Overview

Lymphadenopathy essentially refers to lymph nodes with abnormal consistency or size.

Lymphadenopathy is a very broad term that simply refers to the disease of lymph nodes. The term is used to represent a change in size or consistency of a lymph node. The two most common causes of lymphadenopathy are infection and malignancy.

Lymphadenopathy may be peripheral or visceral:

- Peripheral: lymph nodes located in areas close to the skin that can be palpated when enlarged (e.g. neck, axilla, groin)

- Visceral: lymph nodes located inside the body at deep locations, usually in association with major organs (e.g. mesenteric lymph nodes, hilar lymph nodes)

Lymphadenopathy may be localised or generalised.

- Localised: enlarged lymph nodes affecting a single region (e.g. axillae)

- Generalised: enlarged lymph nodes affecting more than one region (e.g. inguinal and cervical)

The presence of lymphadenopathy may be a non-specific finding or indicate the need to look for a serious underlying cause. This largely depends on the actual size and consistency of the lymph node(s), the number affected, and the clinical presentation of the patient.

Lymphatic system

The lymphatic system is essential for the regulation of tissue pressure, absorption of fats, and immune surveillance.

Lymph nodes are connected to one another by lymphatic vessels that collectively make up the lymphatic system. This system is important for many functions, which include:

- Transport excess interstitial fluid (regulates tissue pressure)

- Absorption of dietary fats (+ fat-soluble vitamins)

- Immune system function

Role in interstitial fluid

Lymph is the fluid that is found within lymphatic vessels that is milky in colour due to its lipid content. It carries interstitial fluid away from peripheral tissue and transports it back to the systemic circulation. This occurs in the neck at the junction between the jugular and subclavian veins via two ducts (one on the left, one on the right):

- Thoracic duct: drains the lower limbs and left half of the upper body

- Right lymphatic duct: drains the right half of the upper body

Failure to take away the fluid that leaks out from the capillaries into the interstitial space will result in lymphoedema. This refers to the accumulation of protein-rich fluid in peripheral tissue causing swelling in the extremities that can be chronic and disabling.

Role in immune function

The lymphatic system contains many organs important in immune function, which include

- Lymph nodes

- Thymus

- Tonsils

- Spleen

- Peyer’s patches (aggregation of lymphoid tissue in the small intestines)

Immune cells such as antigen-presenting cells and lymphocytes are able to travel within the lymphatic system from the skin and other major organs to regional lymph nodes to help initiate a specific immune response. This ability to navigate through the lymphatic vessels is exploited by cancer cells. As epithelial cancers grow, they breach the confines of the epithelial lining and enter lymphatic vessels spreading to regional lymph nodes.

The initiation of an immune response (e.g. to an infection or an autoimmune reaction) or the spread of cancer cells can lead to enlargement of lymph nodes, which we term lymphadenopathy.

Differential diagnosis

The two major causes of lymphadenopathy are infection and cancer.

There are many different causes of lymphadenopathy. The causes may be grouped based on aetiology or location. In general, localised lymphadenopathy (i.e. restricted to a single region) is usually caused by pathology in a nearby region. For example, submandibular lymphadenopathy may relate to an infection of the head, neck or sinuses and inguinal lymphadenopathy may be caused by a sexually transmitted infection.

The classic causes of lymphadenopathy include:

- Localised infections

- Systemic infections

- Medications

- Solid organ cancer

- Haematological cancer

- Miscellaneous conditions (including many inflammatory disorders)

Localised infections

Lymphadenopathy may be caused by a variety of localised infections (e.g. cellulitis, tonsillitis, pharyngitis, sinusitis, otitis media). These infections may be caused by viruses, bacteria, fungi or other types of pathogens. They typically lead to lymphadenopathy close to the area of infection because of the normal function of the lymph nodes to drain the regional area.

Lymphadenopathy secondary to infection is commonly painful due to the rapid enlargement and stretch of the lymph node capsule that activates pain receptors.

