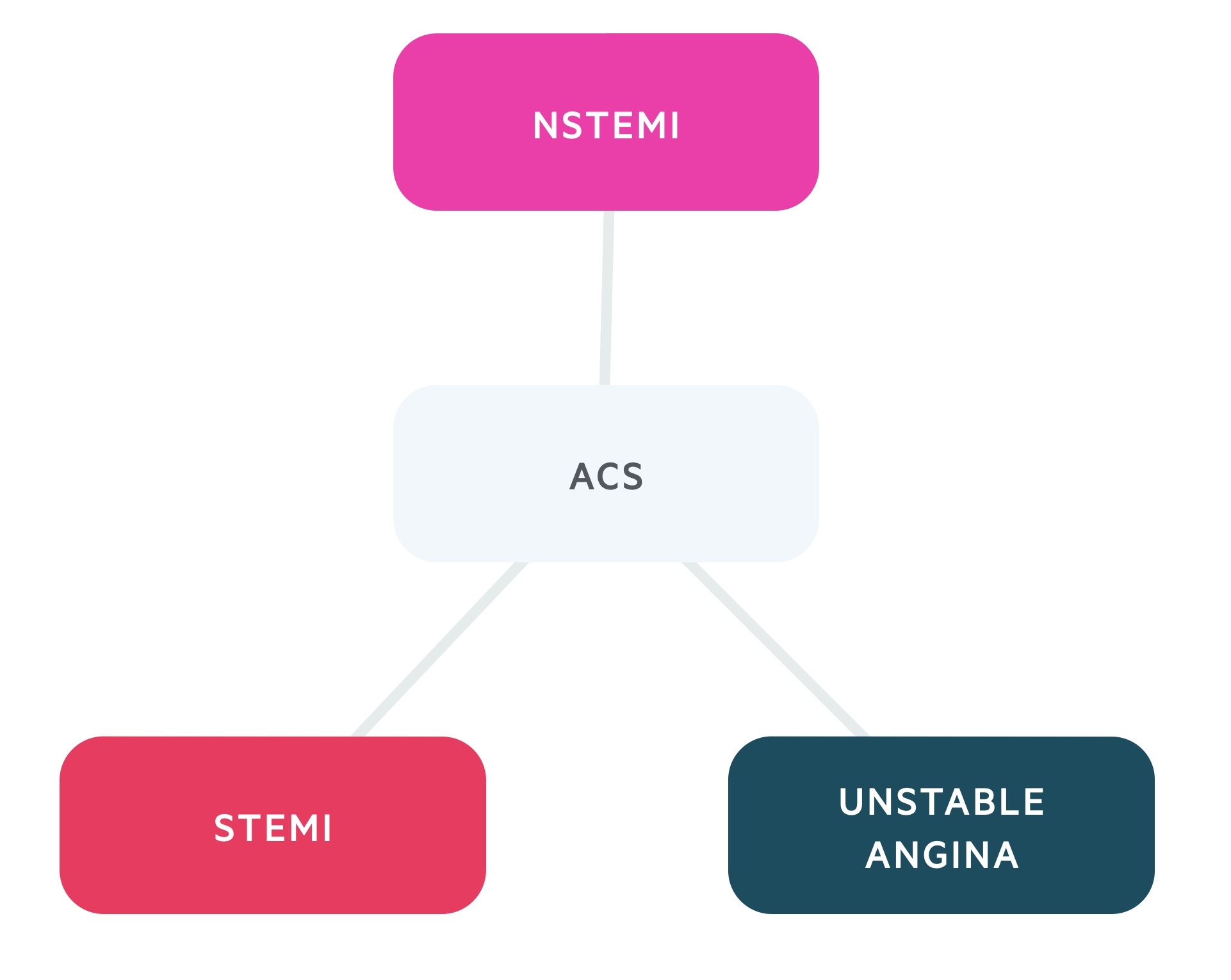

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) refers to three states of myocardial ischaemia: unstable angina (UA), non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).

ACS is a medical emergency requiring urgent admission. Around 100,000 people are admitted with ACS in the UK each year. Atherosclerosis represents the most significant aetiological factor.

Classification

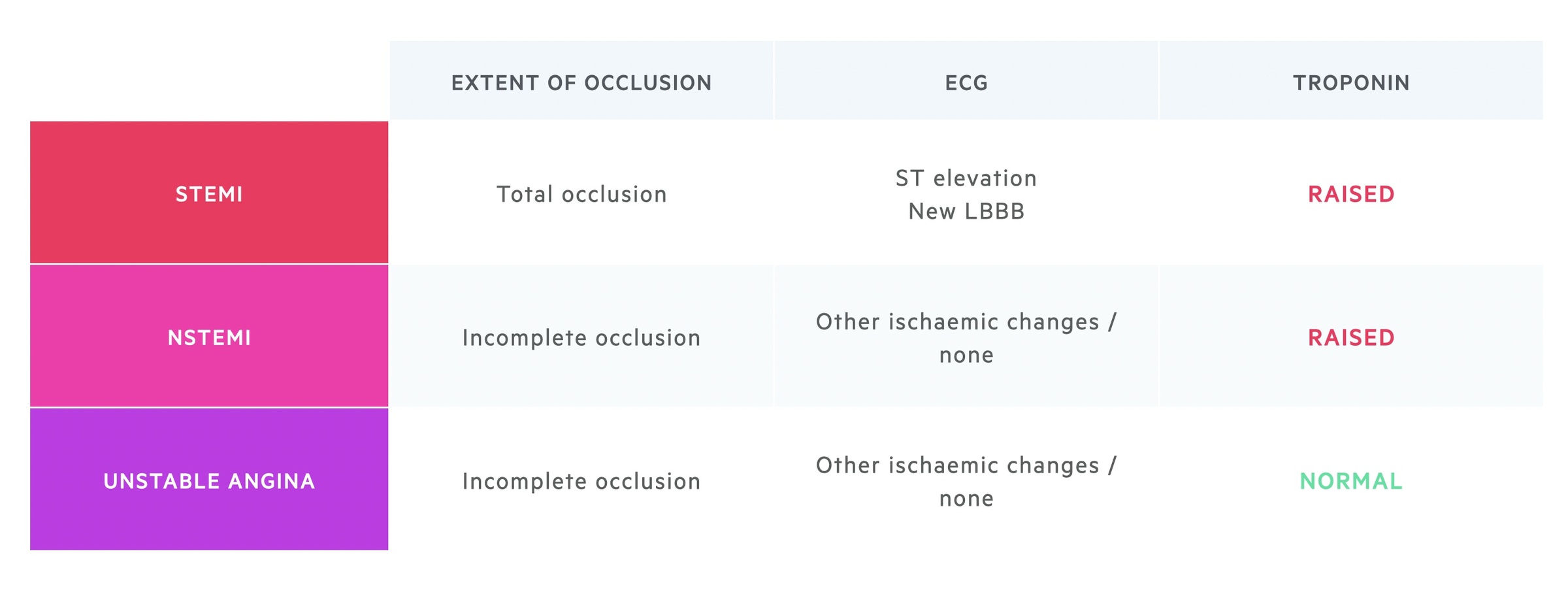

ACS is classified into one of three conditions according to clinical features, ECG findings and cardiac enzymes:

- STEMI: ST-segment elevation or new-onset left bundle branch block and raised troponins.

- NSTEMI: Non-specific signs of ischaemia or normal ECG, raised troponins.

- UA: Characteristic clinical features, non-specific signs of ischaemia or normal ECG, normal troponins.

Definition

A myocardial infarction (MI), which is more colloquially known as a ‘heart attack’, refers to death of cardiac tissue (i.e. myocardial necrosis).

MI is defined as ‘evidence of myocardial necrosis in a clinical setting consistent with acute myocardial ischaemia’. For the diagnosis, it requires the detection of a cardiac biomarker (e.g. troponin) to show a rise and/or fall with at least one value above the upper limit for normal (ULN).

In addition, there should be at least one of the following:

- Symptoms of myocardial ischaemia (e.g. chest pain)

- New or presumed new ECG changes: ST-T wave changes or new LBBB

- Development of pathological Q waves

- Imaging evidence of infarction: loss of viable myocardium or new motion abnormality

- Angiography or autopsy evidence of thrombus

Aetiology

ACS is typically triggered by rupture of an atheromatous plaque in the coronary arterial wall.

Atherosclerosis is the predominant cause of ACS. Atherosclerosis leads to narrowing of the coronary vessels, which supply the heart. Narrowing secondary to atherosclerosis is known is coronary artery disease (CAD) or ischaemic heart disease (IHD).

