Overview

Headache is a very common clinical presentation.

Headache refers to pain felt in any region of the head, which also includes behind the eyes and ear or in the upper neck. It is an extremely common presentation and can be broadly divided into primary headaches and secondary headaches.

- Primary headaches: a headache not caused by or attributed to another disorder. In other words, the headache itself is the primary disorder. Examples include tension-type headache, migraine, and cluster headache

- Secondary headaches: a headache caused by another underlying disorder. In other words, the headache is a symptom of another pathological process. Examples include subarachnoid haemorrhage and meningitis

The presentation of headache represents 2% of all emergency department admissions. It is vital to be able to differentiate benign primary headaches from other life-threatening causes of headaches based on clinical assessment. Remember that while neuroimaging (e.g. CT or MRI head) can be extremely useful in headaches, a thorough history, and clinical examination are the most important parts of the patient interaction.

Differential diagnosis

There is a wide differential diagnosis for the presentation of headaches.

The causes of headache can be broadly divided by the timing of onset:

- Acute headaches: over seconds to hours

- Subacute headaches: overs hours to days

- Chronic or recurrent headaches: over weeks to months

Acute headaches

Several life-threatening conditions can present with an acute-onset headache. It is important that these are differentiated from an acute presentation of a benign primary headache such as a migraine.

- Subarachnoid haemorrhage: a bleed into the subarachnoid space. Commonly due to a ruptured aneurysm. Classically causes a ‘thunderclap headache’ with maximal intensity within a few seconds to under one minute. Often described as being ‘hit on the back of the head’. May be associated with loss of consciousness, neck pain, nausea, vomiting and/or photophobia.

- Intracerebral haemorrhage: this is a type of stroke due to a bleed into the brain parenchyma. Typically causes a sudden onset headache and there may be a history of anticoagulation use. Can cause focal neurological deficits (e.g. hemiplegia) depending on the location of the bleed. Associated with other global neurological features such as reduced consciousness, seizures, nausea and/or vomiting.

- Migraine: a primary headache that typically causes a unilateral, throbbing headache associated with phonophobia, photophobia and nausea/vomiting. May be associated with an aura (i.e. fully-reversible visual, sensory or other central nervous system symptoms). Typically last 4-72 hours.

- Trauma (and associated injuries): a head injury can lead to a localised on generalised headache and may present weeks after the trauma due to a secondary complication (e.g. subdural haematoma). Can cause coma or decline in mental status due to associated bleed (e.g. extradural, subdural or subarachnoid haemorrhage).

- Arterial dissection: this refers to a tear within the arterial wall lining (i.e. intima). A headache with neck pain or pain that radiates into the neck may be suggestive of carotid or vertebral dissection. Usually a history of trauma (even if minor). Depending on the extent of the dissection stroke/TIA symptoms may occur whereas others have an isolated headache/neck pain. An isolated, painful Horner’s syndrome (miosis, ptosis) is classic for carotid artery dissection due to the location of the sympathetic fibres around the carotid artery.

- Cerebral venous thrombosis: occurs due to a thrombus within one of the major veins of the head. The presentation is highly variable, but classically seen in those with thrombosis risk (e.g. inherited thrombophilia, pregnancy). Features depend on the location but can include seizures, focal neurological deficits and papilloedema.

- Meningitis: refers to an infection of the meninges. Can be life-threatening if bacterial. Acute meningitis should always be suspected in a patient with a global acute headache, neck stiffness, fever and photophobia. The combination of headache, neck stiffness and photophobia is known as meningism.

- Spontaneous intracranial hypotension: this refers to a sudden onset headache on sitting or standing. May be associated with other neurological features and thought to occur due to a cerebrospinal fluid leak in the spine. Typically resolves with lying flat.

- Acute angle-closure glaucoma: this is an ophthalmic emergency that develops due to blockage of the drainage of the aqueous humour within the anterior chamber of the eye. Causes a rise in intra-ocular pressure, severe eye pain, and headache. Visual disturbance is commonly seen.

Remember, there are many other causes of an acute headache such as post-coital headache, hypertensive emergencies, post-LP headache or even carbon monoxide poisoning.

