Overview

Osteoarthritis is characterised by progressive synovial joint damage resulting in structural changes, pain and reduced function.

It is the most common form of arthritis. Individuals are affected differently, but pain and functional limitation can significantly affect quality of life.

The hands, knees and hips are commonly affected by this condition that leads to cartilage loss and subsequent remodelling of bone. Management includes addressing modifiable risk factors, analgesia and joint replacement surgery.

Epidemiology

It is estimated that 8.75 million people aged 45 or older in the UK have sought treatment for osteoarthritis.

In England, 4.11 million aged 45 or older suffer with knee osteoarthritis, 2.46 million suffer with hip osteoarthritis.

Prevalence is higher in women (particularly disease affecting hands and knees). Women are more likely to require surgery and account for 60% of hip and knee replacements in the UK.

Pathogenesis

Osteoarthritis is a pathology of the entire unit of a synovial joint.

Though traditionally taught as a pathology of articular cartilage, our understanding of osteoarthritis has changed. We are now aware the pathology affects the whole unit of the synovial joint including the synovial fluid and adjacent bone.

In addition, osteoarthritis has normally been referred to as a non-inflammatory arthritis, however we now know inflammatory mediators and processes play a key role in the pathogenesis. It appears inflammatory cytokines interrupt normal repair of cartilage damage.

As cartilage is lost, the joint space narrows, with areas of highest load affected the most. Bone on bone interaction may occur causing large amounts of stress and reactive changes with subchondral sclerosis (via a process called eburnation) seen on x-ray. Cystic degeneration may occur resulting in subchondral cysts.

Risk factors

Osteoarthritis is relatively uncommon before the age of 45, obesity is a significant modifiable risk factor.

- Age

- Female sex

- Raised BMI

- Joint injury

- Joint malalignment and congenital joint dysplasia

- Genetic factors

- Abnormal or excessive stresses (e.g occupation, exercise)

Clinical features

Osteoarthritis is characterised by activity related joint pain. Three common patterns are nodal, knee and hip osteoarthritis.

Nodal OA

The most commonly affected joint is the first carpometacarpal (CMC, base of the thumb). The distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints are often involved. The DIPs are more frequently affected than the PIPs.

Disease is classically described as bilateral and occurring in post-menopausal women.

Progressive disease may result in several characteristic appearances:

- Heberden’s nodes: bony swellings of DIP

- Bouchard’s nodes: bony swellings of PIP

- Fixed flexion deformity of CMC

- Mucoid cysts: painful peri-articular cysts found on dorsum of the finger

Heberden and Bouchard nodes

Image courtesy of Wikipedia Commons

Knee OA

4.11 million people aged over 45 have knee osteoarthritis in England. It is commonly bilateral and often seen with nodal osteoarthritis. Features include:

- Joint pain: Worse with activity, may be worse at night and exacerbated walking downstairs.

- Mechanical locking: Indicating loose body or meniscal tear.

- Giving way

- Joint tenderness

- Joint effusion

Obesity is a significant risk factor, with the medial compartment (normally) far worse affected that the lateral. This can result in a varus deformity becoming apparent. Tricompartmental knee osteoarthritis refers to that affecting the medial, lateral and patella-femoral compartments.

Hip OA

2.46 million people aged over 45 have hip osteoarthritis in England. Classical features include:

- Joint pain: Worse with activity, frequently worse at night.

- Joint tenderness

- Advanced disease: Trendelenburg gait, fixed flexion external rotation deformity.

Investigations

X-ray is the most commonly used imaging modality in the assessment of osteoarthritis.

As noted in the Diagnosis section below, patients who meet the correct criteria can be diagnosed with osteoarthritis without the need for imaging. Imaging tends to be reserved for those with atypical features (e.g. recent trauma, hot swollen joint, rapidly worsening symptoms, prolonged morning stiffness) or an alternative diagnosis is suggested (e.g. inflammatory arthropathy, septic arthritis, malignancy).

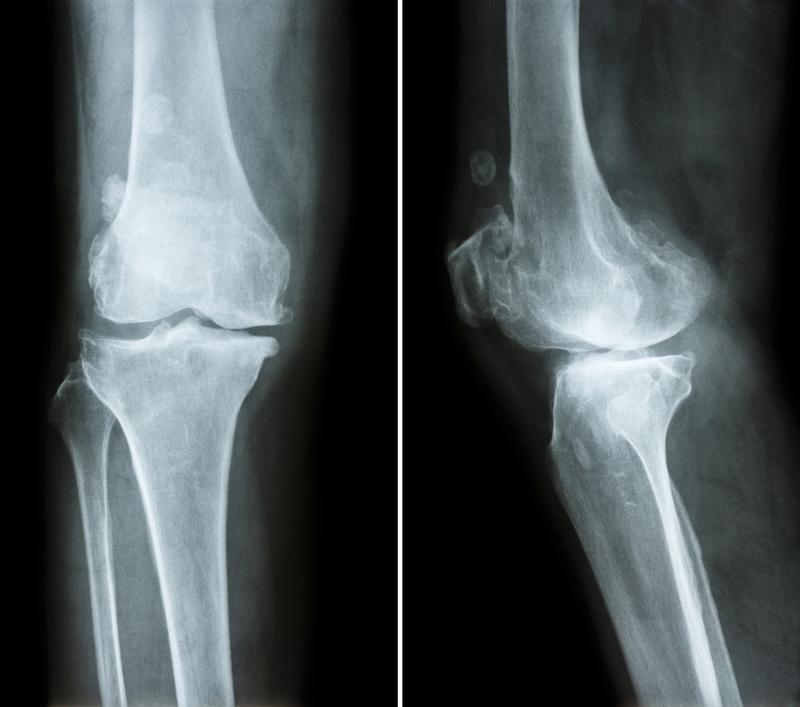

X-ray

Simple, quick and cheap. X-ray will almost always be the first imaging modality obtained if visualisation of the joint is indicated. Classical findings include:

- Joint space narrowing

- Osteophytes

- Subchondral sclerosis

- Subchondral cysts

AP and lateral of knee showing osteoarthritis

However, clinicians must remember that radiographic findings are poorly linked to the patients symptomatic experience. Relatively mild x-ray changes can be experienced as severe and disabling pain.