CAD/IHD can lead to angina, which refers to typical chest pain from myocardial ischaemia when there is an increase in the oxygen supply/demand (e.g. on exertion). This quickly improves on rest. If an atheromatous plaque ruptures, it leads to thrombus formation and acute occlusion that causes ACS (i.e. leads to myocardial necrosis, ECG changes and typical symptoms). See pathophysiology.

Risk factors

There are a number of risk factors that increase the chance of developing atherosclerosis, they may be divided into modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors.

Modifiable risk factors:

- High cholesterol

- Hypertension

- Smoking

- Diabetes

- Obesity

Non-modifiable risk factors:

- Age

- Family history

- Male sex

- Premature menopause

Other causes

Causes other than atheromatous plaque rupture can lead to myocardial infarction and ACS. Some also result in vessel occlusion (e.g. emboli, dissection), whereas others are due to oxygen supply/demand mismatch (e.g. anaemia).

In oxygen supply/demand mismatch, there is not total occlusion. Instead, there is not enough blood being delivered through the coronary arteries to meet the demand of the cardiomyocytes. This leads to necrosis and troponin rise.

Other causes of emboli:

- Valvular disease

Other causes of coronary occlusion:

- Vasculitis (e.g. Kawasaki disease)

- Coronary vasospasm (e.g. spontaneous, cocaine)

- Coronary dissection

Changes in oxygen demand and / or delivery:

- Anaemia

- Hyperthyroidism

- Severe sepsis

Types of myocardial infarction

There is a spectrum of acute and chronic myocardial damage that may occur with or without ischaemia.

There are two key terms to recognise:

- Myocardial infarction: myocardial necrosis, seen as a rise in troponin, with evidence of acute myocardial ischaemia

- Myocardial injury: myocardial necrosis, seen as a rise in troponin, without evidence of acute myocardial ischaemia

Myocardial infarction can be further divided into different types based on the aetiological mechanism:

- Type 1: due to a primary coronary artery event such as plaque rupture and/or dissection

- Type 2: due to an oxygen supply/demand mismatch

- Type 3: sudden unexpected cardiac death presumed secondary to myocardial ischaemia

- Type 4: associated with percutaneous coronary intervention or stent complications

- Type 5: associated with cardiac surgery

In clinical practice, the main subtypes that are clinically relevant are type 1 and type 2. It may be difficult to distinguish between these two types. If there is any doubt, patients needs to be managed as type 1 with antiplatelets and other medications to treat a plaque rupture myocardial infarction.

Examples of myocardial injury include:

- Myocarditis

- Damage following cardioversion/ablation

- Cytokine-mediated injury

NOTE: if can be difficult to distinguish patients with myocardial injury from type 2 myocardial infarction. In fact, the aetiology may be multifactorial in some cases, especially if the person has underlying CAD.

Pathophysiology

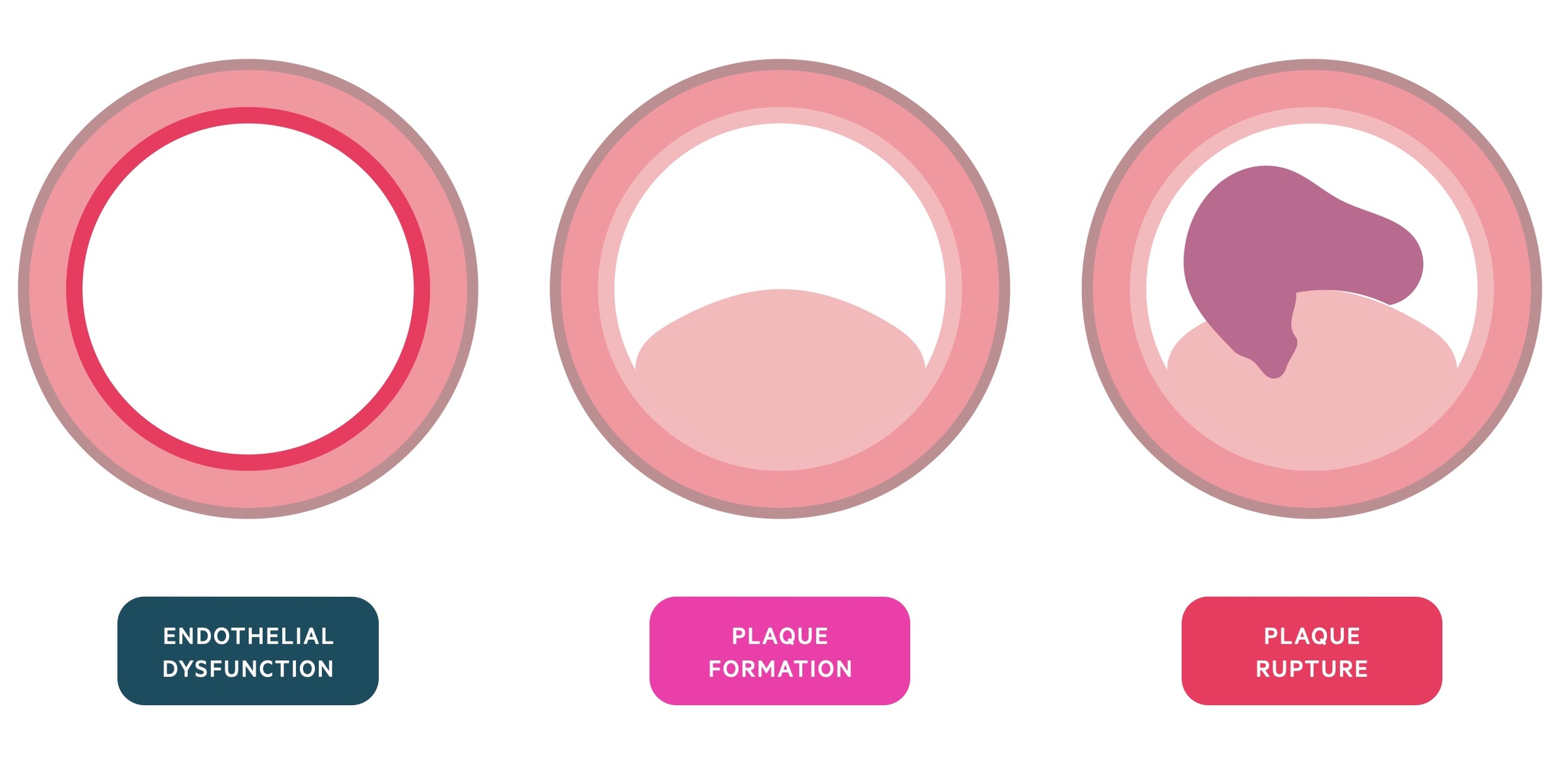

Atherosclerosis is an inflammatory process which predisposes individuals to ACS. It is a complex cellular process involving lipids, macrophages and smooth muscle.

Step 1 – endothelial dysfunction

The first step is endothelial injury. This causes a local inflammatory response. If the injury recurs or healing is incomplete, inflammation may continue leading to the accumulation of low-density lipoproteins (LDL). These become oxidised by local waste products creating reactive oxygen species (ROS).

Step 2 – plaque formation

In response to these irritants, endothelial cells attract monocytes (macrophages). These engulf (phagocytose) the LDLs swelling to become foam cells and ‘fatty streaks’.

Step 3 – plaque rupture

Continued inflammation triggers smooth muscle cell migration. This forms a fibrous cap, which together with the fatty streaks, develops into an atheroma.

The top of the atheroma forms a hard plaque. This may rupture through its endothelial lining exposing a collagen-rich cap. Platelets aggregate on this exposed collagen forming a thrombus that may occlude or severely narrow the vessel. Alternatively, the thrombus may break lose, embolising to infarct a distant vessel.

