Introduction

Caesarean section is an operation in which a baby is delivered via an abdominal incision.

The caesarean section, or procedures similar to it, have been described for thousands of years in many of the world’s cultures. To this day the origins of the term caesarean are disputed.

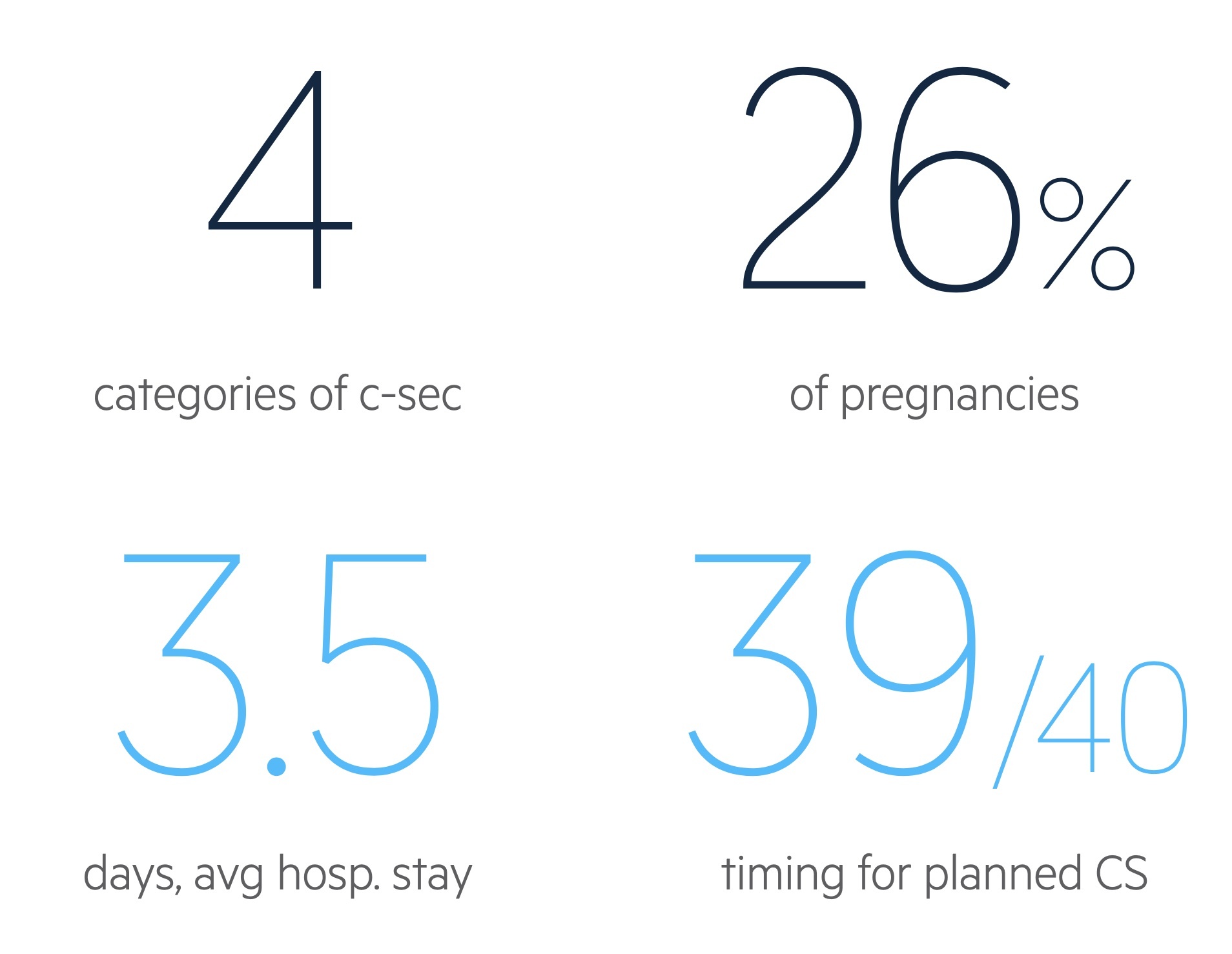

A caesarean section is a birthing option that in some circumstances reduces risk to the mother, baby or both. Many women also choose to opt for a caesarean section for personal reasons having weighed it up against a vaginal delivery. In total, around 25-30% of births in the UK are via caesarean section.

The following NICE guidelines may be of interest:

- NICE Clinical guideline NG 192: Caesarean birth

- NICE guideline NG137: Twin and triplet pregnancy

Elective indications

There are many medical and personal indications for elective caesarean section.

