Key facts

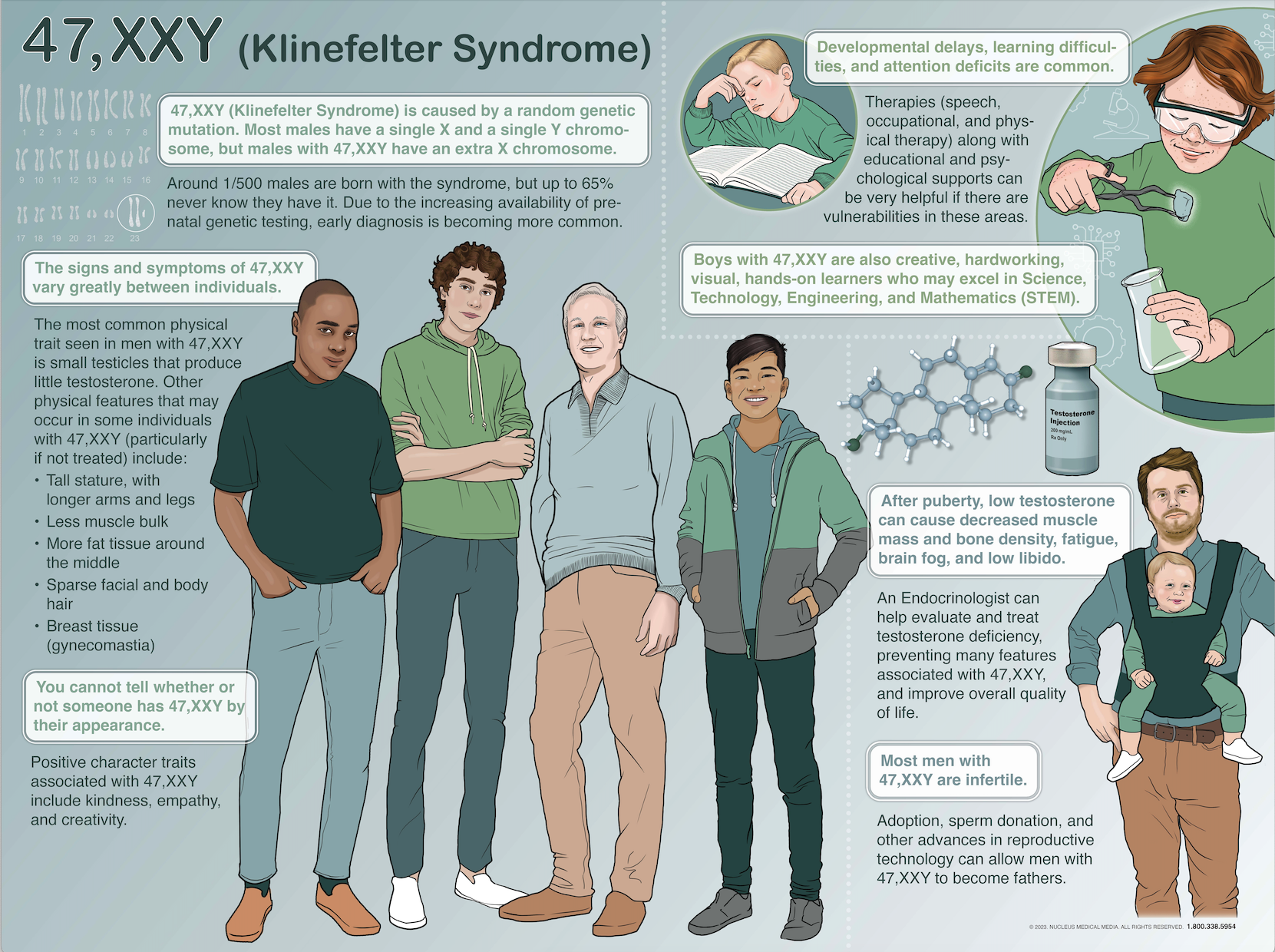

- Klinefelter syndrome is a congenital (from birth) condition, where males are born with one or more extra X chromosomes.