Systemic infections

Systemic infections may lead to more widespread lymphadenopathy that can be located in more than one area. Classic causes of widespread lymphadenopathy include:

- Viral: human immunodeficiency virus (typically during the acute seroconversion illness), Epstein-Barr virus (i.e. glandular fever)

- Bacterial: brucellosis, leptospirosis, typhoid fever, secondary syphilis

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis (may be localised or generalised)

- Fungal: Histoplasmosis, cryptococcosis

- Protozoal: Toxoplasmosis, leishmaniasis

Medications

A variety of medications may cause a ‘serum sickness’ type of illness, which occurs when the immune system reacts to the foreign protein antigens within a drug leading to systemic illness. It is characterised by fever, arthralgia, rash and generalised lymphadenopathy.

Classic drug causes include:

- Allopurinol

- Carbamazepine

- Lamotrigine

- Penicillin

- Phenytoin

- Sulfonamides

Solid organ cancer

As solid cancers grow and breach the surrounding basement membrane they may spread via lymphatics to regional lymph nodes. With deep visceral organs, this may be to visceral lymph nodes that can only be detected on imaging (e.g. retroperitoneal lymph nodes, gastric lymph nodes).

Metastasis to lymph nodes is typically associated with painless lymphadenopathy. There are some very typical locations of lymphadenopathy that correspond to a particular site of disease. For example, a squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck is likely to lead to lymphadenopathy in one of the lymph nodes in the neck. Another example is Virchow’s node which refers to left-sided supraclavicular lymphadenopathy that is concerning for gastric cancer.

Haematological cancer

Cancer involving the blood cells are known as haematological malignancies. To keep it simple, these may be leukaemia (cancer of the blood) or lymphoma (cancer of the lymph nodes).

Lymphoma can be broadly divided into Hodgkin’s lymphoma and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. They are cancers arising from abnormal lymphocytes and classically cause painless, firm lymph nodes found in the neck. They are often associated with ‘B’ symptoms that refer to fever, night sweats and weight loss. Lymphoma typically causes isolated or localised lymphadenopathy.

There are many types of leukaemia depending on the abnormal cell of origin. The major groups include acute myeloid, acute lymphocytic, chronic myeloid and chronic lymphocytic. These are predominantly malignancies of the bone marrow and peripheral blood but some types of leukaemia can cause lymphadenopathy by infiltration of the lymph nodes. This typically leads to more generalised lymphadenopathy with the main example being chronic lymphocytic leukaemia.

Miscellaneous conditions

Generalised lymphadenopathy may be a prominent feature of several rare, systemic, inflammatory disorders. Examples include sarcoidosis, rheumatoid arthritis, Still’s disease and lupus. Other rare conditions may cause a localised form of lymphadenopathy (e.g. Castleman’s disease).

History

It is vital to ask about constitutional symptoms that may indicate underlying cancer or inflammatory disorder.

A patient will often present to medical care after noticing a lump or bump within the neck, axillae, or groin. It is important to use the history to determine the natural history of the lesion thus far and whether any concerning features are present that may point towards a serious underlying cause such as cancer.

Natural history

Ask about the onset of the lump and whether it has changed over time. Remember, lymph nodes within the neck and groin can usually be felt as a soft or rubbery ‘pea-sized’ lump that is non-tender.

Establish whether the lymph node has rapidly grown over weeks or slowly over years. Remember that the patient may have only noticed the lump recently whereas, in reality, it may have been present for many years.

Pain

Pain is an important aspect to distinguish. Classically, a rapidly enlarging lymph node due to infection leads to pain or tenderness due to stretching of the lymph node capsule. Alternatively, malignancies (e.g. lymph node metastasis, lymphoma) classically cause a painless lymphadenopathy

Localised or generalised

Established whether the lymphadenopathy is localised to a particular region (e.g. neck) or more generalised involving multiple peripheral sites.

Infective symptoms

Localised lymphadenopathy is commonly associated with an infection in a similar region. Examples include cellulitis, tonsillitis, or otitis media. Ensure you enquire about any infective symptoms near the region (e.g. sore throat, red skin, earache).