Clinical features

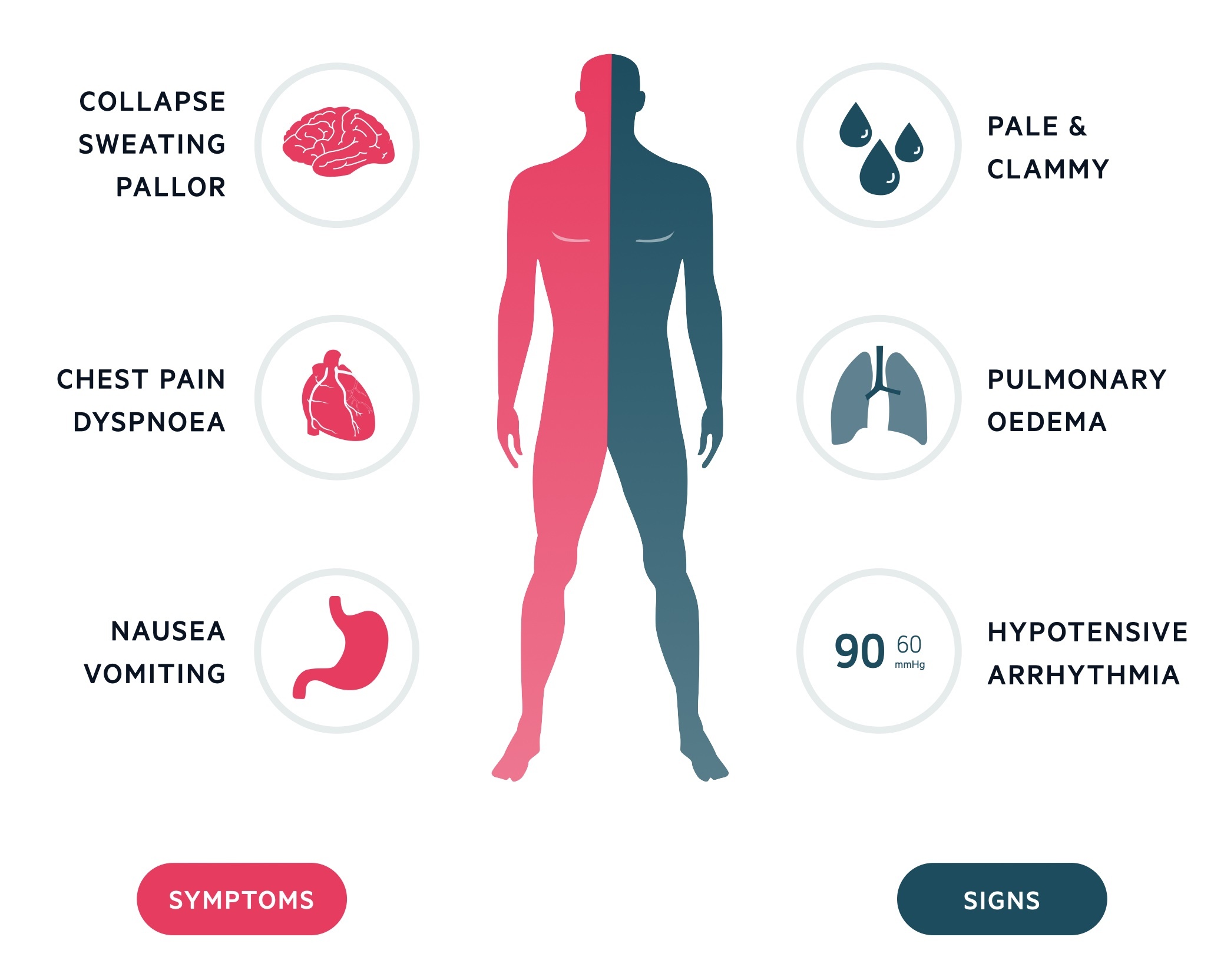

The signs and symptoms of ACS are related to myocardial ischaemia and an elevated autonomic (sympathetic) response.

Symptoms

- Chest pain > 15 minutes: central crushing or pressing pain +/- radiation to neck or arm

- Shortness of breath

- Sweating

- Nausea and vomiting

- Palpitations

Signs

- Pale

- Clammy

- Tachycardia

- Cardiac failure (e.g. pulmonary oedema, hypotension)

Other presentations

Remember, ACS may present with atypical clinical features, particularly in elderly patients or those with significant co-morbidities (e.g. diabetes mellitus). It can even occur in the absence of overt pain.

ACS may also present with severe complications such as cardiac arrest, life-threatening arrhythmia or acute heart failure.

Initial assessment

ACS necessitates a quick and accurate diagnostic process combining history, examination, ECG results and laboratory findings (e.g. cardiac enzymes).

The three key parts of the work-up for a patient presenting with suspected ACS includes:

- Brief clinical assessment: ABCDE (if acutely unwell) followed by brief history & examination.

- ECG: urgent ECG to look for ST elevation or left bundle branch block (LBBB). If absent, look for other features of ischaemia (e.g. ST depression, T wave inversion)

- Cardiac enzymes: troponin is the only recognises biomarker for the diagnosis of myocardial necrosis.

Diagnostic summary

The changes observed on ECG and rise in troponin can be used to differentiate the three causes of acute coronary syndrome:

ECG

An urgent ECG is required in all patients with suspected ACS.

Initially, the ECG is key to determine whether there is ST elevation or new left bundle branch block (LBBB), which warrants immediate transfer to a cardiac centre for consideration of primary percutaneous coronary intervention. In NSTEMI/UA there may be features suggestive of ischaemia (e.g. ST depression or T wave inversion) or the ECG may be normal.

