Overview

Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic, systemic inflammatory disorder characterised by inflammatory polyarthritis.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is classified as an inflammatory arthropathy because it characteristically affects multiple joints leading to chronic joint pain, swelling and stiffness. However, RA can be a multi-system disorder associated with extra-articular manifestations and systemic features including myalgia, fatigue, low-grade fever, weight loss, and depression.

Patients with RA are often described as seropositive or seronegative depending on the presence or absence antibodies (e.g. Anti-CCP, Rheumatoid factor – discussed below).

Epidemiology

RA is estimated to affect around 1% of the UK population.

The annual incidence of RA is estimated at 40 per 100,000 people. The disease is more common in women (2-4x) and the peak age of onset is between 30-50 years old.

RA is a major cause of long term morbidity. In up to 40%, the disease affects the ability to work within 10 years of diagnosis. In addition, patients with RA have lower physical and mental health quality scores compared to the general population.

Aetiology

The exact cause of RA remains unknown.

RA is likely to occur due to a combination of environmental and immune factors in a genetically predisposed individual. Several genetic and environmental risk factors have been linked with the development of RA.

- Genetics: majority of risk mediated by human leucocyte antigens (e.g. HLA-DR alleles). These are part of the major histocompatibility complex of proteins needed for antigen presentation. Other non-HLA genetic variants and epigenetic changes (i.e. non-germline alterations to genetic code) also contribute.

- Family history: three fold increased risk if first-degree relative affected.

- Demographic risk factors: middle-aged females of North American and Western European ethnicity most at risk.

- Socioeconomic status: lower socioeconomic status and education levels associated with increased risk

- Lifestyle factors: smoking is strongest lifestyle factor for development of RA. Relationship is dose-dependent. Evidence of alcohol inconsistent, some suggestion moderate intake decreases risk. Obesity and low physical activity increase risk

- Infections: infectious trigger hypothesis exists. Acute infection may trigger development of RA due to molecular mimicry. Alternatively, could be related to dysbiosis at mucosal sites (i.e. abnormal immune response at sites where the immune system interacts with microorganisms like the gut, teeth or distal airways).

- Occupational exposures: some airborne inhalant exposures increase risk of RA including exposure to silica and chemical fertilisers

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of RA is incompletely understood.

The current theory for the pathophysiology of RA is that exposure to an external trigger (see aetiology) in a genetically predisposed individual leads to an abnormal, autoimmune response, which targets synovial joints resulting in chronic inflammation and joint damage.

Following a suspected triggering event, there is development of self-citrullination. This is the alteration of a positively charged arginine amino acid into the neutral citrulline. The immune system then reacts to these citrullinated proteins, which is characterised by development of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies. Different citrullinated proteins have been identified and these are situated throughout the body. The overall reactivity of autoantibodies to these citrullinated proteins is thought to be influenced by the gene-environment interaction within the individual.

The abnormal immune response to citrullinated proteins then matures, which may lead to a delay between initiation of autoimmunity and presentation of symptoms. This is followed by a targeting stage where multiple components of the innate (e.g. macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells) and adaptive (e.g. T cells, B cells) immune system are activated. This causes infiltration of synovial joints with immune cells and a subsequent pro-inflammatory response. Inflammation of synovial joints causes the classic synovitis seen in RA, which presents with a symmetrical polyarthropathy of the small joints.

At the joint level, the pro-inflammatory response leads to synovial membrane hyperplasia, or ‘thickening’, which subsequently damages cartilage. This destructive synovial hyperplasia is referred to as a ‘pannus’. There is subsequent boney loss, which manifests as localised and periarticular boney erosions. There may also be destruction of surrounding tendons, ligaments and blood vessels. Traditionally, it is thought the pro-inflammatory response with release of cytokines such as TNF-alpha, IL-6, IL-1-beta and IL-17 promote pro-osteoclastogenic effects that promotes bone loss and inhibit bone formation. Collectively, this causes progressive joint destruction.

Clinical features

The hallmark of RA is a symmetrical, polyarthritis of the small joints of the hands and feet.

Any synovial joint may be affected in RA, but it typically affects small joints in the hands and feet.