- Young children with Klinefelter syndrome can have motor and language delay, as well as learning and behavioural problems.

- Adolescents and adults with Klinefelter syndrome may notice that they have a small penis and testicles, less facial and body hair and larger breasts than expected.

- Many people with Klinefelter syndrome don’t know they have it and have never received treatment.

- Testosterone therapy, usually started at puberty, can help with many of these features of Klinefelter syndrome.

What is Klinefelter syndrome?

Klinefelter syndrome is a congenital (from birth) condition in which males are born with one or more extra X chromosomes. It is not inherited. Klinefelter’s syndrome is also know as XXY syndrome.

Klinefelter syndrome is common, affecting 1 in every 500 to 1000 males born in Australia each year. But most people with Klinefelter syndrome don’t know they have it and have never received treatment.

Males with Klinefelter syndrome are unable to produce enough of the male hormone, testosterone, for the body’s needs. Low levels of testosterone affect the development of male characteristics. The extra X chromosome also affects the ability to produce sperm. Males with this condition are usually infertile, as they often don’t have any sperm in their ejaculate (this is known as ‘azoospermia’).

What causes Klinefelter syndrome?

Most males have one X and one Y sex chromosome. Klinefelter syndrome occurs when a male baby is born with one or more extra X chromosomes. This is the result of a random genetic error that happens during the formation of the egg or the sperm, or it can happen after conception. It is not clear why this happens.

While Klinefelter syndrome is genetic, it is not inherited. The likelihood of having another pregnancy affected by Klinefelter’s syndrome is extremely low.

What are the symptoms of Klinefelter syndrome?

Most males with Klinefelter syndrome lead normal lives. Some people are affected only very mildly, while for others, it has a major impact on their lives. Most babies with Klinefelter syndrome do not have noticeable symptoms.

Children with Klinefelter syndrome might have:

- difficulties with walking or talking

- slow language and speech development, learning or behavioural difficulties

- emotional immaturity

- poor muscle tone

Sometimes, issues first appear at puberty. If you have Klinefelter syndrome, you don’t experience the same rise in testosterone that other males have at puberty. You might notice that you have:

- a small penis and small testes

- less hair on your face and body

- breasts that are a bit bigger than expected

You might also feel a bit different, which can bring about its own problems. You may also be tall for your age.

Some males don’t realise they have Klinefelter syndrome until they experience fertility problems. Some may never find out.

How will I be diagnosed with Klinefelter syndrome?