Subacute headaches

Some causes of headaches may develop over hours to days. Just remember, many of the causes of an acute headache may actually lead to a subacute presentation so don’t be caught out. Classic causes of a subacute presentation include:

- Giant cell arteritis: this is a type of large-vessel vasculitis with preferential involvement of the carotid artery and its branches. Classically causes a unilateral temporal headache in older patients with scalp pain, jaw claudication and visual changes. Without urgent steroids can lead to permanent visual loss.

- Brain abscess: this refers to a localised area of infection within the brain parenchyma. May be features of recent bacteraemia, infective endocarditis or head/neck infection (e.g. otitis media). Focal neurological deficits may be present that depend on location and fever may be noticed but often absent.

- Space occupying lesions: a progressive headache with other features of raised intracerebral pressure (ICP) that include worse on lying down, bending over, straining or in the early morning. May be a primary brain tumour or metastatic spread from another cancer (e.g. lung cancer). Papilloedema (swollen optic discs) is usually present and may have focal neurological deficits related to the location of the lesion. With a severe rise in ICP, may have features of abnormal consciousness, nausea and vomiting.

- Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH): a disorder caused by chronically elevated ICP, which leads to the characteristic clinical features of global headache, papilloedema, and visual loss. It is a high-pressure headache worse on lying down and bending over and usually seen in overweight individuals.

Chronic or recurrent headaches

Primary headaches are common causes of chronic or recurrent headaches.