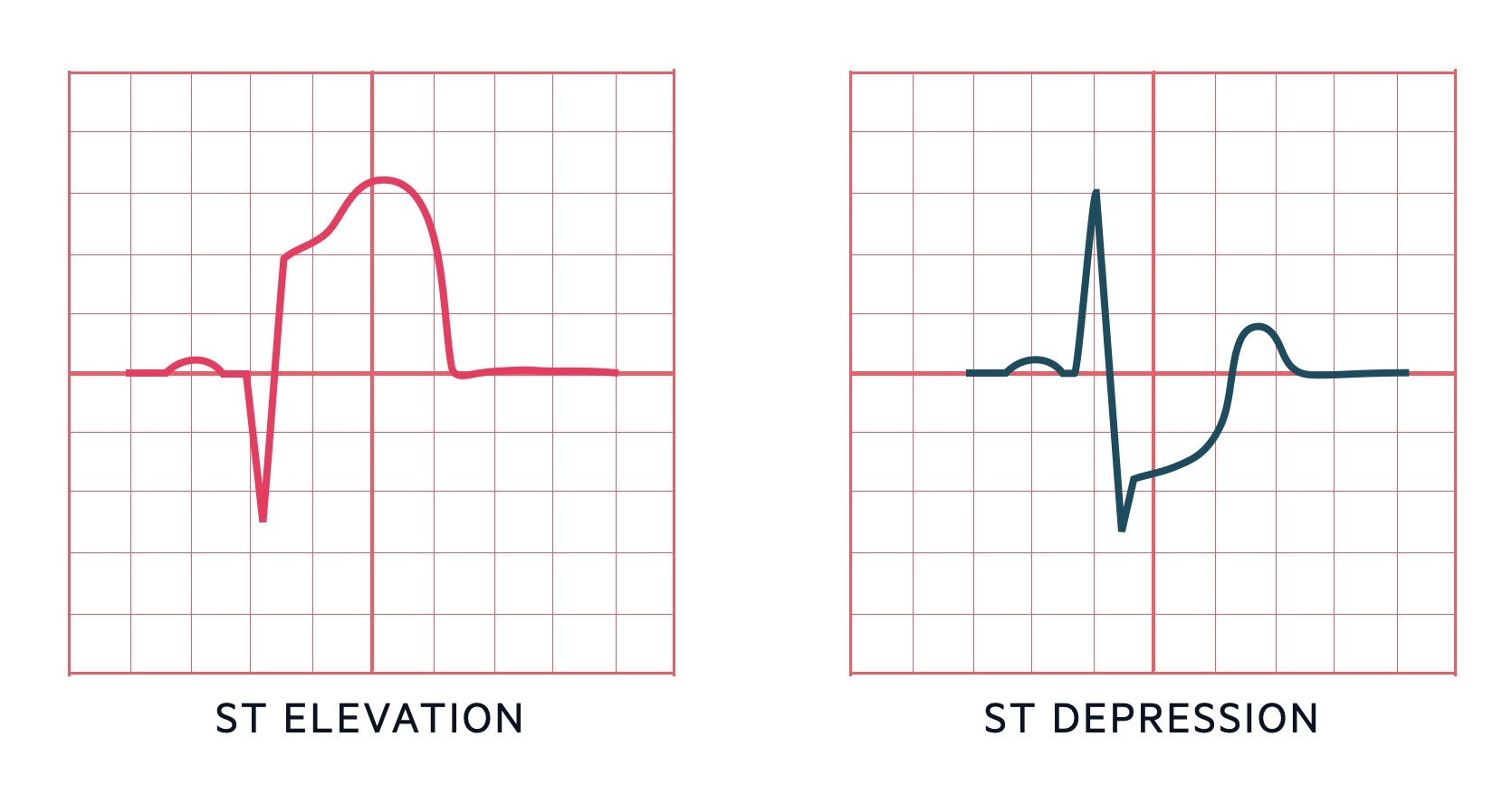

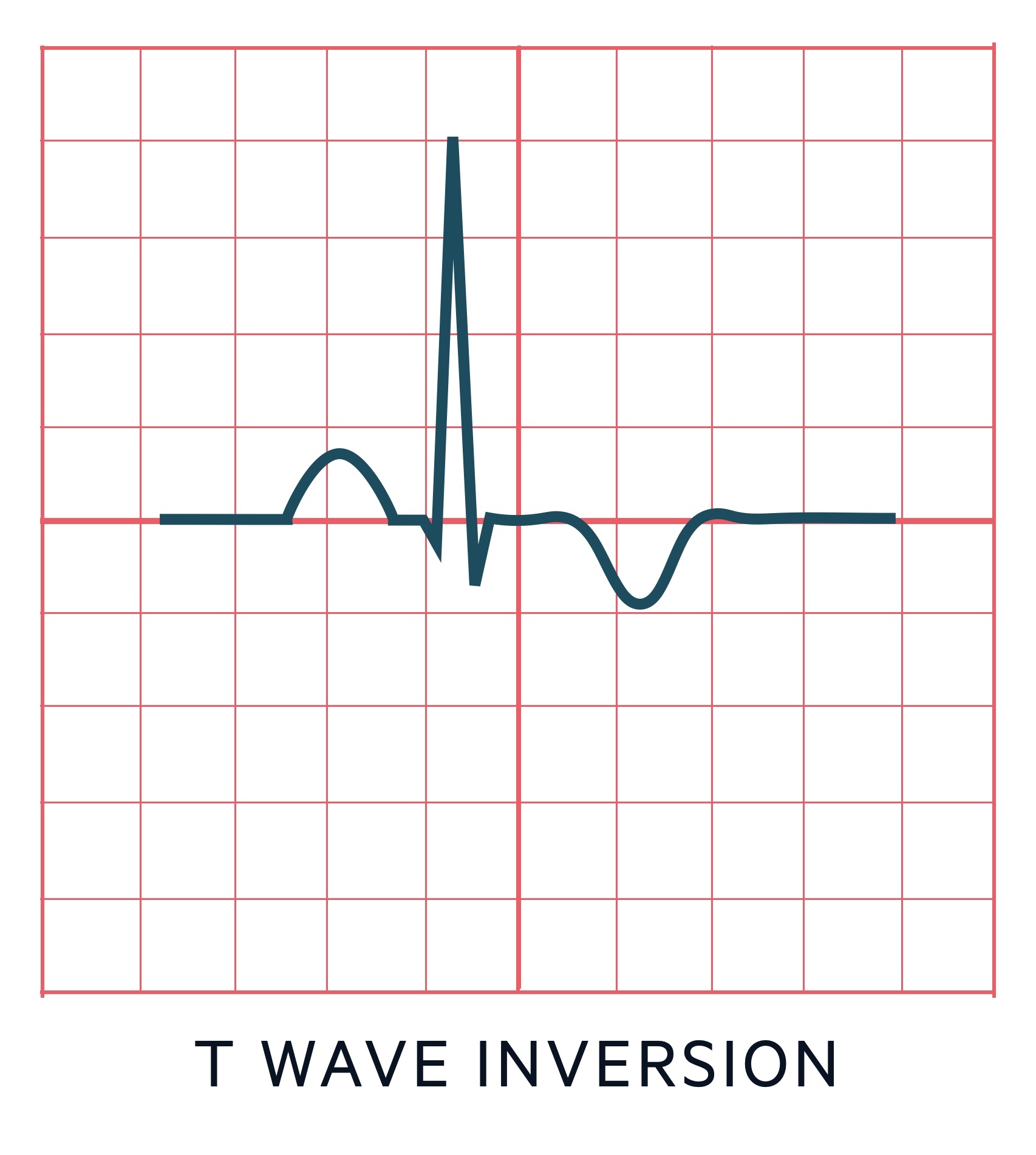

On an ECG, there are three main features of ischaemia:

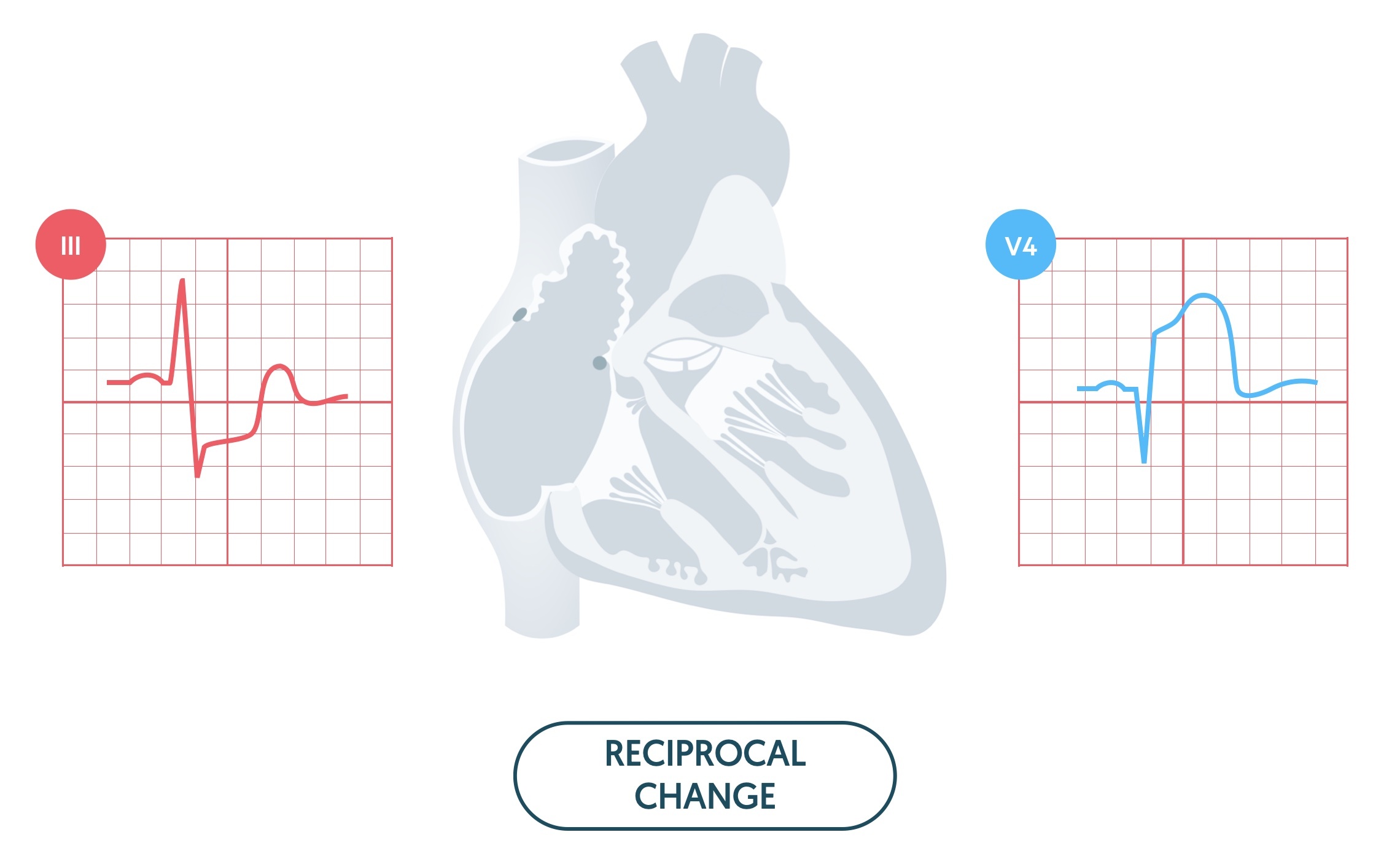

- ST elevation: seen in STEMI, may be evidence of reciprocal ST depression

- ST depression: more specific sign of ischaemia than T wave changes. Seen in NSTEMI/UA. Also seen as reciprocal change with ST elevation

- T wave inversion: less specific sign of ischaemia. Multiple causes. Seen in NSTEMI/UA and as part of the natural evolution of a STEMI over days.

ST changes

Two predominant abnormalities of the ST segment can occur: elevation and depression

- ST elevation: movement of the segment upwards. May occur due to acute myocardial ischaemia or pericarditis. Other causes can include coronary vasospasm, benign early repolarisation, bundle branch block and ventricular aneurysm.

- ST depression: movement of the segment downwards. May occur due to acute myocardial ischaemia or as a reciprocal change to ST elevation. Other causes can include electrolyte disturbances, digoxin effect and bundle branch blocks.

T wave changes

T wave inversion may be a feature of myocardial ischaemia, even in the absence of ST changes. T wave inversion generally relates to the territory of the coronary artery affected by ischaemia.

T wave inversion may be fixed, which is usually associated with a previous ischaemic event and associates with Q waves. Alternatively, T wave inversion may be dynamic, which is associated with& acute myocardial ischaemia.