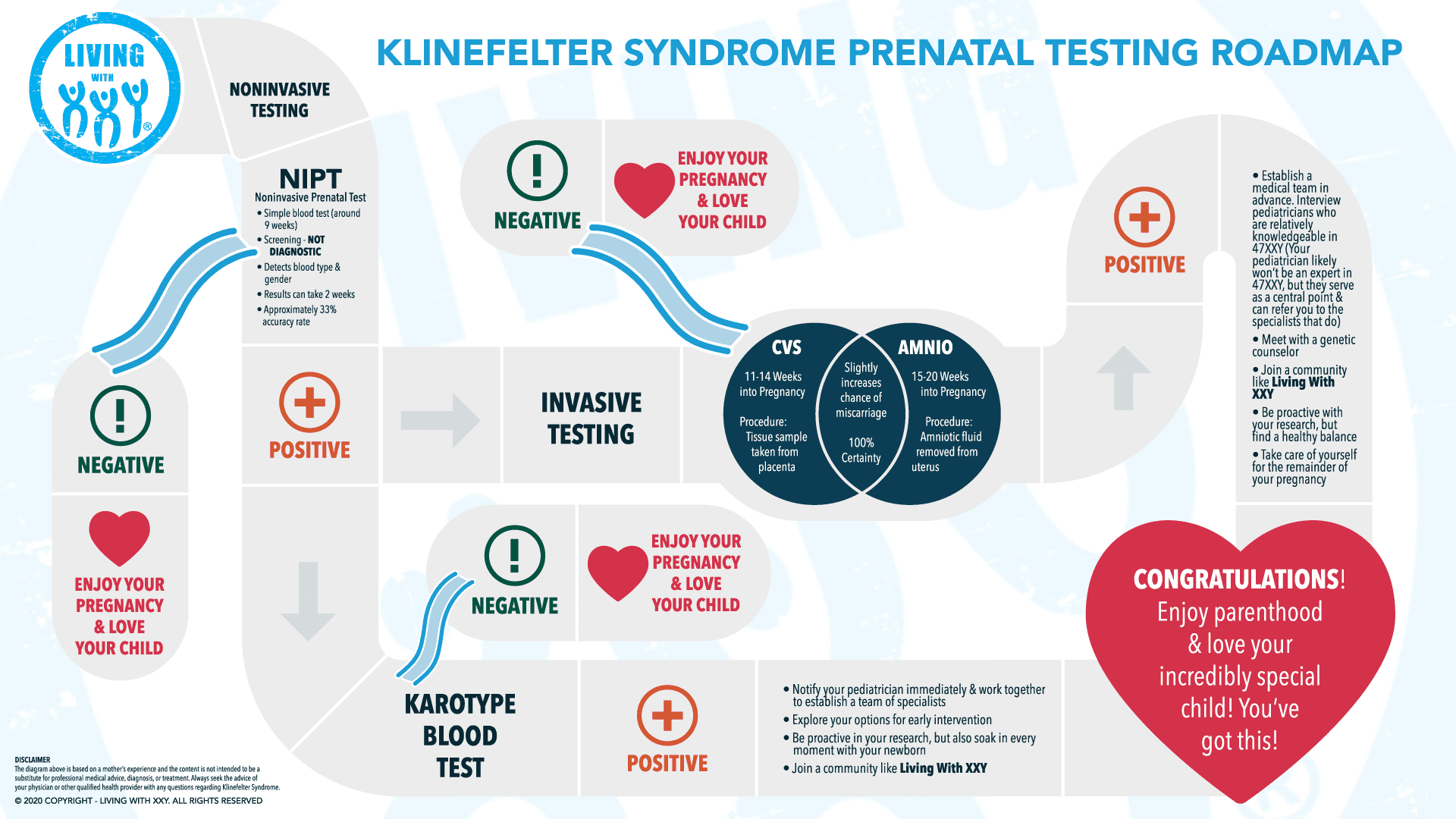

Klinefelter syndrome is diagnosed with blood tests. Your doctor may recommend a blood test called a karyotype, which is a genetic test that looks at your chromosomes. If you have more than one X chromosome in your karyotype test, you have Klinefelter syndrome.

How can Klinefelter syndrome affect my health?

Most males with Klinefelter syndrome have a normal sex life but are infertile. If you have Klinefelter syndrome, you are at higher risk than other males of developing:

- osteoporosis

- diabetes

- some cancers

- autoimmune diseases such as hypothyroidism

- psychological problems that come about from feeling different

How will I be treated for Klinefelter syndrome?