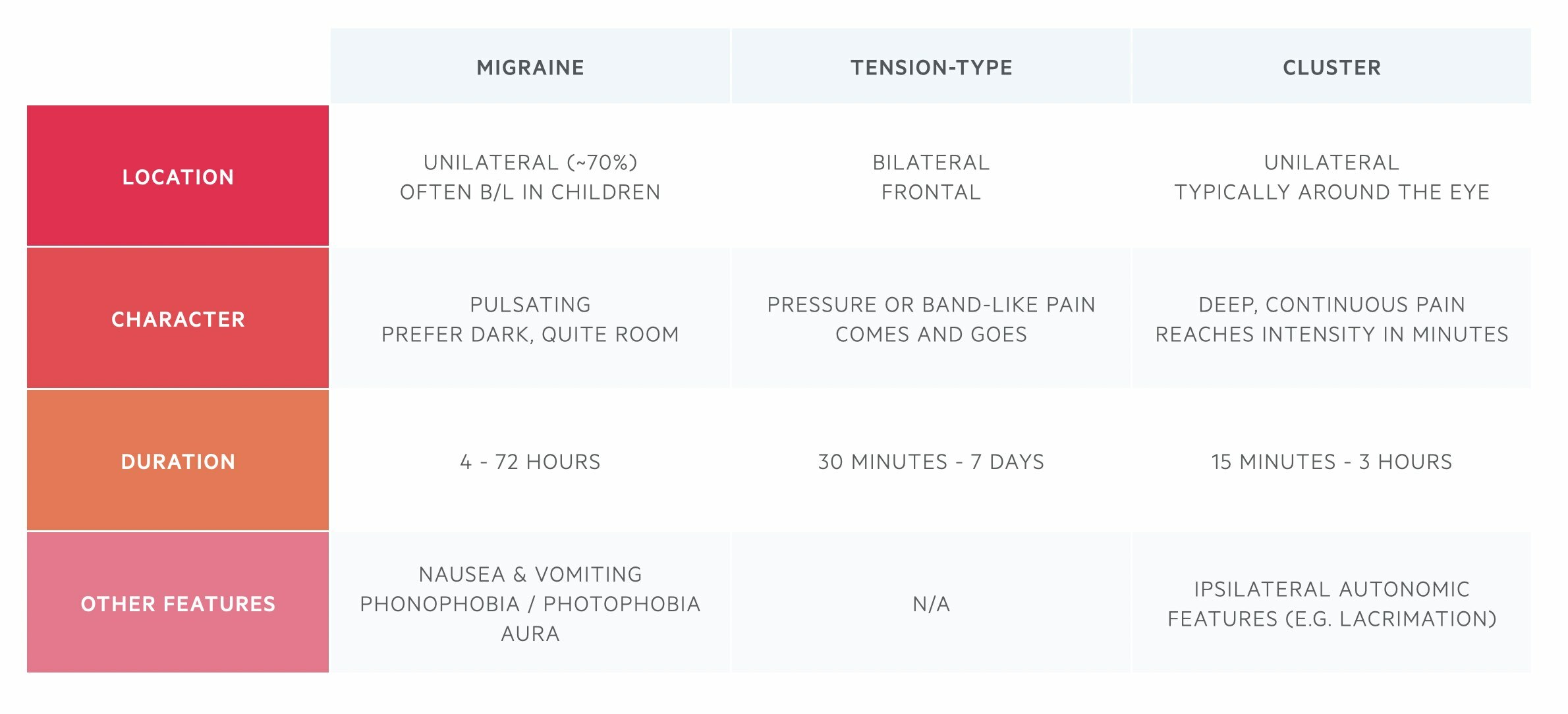

- Tension-type headache: an infrequent, episodic headache that is described as bilateral with a pressing/tight sensation of mild-moderate intensity. They last minutes to days. Not associated with other features (e.g. nausea, photophobia)

- Migraine: a primary headache that typically causes a unilateral, throbbing headache associated with phonophobia, photophobia and nausea/vomiting. May be associated with an aura (i.e. fully-reversible visual, sensory or other central nervous system symptoms). Typically last 4-72 hours.

- Cluster headache: this is typically described as a unilateral headache centred over the eye or temporal region that causes short attacks (15-180 minutes) with ipsilateral autonomic signs (e.g. conjunctival injection, nasal congestion). It may be episodic (80-90%) with periods of remission or chronic (no periods of remission > 3 months).

- Other trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias: these are a group of unilateral headaches that are accompanied by ipsilateral cranial autonomic symptoms (e.g. miosis, lacrimation, rhinorrhea, nasal congestion). They include cluster headache (see above), Paroxysmal hemicrania (attacks 2-30 minutes, duration 5-40 daily), SUNCT/SUNA (attacks 1 second to 10 minutes, duration 1-200 daily), and Hemicrania continua (attacks months to years, duration continuous).

- Cervical spondylosis: generally refers to osteoarthritis or degenerative spinal changes in the neck. Often associated with neck pain and headaches typically start at the back of the head and radiate over the top to the forehead.

- Medication overuse headache: this is a type of chronic headache due to overuse of analgesia taken for symptomatic relief of a headache.

- Sinusitis: Infection within the sinuses of the facial bones. This is an uncommon cause of recurrent headache

- Space occupying lesions: a progressive headache with other features of raised ICP that include worse on lying down, bending over, straining or in the early morning. May be a primary brain tumour or metastatic spread from another cancer (e.g. lung cancer). Papilloedema (swollen optic discs) is usually present and may have focal neurological deficits related to the location of the lesion. With a severe rise in ICP, may have features of abnormal consciousness, nausea and vomiting.

Primary headaches

Almost 90% of primary headaches are due to migraine, tension-type or cluster headaches. It is important to be able to accurately distinguish between these headache types.

History

A comprehensive history is the most important factor in establishing the cause of the headache and organising the right investigations.

There are many factors to consider in the assessment of headaches. These can include age, onset and timing, quality of the pain, aggravating and relieving factors, previous medical history and many others. We discuss the key factors to help differentiate the causes of a headache within the history.

Onset and timing

The onset of the headache is very important, especially in patients presenting with an ‘acute’ headache. Important things to establish include:

- What was the patient doing at the time? (e.g. spontaneous or trauma)

- How quickly did the headache reach maximum intensity? (e.g. within a few seconds or several days)

- Has the headache been persistent since onset or come and go?

It is important to recognise a ‘thunderclap’ headache that describes a headache that reaches maximum intensity within a few seconds or less than one minute. This type of headache is often described as ‘being hit over the head’ and may indicate a serious underlying pathology such as a subarachnoid haemorrhage.

Location

Many headaches will cause a non-specific generalised headache felt across all the regions of the head. However, some conditions are associated with headaches in very specific regions such as the temple, occipital region, or even frontal region.

It is firstly important to establish whether the headache is unilateral or bilateral.

- Unilateral: classic causes of a unilateral headache include giant cell arteritis, migraine, or cluster headaches

- Bilateral: this may be generalised or specific to a region such as a bilateral frontal headache in tension-type

The location of the headache is not very useful at differentiating between causes but some secondary causes of headache may have typical locations. Just note that these can cause headaches in other regions.