Medical indications

- Breech presentation: external cephalic version (ECV) may be offered first in cases without complication or contraindication (e.g. uterine scar / abnormality, foetal compromise, ruptured membranes, vaginal bleeding). In patients where ECV fails or is not appropriate offer elective caesarean section (USS should be arranged just before the caesarean section).

- Multiple pregnancy: vaginal birth may be safe in uncomplicated dichorionic diamniotic or monochorionic diamniotic twin pregnancy. Other cases are generally offered caesarean section. See NICE guidance for Twin and Triplet pregnancies for more information.

- Transmission of bloodborne viruses: in patients with HIV the benefits and risks of each option should be discussed and the opinion of a specialist sought. HIV and hepatitis C co-infection is an indication for elective caesarean section though hepatitis C alone is not. In hepatitis B, vaccination and immunoglobulin may be given to the baby, in this situation elective caesarean section is not advised.

- Placenta praevia

- Morbidly adherent placenta

Maternal request

Many women have personal reasons to prefer a caesarean section to vaginal delivery. NICE advise a discussion around the reasons for the request, ensuring adequate information is given and questions answered. This should include the risks and benefits of a caesarean section compared to vaginal birth.

If following such a discussion (and the provision of any appropriate support) the patient requests a caesarean section, a planned procedure should be offered.

Emergency indications

The decision to conduct an emergency caesarean section should be made by a senior obstetrician.

Clear communication with the mother and family is essential as is with all members of the MDT to ensure a timely and safe birth. Indications include:

- Cord prolapse

- Antepartum haemorrhage

- Foetal distress

- Failure to progress

Categories

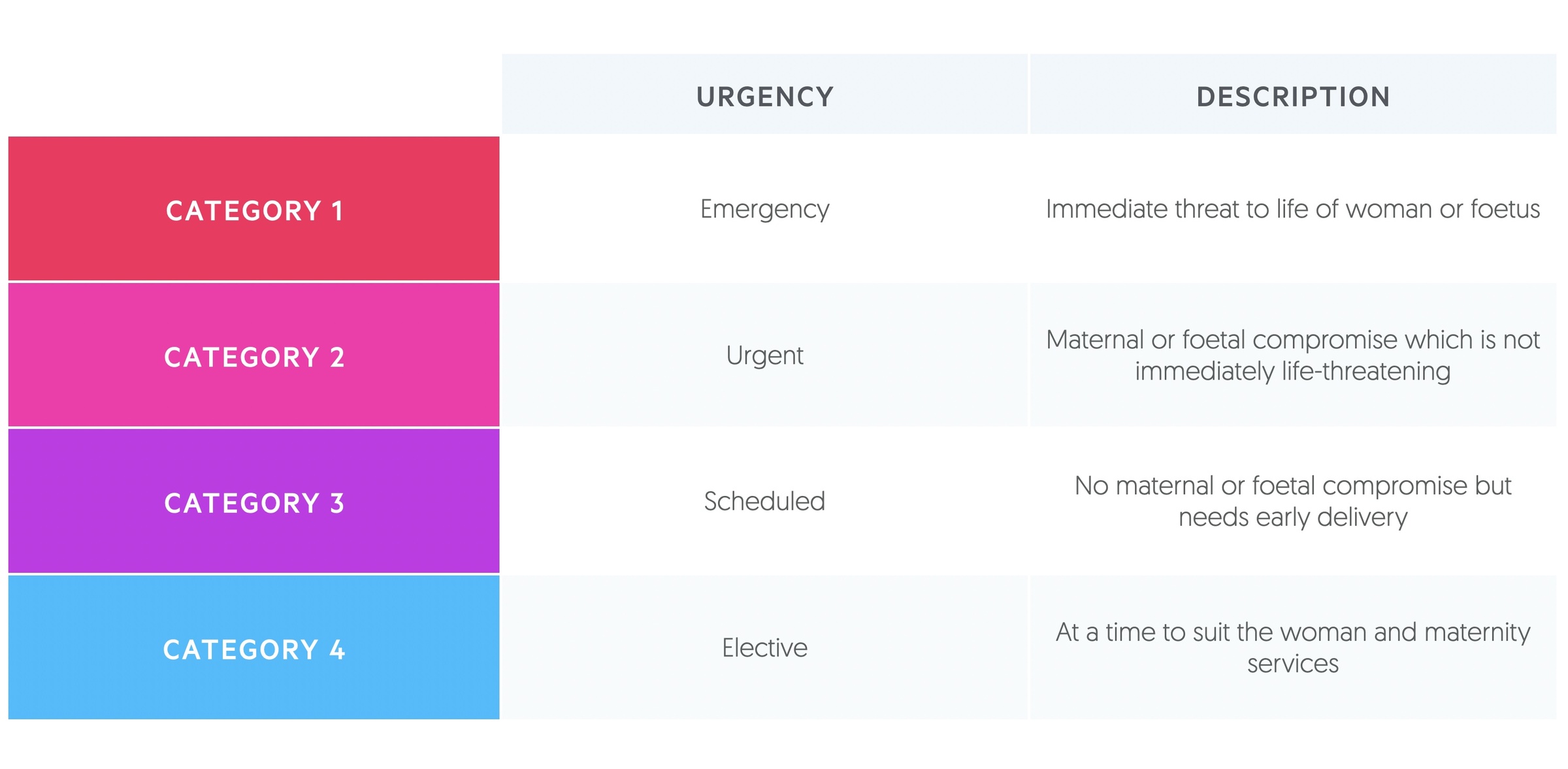

The category of caesarean section allows for a universal classification that communicates urgency and facilitates audit.

Categories 1 and 2 describe unplanned (or emergency) caesarean sections. For a category 1 section a decision to delivery interval (DDI) of 30 minutes is targeted. A DDI of 75 minutes is targeted for category 2 sections (note these are overall obstetric unit audit targets and not necessarily appropriate for every individual case).

Operation

A caesarean section requires excellent teamwork between obstetricians, anaesthetics, midwives, theatre nurses and neonatologists.

Pre-operative considerations

Blood tests: all patients require a full blood count to identify anaemia pre-operatively. Haemorrhage is a complication of caesarean section with blood loss > 1000ml occurring in around 4-8% of cases. According to NICE, patients who are otherwise well do not require group and saves or clotting screens pre-operatively.

Urinary catheter: a urinary catheter should be placed, particularly in patients undergoing regional anaesthesia.

Anaesthesia

Regional anaesthesia is the preferred method. It has been found to be safer for both mother and baby when compared to general anaesthesia.

Some patients require general anaesthesia. Clinicians have to be aware of the risk of failed intubation and aspiration pneumonitis. PPIs / H2 receptor antagonists should be offered prior to GA to reduce the risk of aspiration pneumonitis.

NOTE: You may hear doctors refer to Mendelson Syndrome – it is an eponymous name for chemical pneumonitis secondary to aspiration of stomach contents during general anaesthesia. It is more common in pregnant women.

Procedure

Prophylactic antibiotics are given prior to knife to skin. The operating table should be placed at a 15-degree left tilt to reduce the risk of maternal hypotension.

There are a number of surgical approaches. A NICE document details these and the confusion that sometimes results, in short:

- Transverse incision: defined by NICE as a ‘straight skin incision, 3 cm above the symphysis pubis; subsequent tissue layers are opened bluntly and, if necessary, extended with scissors and not a knife’. This is the preferred approach, it is thought to reduce operating times and post-operative febrile morbidity.

- Pfannenstiel incision: a curved transverse incision is made in the skin crease about 2-3cm above the pubic symphysis. Tissue layers are then opened bluntly.

Following delivery of the baby, the placenta is removed with controlled cord traction.

Complications

Patients must understand the operation, its justification, alternatives and the potential complications that may occur.

Complications should be explained to the patient pre-operatively (unless this is not possible). This includes the small but real risk of emergency hysterectomy as well as the need for blood transfusion. Injury to the bladder and ureters should be explained and that further management may be needed if they occur.

Serious maternal risks include:

- Need for emergency hysterectomy (uncommon, around 7-8/1000)

- Need for further surgery e.g. curettage (uncommon, around 5/1000)

- Venous thromboembolism (rare, around 4-16/1000)

- Bladder / ureteric injury (uncommon, bladder injury around 1/1000, ureteric 3/1000)

- Death (very rare, around 1/12000)

Frequent maternal risks include:

- Abdominal/wound discomfort in the months following surgery

- Risk of further caesarean section being needed during subsequent attempts at vaginal delivery

- Infection

- Haemorrhage

- Need for hospital readmission

Maternal risks in future pregnancies include:

- Increased risk of uterine rupture in future pregnancies

- Increased risk of antepartum stillbirth

- Risk of placenta praevia and placenta accreta in future pregnancies increased

Foetal risks are less common. Lacerations of the foetus affect around 1-2 out of every 100 caesarean sections.

Future pregnancies

The mode of delivery should be discussed in future pregnancies.

The risks and benefits of further caesarean sections and vaginal births should be explained. Maternal wishes must be taken into account.

Women who have had 4 or fewer caesarean sections do not have an increased risk of fever and surgical injuries based upon the ‘planned mode of delivery’. Though the risk of uterine rupture is higher in those with planned vaginal birth, it remains rare.

Those who choose planned vaginal births should have CTG monitoring and receive care at a facility able to handle emergency sections with on-site transfusion services.