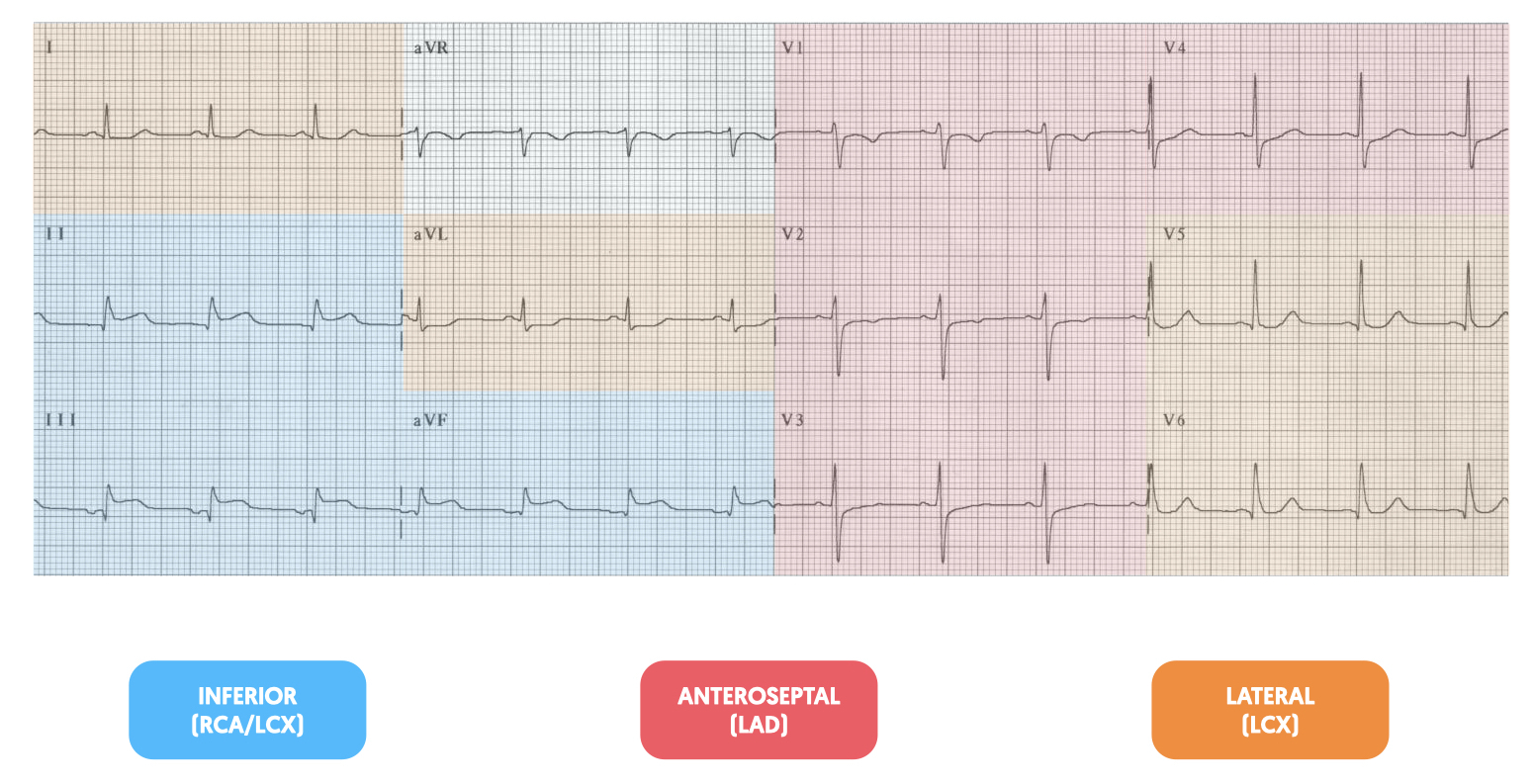

12-lead ECG

An acute STEMI typically presents with ST elevation of varying morphology. The ECG criteria for a STEMI is broadly defined as a ≥2 mm ST segment elevation in 2 contiguous chest leads or ≥1mm ST segment elevation in 2 contiguous limb leads (there may be slightly different variations of these ECG definitions based on age and sex).

The ST elevation usually occurs alongside Q waves and will occur in the leads that represent a coronary artery vessel territory:

- Anteroseptal STEMI: V1-V4

- Lateral STEMI: V5-V6, I, aVL

- Inferior STEMI: II, III, aVF

- Posterior STEMI: no ST elevation on routine ECG. Dominant R wave V1. May be ST elevation by placing posterior leads V7-V9.

During a STEMI, there are usually reciprocal changes. This refers to ST depression in the leads opposite those with ST elevation. Typical examples:

- Anterolateral STEMI: inferior ST depression (II, III, aVF)

- Lateral STEMI: inferior ST depression (II, III, aVF)

- Inferior STEMI: lateral ST depression (aVL, I)

- Posterior STEMI: anterior ST depression (V1-V3)

Evolution of STEMI

A number of ECG changes may be seen during the natural evolution of a STEMI:

- Minutes to hours: hyperacute T-waves

- 0-12 hours: ST-elevation

- 1-12 hours: Q-wave development

- Days: T-wave inversion

- Weeks: T-wave normalisation and persistent Q-waves

Troponin

Cardiac enzymes are biomarkers of myocardial necrosis.

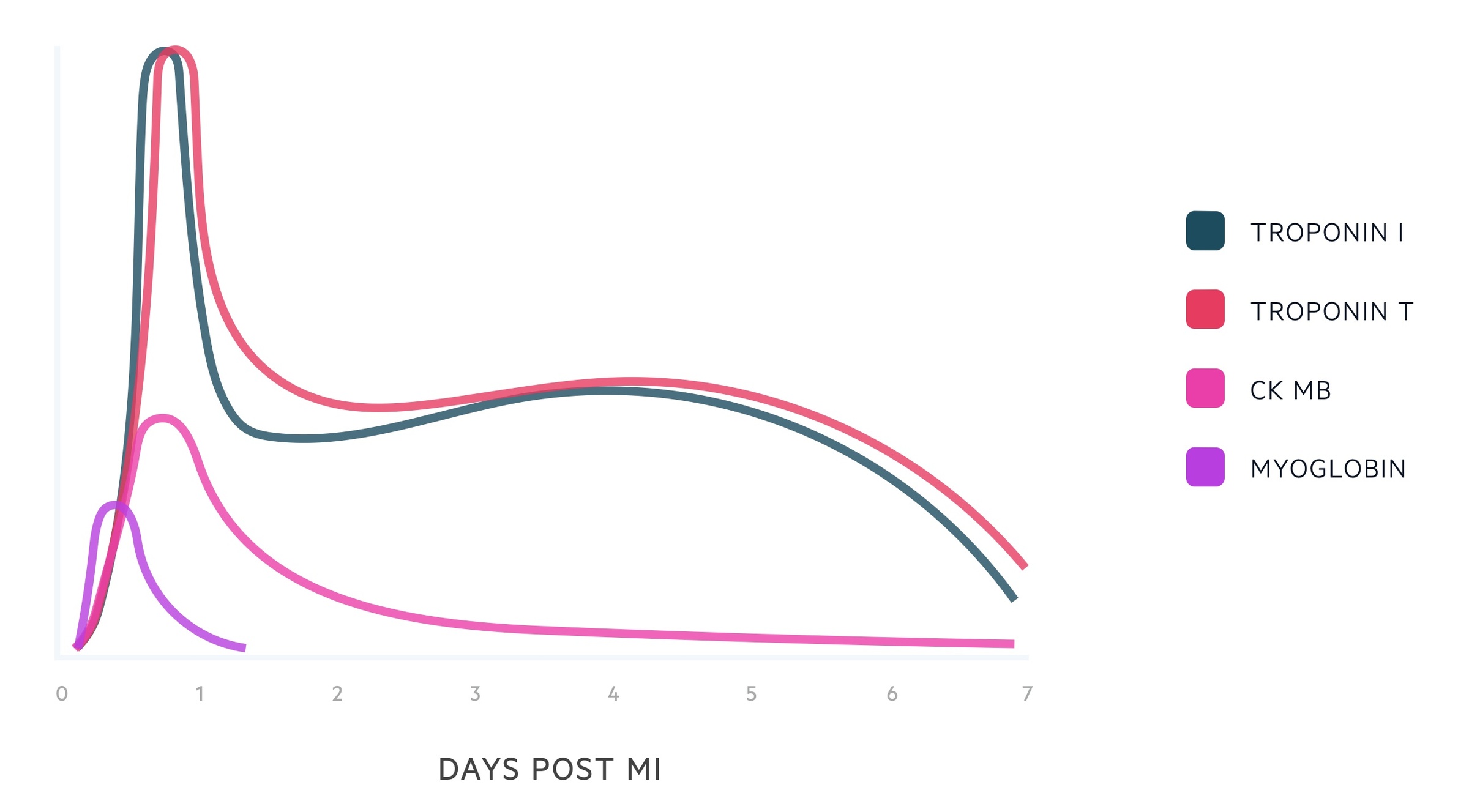

Traditionally, there are three types of cardiac enzymes that can be used to assess myocardial necrosis:

- Troponins (T or I)

- Creatine kinase (CK, specifically CK-MB)

- Myoglobin

These rise at different time points during the course of a myocardial infarction. The graph below shows the peak concentration against time for each biomaker following MI.