Symptoms

- Polyarthropathy: multiple joints affected, usually in symmetrical distribution. In order of frequency:

- Metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints

- Wrists joint

- Proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints

- Knee joint

- Metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints

- Other: elbows, shoulders, ankles, hip, temporomandibular joints, atlantoaxial joint, cervical spine

- Joint pain: worse at rest or inactivity

- Joint swelling

- Joint stiffness: typically early morning stiffness lasting > 1 hour

- Constitutional symptoms: myalgia, fatigue, low-grade fever, weight loss, and low mood

Signs

- ‘Boggy’ joint swelling: due to active synovitis, often difficult to palpate joint line

- Pain on palpation of joints

- Reduced range of movement

- Difficulty with fine motor tasks (e.g. picking up coin, buttoning shirt)

- Muscle atrophy: may see ‘guttering’ between extensor tendons in hands due to wasting of the interossei muscles

Classical signs

These refer to a collection of classical deformities that are suggestive of long-standing RA from a combination of both joint and tendon destruction.

Boutonniere deformity: flexion at the PIP joint with hyperextension of the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint

Boutonniere deformity of the hands

Image courtesy of Prashanth NS

Swan-neck deformity: hyperextension at the PIP joint with flexion of the DIP joint

Swan-neck deformity

Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons

Ulnar deviation at MCPs: subluxation of the MCP joints with deviation of the fingers towards the ulnar bone due to dislocation of flexor tendons and disruption of extensor tendons.

Z-deformity at wrist: hyperextension of interphalangeal joint of thumb in association with carpal bone rotation and radial deviation as well as ulnar deviation at MCPs.

Evidence of ulnar deviation and Z-deformity

Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons

Hammer toes: compensatory flexion of the toes due to weakening and subluxation of surrounding tendons.