- Frontal headache: tension-type

- Temple headache: giant cell arteritis

- Peri-orbital headache: cluster headache or acute angle-closure glaucoma

Pain radiating from, or too, the neck and upper back may indicate meningeal irritation seen in subarachnoid haemorrhage or meningitis. It may also be seen in cervical spondylosis.

Associated features

Associated features refer to the constellation of other symptoms that can present alongside a headache. These are very useful for differentiating between the causes. Typical features include:

- Nausea and/or vomiting: commonly found in patients with migraine and form part of the diagnostic criteria. Also seen in patients with raised ICP (e.g. IIH, space-occupying lesion) and systemic illness (e.g. meningitis).

- Neck stiffness: a cardinal feature of meningeal irritation and may indicate meningitis or subarachnoid haemorrhage. Neck pain may also occur in arterial dissection or cervical spondylosis.

- Photophobia: this refers to a dislike for bright lights. A common feature of migraines and patients with meningeal irritation

- Phonophobia: this refers to a dislike for loud sounds. Another common feature of migraines

- Visual changes: changes can occur as part of an aura in migraine. Visual loss may occur in giant cell arteritis, acute angle-closure glaucoma or raised intracranial pressure. Cerebrovascular events or space-occupying lesions may affect the visual pathway leading to visual field defects.

- Focal neurological deficits: this refers to neurological signs and symptoms that localised to a specific area such as left-sided weakness or a cranial nerve defect. The findings depend on the location of the abnormality.

- Global neurology deficits: this refers to features consistent with global dysfunction of the brain. This is often due to raised intracranial pressure or severe infection. Features typically include altered mental status, seizures, and/or coma.

Exacerbating and relieving factors

This involves establishing what make the headache better and what makes the headache worse. It is important to determine whether there are any features of a low or high-pressure headache that refers to changes in intracerebral pressure:

- Low-pressure headache: worse on sitting or standing. Known as an orthostatic headache. Results from not enough CSF (e.g. a leak). Other features include dizziness, tinnitus, and visual changes.

- High-pressure headache: worse or lying down, bending over or straining. Typically worse in the early morning. May be associated with nausea, vomiting, visual changes and low consciousness (depending on acuity and severity). Results from any cause of a raised intracranial pressure (e.g. tumour, IIH, abscess).

Past medical history

Understanding a patients’ co-morbidities are vital to determine the possible cause of headache. A really key question is whether the patient has previously experienced headaches and how the current headache differs from those previous experiences. Headache is always concerning in a patient with no previous history, especially in the elderly.

Other parts of the medical history to think about include:

- Current or previous history of cancer: may suggest metastatic spread

- Any trauma: may indicate a bleed or fracture

- Any recent head and neck surgery: could suggest a tracking infection or abscess

- Any thrombosis risk: increased risk of cerebral venous thrombosis

- Drug history: is there an element of medication overuse headache?

- Family history: particularly around history of bleeding, subarachnoid haemorrhage or aneurysms

Red flags

There are several red flags that are essential to determine in the history that may indicate a serious underlying cause of headache that requires further investigation. These can be remembered by the mnemonic ‘HEADACHE PAINS’:

- H – Head injury (any history of trauma?)

- E – Eye pain +/- autonomic features

- A – Abrupt onset (i.e. thunderclap headache)

- D – Drugs (analgesia overuse or since new drug started)

- A – Atypical presentation or progressive headache

- C – Change in the pattern or recent-onset new headache

- H – High fever and systemic symptoms

- E – Exacerbating factors (worse on lying/standing, sneezing, coughing, exercise)

- P – Pregnancy or puerperium

- A – Age (onset > 50 years)

- I – Immunosuppressed (e.g. systemic therapy, HIV)

- N – Neoplasia (current or past history of cancer)

- S – Swollen optic discs (papilloedema)

Low-risk features

There are a number of features that act as indicators that the cause of headache is unlikely to be secondary to a serious underlying disorder. The presence of all these features is usually a good indicator that further investigations (e.g. imaging) are not required.

- Age ≤ 50 years

- Presence of typical features of primary headaches

- History of similar headache

- No abnormal neurologic findings

- No concerning change in usual headache pattern

- No high-risk comorbid conditions

- No new or concerning findings on history or examination

Examination

A full neurological examination is essential in patients presenting with a headache.

