Overview

Bell’s palsy refers to a unilateral facial nerve palsy of unknown cause.

Bell’s palsy, an idiopathic facial nerve palsy, was described by Sir Charles Bell in the 19th century. It is thought to be related to inflammation and oedema of the facial nerve secondary to a viral infection or autoimmunity, but the underlying aetiology remains unclear.

The facial nerve is important for control of the muscles of facial expression. Paralysis of the nerve causes unilateral facial weakness.

Bell’s palsy is relatively uncommon, affecting 20-30 per 100,000 patients per year with an equal sex prevalence.

Click here for our Ramsay Hunt syndrome notes (a differential for patients presenting with facial nerve palsy).

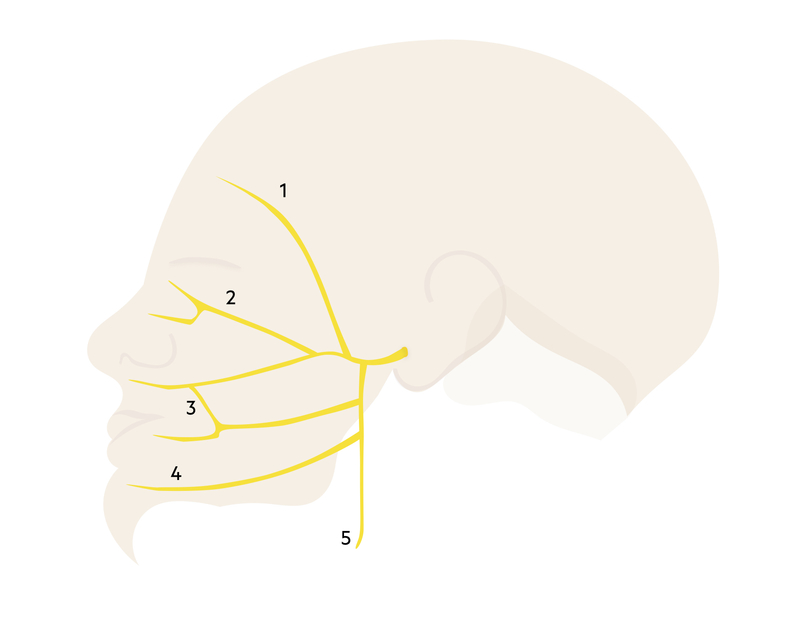

Facial nerve

The facial nerve is divided into five branches, which collectively control the muscles of facial expression.

The facial nerve is the VII cranial nerve. The nucleus is located in the pons, which is part of the brainstem. The nerve root passes through the internal acoustic canal within the temporal bone in close proximity to the inner ear. It then enters the facial canal giving off several branches before exiting the skull via the stylomastoid foramen. It terminates into five terminal motor branches within the parotid gland.

Motor functions

Within the facial canal, the nerve to the stapedius is given off, to supply the stapedius muscle within the inner ear.

NOTE: A common exam question relates to the cause of hyperacusis in Bell’s Palsy. This occurs due to weakness of the stapedius muscle though this particular sign is often absent.

The extracranial portion of the facial nerve contains the main motor root. Prior to reaching the parotid gland, three motor branches are given off:

- Posterior auricular nerve

- Nerve to the posterior belly of the digastric muscle

- Nerve to the stylohyoid muscle

The facial nerve terminates within the parotid gland giving off five terminal motor branches:

- Temporal

- Zygomatic

- Buccal

- Mandibular

- Cervical

Parasympathetic functions

- Greater petrosal nerve: arises in the facial canal. Provides parasympathetic supply to the lacrimal gland via the pterygopalatine ganglion.

- Chorda tympani: arises in the facial canal. Provides parasympathetic supply to the submandibular gland and sublingual glands via the submandibular ganglion.

Special sensory functions

- Chorda tympani: provides taste to the anterior two-thirds of the tongue.