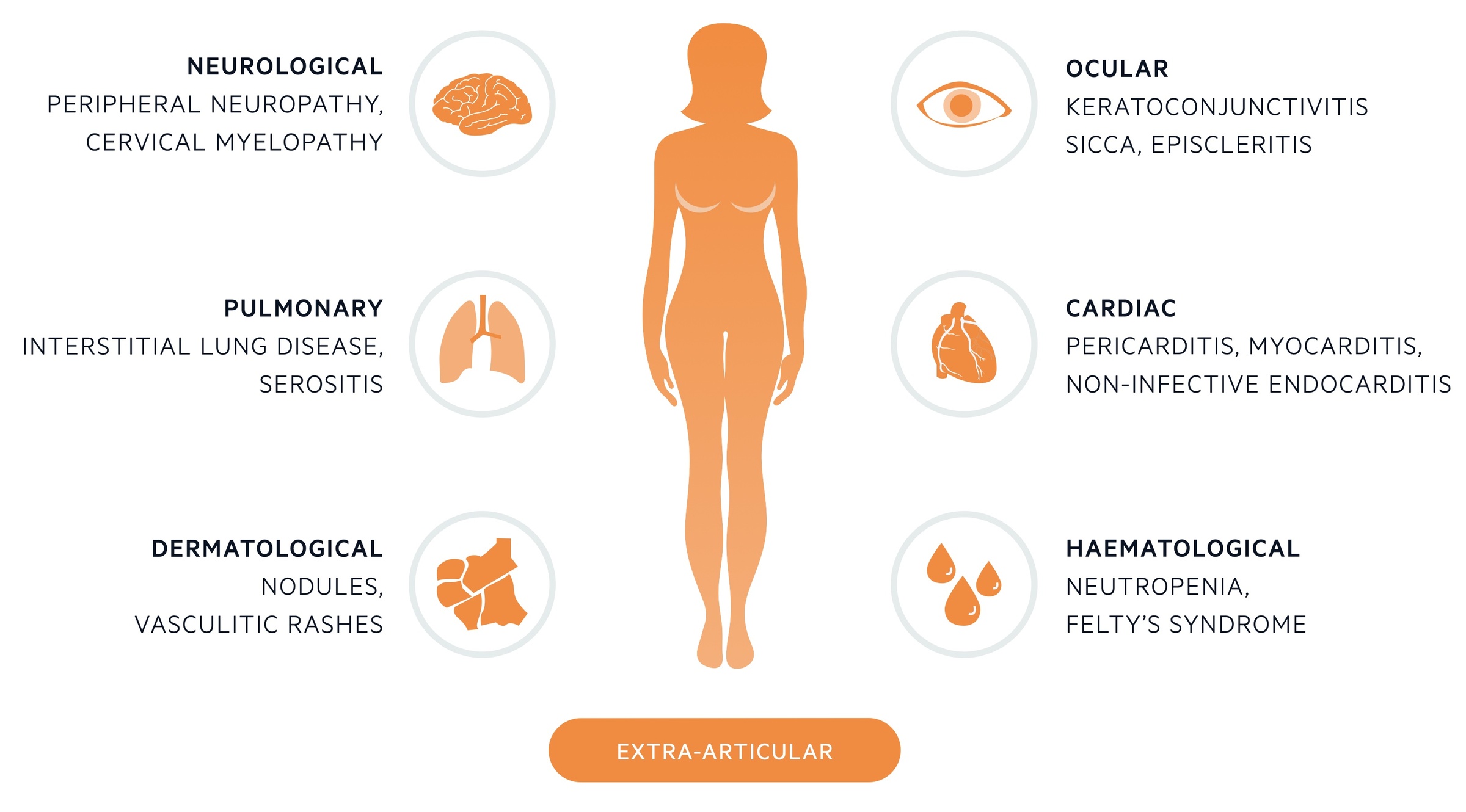

Extra-articular manifestations

These refer to systemic signs and symptoms involving numerous organ systems.

Extra-articular manifestations are systemic clinical manifestations that occur in approximately 40% of patients with RA. They generally reflect long-standing inflammation and more active, severe disease.

They are often caused by active vasculitis (inflammation of blood vessels) within the affected tissue. They are more likely to occur in patients who are seropositive, especially with high titres of autoantibodies.

Ocular

- Keratoconjunctivitis sicca: refers to dry eyes. Seen in 10%. If accompanied with xerostomia (dry mouth) suggestive of secondary Sjögren’s syndrome.

- Episcleritis: inflammation of superficial layer of sclera

- Scleritis: more aggressive inflammation of the whole sclera

Oral

- Xerostoma (dry mouth): If accompanied with keratoconjunctivitis sicca (dry eyes) suggestive of secondary Sjögren’s syndrome.

- Oral ulcers

Pulmonary

- Interstitial lung disease

- Serositis: inflammation of serous membranes (i.e. pleural, pericardium, peritoneum)

- Costochrondritis

Cardiac

- Pericarditis: as part of serositis

- Myocarditis

- Non-infective endocarditis

- Increased risk of ischaemic heart disease

Renal

- Glomerulonephritis (uncommon in the absence of vasculitis)

Neurological

- Peripheral neuropathy: diffuse sensorimotor neuropathy or mononeuritis multiplex

- Entrapment mononeuropathies: carpal tunnel syndrome

- Cervical myelopathy: typically due to cervical spin involvement or atlantoaxial subluxation

Haematological

- Neutropenia: if combined with splenomegaly known as Felty’s syndrome

- Thrombocytopaenia or thrombocytosis

- Haematological malignancies

Dermatological

- Rheumatoid nodules: most present skin complaint (20%). Found on extensor surfaces of upper limb at pressure points (e.g. elbow) as hard nodule. Composed of central fibrinoid necrosis with surrounding fibroblasts. Usually in seropositive patients.

- Vasculitis skin rash: ulcers, digital gangrene, periungual infarcts, splinter haemorrhages

- Pyoderma gangrenosum

Diagnosis

All patients with suspected RA should be referred to a rheumatologist for further assessment.

Referral

Patients with suspected RA due to persistent synovitis based on history and examination should be referred urgently for further assessment.

Persistent synovitis is usually suggested by disease affecting the small joints of the hands or feet or when more than one joint is affected. There is particular emphasis on urgent referral if there is any delay between presentation and symptom onset (e.g. > 3 months).

Investigations (see below) can be requested in primary care, but this should be done to help speed up the diagnostic process in secondary care and should not delay referral.

ACR/EULAR diagnostic criteria

In 2010, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) created a new diagnostic criteria in an attempt to identify patients with RA earlier in the disease process.