The neurological examination is important to look for major deficits in neurological function such as hemiparesis, gaze palsy, or low consciousness that suggest a serious underlying disorder. As part of the workup it is important to include the following:

- Blood pressure and pulse: hypertensive emergencies can cause acute headaches and late signs of raised intracerebral pressure include ‘Cushing’s reflex’ that refers to hypertension and bradycardia

- Palpate temporal arteries: the temporal arterial pulse is classically absent in temporal arteritis

- Examine the spine and neck muscles: look for any neck stiffness, features of cervical spondylosis, or any tender pressure points. Poor posture and repetitive movements can contribute to tension-type headaches and there is often pain and tenderness in the suboccipital muscles

- Cranial nerve examination: look for any cranial nerve neuropathies or lateraling neurological signs. For example, an isolated painful Horner’s syndrome may indicate an ipsilateral carotid artery dissection

- Peripheral neurological examination: look for any focal neurological deficits. This should include a gait assessment

- Ophthalmoscopy: important to look for any features of swollen optics discs that suggests raised intracranial pressure

Some of the major findings on clinical examination that would be considered high risk include;

- Focal neurological deficits

- Global reduction in consciousness

- Cranial nerve neuropathy

- Seizure activity

- Meningism (headache, neck stiffness, photophobia)

- Fever

- Presence of papilloedema

Investigations

Neuroimaging is an important part of the investigations into secondary headaches.

The history and examination are important because the likelihood of picking up pathology on imaging (e.g. CT or MRI head) is low in patients with no high-risk features. On the contrary, neuroimaging is essential in those with high-risk features such as a presentation with a ‘thunderclap headache’ or focal neurological deficit.

Bloods

Blood tests may be required depending on the suspected cause. In patients with suspected meningitis, bloods may show an elevation in inflammatory markers. In those who will need to undergo a lumbar puncture, it is important to assess clotting. CRP and ESR are critical in the evaluation of temporal arteritis.

Neuroimaging

Imaging of the brain is essential if a severe secondary cause is suspected such as subarachnoid haemorrhage, brain abscess or subdural haematoma. In general, those who present with an acute, severe headache will undergo a plain CT head without contrast initially because it is quick and easily accessible. Those with a chronic headache who require neuroimaging will usually be referred for an MRI because there is no radiation and it allows more detailed assessment. Other types of neuroimaging depend on the suspected aetiology.

Examples of possible imaging modalities include:

- CT head (without contrast): useful in acute situations to quickly screen for major pathology (e.g. bleeding, space-occupying lesion)

- CT head (with contrast): may be requested if there is a concern of a metastatic deposit or infective cause

- CT angiography: this uses contrast and assesses the cerebral vessels. Essential if there is concern about a vessel abnormality (e.g. dissection, aneurysm)

- CT venogram: this is utilised if there is suspicion of a cerebral venous thrombosis

- MRI head: provides a very detailed assessment of the brain and surrounding structures to assess for secondary causes of headache

Lumbar puncture

A lumbar puncture involves the insertion of a spinal needle into the subarachnoid space to take a sample of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The CSF can then be analysed for a variety of components to enable a formal diagnosis. Examples include:

- Subarachnoid haemorrhage: analyse for breakdown products of blood (e.g. bilirubin, xanthochromia)

- Meningitis: analyse for microscopy, culture and sensitivity with a viral PCR

- IIH: check the opening pressure, which will be elevated

Key tip

It is estimated that among patients who present to A&E with a ‘thunderclap headache’ only 8% will have a subarachnoid haemorrhage.

A ‘thunderclap headache’ describes a sudden onset headache where the maximal intensity of the headache is reached within a few seconds to less than one minute. It is a red flag headache that may indicate serious underlying pathology. This means that any ‘thunderclap headache’, even in a patient with a history of recurrent headache, must be taken seriously and investigated for a secondary cause.

The most concerning of these causes is a subarachnoid haemorrhage. However, other causes of a ‘thunderclap headache’ can include:

- Arterial dissection

- Cerebral venous thrombosis

- Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome

- Intercerebral haemorrhage

- Meningitis

- Pituitary apoplexy

Due to the number of serious causes that can induce a ‘thunderclap headache’ patients usually undergo cerebral imaging (e.g. urgent CT head) with or without preceding to lumbar puncture.