Constitutional symptoms

Lymphadenopathy may be a sign of a serious underlying disease such as systemic infection, inflammatory disease, or cancer. It is important to enquire about features of weight loss, anorexia, fever, fatigue, and night sweats. The combination of fever, night sweats, and weight loss are known as ‘B’ symptoms, which are a classic feature of lymphoma.

Risk factors

Generalised lymphadenopathy may be seen in a range of infectious diseases. It is important to ask about risk factors for these diseases including unprotected sexual intercourse or injecting drugs (e.g. HIV), foreign travel and consumption of unpasteurised camel’s milk (e.g. brucellosis), cat scratches (e.g. cat scratch disease), and even tick bites (e.g. Lyme disease).

Examination

It is important to assess all the peripheral lymph node regions and assess for organomegaly.

The identification of peripheral or visceral lymphadenopathy should lead to a search for other involved areas. The peripheral locations where lymph nodes can be identified are divided into the neck and body.

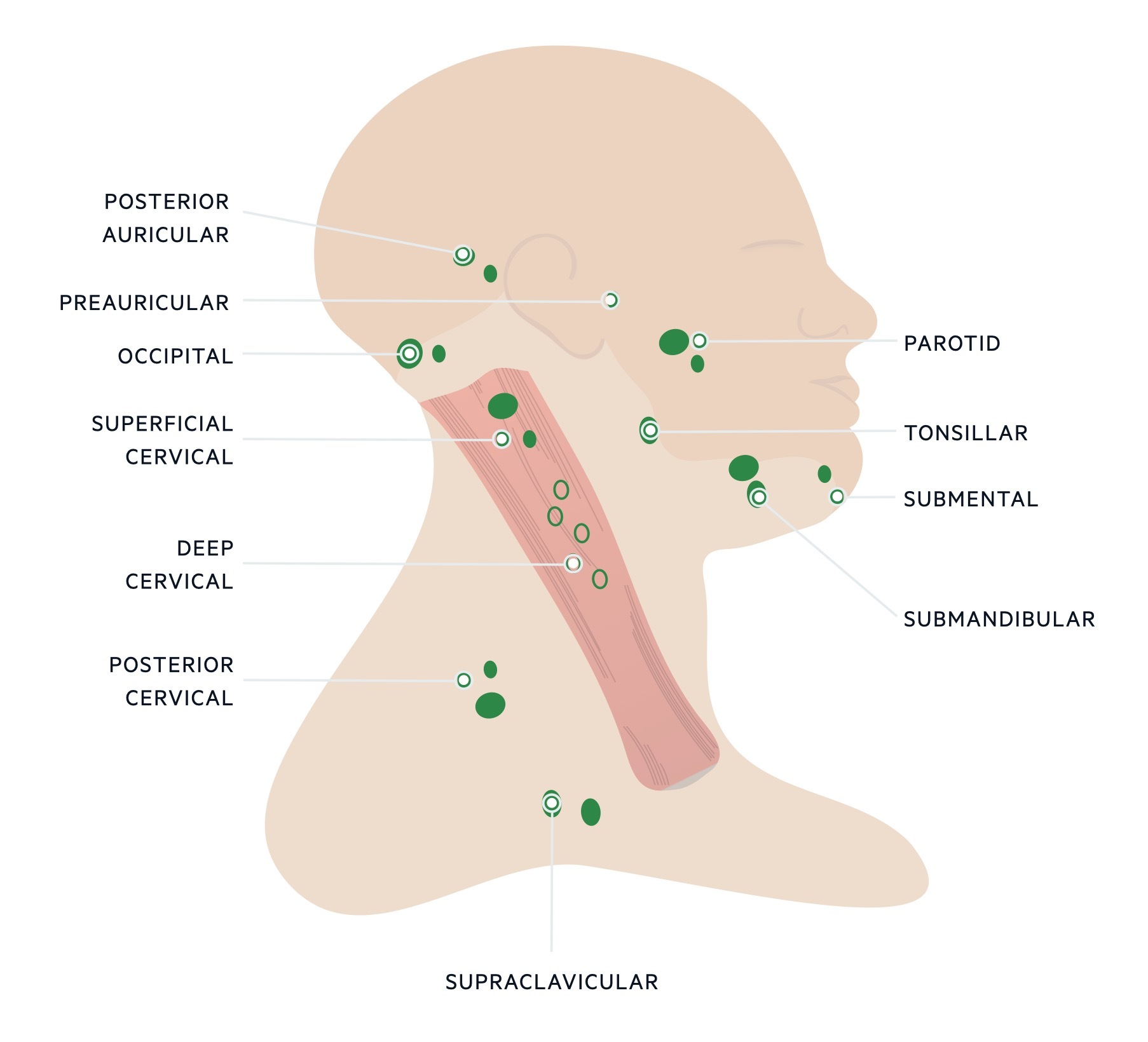

Lymph node locations neck

It is important to palpate all the lymph node stations when examining the neck.