This diagnostic criteria is a score based system (out of 10) that looks at four domains:

- Joint involvement (i.e. evidence and location of synovitis, imaging may be used)

- Serology tests (i.e. seropositive or seronegative)

- Acute phase reactants (i.e. markers of inflammation)

- Patient reported symptoms

Score applied when at least one joint has definite synovitis and not better explained by another disease (e.g. gout, lupus).

A definite diagnosis of RA is made when a patient scores 6/10 with the caveat that erosive boney changes classical of RA meets the diagnosis and working through the criteria is unnecessary.

Disease types

The majority of patients have a chronic, persistent form of RA which takes on a relapsing, remitting course with acute flares. In other patients, there may be rapidly progressing joint disease, whereas others may have transient disease without lasting disability.

A small number of patients may have a phenotype called palindromic rheumatism. This refers to inflammatory arthritis with acute episodes of synovitis similar to RA, but between attacks the joints return to normal.

Investigations

Investigations are important as part of the diagnostic criteria and to look for extra-articular manifestations.

Bloods

- Full blood count (FBC)

- Urea & electrolytes (U&E)

- Bone profile, vitamin D

- Liver function tests (LFT)

- Inflammatory markers: C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Normal in 40% of patients

- Autoimmune screen: considered if alternative inflammatory arthritis suspected (e.g. lupus, mixed connective tissue disease)

Rheumatoid factor and anti-CCP

Serological markers of RA. If positive, patients are said to be ‘seropositive’.

- Rheumatoid factor (RF): predominantly an IgM autoantibody that reacts against Fc portion of IgG. Forms immune complexes that contribute to disease process. Seen in 60-70% of patients with RA. May be seen in many other diseases (e.g. lupus)

- Anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP): identified in 80% of patients with RA. Autoantibodies that react to citrullinated proteins. Low sensitivity (~56%) but high specificity (~96%). Positivity predicts erosive disease and worse prognosis.

X-rays

Plain film radiographs should be arranged of the hands and feet looking for boney erosions in all patients. Typical boney erosions aid the diagnosis of RA. X-rays of other sites is dependent on clinical presentation.

Typical features of RA on x-ray includes:

- Soft tissue swelling: may be seen, even on x-ray

- Periarticular osteopaenia (loss of bone density around joints)

- Joint space narrowing

- Boney erosions: typically around bare areas where synovium in direct contact with bone

Ultrasound

Increasingly used in the investigation of early inflammatory arthritis. Allows assessment of joint effusions, visualisation of tendons and changes within the synovial membrane.

Other

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used to look for active joint and soft tissue disease. However, due to cost and availability, usually limited to particular joints (e.g. cervical spine) or where there is diagnostic uncertainty.

Both MRI and ultrasound are superior to clinical examination for detection of early inflammatory arthritis but exact role in RA still being considered.

Management

The goal for treatment of RA is to induce and then maintain disease remission.

There are numerous new pharmacological agents that are available for the treatment of RA. Many have revolutionised treatment, especially in patients with progressive disease that would otherwise lead to permanent disability.

It is important we don’t forget the importance of general care in patients with RA focusing on better access to care, management of co-morbidities and complication, symptom control and specialist therapy input.

General care

All patients should have access to specialist care services including a clinical nurse specialist. This is important for ongoing monitoring and rapid assessment during flares. In addition, will need ongoing drug monitoring for medical therapy.

Patients should be managed holistically with screening for, and management of, any co-morbidities such as hypertension, ischaemic heart disease, osteoporosis and depression. This includes periodic assessment by the wider multidisciplinary team with review of fatigue, pain, effects on daily activities, mobility, ability to work, quality of life, mood and impact on sexual relationships.

Extra-articular manifestations should be screened for and managed by the relevant speciality.

Symptom control

Patients should be offered analgesia to help with pain control. This is commonly NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen or naproxen, but may include newer COX-2 inhibitors (e.g. celecoxib). COX-2 inhibitors have a lower GI side-effect risk profile. In either case, proton pump inhibitor therapy should be considered.

Non-pharmacological methods include access to specialist occupational therapy and physiotherapy, hand exercises programmes and podiatry input.