Differential diagnosis

Bell’s palsy is the most common cause of facial nerve palsy.

Other causes of facial weakness (upper and lower motor neuron – see below) include:

- Bell’s palsy

- Inner ear disease (Otitis media, cholesteatoma)

- Parotid disease (Parotid tumour, parotitis)

- Sarcoidosis

- Guillain-Barré syndrome

- Lyme disease

- Trauma

- Stroke

- Tumours

- Encephalitis

- Meningitis

- Multiple sclerosis

- Diabetes mellitus related neuropathy

Clinical features

Bell’s palsy typically presents with rapid onset (< 72 hours) of unilateral facial weakness.

Symptoms

- Unilateral facial weakness

- Post-auricular/ear pain (50%)

- Difficulty chewing

- Incomplete eye closure

- Drooling

- Tingling (cheek/mouth)

- Hyperacusis (heightened sensitivity to sound)

Signs

- Loss of nasolabial fold

- Drooping of the eyebrow

- Drooping of the corner of the mouth

- Asymmetrical smile

- Bell’s sign (upward movement of the eye maintained on attempt to close the eye)

A patient with a right-sided Bell’s Palsy attempting to show his teeth and raise his eyebrows

Image courtesy of James Heilman, MD (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Differentiating upper and lower motor neuron lesions

Bell’s palsy is a ‘stroke mimic’, but it is differentiated from stroke by the absence of ‘forehead sparing’. Facial weakness can be caused by an upper motor neuron (UMN) or lower motor neuron (LMN) lesion. Examples of UMN lesions include stroke and cerebral tumours.

The frontalis muscle, which is supplied by the temporal branch of the facial nerve, has bicortical innervation. This means it receives information from both hemispheres of the cerebral cortex. Therefore, in UMN lesions leading to unilateral facial weakness, there is ‘forehead sparing’ (i.e. the frontalis can still function). In LMN lesions, the frontalis is affected leading to complete unilateral paralysis.

Bilateral involvement

Bilateral facial nerve palsy is an extremely rare condition that is usually secondary to an underlying diagnosis (e.g. Lyme disease, sarcoidosis, Guillain-Barre Syndrome or HIV among others). Therefore, patients presenting with bilateral facial nerve palsy need specialist neurology input.