MRI & CT

Both MRI and CT offer excellent views of the joint. MRI is generally preferred, particularly in the knee when soft tissue injuries of the ACL, PCL, MCL, LCL and menisci are of great interest.

Ultrasound

USS is not typically used in the investigation of osteoarthritis. It may however be used when excluding differentials or to guide interventions (e.g. steroid injection)

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of osteoarthritis is largely clinical based on the presence of characteristic symptoms.

NICE CG 226: Osteoarthritis in over 16s: diagnosis and management (2022) advise a clinical diagnosis (without imaging) can be made when a patient:

- Is 45 or over and

- Has activity-related joint pain and

- Has either no morning joint-related stiffness or morning stiffness that lasts no longer than 30 minutes.

As such, imaging is not considered routine in the diagnosis except where atypical features exist or an alternative diagnosis is suggested (e.g. inflammatory arthropathy, septic arthritis, malignancy).

This of course is not to say osteoarthritis can’t develop before the age of 45. However, as it is less common a higher degree of suspicion is needed to exclude alternative diagnoses and imaging of the joint is likely needed.

Assessment

The assessment of patients with osteoarthritis should be holistic, identifying how the disease affects each individual uniquely.

Everyone is impacted differently by osteoarthritis. To effectively help and manage a patients condition, a full understanding of their disease and its results is needed.

NICE advise discussing the following domains:

- Health beliefs

- Social impact

- Occupational impact

- Effect on mood

- Quality of sleep

- Support network

- Other MSK pain

- Attitudes to exercise

- Influence of co-morbidities

- Pain assessment

Non-pharmacological management

Exercise and appropriate weight loss may result in marked improvement of symptoms.

The diagnosis of osteoarthritis should be explained to the patient, as well as the various management options. Make them aware of support groups/ charities such as Versus Arthritis.

Weight loss

When appropriate patients should be counselled on the benefits of weight loss, on both their symptoms and the progression of their disease.

In general, it has been shown to help improve function, reduce pain and increase quality of life.

Therapeutic Exercise

The goal is to help weight loss (when indicated), increase muscle strength, flexibility and improve aerobic fitness.

For patients with knee and hip osteoarthritis, low impact exercises are often advised. Swimming and static bike cycling are excellent options.

Referral to physiotherapy is the standard – they will be able to explain different exercises that may help with their symptoms and give them a tailored programme to follow.

Manual Therapy

Manual therapy is a physiotherapeutic technique (e.g. joint mobilisation and soft tissue techniques) that may improve joint function and reduce pain for those with hip or knee OA. It should be considered in combination with therapeutic exercise.

Additional

Assessment of foot wear, with advice of appropriate choices should form part of the advice given to a patient. If there are abnormal biomechanics in the lower limb, adjuncts like insoles may be of use.

NICE guidance (NG 226) advise against offering electrotherapy (e.g. transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, TENS) and acupuncture.

Pharmacological management

Paracetamol, topical gels and opioid analgesia may be used to control pain.

Patient may require pharmacological therapy to help manage symptoms, in particular pain. As a general rule, they should be used in conjunction with non-pharmacological therapies and ‘at the lowest effective dose for the shortest possible time’ (NG 226).

Topical, oral and transdermal therapies

Topical NSAIDs are typically first-line, particularly in those with knee OA. Oral NSAIDs may be considered where topical treatment fails or is not appropriate. The risks of long-term (or even short-term) oral NSAIDs are increasingly well understood and are increased in older patients. These include peptic ulcer disease, upper GI bleeding and kidney injury.

If required NSAIDs use should be at the lowest dose appropriate, for the shortest duration needed, with gastroprotection (e.g. a PPI like Omeprazole) offered.

NICE guidance (NG 226) advises against offering glucosamine or strong opioids.

Intra-articular joint injection

Steroid injections may offer marked improvement in symptoms when used as an adjunct to other therapies. The effects are often short lived and in many patients minimal. Risks include septic arthritis (very rare) and avascular necrosis.

NICE guidance (NG 226) advise against hyaluronan injections (due to lack of evidence of efficacy), though some clinicians do use them, typically the patient must buy the medication privately.

Surgical management

In patients whose quality of life is impacted and non-surgical options are ineffective, joint replacement should be considered.

Arthroscopy

Knee arthroscopy is not routinely advised in the management of osteoarthritis. It may be indicated in those with a loose body and mechanical locking.

Joint replacement

Osteoarthritis is the most common indication for primary hip (90%) and knee (98%) replacement. The indication for surgery is typically osteoarthritis substantially impacting the patient’s quality of life that has not responded to conservative measures.

It is a common and safe operation, but all surgery has risks. Short term complications include blood clots (DVT/PE) and infection (surgical site, urinary, chest). Medium to long-term complications include recurrent dislocation (hip replacement), limb length discrepancy, aseptic loosening, blood clots and prosthetic joint infection.

The operations are largely successful at reducing pain and improving mobility. Appropriate post-operative rehabilitation and physio is central to this success. On a survey published by Versus Arthritis after joint replacement 21.1% of knee and 16.6% of hip patients described moderate to severe pain. The figures for those without surgery was 94.6% and 93.9% respectively.