Pharmacological management

- Initial therapy: offer DMARD first-line (e.g. methotrexate, leflunomide or sulfasalazine). Usually in combination with bridging steroid therapy (2-3 months), which allows time for the DMARD to take effect. Dose escalation as needed.

- Failure to respond: if failed to achieve remission or low disease activity state, escalate to combined DMARD ‘step-up’ therapy. Options include combinations of oral methotrexate, leflunomide, sulfasalazine or hydroxychloroquine.

- Biologic therapy: indications depend on individual biologic. In general, used if there is an inadequate response to DMARD therapy and ongoing active disease. In some cases, may be used second-line in combination with DMARD (e.g. methotrexate) or initial therapy in patients with severely active and progressive disease.

- Managing flares: acute courses of corticosteroids (e.g. prednisolone) may be used to manage a ‘flare’ of recent-onset symptoms or to quickly manage established disease.

- Step-down strategy: consider reducing or stopping therapy in patient who have maintained remission (or low disease activity) for > 1 year without corticosteroids.

Surgical management

Surgery is occasionally needed in patients with RA as an option for pain relief, to improve or prevent further deterioration in joint function or prevent deformity. Options depend on site. Beyond the scope of these notes.

Disease activity

Disease activity scores (DAS) can be assessed in clinic to look at response to treatment and monitor remission. A commonly used score is the DAS28, which involves assessment of 28 joints for swelling and tenderness in combination with inflammatory markers (e.g. CRP/ESR) and global assessment of health scale.

Other measures of disease activity include general examination, global pain scales, health assessment questionnaire (HAQ) that assesses functional ability and imaging (e.g. ultrasound, MRI).

DMARDs

Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) are offered as first-line treatment.

A number of DMARDs can be used in the treatment of RA as stand-alone therapy or in combination.

- Methotrexate: dihydrofolate reductase inhibitor, which interferes with DNA synthesis. Must be given with folic acid. Typically once a week dosing (oral or S/C). Teratogenic and contraindicated in liver disease. Major side-effects include myelosuppression, hepatotoxicity (e.g. fibrosis), pulmonary fibrosis, and increased infection risk.

- Leflunomide: inhibition of pyrimidine synthesis. 10-15% get GI side-effects (diarrhoea and nausea). Teratogenic. Given as daily oral dose. Main side-effects include hepatotoxicity, hypertension, leucopaenia, rash and alopecia.

- Sulfasalazine: mechanism poorly characterised. Anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects. Daily oral dose. Theoretical risk of neonatal haemolysis in third trimester. Classical side-effects include GI, decreased sperm count (whilst taking medication) and cutaneous reactions.

- Hydroxychloroquine: interferes with lysosomal activity and autophagy (destruction of redundant cellular components) and alters intracellular signalling pathways. At cellular levels inhibit immune activation. Avoid in pregnancy, but not necessary to withdraw if well-controlled disease during pregnancy. May precipitate haemolytic crisis in G6PD deficiency. Can cause retinopathy.

Biologics

Biologics are typically given to patients with active RA who have failed to respond to conventional DMARDs.

The number of biologics available and the list of indications is growing rapidly. CKS has a nice summary of the main DMARDs and biologics used in a variety of inflammatory diseases including RA.

In general, biologics can be used an monotherapy, in combination with DMARDs, or as initial therapy in patients with ongoing active RA.

Some more commonly used biologics are listed below:

- Tumour necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors: adalimumab, golimumab, infliximab.

- Rituximab: anti-CD20 antibody. Protein widely expressed on B cells.

- Tocilizumab: anti-IL-6 antibody. Pro-inflammatory cytokine.

Complications

Complications of RA are due to extra-articular manifestations, progressive joint destruction or associated co-morbidities.

Accelerated atherosclerosis, and associated ischaemic heart disease, is the most common cause of death in RA. It is important to assess patients for cardiovascular disease.

There are numerous complications that can develop in RA. These may be due to progressive joint destruction leading to permanent disability or from extra-articular manifestations. In some cases, extra-articular manifestations can cause progressive organ dysfunction (e.g. interstitial lung disease and progressive fibrosis).

Finally, patients are at risk of side-effects related to medications, including steroids, and require routine follow-up and monitoring. In particular, patients are at risk of GI side-effects, increased infections, liver toxicity, osteoporosis and higher risk of malignancy.