Troponin

Troponins (T or I) are the gold-standard test for the investigation for myocardial necrosis. They are now the only recognised biomarker that should be used in the diagnostic work-up of ACS. They begin to rise hours after the event.

Traditionally, troponin was measured 6-12 hours following a suspected myocardial infarction. However, with the use of newer ‘high-sensitivity‘ troponin assays, results can be achieved within 4 hours of patient presentation to emergency services. Troponin has an important role in ruling out ACS in patients with possible NSTEMI/UA. The negative predictive value for exclusion of acute MI with troponin is >95%, which increases to almost 100% with a second troponin at 3 hours.

Hospitals will have local guidelines on the use of troponin as part of a diagnostic algorithm to rule in or rule out ACS.

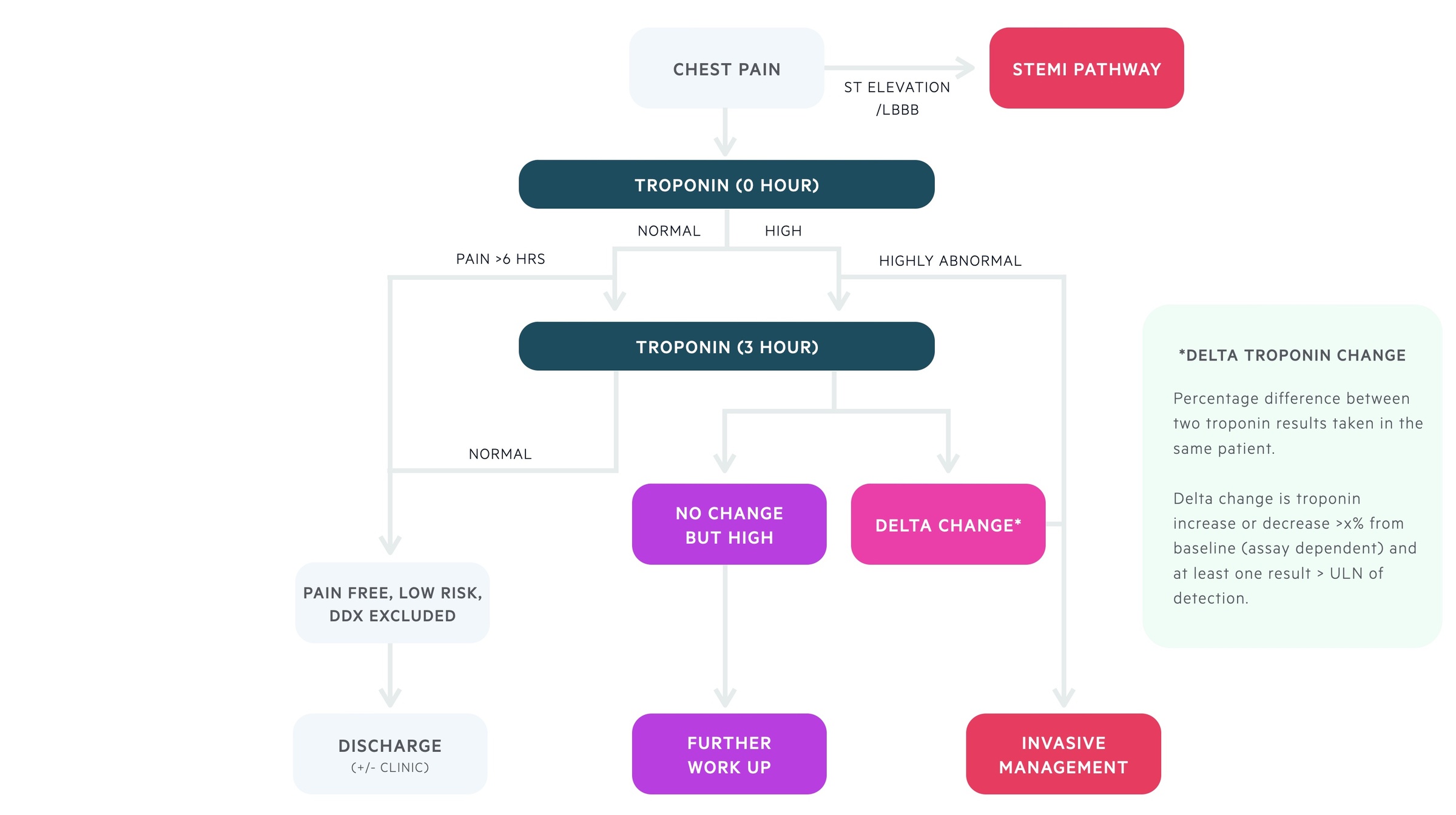

Diagnostic algorithm (0 hour / 3 hour)

When ruling in or ruling out ACS, you should always follow local hospital guidelines. The following flow diagram is based on the European Society of Cardiology 0 hour / 3 hour diagnostic algorithm.

LBBB – left bundle branch block / DDx – differential diagnosis / ULN – upper limit of normal / X% – percentage change (i.e. 50% or 30%). Depends on lab assay / Pain > 6 hours – Pain present more than 6 hours from presentation to emergency department

Other causes of troponin elevation

This refers to causes other than a plaque rupture type 1 myocardial infarction. These causes may relate to type 2 myocardial infarction with oxygen demand/mismatch, myocardial injury without evidence of ischaemia or multifactorial aetiologies.

- Tachyarrythmias

- Heart failure

- Hypertensive emergencies

- Critical illness (e.g. sepsis, burns)

- Myocarditis

- Cardiomyopathy (e.g. Takotsubo)

- Structural heart disease (e.g. aortic stenosis)

- Pulmonary embolism

- Renal dysfunction

- Coronary spasm

- Acute neurological event

Other investigations

Additional investigations are important in ACS work-up to look for co-morbidities, complications and any contraindications to treatments.

Bedside

- ECG: repeat ECGs important to look for dynamic changes

- Cardiac monitoring

- Blood pressure

- Capillary blood glucose

Bloods

- FBC

- U&Es

- LFTs

- TFT

- CRP

- Lipid profile

- Coagulation

- Group & save

- HbA1c

Imaging

- Chest XR – may demonstrate signs of heart failure

- Echocardiogram – may demonstrate reduced ejection fraction and / or valvular pathology. Also useful to look for regional wall motion abnormalities (RMWAs)

- CT pulmonary angiography – if pulmonary embolism is suspected or needs to be excluded

- CT angiography – if aortic dissection suspected or needs to be excluded

NOTE: RMWAs refer to regional abnormalities in the contractile function of the heart that should correspond to a coronary vessel.