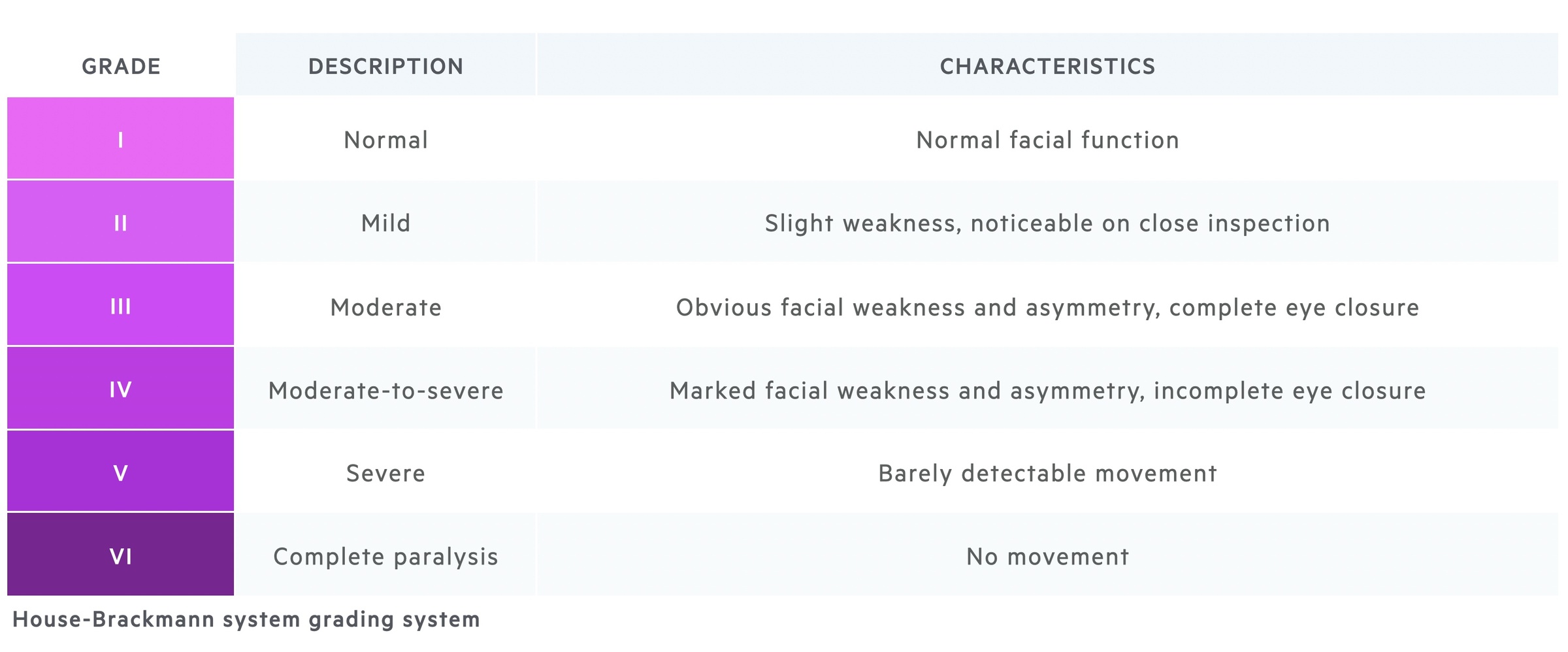

House-Brackmann

Acute facial paralysis can be graded using the House-Brackmann system.

The House-Brackmann system was originally created to assess the degree of facial nerve damage following surgery, but is now commonly used to assess functional recovery following an episode of Bell’s palsy.

Investigations and diagnosis

Bell’s palsy is a clinical diagnosis based on unilateral facial weakness, of rapid onset, without forehead sparing.

Investigations may include routine blood tests, neuroimaging or specialists tests (i.e. lumbar puncture, lyme serology). It is important to consider a HIV test in any patient with Bell’s palsy.

When assessing a patient with new onset facial nerve palsy, it is important to consider alternative causes of facial palsy that may prompt further investigations. Features that point to an alternative diagnosis include:

- Insidious onset +/- progressive

- Overt pain

- Systemic illness +/- fever

- Vestibular abnormalities

- Hearing abnormalities (other than hyperacusis)

- Forehead sparing (i.e. suspected UMN lesion)

- Mass

- Recurrent palsy

- Bilateral involvement

Management

Management is largely supportive, but prednisolone may be used in those presenting within 72 hours of onset.

- General points: Patients should be reassured that the prognosis is good, but it may take several months to recover. If eating is affected advise a straw for liquids and a soft diet.

- Medical therapy: In patients presenting within 72 hours, prednisolone (e.g. 50 mg for 10 days) may be given. Anti-viral treatment (i.e. aciclovir) may be considered in combination with corticosteroids, but this should be discussed with specialists.

- Eye care: It is critical to provide good eye care, which includes drops (i.e. lubricating drops and ointments), advice on taping the eye when sleeping, sunglasses outdoors. Any patient with incomplete eye closure (House-Brackmann ≥ IV) should be referred to ophthalmology.

Complications

The majority of patients with Bell’s palsy will make a full recovery within four months.

Referrals should be made if patients develop eye symptoms (e.g. corneal ulcer), show no improvement after three weeks or develop late problems with aberrant reinnervation (e.g. Marcus-Gunn jaw-winking).

Aberrant reinnervation presents with synkinesis, which describes voluntary muscle contraction leading to involuntary contraction of another muscle. It is due to regenerating collateral nerves that have inadvertently supplied another muscle.