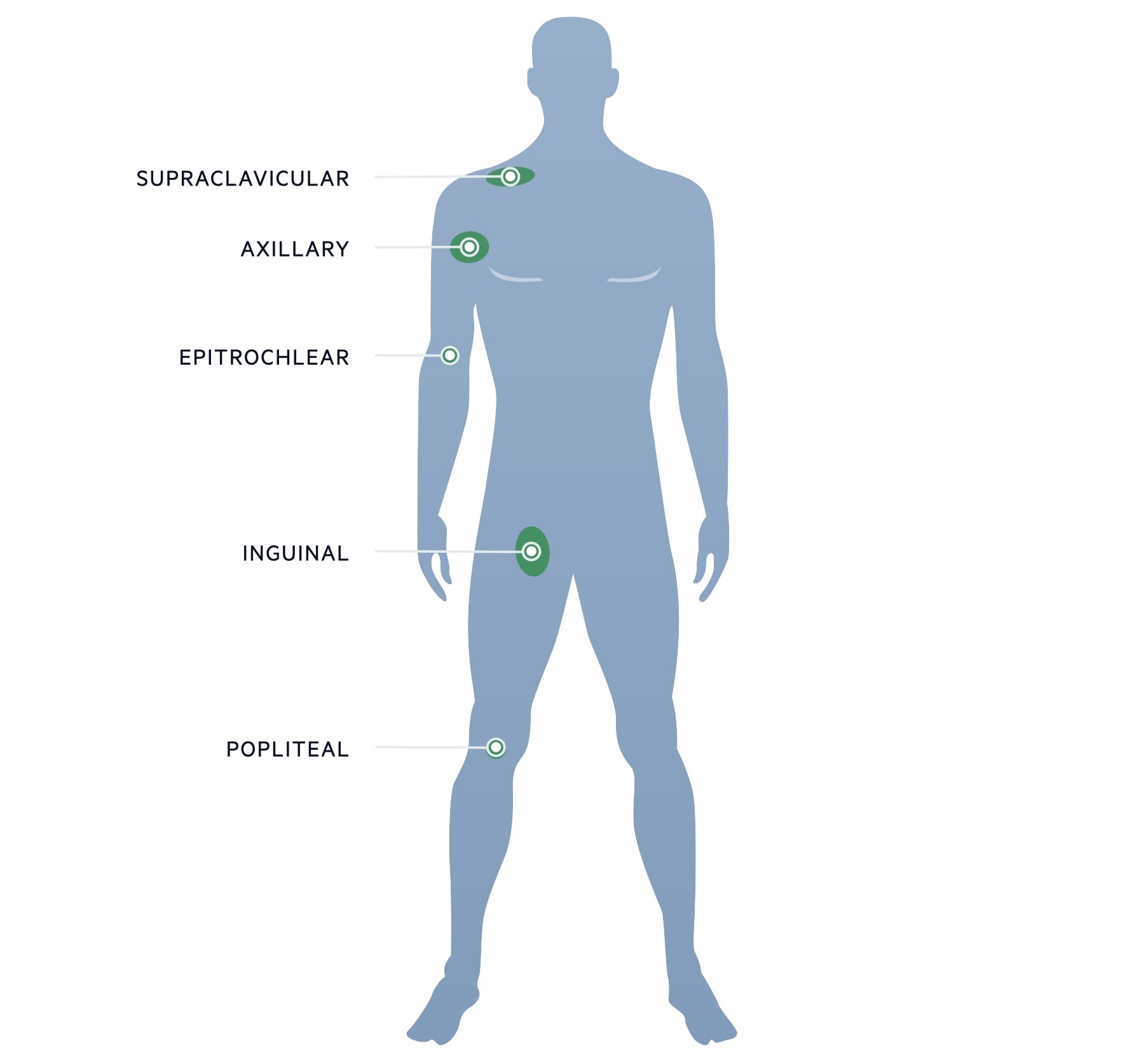

Lymph node locations body

Make sure you adequately assess the peripheral lymph node locations on the body and consider a chaperone when assessing the lymph nodes in the groin.

Lymph node examination

Examination of a lymph node should involve assessment of several key features:

- Size: lymph nodes >1 cm are generally considered abnormal

- Consistency: lymph nodes may be soft, rubbery, or hard. Hard or craggy lymph nodes are commonly found in cancer. Chronic leukaemia may cause multiple soft but firm nodes

- Fixation: lymph nodes should be freely moveable within the subcutaneous tissue. Lymph nodes affected by cancer or inflammation may become fixed to underlying structures or grouped together that we term ‘matted’

- Tenderness: acute inflammatory processes tend to cause pain or tenderness. Chronic cancer-related lymph nodes tend to be painless or non-tender

Other examination findings

Look for signs of an underlying systemic disease and thoroughly exam any areas of suspected infection (e.g. throat and tonsils in suspected tonsillitis). Complete an abdominal examination for hepatosplenomegaly and look for any bruising or petechiae that may indicate a problem with the bone marrow.

Investigations

Imaging enables a more accurate assessment of lymph node size and location.

When a lymph node is felt to be abnormal investigations form an important part of the work-up. Lymph nodes are commonly imagined and/or biopsied.

- Imaging: allows accurate assessment of lymph node size and location. It enables assessment of other lymph node regions including visceral lymph nodes to see whether it is a widespread problem. Imaging also enables visualisation of adjacent structures that are needed to assess for cancer. Cross-sectional imaging (e.g. CT) is usually first-line. CT-PET is also commonly used

- Histology: when a lymph node is considered abnormal it is commonly biopsied to determine the cause. It may be completed using fine-needle aspiration, image-guided biopsy or open biopsy depending on the size, location and suspected aetiology