Special

- Coronary angiogram – see management below

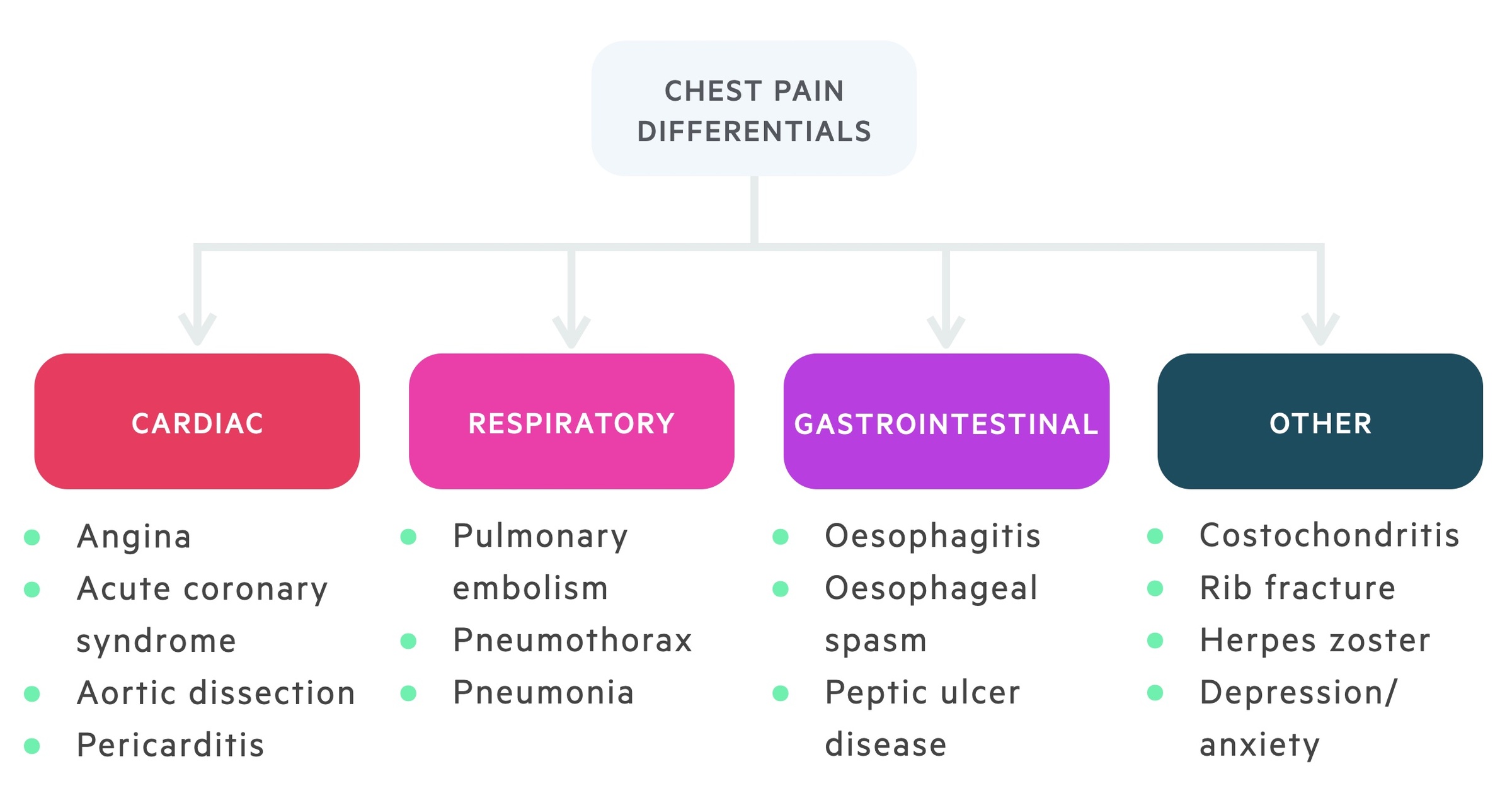

Differential diagnosis

There are numerous causes of chest pain, which should be considered in all patients.

The differential diagnosis of chest pain is best categorised by organ system into: cardiac, respiratory, gastrointestinal and other.

Remember, some of these differentials such as aortic dissection and pulmonary embolism can also be life-threatening conditions. It is important to have a low index of suspicion and investigate as necessary.

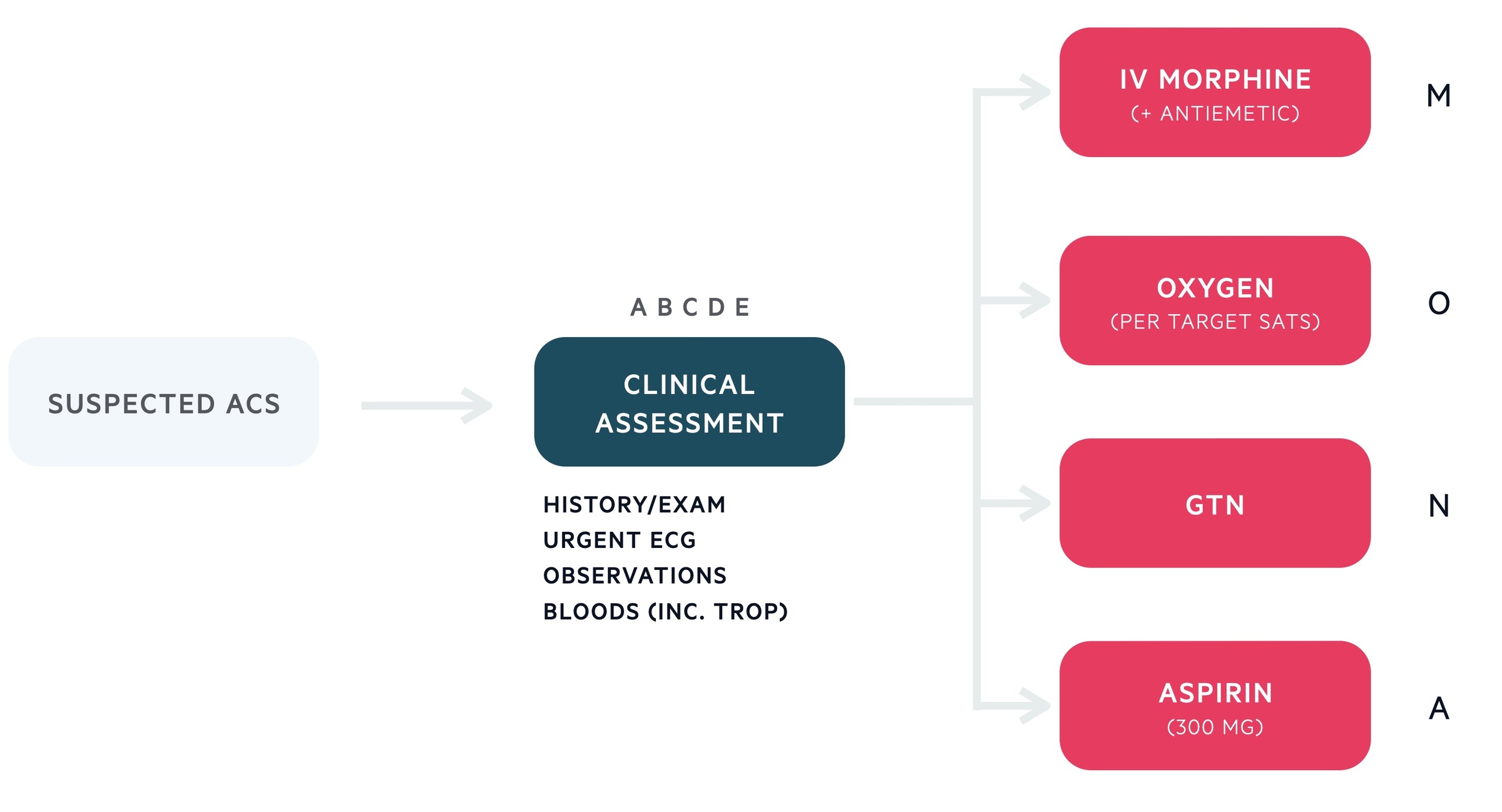

Immediate management

Immediate management of all patients with suspected ACS can be remembered using the mnemonic MONA – morphine, oxygen, nitrates, aspirin.

NICE guidelines recommend morphine (administered with an anti-emetic) in sufficient dosage to relieve chest pain, in addition to loading-dose aspirin (300mg) and sublingual (under the tongue) GTN, a potent vasodilator. Oxygen appears to be of limited benefit in patients with preserved oxygen saturations (94% or greater), and may indeed be harmful.

Oxygen should be reserved for patients if saturations <94% (European Society of Cardiology recommend <90%) and <88% in patients at risk of hypercapnic respiratory failure (target in these patients is 88-92%).

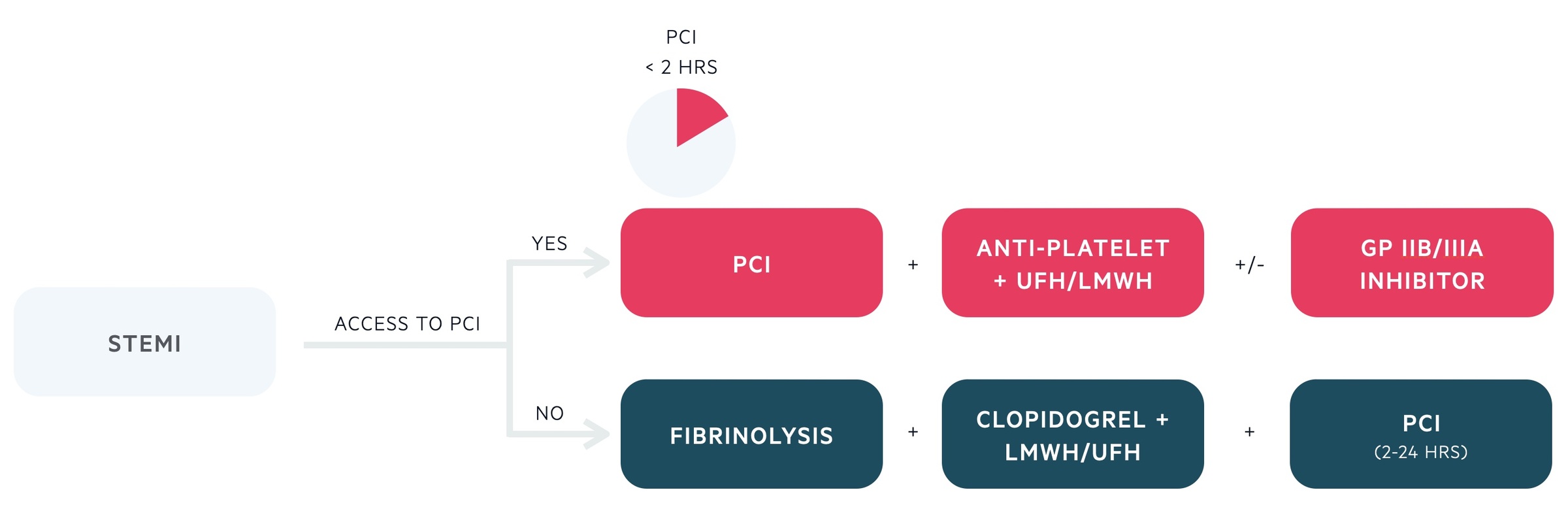

STEMI management

Patients with STEMI require emergency reperfusion to restore coronary flow and minimise myocardial injury.