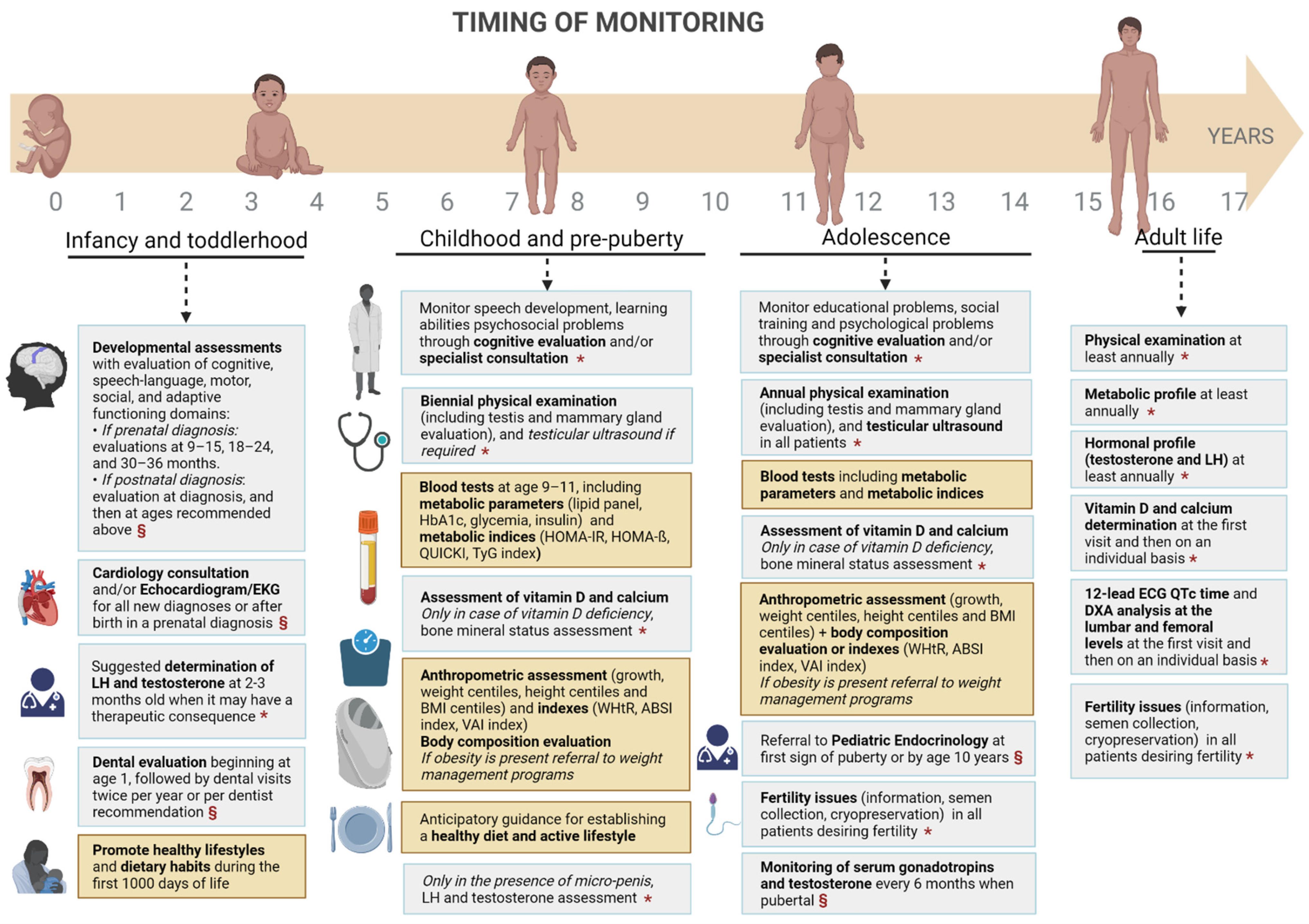

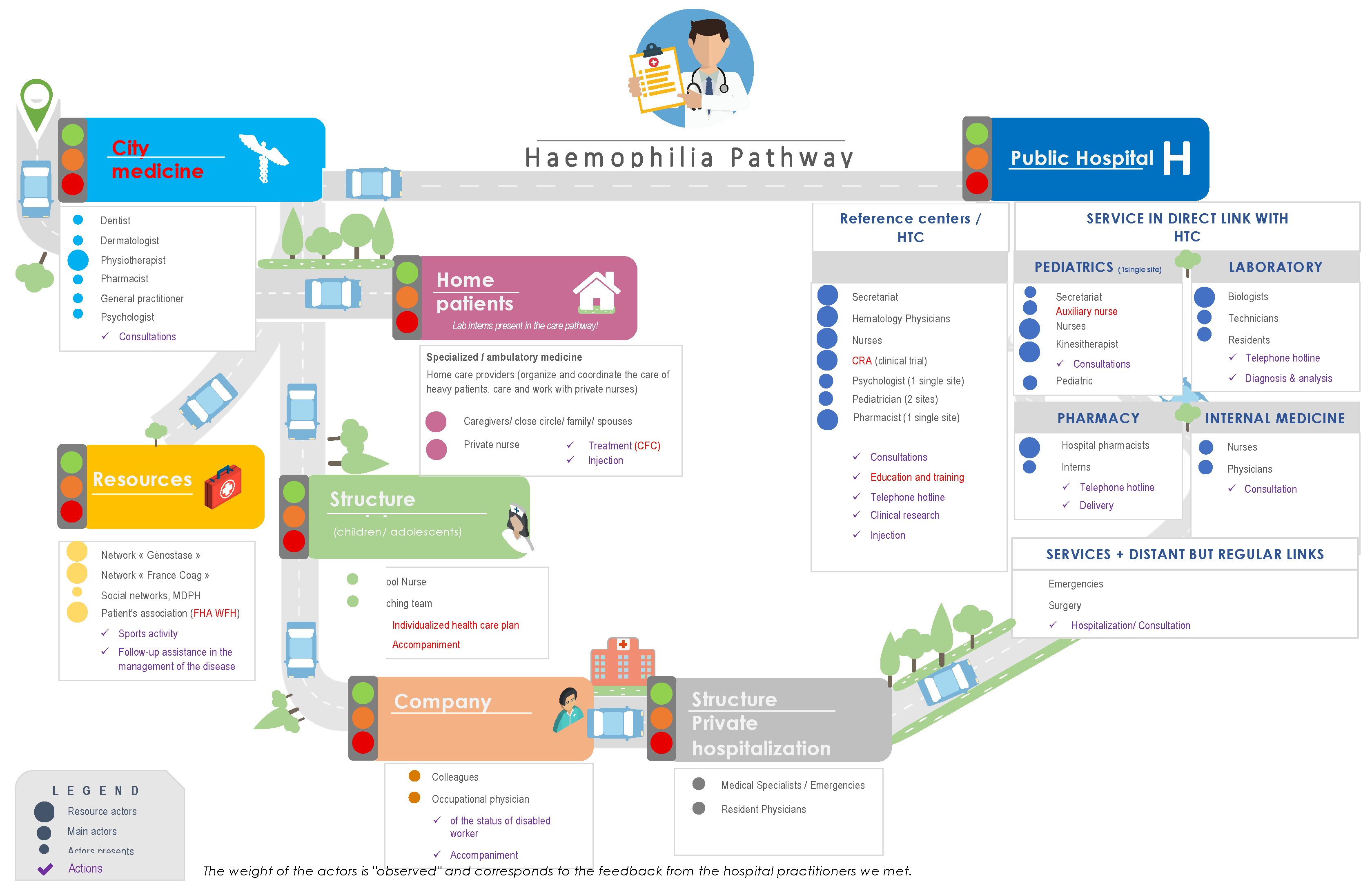

Children with Klinefelter’s syndrome should be seen by their doctor at least every 2 years to monitor their physical development. Many children with Klinefelter’s may require specialist support to help with speech, learning, behaviour or psychiatric issues.

Testosterone therapy can help with many of the symptoms of Klinefelter syndrome. This treatment should begin at puberty or as soon as possible after puberty begins.

If you have Klinefelter syndrome and are not able to conceive a child naturally, you may be able to use assisted reproductive technologies, such as new forms of in-vitro fertilisation (IVF). For example, if you have a very low sperm count, a single sperm may be injected into an egg (called intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection or ICSI) to increase your chance of conceiving. Speak with your doctor, who may refer you to a fertility expert to advise you on this.

Counselling and psychological therapy may also help you cope with emotional difficulties.