Additional investigations are needed to determine whether there is an underlying systemic problem. These may include:

- Full blood count: important to assess for any features of malignancy (e.g. anaemia). Abnormally low or high counts may indicate a problem with the bone marrow (e.g. leukaemia)

- Peripheral blood film: allows assessment of any blood abnormalities that may be due to a haematological malignancy

- C-reactive protein: typically raised in infections or inflammation

- Blood cultures: if infection suspected

- Microbiological tests (e.g. swabs, cultures): if an infection is suspected

- Serology: often required for rare infectious diseases. Assesses the immune response to an infection by measuring specific antibodies

- Others: many other tests may be requested depending on the suspected aetiology

Diagnostic work-up

In general, if there is an obvious cause of lymphadenopathy this should be diagnosed and treated. If the cause of lymphadenopathy is suspected to be cancer then the patient requires imaging (e.g. CT scan) and biopsy of the lymph node.

In unexplained localised lymphadenopathy, investigations depend on the age of the patient and suspected aetiology. If the lymph node does not resolve within four weeks then a biopsy is usually recommended.

In unexplained generalised lymphadenopathy, patients should be worked up for a systemic disorder and/or cancer and a biopsy is usually recommended of the most abnormal or accessible node.

Key tip

Always ask about ‘B’ symptoms in patients presenting with lymphadenopathy.

Many causes of lymphadenopathy may be due to a localised infection. It is important to always enquire about ‘B’ symptoms that may indicate an underlying haematological malignancy that requires further investigation. Make sure when faced with lymphadenopathy you perform a full examination from head to toe checking all the peripheral lymph node locations.