Primary PCI

Patients diagnosed with a STEMI, who present within 12 hours of onset of chest pain, should be referred for emergency coronary angiography +/- primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). This should occur within 120 minutes of being diagnosed with ST elevation by a healthcare professional.

Coronary angiography involves insertion of a catheter via the femoral artery or radial artery. From here, the catheter can be passed to the coronary artery vessels with x-rays for guidance and contrast injected. The injection of contrast allows visualisation of the coronary anatomy. During the procedure a balloon catheter can be inserted to open up a blockage. A stent can be then be inserted into the blocked artery.

Fibrinolysis

If PCI is unable to be performed within 120 minutes then fibrinolytic agents should be considered (e.g. alteplase) while arranging transfer to a PCI centre. Coronary angiography +/- PCI should be performed in the following 2-24 hours after fibrinolysis and may be required more urgently if patients develop worsening symptoms (e.g. worsening pain, haemodynamic instability, cardiac arrest).

Anti-platelets

Patients should be initiated on aspirin and a second anti-platelet drug prior to PCI. This is usually ticagrelor 180 mg loading, following by 90 mg BD as a regular dose. Other options include clopidogrel (600 mg loading), particularly if there is a high bleeding risk, or Prasugrel (60 mg loading). The combination of aspirin and a second anti-platelet agent is referred to as dual anti-platelet therapy (DAPT) and this should be continued for 12 months post-PCI.

Antithrombotic agents

Patients with an acute STEMI should be offered antithrombotic therapy using unfractionated heparin or low molecular weight heparin (LWMH). This is usually given at the time of PCI. Additional agents including glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (e.g. tirofiban) may be given at the time of PCI in the presence of a high thrombus burden.

NSTEMI/UA management

Risk stratification is key to the management of patients with NSTEMI or UA.

Risk stratification

The GRACE, TIMI and HEART scores are all risk stratification tools that can be used to determine the risk an individual has of having a major cardiac event (e.g. MI or death) within a defined period of time. These scores are commonly used in the emergency department to help guide management in patients presenting with chest pain where ACS is suspected.

The NICE clinical guidelines on the management of unstable angina and NSTEMI (CG94) was last updated in 2013. This recommends the use of the GRACE score. HEART is a newer scoring system that has been incorporated into many local hospital guidelines. GRACE and HEART have been shown to better risk stratify patients with suspected NSTEMI/UA compared to TIMI.

- GRACE (Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events): estimates six-month mortality risk in patients with NSTEMI / UA. Divides patients from lowest (≤1.5%) to highest >9.0%).

- HEART (History, ECG, Age, Risk factors and Troponin): estimates six-week risk of major cardiac event (AMI, PCI, CABG, death) in patients with NSTEMI / UA.

- TIMI (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction): estimated 14 day all-cause mortality in patients with NSTEMI / UA.

Pharmacological management

The principle pharmacological agents to treat NSTEMI / UA include:

- Additional antiplatelet agent (e.g. clopidogrel, ticargrelor)

- Antithrombotic agent (e.g. fondaparinux, UFH)

All patients with a GRACE risk stratification score >1.5% should be treated with dual anti-platelet therapy. This means loading patients with 300 mg clopidogrel (lower dose if not immediately for coronary angiography +/- PCI) followed by 75 mg daily. Optimal dosing may depend on local guidelines.

In addition, bleeding risk should be assessed and if there are no overt contraindications, patients should be initiated on antithrombotic therapy. The antithrombotic therapy of choice in fondaparinux 2.5 mg subcutaneously once daily. Alternatively, if patients are planned for coronary angiography within the next 24 hours, unfractionated heparin can be used (this should be guided by local cardiology guidelines).

Patients deemed low risk can be initiated on aspirin only (as part of initial management) whilst awaiting further investigations. Patients should be subsequently initiated on DAPT and fondaparinux if:

- Significant delta change in troponin

- Worsening/recurrent ischaemic pain

- Deterioration (e.g. cardiogenic shock, arrhythmia, dynamic ECG changes): advisable to liaise with cardiology

Invasive coronary angiography

In patients very high risk, coronary angiography would be appropriate immediately and urgent discussions should be had with cardiology. This includes the following patients:

- Cardiogenic shock

- Pain refractory to medial therapy

- Life-threatening arrhythmia or cardiac arrest

- Mechanical complication (e.g. valve rupture)

- Acute heart failure with refractory angina

- Recurrent dynamic ECG changes (esp. brief ST elevation)

In patients who are intermediate-to-high risk (>3%), coronary angiography should be completed within 96 hours of hospital admission. The European Society of Cardiology recommend within 24 hours if the presence of a high-risk feature (e.g. delta troponin change, dynamic ST-T wave changes, GRACE score >140).

Low risk

In patients low risk, coronary angiography can be considered if there is evidence of recurrent pain or deterioration (e.g. heart failure).

In the absence of these, further invasive management should be considered following non-invasive testing for ischaemia. This can include:

- Transthoracic echocardiography: assessing for evidence of ischaemia (e.g. RWMAs, LV dysfunction). Also useful to investigate alternative pathologies.

- Stress echocardiography: can be considered if negative troponins, normal ECG and chest pain free for several hours.

- Cardiac MRI: can assess both perfusion and wall motion abnormalities. Able to detect recent infarction and assess for previous scars.

- CT coronary angiography: good at excluding coronary artery disease by visualisation of coronary anatomy.

Treatment summary

The management of patients with NSTEMI or UA can be remembered using the mnemonic BATMAN

- B – Beta-blockers (unless contraindicated)

- A – Aspirin (300 mg loading, then 75 mg once daily)

- T – Ticagrelor (180 mg loading, then 90 mg twice daily), alternatively clopidogrel if high bleeding risk

- M – Morphine (titrate for analgesia)

- A – Antithrombotic agent (Fondaparinux 2.5 mg subcutaneous unless contraindicated)

- N – Nitrates (sublingual nitrates to relief pain – consider infusion if ongoing pain)

GRACE scoring

GRACE (Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events) is a scoring system which estimates six-month mortality risk in patients with NSTEMI / UA.

The GRACE score is calculated by clinicians by entering simple clinical risk factors into a web-based model.

GRACE Scoring – ACS Risk Score

- Age

- Heart rate

- Systolic BP

- Creatinine

- Killip class

- ST-segment deviation

- Cardiac arrest at admission

- Abnormal cardiac enzymes

A full calculator can be found on MDCALC

Long-term management

Long-term management requires both medical therapy and patient education.

Modifiable risk factors

All patients should be advised to address modifiable risk factors, which include:

- Smoking cessation

- Dietary changes

- Exercise

- Reduce alcohol consumption

Travel & sex

All patients who drive should be advised to check DVLA guidelines on driving. If they are wishing to fly they should seek advice from the UK civil aviation authority. Finally, given no significant complications related to their MI, they can usually resume normal sexual activity within four weeks.

Pharmacological agents

Following an MI, several medications should be initiated to help in the secondary prevention of major cardiovascular events and to help prevent abnormal remodelling of the heart.

- Dual anti-platelet therapy (e.g. aspirin and clopidogrel): should be continued for one year. Vital if had PCI to prevent in stent thrombosis.

- Beta-blockers (e.g. bisoprolol)

- High dose statin (e.g. atorvastatin 80 mg)

- ACE inhibitor (e.g. ramipril). Angiotensin receptor blocker can be an alternative if side-effects or intolerant to ACE inhibitor)

- Consider mineralocorticoid antagonist: reserved for patients with LV dysfunction (i.e. heart failure) following MI.